How Does the V8 Engine Execute My Code?

From bytecode to optimized compilation: a look inside V8's execution pipeline

In this post, I want to explore how Google’s V8 engine interprets and executes JavaScript. V8 is written in C++, but since C++ isn’t my primary language and the codebase is massive, I won’t be doing an exhaustive analysis. Instead, I’ll try to cross-reference information available on the web with V8’s actual source code.

What Is the V8 Engine?

The V8 engine is a high-performance JavaScript & WebAssembly engine written in C++, led by Google. It’s also open source, so you can clone it from the V8 engine GitHub repository. It’s currently used in Google Chrome and Node.js, and implements the ECMAScript and WebAssembly standards.

As of June 28, 2019, if you check the Kangax Table, you can see that CH (Chromium) and Node — both powered by V8 — have implemented nearly all ES2016+ features, while Microsoft’s Chakra and Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey still have noticeable gaps marked in red.

To improve compatibility with other platforms and reduce mutual risk, Microsoft Edge will now use the V8 engine as part of this change. We still have a lot to learn, but we’re excited to become part of the V8 community and to contribute to this project.

ChakraCore team ChakraCore Github Issue

As it happens, the Edge browser — which had been using the Chakra engine — has announced it will adopt V8 as part of joining the Chromium open-source project. Whether this is good or bad… I’m not quite sure yet.

If you want to build V8 yourself and actually debug it, you can’t just clone it with git. If you want to go that far, check out the V8 official site’s Checking out the V8 source code.

Chromium is such a massive project that just the installation process for building is quite demanding

Chromium is such a massive project that just the installation process for building is quite demanding

I’ve set it up once before, and as you might expect, it didn’t go smoothly — so I recommend attempting it on a weekend when you have plenty of time. Since I’ll only be analyzing the source code this time, I simply cloned it using git.

How the V8 Engine Works

In general, when using JavaScript, you don’t need to think deeply about low-level details like how the engine works. After all, the whole point of using an engine is so developers don’t have to worry about such things. But if you truly want to squeeze the best possible performance out of JavaScript, you need at least some understanding of how your code is executed.

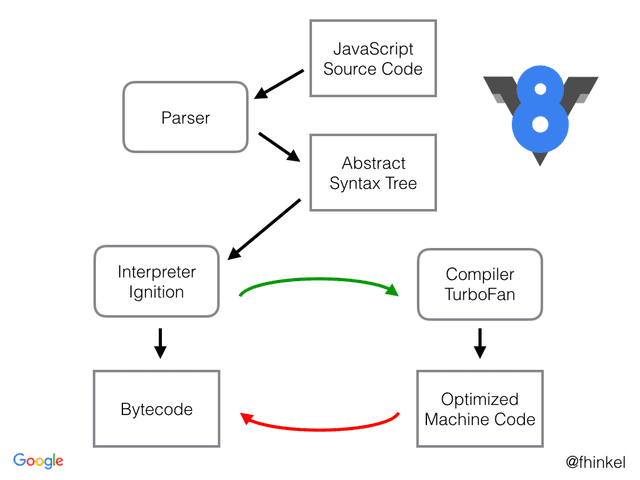

Let’s start with a simple diagram showing how V8 interprets and executes our JavaScript source code. I’ll explain the details below, so for now, just get a general feel for the flow.

Slides from Franziska Hinkelmann's presentation at JSConf EU 2017

Slides from Franziska Hinkelmann's presentation at JSConf EU 2017

V8 takes our source code and first hands it to the Parser. The parser analyzes the source code and transforms it into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree).

Next, this AST is passed to Ignition, which is an interpreter that converts JavaScript into bytecode. By converting the original source into bytecode — a form much easier for the computer to interpret — V8 avoids the overhead of re-parsing the original code, reduces the amount of code, and saves memory during execution.

The bytecode is then executed, making our source code actually run. Among the executed code, frequently used portions are sent to TurboFan, where they’re recompiled into Optimized Machine Code. If that code later becomes less frequently used, it gets deoptimized.

An interesting detail is that many of V8’s components are named after real engine parts. The V8 engine is actually a type of engine commonly found in high-performance cars — named because eight pistons are arranged in a V shape, driving a single crankshaft.

Ignition refers to the igniter used to start an engine. Your source code is revving up and running. And when it gets called too many times and your code starts running hot, TurboFan optimizes it — cooling things down so it doesn’t overheat.

If you’ve read other V8 analysis posts, you may have also seen components called Full-codegen and Crankshaft. The name Crankshaft also comes from real engines — it’s the core component connected to the pistons that converts their reciprocating motion into rotational motion. But as of June 19, 2019, these components can no longer be found in V8.

Starting with V8 v5.9, Ignition and TurboFan are used across the board for JavaScript execution. Additionally, starting with V8 v5.9, Full-codegen and Crankshaft — technologies that have served V8 well — are no longer used in V8, as they were unable to keep up with new JavaScript features and the optimizations those features demand. We plan to remove them entirely soon, which means V8 will have a much simpler and more maintainable architecture going forward.

V8 team Launching Ignition and TurboFan

Yep. They were replaced starting from V8 v5.9.

Yep. They were replaced starting from V8 v5.9.

Before v5.9, Full-codegen and Crankshaft coexisted alongside the newer components — but this wasn’t by choice. Early versions of Ignition and TurboFan didn’t perform as well as expected, and there were issues where optimized code couldn’t be directly deoptimized back to bytecode, so the V8 team had no choice but to keep Full-codegen and Crankshaft around as fallbacks.

The V8 team’s original goal was always to use only Ignition and TurboFan, freely moving between bytecode ↔ optimized code.

This video is from BlinkOn 2016, where Ross McIlroy of the Chrome Mobile Performance London Team introduces Ignition. The 9:47–11:14 segment explains the unfortunate reasons they couldn’t remove the legacy Full-codegen and Crankshaft. He seems to find it funny himself while explaining.

Now let’s take a brief look at how V8 actually parses and executes JavaScript.

Parsing: Understanding What the Code Means

Parsing is the process of loading source code and transforming it into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree). The AST is a data structure widely used in compilers — think of it as restructuring the source code we write into a form that’s easy for the computer to understand.

For example, if we were to parse JavaScript with JavaScript, it would look something like this:

function hello (name) {

return 'Hello,' + name;

}

// The code above can be roughly structured like this:

{

type: 'FunctionDeclaration',

name: 'hello'

arguments: [

{

type: 'Variable',

name: 'name'

}

]

// ...

}Laid out like this, it’s simpler than you might expect. But this is just one example — the parser also has to interpret and parse syntax like for, if, a = 1 + 2, function () {}, and so on. That’s why the parser’s internals are surprisingly large. V8’s parser.cc file alone exceeds 3,000 lines.

In any case, just remember that parsing is the process of converting code into an AST — a form that’s easy for the computer to analyze. The V8 engine does exactly what we just illustrated in JavaScript, but using C++.

Let’s take a look at the method in V8’s parsing code that handles literal arithmetic expressions like 1 + 2.

// v8/src/parsing/parser.cc

bool Parser::ShortcutNumericLiteralBinaryExpression(Expression** x, Expression* y, Token::Value op, int pos) {

if ((*x)->IsNumberLiteral() && y->IsNumberLiteral()) {

double x_val = (*x)->AsLiteral()->AsNumber();

double y_val = y->AsLiteral()->AsNumber();

switch (op) {

case Token::ADD:

*x = factory()->NewNumberLiteral(x_val + y_val, pos);

return true;

case Token::SUB:

*x = factory()->NewNumberLiteral(x_val - y_val, pos);

return true;

// ...

default:

break;

}

}

return false;

}This is a static method called ShortcutNumericLiteralBinaryExpression (what a mouthful…) on the Parser class, declared in V8’s parser.cc.

Looking at the parameters: x and y are Expression objects representing the values used in the expression. op represents the actual operation — whether the expression means x + y or x - y — along with its type. pos indicates the position of the code currently being parsed within the overall source.

As explained above, this method is called when it encounters source code like 1 + 2. You can see it inspecting the expression against conditions like Token::ADD and Token::SUB and parsing accordingly. The “tokens” here are string fragments produced by lexically analyzing the source code according to JavaScript’s grammar rules.

// Tokens look roughly like this

['const', 'a', '=', '1', '+', '2'];After the calculation, the resulting value is turned into an AST node using the AstNodeFactory class’s NewNumberLiteral static method.

// v8/src/ast/ast.cc

Literal* AstNodeFactory::NewNumberLiteral(double number, int pos) {

int int_value;

if (DoubleToSmiInteger(number, &int_value)) {

return NewSmiLiteral(int_value, pos);

}

return new (zone_) Literal(number, pos);

}During this process, V8 identifies the meaning of code elements like variables, functions, and conditionals. JavaScript’s scoping — something we’re all familiar with — is also established during this phase. For more details on variable declarations, see JavaScript’s let and const, and TDZ.

Generating Bytecode with Ignition

Bytecode is an intermediate representation produced by compiling high-level source code into a form that a virtual machine can understand more easily. In V8, Ignition is responsible for this.

What Is Ignition?

Ignition is an interpreter that completely replaces the legacy Full-codegen. The old Full-codegen compiled the entire source code at once. As mentioned earlier, the V8 team recognized that Full-codegen’s approach of compiling all source code at once consumed a significant amount of memory.

Additionally, since JavaScript is a dynamically typed language — unlike statically typed languages like C++ — there were too many unknowns before runtime, making optimization with this approach extremely difficult.

So when developing Ignition, they opted for an interpreter-based approach that processes code line by line as it executes, rather than compiling everything at once, aiming for three key benefits:

- Reduced memory usage. Compiling JavaScript to bytecode is more efficient than compiling directly to machine code.

- Reduced parsing overhead. Bytecode is concise, making it easier to re-parse.

- Reduced compilation pipeline complexity. Both optimization and deoptimization only need to deal with bytecode, simplifying everything.

Ross McIlroy Ignition - an interpreter for V8

Just remember that Ignition is the component that converts code to bytecode line by line as it executes.

So what does bytecode actually look like, and why is it easier for the computer to interpret? Let’s take the hello function from earlier and see what bytecode it generates.

Viewing the Bytecode Yourself

function hello(name) {

return 'Hello,' + name;

}

// If the code isn't used, it won't be interpreted to bytecode, so we need to call it.

console.log(hello('Evan'));If you’re using Node.js v8.3+, you can add the --print-bytecode flag to see how your source code was interpreted into bytecode. Alternatively, you could use V8’s D8 debugging tool, but that requires building V8 — and as I mentioned, the build setup isn’t exactly smooth. So I just used --print-bytecode.

$ node --print-bytecode add.js

...

[generated bytecode for function: hello]

Parameter count 2

Frame size 8

15 E> 0x2ac4000d47b2 @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

30 S> 0x2ac4000d47b3 @ 1 : 12 00 LdaConstant [0]

0x2ac4000d47b5 @ 3 : 26 fb Star r0

0x2ac4000d47b7 @ 5 : 25 02 Ldar a0

46 E> 0x2ac4000d47b9 @ 7 : 32 fb 00 Add r0, [0]

53 S> 0x2ac4000d47bc @ 10 : a4 Return

...This is what the hello function looks like after being converted to bytecode. Wait — I only used one parameter, name, but the Parameter count says 2.

One of them is the implicit receiver, this. If you use this inside a function to refer to the function itself — yes, it’s that this. Below that, you can see values being assigned to registers. Let me explain briefly.

For those who might not be familiar: a register is high-speed memory built into the CPU, and an accumulator is a register used to store intermediate calculation results.

StackCheck: Checks the upper limit of the stack pointer. If the stack exceeds the threshold, a Stack Overflow occurs and function execution is halted.LdaConstant [0]:Ldstands forLoad. It loads a constant into the accumulator. This constant isHello,.Star r0: Moves the value in the accumulator to registerr0.r0is a register for local variables.Ldar a0: Loads the value from registera0into the accumulator. In this case,a0holds the argumentname.Add r0, [0]: AddsHello,fromr0and0, storing the result in the accumulator. The constant0is mapped to the argumentnameat runtime.Return: Returns the value in the accumulator.

The hello function is something you’d declare without a second thought when writing JavaScript, but internally it goes through 6 steps to return a value.

It does this much work under the hood, so let's not complain too much when it's occasionally slow

It does this much work under the hood, so let's not complain too much when it's occasionally slow

Bytecode is essentially a set of instructions telling the CPU exactly how to use its registers and accumulator. It’s mind-bending for humans, but much easier for the computer to understand.

Since the V8 engine converts all of our JavaScript code into bytecode like this internally, the first time a line of code runs there’s a slight delay — but from then on, it can achieve performance close to a compiled language.

Cooling Down Hot Code with TurboFan

TurboFan is the optimizing compiler that completely replaced the legacy Crankshaft starting with V8 v5.9. So why did Crankshaft get retired?

Since V8 first came into the world, new computer architectures emerged and JavaScript continued to evolve, so V8 had to keep up. The V8 team kept patching things to accommodate new specifications, but eventually they determined that Crankshaft’s architecture couldn’t sustain continued expansion. So they built TurboFan — designed with multiple layers for more flexible extensibility.

Running Crankshaft and TurboFan simultaneously probably felt something like this...

Running Crankshaft and TurboFan simultaneously probably felt something like this...

When supporting 7 architectures, what took 13,000–16,000 lines of code in Crankshaft could be covered in under 3,000 lines with TurboFan.

During runtime, V8 has a component called the Profiler that collects data such as how frequently functions and variables are called. When this data is brought to TurboFan, it picks out the code that meets its criteria and optimizes it.

The optimization techniques include Hidden Classes, Inline Caching, and various others, but I’ll cover those in more detail in a future post.

To briefly explain: Hidden Classes involve classifying similar objects together for reuse. Inline Caching means that if a frequently used piece of code is a function call like hello(), it gets replaced with the function’s actual body function hello () { ... }. It’s literally caching.

What Conditions Trigger Optimization?

So what exact conditions does TurboFan use to determine which code to optimize? Let’s look at RuntimeProfiler’s ShouldOptimize method, which determines whether a function should be optimized.

// v8/src/execution/runtime-profiler.cc

OptimizationReason RuntimeProfiler::ShouldOptimize(JSFunction function, BytecodeArray bytecode) {

// int ticks = how many times this function has been called

int ticks = function.feedback_vector().profiler_ticks();

int ticks_for_optimization =

kProfilerTicksBeforeOptimization +

(bytecode.length() / kBytecodeSizeAllowancePerTick);

if (ticks >= ticks_for_optimization) {

// If the call count exceeds the threshold, consider it "hot"

return OptimizationReason::kHotAndStable;

} else if (!any_ic_changed_ && bytecode.length() < kMaxBytecodeSizeForEarlyOpt) {

// If not inline-cached and bytecode length is small, consider it a small function

return OptimizationReason::kSmallFunction;

}

// If none of the above apply, don't optimize

return OptimizationReason::kDoNotOptimize;

}I was a bit surprised by how few conditions there are. Of course, there are more granular conditions handled elsewhere, but this method captures the big picture.

kHotAndStable means the code is hot and stable — in plain terms, it’s called frequently (hot) and doesn’t change (stable). Code inside loops that repeatedly performs the same operation is a prime candidate for this.

kSmallFunction means that based on the length of the interpreted bytecode, if it doesn’t exceed a certain threshold, the function is considered small and gets optimized. Small, simple functions are likely to have very abstract or limited behavior, which makes them stable.

Peeking at TurboFan in Action

Let’s see how optimization works with a simple code example. I’ll declare a small function and call it repeatedly in a loop.

My goal is for the function to hit the ticks >= ticks_for_optimization condition and reach kHotAndStable status. I figure if I declare any function, use the same argument types, and call it rapidly and repeatedly, it should hit ShouldOptimize’s threshold and get optimized as kHotAndStable.

When running Node.js with the --trace-opt flag, you can observe code being optimized at runtime.

function sample(a, b, c) {

const d = c - 100;

return a + d * b;

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

sample(i, 2, 100);

}$ node --trace-opt test.js

[marking 0x010e66b69c09 <JSFunction (sfi = 0x10eacdd4279)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 3/3 (100%), generic ICs: 0/3 (0%)]

[marking 0x010e66b6a001 <JSFunction sample (sfi = 0x10eacdd4371)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 3/3 (100%), generic ICs: 0/3 (0%)]

[compiling method 0x010e66b6a001 <JSFunction sample (sfi = 0x10eacdd4371)> using TurboFan]

[compiling method 0x010e66b69c09 <JSFunction (sfi = 0x10eacdd4279)> using TurboFan OSR]

[optimizing 0x010e66b69c09 <JSFunction (sfi = 0x10eacdd4279)> - took 0.132, 0.453, 0.027 ms]

[optimizing 0x010e66b6a001 <JSFunction sample (sfi = 0x10eacdd4371)> - took 0.850, 0.549, 0.012 ms]

[completed optimizing 0x010e66b6a001 <JSFunction sample (sfi = 0x10eacdd4371)>]It did get optimized. The ICs with typeinfo: 3/3 (100%) tells us inline caching was applied.

But the optimization reason says small function. Since I wanted the kHotAndStable condition, I need to tweak the code and try again. My function was too simple — TurboFan didn’t take it seriously.

function sample() {

if (!arguments) {

throw new Error('Please provide arguments');

}

const array = Array.from(arguments);

return array

.map(el => el * el)

.filter(el => el < 20)

.reverse();

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; ++i) {

sample(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);

}I made it moderately more complex — though the logic itself is meaningless. The sample function simply takes arguments, transforms them, filters them, reverses the order, and returns the result. The optimization targets TurboFan would be watching are functions like sample, map, filter, reverse, and Array.from.

Since there are many targets, the log output is enormous, so I’ll just show the parts where TurboFan marks functions for optimization.

$ node --trace-opt test.js

[marking 0x1a368a90cc51 <JSFunction (sfi = 0x1a36218d4279)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 3/3 (100%), generic ICs: 0/3 (0%)]

[marking 0x1a36bcfa9611 <JSFunction array.map.el (sfi = 0x1a36218d46f9)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 1/1 (100%), generic ICs: 0/1 (0%)]

[marking 0x1a36bcfa96a1 <JSFunction array.map.filter.el (sfi = 0x1a36218d4761)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 1/1 (100%), generic ICs: 0/1 (0%)]

[marking 0x1a368a90cc11 <JSFunction sample (sfi = 0x1a36218d4371)> for optimized recompilation, reason: hot and stable, ICs with typeinfo: 10/11 (90%), generic ICs: 0/11 (0%)]

[marking 0x1a36e4785c01 <JSFunction UseSparseVariant (sfi = 0x1a36660866d9)> for optimized recompilation, reason: small function, ICs with typeinfo: 1/5 (20%), generic ICs: 0/5 (0%)]

[marking 0x1a36e4786fc1 <JSFunction reverse (sfi = 0x1a3666086f21)> for optimized recompilation, reason: hot and stable, ICs with typeinfo: 4/5 (80%), generic ICs: 0/5 (0%)]There it is — reason: hot and stable. Since the output includes the function name in the format <JSFunction function_name>, we can see that sample and reverse were the ones marked for optimization. This shows how TurboFan profiles multiple data points — not just one — to determine whether to optimize a piece of code.

Closing Thoughts

They say that well-written JavaScript can achieve performance approaching C++. When I first heard this, I thought “How can an interpreted language match a compiled language’s performance?” — but after examining V8’s internals, I was surprised by just how many optimization techniques are packed in.

Tearing apart the JavaScript engine piece by piece and deepening my understanding of a language I love was genuinely fun. (I wish I’d used C++ more back in school…)

There are actually many optimization techniques inside V8 that’ll make you go “Whoa, that’s brilliant…” — and I wanted to introduce them all. But as I wrote, the content kept getting longer and started going off on tangents…

So for now, I’ll stop at explaining the overall flow. In the next post, I’ll dive deeper into how Ignition and TurboFan work in more detail.

Understanding TurboFan’s workflow in particular is a shortcut to optimizing your own JavaScript code, so it should come in handy.

This concludes my post: How Does the V8 Engine Execute My Code?

관련 포스팅 보러가기

JavaScript's let, const, and the TDZ

Programming/JavaScript[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes

Programming/JavaScriptBeyond Classes: A Complete Guide to JavaScript Prototypes

Programming/JavaScriptFixing Webpack Watch Memory Leak

Programming/WebHeaps: Finding Min and Max Values Fast

Programming/Algorithm