[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Understanding the Keplerian Elements

A guide to Keplerian orbital elements — no astronomy or math expertise required

![[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Understanding the Keplerian Elements [Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Understanding the Keplerian Elements](/static/746a090a9954b09cea8d75079269697d/2d839/thumbnail.jpg)

In this post, I’ll cover the orbital and position calculations of celestial bodies — the part that gave me the most trouble while developing a solar system simulation. As someone who gave up on math in high school, my goal is to explain things as simply as possible for others who had a similar experience.

There are plenty of resources online about plotting orbits and estimating planetary positions, but understanding them requires familiarity with basic astronomical terminology. Apparently these are terms you learn in a high school earth science class, but since I spent most of high school sleeping, I had to look everything up from scratch.

I’m not an astrophysics graduate — just a developer — so there may be inaccuracies in my explanations.

Before diving into the Keplerian elements themselves, let’s cover the most fundamental terms needed to understand the explanations that follow.

Coordinates and Reference Planes

Celestial bodies move through an infinitely extending three-dimensional space, so a coordinate reference system is essential to describe their motion. This means deciding where to place the center of the coordinates and what to consider 0° when measuring angles.

The Celestial Sphere and the Ecliptic

The celestial sphere is an imaginary sphere of infinite radius centered on the observer.

Here, “the observer” doesn’t mean an actual person but the celestial body where the observer is located. Since humans haven’t yet had occasion to use these concepts from any planet other than Earth, the observer is conventionally Earth. The projection of Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator.

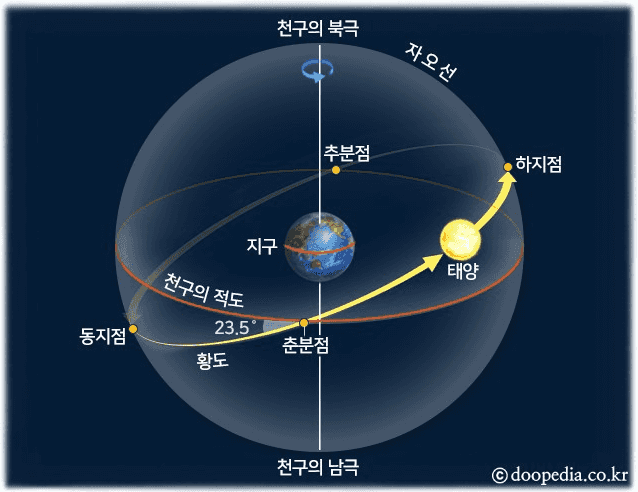

The yellow line labeled ecliptic in the diagram above represents the apparent path the Sun traces across the sky as observed from Earth.

In other words, the concepts of the celestial sphere and ecliptic originate from the geocentric model. They define the positions of celestial objects in the sky relative to Earth as the observer.

Because Earth’s rotational axis is tilted 23.5°, the celestial equator and the ecliptic meet at an angle of 23.5°. Due to this tilt, from Earth’s perspective the Sun appears to orbit Earth while drifting south and then north. The point where the Sun moves from south to north is called the vernal equinox, and the point where it moves from north to south is called the autumnal equinox.

But living in the 21st century, we know that it’s actually Earth orbiting the Sun, not the other way around. So while the diagram above shows Earth standing upright with the Sun orbiting at a tilt, in reality the ecliptic is the reference plane and the celestial equator is the one tilted at 23.5°.

Right Ascension and Declination

The celestial sphere is ultimately a concept for expressing the positions of objects in the sky relative to Earth. The positions of celestial bodies are expressed using right ascension and declination.

This is the same idea as using the geographic coordinate system with longitude and latitude to express a specific location on Earth. In the geographic coordinate system, latitude takes the equator as 0° and the poles as 90° to mark vertical position, while longitude takes the Greenwich Observatory as 0° and divides 180° east and 180° west for horizontal position.

By the same principle, when looking up at the sky from Earth, any object on the celestial sphere can be located with just two values — right ascension and declination.

Right ascension and declination are the longitude and latitude in the equatorial coordinate system, which uses the celestial equator as its baseline. Right ascension measures the counterclockwise angle from the vernal equinox to the target object along the celestial equator. Declination measures the angular distance from the celestial equator to the target object. In short, knowing the celestial equator, the vernal equinox, the right ascension, and the declination is enough to pinpoint any object on the celestial sphere. (Of course, the equatorial coordinate system assumes objects exist on the two-dimensional surface of the celestial sphere, so it doesn’t define the distance to the object.)

An interesting fact is that most celestial bodies — except for solar system objects and comets — barely move on the celestial sphere, so they have essentially fixed right ascension and declination values that make them easy to locate.

Unlike geographic longitude, right ascension in the equatorial coordinate system is expressed in time units like hours and minutes. Since Earth rotates 360° in 24 hours, 1 hour of right ascension corresponds to 15°. Declination takes the celestial equator as 0° and defines the celestial north pole as +90° and south pole as -90°, so it always falls between -90° and +90°.

For reference, the coordinate system centered on a ground-level observer on Earth (rather than the equator), using the observer’s horizon as the reference plane, is called the horizontal coordinate system.

Orbital Terminology

Ascending Node / Descending Node

A celestial body’s orbital plane is generally tilted relative to a reference plane. The reference plane can vary by definition, but for the solar system it refers to the ecliptic.

Earlier, I explained that in the equatorial coordinate system, the point where the Sun moves from south to north is the vernal equinox, and where it moves from north to south is the autumnal equinox.

Similarly, for any body orbiting a central object, the point where it crosses from south to north of the reference plane is called the ascending node, and the point where it crosses from north to south is the descending node. While “vernal equinox” and “autumnal equinox” are terms specific to us living on Earth, “ascending node” and “descending node” are universal terms applicable to any body orbiting along a specific trajectory.

In the solar system, since the central body is the Sun, the ecliptic is used as the reference.

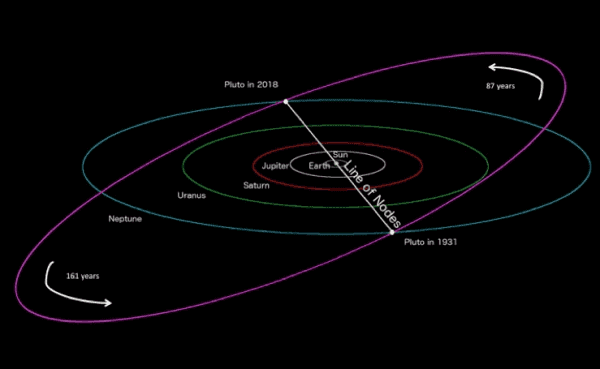

Looking at Pluto's orbit, it's easy to see what it means to rise north or descend south of the ecliptic relative to the Sun.

Looking at Pluto's orbit, it's easy to see what it means to rise north or descend south of the ecliptic relative to the Sun.

Aphelion / Perihelion

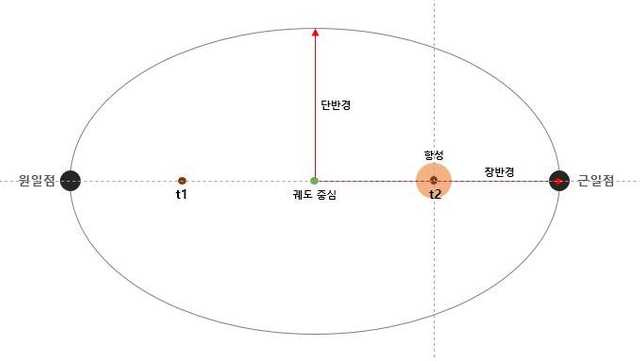

Since planetary orbits are elliptical, they have two foci. Typically the star occupies one of these foci. The aphelion is the point farthest from the star, and the perihelion is the closest. Parabolic orbits have an aphelion at infinity, so they only have a perihelion.

Keplerian Elements

Now that we’ve covered the basic terms, let’s look at the Keplerian elements that define the shape, size, and orientation of an orbit.

The Keplerian elements consist of: the semi-major axis and eccentricity (which define the orbit’s shape and size), the inclination and longitude of the ascending node (which define the orbital plane), and finally the argument of periapsis (which defines the orbit’s orientation) along with the time of periapsis passage (which pins down the body’s position at a specific time).

Semi-major Axis

Since planetary orbits are elliptical, they’re defined not by a radius but by a semi-major axis and semi-minor axis. The semi-major axis is the point on the orbit farthest from the orbital center, while the semi-minor axis is the closest point.

The difference from aphelion/perihelion is that the reference point is the center of the orbit, not the star. Parabolic and hyperbolic orbits have an infinite semi-major axis, so they only have a semi-minor axis.

The Keplerian elements only deal with the semi-major axis (not the semi-minor axis) because what matters for orbital energy calculations is the average distance of the orbiting body, not the orbit’s shape. The semi-major axis represents the overall size of the orbit, while the semi-minor axis merely indicates how squashed it is — not a suitable metric for energy calculations.

For this reason, celestial mechanics generally uses the semi-major axis, and Kepler’s equation does the same.

Eccentricity

Eccentricity is simply a measure of how squashed an ellipse is. In the geometric definition, the eccentricity of an ellipse is:

Here is the semi-major axis and is the semi-minor axis. However, the eccentricity used in Keplerian orbits has a slightly different formula.

The standard formula for an ellipse’s eccentricity only describes the geometric squashing without considering factors like gravity or energy, so it’s not suitable for Keplerian orbits, which are based on the interaction between a body’s kinetic energy and gravitational forces.

To calculate the eccentricity of a Keplerian orbit, you need to account for physical dynamics like kinetic energy and angular momentum:

The solution of this equation is called the orbital eccentricity.

Here, is the total energy of the body in orbit, is the angular momentum, is the reduced mass, and is the coefficient for the inverse-square law central force. The inverse-square law means a force’s magnitude is inversely proportional to the square of the distance — in this case, that force is gravity.

Since I’ll be using data where the eccentricity is already provided, I don’t actually need to calculate all this. Just knowing that it differs from the standard eccentricity formula is enough.

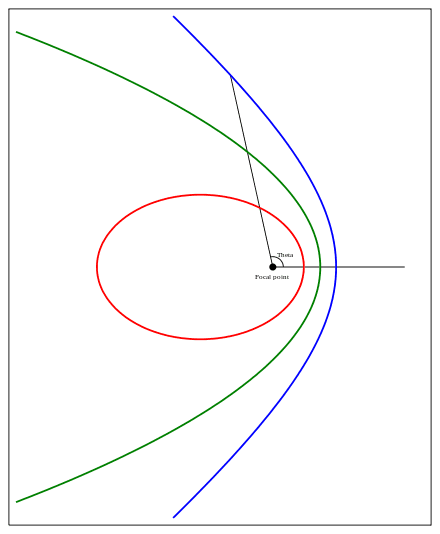

Keplerian orbital eccentricity takes four forms:

- Circular orbit:

- Elliptical orbit:

- Parabolic orbit:

- Hyperbolic orbit:

Earth’s orbital eccentricity is currently about 0.0167, making it nearly circular. Mercury, the planet with the highest eccentricity in the solar system at 0.2056, receives roughly twice as much solar radiation at perihelion compared to aphelion.

Pluto used to be the champion in this category with 0.248, but as we all know, it’s been demoted… (Adiós…)

Comets have quite varied eccentricities. Periodic comets typically range from 0.2 to 0.7, while some with extremely elongated orbits approach nearly 1.

For example, the well-known Halley’s Comet has an eccentricity of 0.967 and takes 76 years to complete one orbit due to its extremely elongated path. Its next approach is in 2061, by the way.

Inclination

This is the angle between the star’s ecliptic plane and the orbit. If the inclination exceeds 90°, the body is orbiting in the opposite direction compared to bodies with inclinations between 0° and 90°.

Longitude of the Ascending Node

As mentioned, the ascending node is the point where a body crosses the reference plane from south to north while following its orbit. The ascending node is expressed as a longitude — the angle measured counterclockwise from the vernal equinox along the ecliptic to the ascending node.

This allows us to define the position of the ascending node in a 3D coordinate system.

Argument of Periapsis

The argument of periapsis is the angle from the ascending node to the periapsis, measured within the orbital plane. As the term “periapsis” suggests, this angle is measured from the gravitational focus of the orbit, not the center of the ellipse.

This value indicates how much the orbital ellipse is rotated relative to the reference plane (like the ecliptic). If the argument of periapsis is 0°, the ascending node and periapsis coincide, meaning the body is closest to its star at the moment it crosses the ascending node. If it’s 90°, the body is at its closest approach when it’s at the point farthest north of the reference plane.

Time of Periapsis Passage

This marks the time when the body passes through periapsis.

Closing Thoughts

In the next post, we’ll implement orbital calculations in code. That wraps up this glossary of astronomical terms and introduction to the Keplerian elements.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Implementing Planetary Motion

Programming/Graphics[Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 2. Coding

Programming/Graphics[Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 1. What is Gravity?

Programming/GraphicsUsing PayPal's Express Checkout RESTful API

Programming/Tutorial[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes

Programming/JavaScript