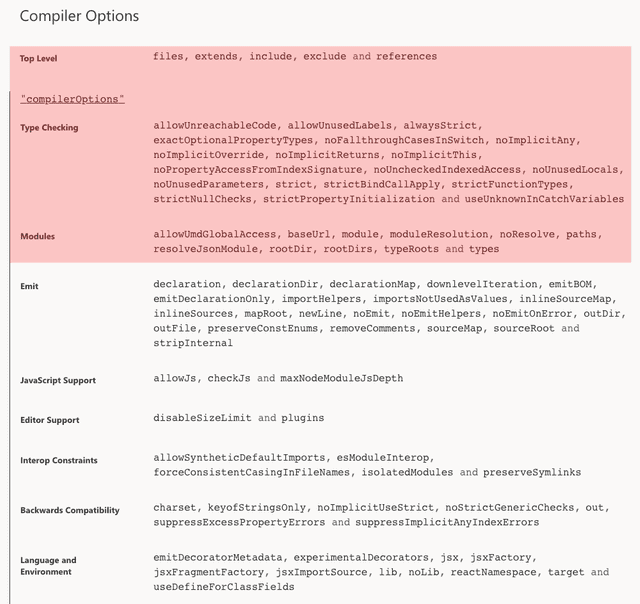

[Everything About tsconfig] Compiler Options / Modules

![[Everything About tsconfig] Compiler Options / Modules [Everything About tsconfig] Compiler Options / Modules](/static/bd1dff385c51f51e8cdfb5ce1bf76e9e/01fb2/thumbnail.png)

Following up on my previous post [Everything About tsconfig] Compiler options / Type Checking, this post covers the module-related options in tsconfig’s compiler settings.

These options control which module system TypeScript should follow when compiling modules, which paths to include in compilation, what module format the compiled JavaScript should use, and so on. They come up more often when building TypeScript libraries than when building typical applications.

allowUmdGlobalAccess

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

true |

Allows access to UMD modules |

false (default) |

Disallows access to UMD modules |

The allowUmdGlobalAccess option controls whether TypeScript modules can access UMD (Universal Module Definition) modules that expose themselves as properties on the global object.

When this option is disabled, you cannot access global variables like jQuery’s $ directly; you must import the module using an import statement.

Libraries built using the UMD pattern typically have type declarations that look like this:

export const doThing1: () => number;

export const version: string;

export interface AnInterface {

foo: string;

}

export as namespace myLibrary;When a type file exports a namespace this way, TypeScript assumes the module is implicitly assigned to a global variable named myLibrary. That’s why including this type declaration in your source lets you access the module’s contents through the myLibrary namespace.

If allowUmdGlobalAccess is disabled, you’ll encounter this error:

const b = myLibrary.doThing1();

// 'myLibrary' refers to a UMD global, but the current file is a module. Consider adding an import instead.ts(2686)

export {}Enabling allowUmdGlobalAccess allows access to UMD modules exported as namespaces. However, explicitly importing modules with the import keyword is safer than relying on modules implicitly declared in the global scope. Unless you have no choice, it’s better to keep this option enabled.

baseUrl

The baseUrl option specifies the base directory for resolving relative module paths.

myProject

├── index.ts

├── utils

│ └── foo.ts

└── tsconfig.jsonFor instance, in the structure above, to import the foo.ts module from index.ts using a relative path, you’d write ./utils/foo — where ./ marks the current location as the starting point.

But if you think about it, even when using relative paths, the base location itself doesn’t change that often.

myProject

├── index.ts

├── utils

│ └── foo.ts

├── remotes

│ └── bar.ts

└── tsconfig.jsonIf a module in remotes/bar wants to access the utils/foo module in this structure, it would use ../utils/foo — climbing up to the project root and then descending again.

The baseUrl option eliminates this repetitive “journey to root” whenever you use relative paths.

{

"include": ["src/*"],

"compilerOptions": {

"baseUrl": "./"

}

}The relative path in baseUrl is relative to where tsconfig is located — typically the project root. With this configuration, when you use relative paths to access modules, TypeScript searches starting from the root specified in baseUrl.

import { foo } from 'utils/foo'; // Actually .(root)/utils/foo

import { bar } from 'remotes/bar'; // Actually .(root)/remotes/barUsing baseUrl this way lets you write relative paths as if they were absolute, without repeatedly navigating to the root with ./ or ../.

paths

The paths option provides a mapping that tells the compiler where to search when you specify certain module names.

{

"compilerOptions": {

"baseUrl": "./src",

"paths": {

"app/*": ["app/*"],

"config/*": ["app/_config/*"],

"environment/*": ["environments/*"],

"shared/*": ["app/_shared/*"],

"helpers/*": ["helpers/*"],

"tests/*": ["tests/*"]

}

}

}Paths in the mapping are calculated relative to baseUrl, so you must set baseUrl to use the paths option. In the example above, app/* means ./src/app/*, and when you import with import foo from 'app/math', TypeScript automatically searches the corresponding path ./src/app/math and loads the module.

If TypeScript can’t find the module after searching all locations in paths, it performs additional searching according to the strategy set in moduleResolution.

Path mapping itself is quite simple, but people often forget that path mapping always starts relative to baseUrl, leading to mistakes.

myProject

├── src

│ └── index.ts

├── node_modules

│ └── foo

└── tsconfig.jsonConsider a project with this structure where baseUrl is set to ./src. How would you map the foo path to node_modules/foo?

A common mistake is setting "foo": "./node_modules/foo" based on the location of tsconfig.json. Since you’re working in tsconfig.json, it’s natural to specify paths relative to that file without thinking.

But path mapping is relative to baseUrl, so in this case src is the reference point. You’d need to write "foo": "../node_modules/foo".

It’s easy to forget this and map paths relative to tsconfig.json’s location, then fail to resolve modules. Keep this in mind.

module

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

CommonJS (default) |

Compiles modules to CommonJS format. |

AMD |

Compiles modules to Asynchronous Module Definition format. |

UMD |

Compiles modules using the Universal Module Definition design pattern. |

System |

Compiles modules to System.js format. |

ES6, ES2015, ES2020, ESNext |

Compiles modules to ESM (ES Module) format. |

The module option sets which module system the compiled JavaScript modules will use.

Of course, the official module system specified by ECMAScript is ESM using import and export keywords, but realistically, not many browsers support this system yet. And while Node.js added support for ESM without the --experimental-modules flag in version 12.0.0, the ESM system isn’t widespread across the entire ecosystem. (Node.js still heavily uses CommonJS)

For these reasons, it’s not practically feasible to compile all our modules to ESM. We need to be able to choose an appropriate module system for the situation.

This post won’t cover everything about JavaScript module systems, but let’s briefly look at the characteristics of each. Imagine a simple application with two modules:

// utils/math.ts

export const add = (x: number) => (y: number) => x + y;// index.ts

import { add } from './utils/math';

export const add2 = add(2);The index.ts module imports the add function from utils/math.ts, uses currying to create add2, and exports it. Let’s see how index.ts changes when compiled with each module system and what each system’s characteristics are.

CommonJS

"use strict";

exports.__esModule = true;

exports.add2 = void 0;

var math_1 = require("./utils/math");

exports.add2 = (0, math_1.add)(2);CommonJS, true to its “Common” name, represents a module system designed for using JavaScript modules freely not just in browsers but also in server environments and desktop applications.

For this reason, server-side runtimes like Node.js still commonly use the CommonJS system, so if you’re building a library for server-side use, you should consider using CommonJS.

CommonJS assigns modules to properties of the exports or module.exports object and synchronously loads modules directly using the global require function. In the example above, you can see the module being assigned to the math_1 variable through the require function, and the add2 function being assigned to the exports.add2 property.

Because the require function loads modules synchronously when executed, CommonJS even allows tricks like “if this, load module A; if that, load module B” using if statements.

AMD

define(["require", "exports", "./utils/math"], function (require, exports, math_1) {

"use strict";

exports.__esModule = true;

exports.add2 = void 0;

exports.add2 = (0, math_1.add)(2);

});AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition), as its name suggests, is a module system that loads modules asynchronously.

The original CommonJS was designed assuming synchronous module loading, which sparked active discussions about implementing asynchronous module loading. During these discussions, some people who didn’t agree with CommonJS’s core principle of “JavaScript modules that work in every environment” emerged, and they split off to form the AMD group.

Browser environments are inherently different from servers: modules need to be fetched from a server to be used. So it’s more efficient to asynchronously fetch only the needed parts of modules from the server rather than loading all necessary modules at once and executing them. But for the CommonJS group aiming for “JavaScript modules that work in every environment,” unifying these environmental differences was challenging.

This led people with the mindset “let’s at least get browsers right” to split off and create AMD, which is why AMD focuses specifically on asynchronous module calls in browsers. (CommonJS did later add asynchronous module loading separately)

Since AMD ultimately split from CommonJS, the two systems provide many compatible features, allowing techniques like wrapping existing CommonJS modules in AMD format.

In the example above, you can see AMD’s define function pulling in CommonJS’s require and export functions. The internal structure is basically similar to CommonJS, but the key difference is that instead of loading modules via require, modules are injected through the third argument math_1 of the define function.

UMD

(function (factory) {

if (typeof module === "object" && typeof module.exports === "object") {

var v = factory(require, exports);

if (v !== undefined) module.exports = v;

}

else if (typeof define === "function" && define.amd) {

define(["require", "exports", "./utils/math"], factory);

}

})(function (require, exports) {

"use strict";

exports.__esModule = true;

exports.add2 = void 0;

var math_1 = require("./utils/math");

exports.add2 = (0, math_1.add)(2);

});UMD (Universal Module Definition) is less a module system and more a design pattern for creating something that can be used universally across various environments.

Because UMD is a pattern, unlike AMD or CommonJS which typically use libraries like RequireJS, developers must write code using the UMD pattern themselves. Simply put, as shown in the example, using an IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression) to branch directly in your source code is the UMD pattern.

The example shows that if module and module.exports exist, it uses the CommonJS system; if the define function exists, it uses AMD. This way, the UMD pattern can provide a consistent experience regardless of which module system the environment uses.

UMD === I didn't know what you'd like, so I prepared every module system

UMD === I didn't know what you'd like, so I prepared every module system

Additionally, if an environment supports neither CommonJS nor AMD, there’s a last-resort UMD pattern approach: inserting the module as a property of global objects like globalThis, window, or global.

However, this pollutes the global scope and should be avoided when possible. And since it’s rare for modern JavaScript runtime environments to be forced into situations where no module system is supported, TypeScript doesn’t appear to use this approach.

System

System.register(["./utils/math"], function (exports_1, context_1) {

"use strict";

var math_1, add2;

var __moduleName = context_1 && context_1.id;

return {

setters: [

function (math_1_1) {

math_1 = math_1_1;

}

],

execute: function () {

exports_1("add2", add2 = math_1.add(2));

}

};

});If the UMD pattern is “I didn’t know what you’d like, so I prepared everything” in design pattern form, SystemJS is that concept implemented as a library. (Even more ambitious)

SystemJS is a module loader, so it doesn’t concern itself with how modules are defined — it just loads modules already defined in CommonJS, AMD, or ESM formats.

SystemJS was quite popular around 2016 when the ECMA Foundation announced ESM using import and export keywords as the official ES6 module spec, because browsers at the time didn’t support this spec.

The official spec for modules had been decided, but browser vendors were slow to implement it. You couldn’t use ESM even if you wanted to. SystemJS bridged this gap. It was implemented using the es-module-loader polyfill to load ESM-format modules.

This raises a question: “Even if you load modules that browsers don’t support, you can’t execute them without transpilation. How does SystemJS solve this?” The answer was surprisingly close at hand.

I don't really get complex stuff — just import babel and run transpilation at runtime

I don't really get complex stuff — just import babel and run transpilation at runtime

Exactly. Using this method, it doesn’t matter if the target module uses ES2020 or TypeScript, or if its module system is CommonJS or AMD. Of course, this isn’t a built-in SystemJS feature — you need the systemjs-babel extension — but the solution approach itself is impressively bold.

However, transpiling modules at runtime isn’t just about transpilation: you also need to determine module dependencies, and if you’re using TypeScript, you need to compile after static type checking. Naturally, performing these heavy operations at runtime instead of build time hurts performance.

In 2021, as everyone knows, these heavy operations can be done entirely at build time with no issues, so SystemJS is rarely used unless there’s a special situation.

ES Module

import { add } from './utils/math';

export var add2 = add(2);ESM (ES Module) is the module system officially defined by the ECMA Foundation for the JavaScript ecosystem.

That’s why, unlike CommonJS or AMD which rely on separate functions like require or define to load modules, ESM uses the import and export keywords to load modules.

ESM, which appeared in 2015, was a latecomer compared to CommonJS and AMD which had been in use since 2009. It also introduced many changes like mandatory inclusion of the use strict directive in modules and this not pointing to the global window object.

These constraints meant applications using CommonJS or AMD couldn’t easily migrate, and that situation continues today.

That’s why even now, to use ESM in native JavaScript environments, you need to add the type="module" attribute to script tags or add a "type": "module" field to package.json.

Of course, many vendors now support ESM compared to before, but to safely use ESM, you still need to combine bundlers like Webpack and transpilers like Babel to determine module dependencies at build time and convert them to a form the runtime can understand. Depending on the runtime environment, this can make ESM a cumbersome format to use — something to keep in mind.

However, ESM has one advantage that overshadows all these drawbacks: tree-shaking is much easier when bundling modules with Webpack.

Webpack’s ModuleConcatenationPlugin merges modules into a single closure to achieve better performance in browser environments. The choice between CommonJS and ESM significantly affects the output.

// CommonJS

(() => {

"use strict";

/* harmony import */ var _utils__WEBPACK_IMPORTED_MODULE_0__ = __webpack_require__(12);

var add2 = (0,_utils__WEBPACK_IMPORTED_MODULE_0__/* .add */ .DG)(2);

})();When bundled with Webpack, CommonJS modules are loaded through a __webpack_require__ function. The problem is this doesn’t just load the add function inside the module — it loads the entire module.

The next line (0,_utils__WEBPACK_IMPORTED_MODULE_0__/* .add */ .DG) shows access to the DG property of the loaded module, which is the obfuscated name of the add function.

Since CommonJS assigns values to properties of the global exports object, it’s hard to determine “this module only uses function A.”

But ESM modules can export each desired value separately using the export keyword, making it much easier to determine detailed dependencies.

// ESM

/******/ (() => { // webpackBootstrap

/******/ "use strict";

// CONCATENATED MODULE: ./utils/math.js**

var add = (a) => (b) => a + b;

// CONCATENATED MODULE: ./index.js**

var add2 = add(2);

/******/ })();Looking at an ESM module bundled with Webpack, there’s no module-loading code at all — the function from inside the module was even inlined.

Of course, the add function I imported is very small, which allows this representation. But the key point is that only that “specific function” from inside the module was imported.

As mentioned, ESM makes detailed dependency tracking easy through import and export keywords, enabling efficient separation of used and unused code at build time.

Because of this powerful tree-shaking advantage, most popular libraries except Lodash officially support ESM.

moduleResolution

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

Node |

Uses Node strategy to resolve modules. Default when module option is CommonJS. |

Classic |

Uses Classic strategy to resolve modules. Default when module option is not CommonJS. |

The moduleResolution option handles the process TypeScript uses to determine exactly what a module import refers to. This is too difficult to explain in words, so let’s look at code.

First, TypeScript uses two main methods for defining module paths: relative and absolute.

import { add } from './utils/math'; // Relative path

import { debounce } from 'lodash'; // Absolute pathRelative paths use identifiers like . (current location) or .. (parent directory) to specify a starting point, allowing precise indication of module location. Absolute paths, on the other hand, just specify the module name, so TypeScript needs to embark on a journey to find the exact module location based on specific rules.

Also, since neither relative nor absolute paths specify file extensions, TypeScript needs to figure out which extension the file has — math.ts, math.d.ts, etc.

That’s why TypeScript needs a strategy for finding exact module locations. The moduleResolution option lets you choose between Classic and Node strategies.

Both strategies follow basically similar methods for finding module locations.

When finding modules using relative paths like import { add } from './math', the directory to search is clear, so it only searches within that directory. When finding modules using absolute paths like import { add } from 'math', the directory isn’t clear, so it starts searching in the directory containing the file that imported the module, then moves up one level to the parent directory, then another level up, and so on.

The difference between Classic and Node strategies lies in which file extensions to look for and where to search first.

Classic

The Classic strategy is essentially TypeScript’s default module resolution strategy, also used for compatibility with older TypeScript versions.

The Classic strategy searches for modules imported with relative paths starting from the importing module’s location, in the order *.ts, *.d.ts.

// /root/src/index.ts

import { add } from './math';

/root/src/math.ts

/root/src/math.d.ts

As mentioned, when using relative paths, the directory location to search is clear, so TypeScript only searches candidate extensions and terminates if the module isn’t found.

For modules using absolute paths like import { add } from 'math', TypeScript starts from the current importing path and climbs up the parent directories one level at a time.

// /root/src/index.ts

import { add } from 'math';

/root/src/math.ts

/root/src/math.d.ts

/root/math.ts

/root/math.d.ts

/math.ts

For absolute paths, TypeScript starts searching from /root/src where the importing file is located. If it doesn’t find the module in this directory, it climbs up one level and searches again. If it reaches the root and still can’t find the module, it terminates.

Node

The Node strategy mimics how Node.js finds modules. Unlike the Classic strategy, Node doesn’t just search for *.ts or *.d.ts extensions — it searches a wider variety of module formats.

For relative paths, similar to Classic, TypeScript searches within the specified directory in this order:

// /root/src/index.ts

import { add } from './math';

/root/src/math.ts

/root/src/math.tsx

/root/src/math.d.ts

/root/src/math/package.json(only if usingtypesfield)

root/src/math/index.ts

root/src/math/index.tsx

root/src/math/index.d.ts

It looks like a lot was added, but basically it’s the same as Classic — searching files in the specified directory — except it additionally searches for *.tsx extensions, the types property in package.json, and index.* files in directories with the same name as the module.

When searching for relatively-pathed modules, both Node and Classic strategies use similar directory tree traversal orders. But the difference becomes larger when finding absolutely-pathed modules.

That’s because the Node strategy, unlike Classic, searches node_modules directories when finding absolutely-pathed modules.

// /root/src/index.ts

import { add } from 'math';

/root/src/node_modules/math.ts

/root/src/node_modules/math.tsx

/root/src/node_modules/math.d.ts

/root/src/node_modules/math/package.json(only if usingtypesfield)

/root/src/node_modules/@types/math.d.ts

/root/src/node_modules/math/index.ts

/root/src/node_modules/math/index.tsx

/root/src/node_modules/math/index.d.ts

/root/node_modules/math.ts(moves to parent directory and repeats)…

Using the Node strategy, TypeScript first searches the node_modules directory in /root/src where the file calling the math module is located.

It searches for *.ts, *.tsx, *.d.ts files and the types field in package.json just like with relative paths, then searches the @types directory and index files in directories with the same name as the module.

If it doesn’t find the desired module after one search pass, it moves to the parent directory and repeats. If it reaches the root, searches globally-installed modules on the local machine, and still can’t find the module, it terminates.

This search process isn’t identical to how Node.js finds modules, but it’s very similar. Node.js first looks for files with the same name as the module, then looks for the file at the path in package.json’s main field, and finally searches for index files in directories with the same name. TypeScript’s Node strategy mimics this search process.

The TypeScript docs say it’s not particularly complex compared to Node.js’s method, so don’t worry. But honestly, Node.js’s package search method itself is inefficient. That’s why starting from TypeScript 4.0, modules that aren’t imported no longer have their type information searched through this process.

noResolve

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

false (default) |

Resolves all modules included in the application. |

true |

Only resolves modules explicitly included in the application. |

By default, the TypeScript compiler tries to compile all modules included in the application. Even if a file isn’t included in the tsconfig root’s include or files fields, if it’s imported somewhere in the application using an import statement or /// <reference path="..." /> directive, that module is also a compilation target.

In a sense, this implicitly includes modules in the compilation targets. Setting noResolve to true prevents this implicit module compilation.

// tsconfig.json

{

"include": ["src/index.ts"],

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dist",

"noResolve": true

}

}// src/index.ts

import { add } from './utils/math';

export const add2 = add(2);In this example, the include field only contains src/index.ts, not the utils/math module.

When noResolve is false, the utils/math module used in index.ts compiles without issues. But when it’s true, you get an error saying the module can’t be found.

src/index.ts:1:21 - error TS2307: Cannot find module './utils/math' or its corresponding type declarations.

1 import { add } from './utils/math';Only modules explicitly declared in the include or files fields are compiled. For the same reason, modules imported using directives like /// <reference path="..." /> are also excluded from compilation if they’re not in those fields.

The noResolve option helps with easier module management by forcing developers to explicitly declare TypeScript’s compilation targets. However, because it excludes even directive-imported modules from compilation, when using libraries like Next.js that import type definition files via directives, it’s better for your mental health to just use the default false.

resolveJsonModule

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

false (default) |

Disallows importing modules with *.json extensions. |

true |

Allows importing modules with *.json extensions. |

The resolveJsonModule option determines whether to allow importing modules implemented as JSON files.

If this option is false, TypeScript throws an error saying it can’t find the module when you import a JSON module.

// me.json

{

"name": "evan-moon",

"age": 12,

"role": "Frontend Engineer"

}import me from './me.json';

// Cannot find module './settings.json'. Consider using '--resolveJsonModule' to import module with '.json' extension.Enabling resolveJsonModule lets you import and use JSON modules just like regular TypeScript modules, and it even analyzes the file to automatically infer types.

However, since inference using Enum or Union Types is impossible, all values are inferred as primitive types like string or number. If you need to enforce strong type declarations, it’s better to declare your model using TypeScript modules instead of JSON modules.

rootDir

The rootDir option determines which directory to treat as the root when maintaining the current structure after compiling modules.

By default, TypeScript maintains the input directory structure when compiling and outputting files. The rootDir option lets you set which directory to treat as the root.

If you don’t set this option, TypeScript automatically finds the file that serves as the application’s entry point and sets the directory containing that file as the root for the output directory structure.

myProject

├── src

│ ├── index.ts

│ └── utils

│ └── math.ts

└── tsconfig.json// tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dist"

}

}Consider a project with this structure. When rootDir isn’t specified, TypeScript finds the application’s entry point src/index.ts and recognizes src as the root.

The output directory will have this structure with src as the root:

dist

├── index.ts

└── utils

└── math.tsHowever, if you set rootDir to . (current path), the output directory structure changes.

// tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dist",

"rootDir": "."

}

}dist

└── src

├── index.ts

└── utils

└── math.tsSince I changed the root directory to the current myProject directory where tsconfig.json is located, the output directory dist has exactly the same structure as the original project directory, including the src directory.

While it’s a fairly simple operation, there’s one caveat when using this option: rootDir doesn’t affect compilation targets at all.

This means if you use rootDir, all compilation target files must be located under that directory.

myProject

├── src

│ ├── index.ts

│ └── utils

│ └── math.ts

├── foo.ts

└── tsconfig.json{

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dist",

"rootDir": "./src",

"include": "*"

}

}Looking at this configuration, the root directory is set to src, and the include option says to compile all files.

The problem is that one of these “all files,” foo.ts, isn’t inside the src directory. The settings contradict each other.

Even though rootDir sets the root directory, TypeScript won’t automatically exclude foo.ts from compilation — instead, it throws this error:

File ‘/Users/john/myProject/foo.ts’ is not under ‘rootDir’ ‘/Users/john/myProejct/src’. ‘rootDir’ is expected to contain all source files.

As this error shows, if you set a root directory with rootDir, all source files must be inside that root directory. Even if you use include to designate files outside the root directory as compilation targets, TypeScript won’t automatically compile them.

rootDirs

The rootDirs option creates a kind of virtual root. This is much easier to understand with code than words, so let’s look at an example right away.

myProject

├── core

│ └── index.ts

├── utils

│ └── math.ts

└── tsconfig.jsonImagine an application with this structure. How would you import the utils/math.ts module in core/index.ts?

Without using the paths option, you’d use a relative path to climb up one level to the parent directory and access the module.

// core/index.ts

import math from '../utils/math';The rootDirs option creates a virtual root so that modules in the core and utils directories can be used as if they were in “a single directory.”

{

"compilerOptions": {

"outDir": "./dist",

"rootDirs": ["core", "utils"]

}

}// core/index.ts

import math from './utils/math'; // Use as if in the same directoryEven if the directory depth is deep like core/components/Foo/index.tsx, registering the directory in rootDirs lets directories registered in rootDirs import modules as if they’re always in the same directory.

And because rootDirs implements this by creating a kind of “virtual directory,” it has no effect whatsoever on the output directory structure after compilation. It’s literally virtual.

The rootDirs option is convenient in that it lets you use simple relative paths even with deep directory structures.

However, using this configuration creates a disconnect between the actual directory structure and the paths used in code to access modules, making the code harder to understand intuitively. And to understand the cause of this disconnect, you need to look at tsconfig.json — a potentially sad situation. Keep this in mind.

typeRoots

By default, TypeScript automatically includes files under @types package directories in compilation targets. Following the resolve strategy described earlier, it searches @types directories inside node_modules while climbing up directories: ./node_modules/@types, ../node_modules/@types, etc.

But using the typeRoots option, you can specify where TypeScript should find type files instead of searching everywhere.

{

"compilerOptions": {

"typeRoots": ["./typings", "./node_modules/@types"]

}

}Paths in typeRoots are relative to tsconfig.json. Also, while this example includes the ./node_modules/@types directory in the option, it’s actually unnecessary.

When typeRoots is specified, TypeScript abandons its existing module search strategy and only looks for type declaration modules in the paths in the array. This is more efficient than the existing module search strategy of continuously climbing up parent directories searching for type declaration modules.

types

As explained, TypeScript automatically includes all files under @types package directories in compilation targets, which spreads type declarations into the global scope.

Because these type declarations exist in the global scope, we can use things like the process object from @types/node without separate type declarations.

But using the types option, you can include only specific packages’ types in the global scope.

{

"compilerOptions": {

// Only import @types/node, @types/jest, @types/express

"types": ["node", "jest", "express"]

}

}With this configuration, types for node, jest, and express packages are included in the global scope, automatically type-checking statements like import express from 'express';. But other libraries not included here require you to import their type declaration modules directly.

The key thing to note is that the types option targets type declaration modules that exist inside @types package directories.

For example, the date library moment doesn’t require installing a separate type package like @types/moment — it has built-in type declaration modules.

{

"name": "moment",

// ...

"main": "./moment.js",

"jsnext:main": "./dist/moment.js",

"typings": "./moment.d.ts",

// Includes type declaration file internally

}In this case, the statement import moment from 'moment' imports the library and automatically includes moment.d.ts as a compilation target, so you can naturally use the types.

The types option only targets type declaration modules inside @types/* packages and only applies when TypeScript spreads those type declarations into the global space. Don’t get confused.

Closing Thoughts

That wraps up the third installment in the tsconfig series: the Modules edition. While there aren’t that many module-related options, since they deal with which module system to use during compilation and which module resolution strategy to use, the explanations got lengthy.

And now that I’ve written this far, a realization hits me…

Wait... I've only written this much...?

Wait... I've only written this much...?

I knew tsconfig had many options, but I never imagined it would be this challenging. (First time my wrist hurt from writing…)

Of course, if I just translated the official docs line by line, I’d finish quickly. But the whole point of starting this post series wasn’t just to provide that level of information — it was to do a complete analysis of tsconfig, so I’ll keep pushing forward.

In the next post, I’ll discuss options that control TypeScript’s behavior when generating output files.

That concludes this post: [Everything About tsconfig] Compiler options / Modules.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

[All About tsconfig] Compiler options / Emit

Programming/Tutorial/JavaScript[Everything About tsconfig] Compiler Options / Type Checking

Programming/Tutorial/JavaScript[Everything About tsconfig] Root Fields

Programming/Tutorial/JavaScriptBeyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingWhy Do Type Systems Behave Like Proofs?

Programming