How Do You Actually Use Regex?

A journey of finding order in irregular data

In my previous post, Finding Patterns in Irregularity: A Guide to Regular Expressions, I covered the basics of how regex works.

But no matter how well you understand the fundamentals, the moment you actually need to use regex in a real situation, your mind tends to go blank.

So in this post, I’d like to walk through several real-world scenarios I’ve encountered at work, with examples and explanations of how I used regex to solve them.

Regex sees the most action in three situations: “validating user input,” “extracting desired information,” and “reformatting strings.” Let’s define problems in each category and solve them with regex.

Validating User Input

The most common place you’ll encounter regex in practice is when validating user input.

You learn this naturally as you build products, but users absolutely will not use your product the way you designed it. Blindly trusting user-submitted data and shipping it straight to the server is a fairly dangerous thing to do.

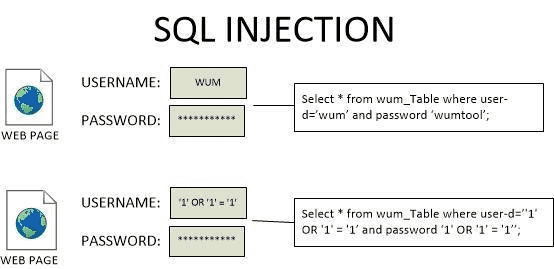

You told them to enter an email address, but they entered a phone number. In the worst case, someone with malicious intent might inject a script or query and send it to the server.

Modern backend frameworks and ORMs handle injection attacks automatically,

Modern backend frameworks and ORMs handle injection attacks automatically,but raw queries are still used for performance reasons — never let your guard down

That’s why client-side developers write validation logic to verify that user input is correct, and regex is incredibly useful in this process.

Validating Email Addresses

Email is one of the most common data formats you’ll receive from users. And since email addresses have clearly defined fields and limited rules, validating whether a given string is a proper email address isn’t terribly difficult.

The specifics may vary slightly between MBPs (Mailbox Providers), but according to RFC 2822 § Addr-spec specification, which defines the internet message protocol, an email address can be described as a string with the following pattern:

An email address consists of a local part,

@, and a domain.The local part may contain letters, digits, and special characters such as

!#$%&'*+-/=?^_{|}~. The.character is also allowed, but the local part must not start or end with..The domain consists of a host and domain identifier connected by

.(e.g., google.com).The local part and domain are connected by

@.

Since email addresses follow a well-defined pattern, we can validate them through simple pattern matching with regex.

The Local Part

The local part of an email can contain letters and digits, so we can use \w — the word group that matches both letters and digits — to handle this easily. It also allows special characters like !#$%&'*+-/=?^_{|}~, so a custom group like [\w!#$%&'*+-/=?^_{|}~] covers all valid characters for the local part.

This pattern must appear at least once. If it appears zero times, the local part is empty, which isn’t a valid email address. So we append the + quantifier at the end, meaning “one or more occurrences.”

^[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+This is the basic pattern for an email local part. But RFC 2822 has one more finicky rule: ”. is allowed, but the local part must not start or end with ..”

Checking that a string doesn’t start or end with . is straightforward using the ^ and $ anchors, but handling . appearing in the middle requires a bit more thought.

The simplest way to express “a character that may or may not appear in the middle” is actually quite intuitive:

.always appears in the middle of the local part. In other words,.must always be followed by the[\w!#$%&'*+-/=?^_{|}~]pattern.

To put it more precisely: the pattern .something may or may not appear within the local part, but if it does appear, there must always be other characters after the ..

Expressed as regex on its own:

(?:\.[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+)*Let’s start with the (?: and ) wrapping. This is the same grouping mechanism as the capturing feature I explained in the previous post.

Capturing groups actually serve double duty — they capture and they group multiple expressions. When you add ?: at the beginning of a group (), you’re saying “I want the grouping but not the capturing.” That’s why it’s called a “Non-Capturing Group.”

Inside the group, \. means the literal . character. Without the escape, the regex engine would interpret . as the character class meaning “any character,” so we escape it to match the literal dot.

After that comes the same [\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+ pattern we used before — meaning at least one character from this set must follow the ..

Finally, since this entire pattern may or may not appear, we append the * quantifier (zero or more) after the closing ).

Combining this with the earlier [\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+ pattern gives us a complete regex for valid email local parts:

const regex = /^[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+(?:\.[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+)*$/g;// Letters + digits

regex.test('bboydart91'); // true

// Dot in the middle

regex.test('bboydart91.test'); // true

// Starts or ends with dot

regex.test('.bboydart91'); // false

regex.test('bboydart91.'); // falseThe Domain

Now that we’ve defined a regex pattern for valid email local parts, all that’s left is defining one for valid domains.

According to RFC 2822, the domain is “a host and domain identifier connected by .” — so the matching conditions aren’t particularly demanding.

But look closely: the spec says the host and domain identifier are connected by ., but it doesn’t say . appears only once. So we need to handle cases like google.com as well as google.co.kr where . appears multiple times.

These ambiguous patterns are easily handled with the Non-Capturing Group we just used:

const regex = /^(?:\w+\.)+\w+$/g;(?:\w+\.)+ expresses that a word group followed by . (like google.) must appear at least once, and the trailing \w+ requires that another word group must follow the final ..

// Both host and domain identifier present

regex.test('google.com'); // true

regex.test('google.co.kr'); //true

// Missing domain identifier

regex.test('google.'); // false

regex.test('google'); // false

// Missing host

regex.test('.com'); // false

regex.test('.co.kr'); // falseCombining the Local Part and Domain Patterns

Now that we have regex patterns for both valid local parts and domains, we just need to join them with @ to satisfy the final condition: “the local part and domain are connected by @.”

// Local part pattern: ^[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+(?:\.[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+)*

// Domain pattern: (?:\w+\.)+\w+$

const regex = /^[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+(?:\.[\w!#$%&'*+/=?^_{|}~-]+)*@(?:\w+\.)+\w+$/g;regex.test('bboydart91@gmail.com'); // true

regex.test('bboydart.evan@gmail.com'); // true

regex.test('bboydart@naver.co.kr'); // true

regex.test('.bboydart91@gmail.com'); // false

regex.test('bboydart91@gmail'); // false

regex.test('bboydart91.@gmail.com'); // falsePhone Numbers

Phone numbers are another piece of data you frequently receive from users. I touched on this in the previous post, Finding Patterns in Irregularity, but I’ll revisit it here for readers who may have missed that one.

Phone number formats vary by country, but the core idea is universal: digits grouped in a predictable structure separated by delimiters. Let’s use US phone numbers as an example. A standard US phone number has a 3-digit area code, a 3-digit exchange code, and a 4-digit subscriber number:

'212-555-1234'

'(212) 555-1234'

'2125551234'Since phone numbers are just digits repeating in fixed-length groups, the regex to match them is straightforward:

const regex = /^\d{3}-?\d{3}-?\d{4}$/g;regex.test('2125551234'); // true

regex.test('212-555-1234'); // true

regex.test('3015551234'); // true

regex.test('301-555-1234'); // trueThe digit counts in each field are clearly defined, so simple quantifiers do the job. The hyphens between fields may or may not be present, so we use the ? quantifier (zero or one) to handle them.

The regex itself is straightforward, but there’s a subtle mistake developers sometimes make in practice:

// Pattern that only matches numbers starting with a specific area code

/212-\d{3}-\d{4}/;This pattern only captures phone numbers with the 212 area code. If your validation is too narrow, you’ll reject perfectly valid phone numbers from other regions.

The 1996 "Gulliver Phone" — a nostalgic relic from the early mobile era

The 1996 "Gulliver Phone" — a nostalgic relic from the early mobile era

The takeaway: when building phone number validation, think about all the formats your users might enter. Consider international prefixes, area codes with varying lengths, and optional delimiters like hyphens, dots, or parentheses. A pattern like \d{3}[-.\s]?\d{3}[-.\s]?\d{4} handles more cases gracefully.

Passwords

Passwords are directly tied to user authentication and security, making them one of the more demanding fields to validate.

Off the top of my head, there are roughly three common conditions — these are baseline security requirements observed across most services:

- Must contain at least one lowercase letter, one uppercase letter, one digit, and one special character.

- No character may repeat three or more times consecutively.

- Must be at least 8 characters long.

Depending on how detailed you want your error messages to be, you might validate these conditions individually or all at once.

The first condition requires that the password contains at least one of each character type. Checking them individually is simple with expressions like /[a-z]/g or /\d/g:

const password = 'test1234!';

// Individual checks

const hasNumberPattern = /\d/g;

const hasLowerCasePattern = /[a-z]/g;

const hasUpperCasePattern = /[A-Z]/g;

const hasSpecialCharPattern = /\W/g;

if (!hasNumberPattern.test(password)) {

console.error('Password must contain at least one number...');

} else if (!hasLowerCasePattern.test(password)) {

console.error('Password must contain at least one lowercase letter...');

} else if (...) {}But the challenge arises when you want to check all conditions at once. A custom group like [a-zA-Z\d] would pass if just one type is present, and a pattern like [a-z]+[A-Z]+ would enforce a specific order — “lowercase must come before uppercase” — which isn’t what we want.

This is where we can use a slightly tricky technique.

Validating with Lookaround

The technique is Positive Lookahead ((?=)), which matches a pattern based on what follows it.

// Match "https" only when followed by "://"

const regex = /https(?=:\/\/)/g;regex.exec('https'); // null

regex.exec('https://'); // ['https']Expressions that match based on what appears before or after a pattern are called “Lookaround,” and they come in four flavors:

| Name | Pattern | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Lookahead | abc(?=123) |

Match abc when followed by 123 |

| Negative Lookahead | abc(?!123) |

Match abc when NOT followed by 123 |

| Positive Lookbehind | (?<=123)abc |

Match abc when preceded by 123 |

| Negative Lookbehind | (?<!123)abc |

Match abc when NOT preceded by 123 |

True to the name “look around,” these expressions check whether a specific pattern exists before or after the target. But by understanding how the regex engine processes them, we can repurpose them to check whether a certain pattern appears at least once anywhere in a string.

Lookaround expressions don’t actually consume characters — they act as boundaries, similar to the \b anchor. The crucial characteristic is that even when the regex engine successfully matches a character via Lookaround, it then acts as if that match never happened.

Let me illustrate with a detailed example. If we apply the expression q(?=u)i to the string quit, the regex engine works like this:

- Engine tries to match

qin the string. The literalqin the regex matches — success.- Engine tries to match

uin the string. Theuinside(?=u)matches — success. Then the engine “forgets” that this Lookaround match ever happened.- Engine now tries to match the pattern after the Lookaround against

uagain.- But the next expression is

i. It doesn’t matchu— failure.

/q(?=u)i/g.exec('quit');nullThis makes sense when you think about it: (?=u) is merely a condition for what should follow q — it’s not actually trying to capture u. That’s why the regex engine tries to match u again with the next expression after the Lookaround.

If we change the literal after (?=u) from i to u, condition 4 passes and we get a match:

/q(?=u)u/g.exec('quit');["qu"]The key insight is that the regex engine treats a Lookaround match as a “preliminary” match rather than a “real” one, so it re-attempts matching the same character with whatever expression comes after the Lookaround.

By exploiting this behavior, we can effectively use Lookaround as an if statement. Let’s use this technique to check one of our password conditions:

Must contain at least one lowercase letter, one uppercase letter, one digit, and one special character.

Checking all at once would make the expression long, so let’s start with just one condition: does the password contain at least one digit?

/(?=\d)./.exec('abc123');["1"]The regex matched 1 because (?=\d) successfully matched 1, and then the engine re-attempted the match on the same character using . — which succeeded.

In pseudocode, it works like this:

if (match(/(?=\d)/, '1')) {

delete(/(?=\d)/); // Pattern matched, discard it

match(/./, '1'); // Re-attempt with the next pattern on the same character

}In other words, the fact that the engine reached the . literal means the preceding (?=\d) already matched that character successfully.

Now that we’ve handled digits, we just chain the remaining conditions — lowercase, uppercase, and special characters — in the same way:

// \d = digit

// [a-z] = lowercase letter

// [A-Z] = uppercase letter

// [\W] = non-word character (not a letter or digit)

/(?=.*\d)(?=.*[a-z])(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*[\W])./gThe \W character class technically matches any non-word character, which includes not just special characters but also characters like CJK or Cyrillic. Listing every special character individually would be tedious, so I’m using the shorthand here. (Laziness is a virtue.) (In production, you’d want to explicitly list the allowed special characters like !@#$%^....)

Using the same approach, we can add the remaining conditions — “no character repeats 3+ times consecutively” and “at least 8 characters” — into a single expression:

/(?=.*\d)(?=.*[a-z])(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*[\W])(?!.*(.)\1{2}).{8,}/| Expression | Meaning |

|---|---|

(?=.*\d) |

Contains at least one \d (digit) |

(?=.*[a-z]) |

Contains at least one [a-z] (lowercase) |

(?=.*[A-Z]) |

Contains at least one [A-Z] (uppercase) |

(?=.*[\W]) |

Contains at least one [\W] (special character) |

(?!.*(.)\1{2}) |

No character repeats 3+ times consecutively |

.{8,} |

At least 8 characters that pass all above conditions |

This expression only reaches the final .{8,} after all the Positive and Negative Lookahead conditions pass, so any string that matches has satisfied every condition we defined.

Of course, validating passwords with a single regex like this means you can only show a generic “Invalid password” error message, so in practice it’s more common to check conditions individually. But Lookaround-based conditional checking is such a useful technique that I thought it was worth explaining in detail.

Extracting Specific Information from Irregular Strings

Most of the time, regex is used for validating user input. But the true raison d’être of regex isn’t merely validation — it’s finding and extracting specific patterns from within irregular data.

This time, I want to share some real-world scenarios I’ve encountered, along with how I used regex to solve them.

Extracting Only Numbers from a String

Extracting just the numbers from a given string is a surprisingly common problem in practice. I’ve frequently needed to pull out numbers representing amounts or ages from source data I couldn’t modify directly, in order to normalize the data or display it in a different format.

For example, imagine an API that returns price information not as a numeric 1000 but as a formatted string like $1,000. And your client needs this business logic:

Which is the larger amount: ”2,000”?

Ideally, the raw data would come as a numeric 1000 and the display formatting would happen on the client side. But modifying the API might require auditing everywhere it’s used and updating every client that consumes it — so sometimes you just leave it as-is for risk management.

In this situation, the developer needs to strip everything except the digits from $1,000, convert it to 1000, and then compare the two amounts.

Without regex, you’d have to split the string, iterate through the resulting array checking whether each character is a digit, or call String.prototype.replace multiple times:

const NUMBERS = ['0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9'];

const amount = '$1,000'

.split('')

.filter(v => NUMBERS.includes(v))

.join('');

// Or

const amount = '$1,000'.replace(',', '').replace('$', '');

console.log(Number(amount));1000The String.prototype.replace approach looks simple enough, but its limitation is that if any unexpected characters sneak in, you need to add another replace for each one. (The moment a string like $1,000...maybe? shows up, you’re in trouble.)

With regex, you can solve the same problem far more concisely and flexibly:

const amount = '$1,000'.replace(/[^0-9]/g, '');

// Or

const amount = '$1,000'.replace(/[^\d]/g, '');

// Or

const amount = '$1,000'.replace(/\D/g, '');

console.log(Number(amount));1000JavaScript’s String.prototype.replace method searches for a pattern and replaces it with the second argument. Since replace supports regex, we can catch “everything that isn’t a digit” and replace it with an empty string — effectively solving our “extract only numbers” problem.

The expressions [^0-9], [^\d], and \D all mean “characters that are not digits,” letting us strip everything non-numeric in one shot.

Of course, you can solve this without regex by combining split, filter, join, and replace. But in the real world, problems far more complex than “find the numbers in a string” are the norm.

Let’s look at a slightly harder problem.

Extracting Monetary Values from a Sentence

This time, we’ll tackle a problem in the same vein but more complex. Instead of extracting digits from a clearly monetary string like $1,000, we need to find and extract monetary values from a long natural-language sentence.

Here’s an example paragraph — drawn from my wishful thinking about getting rich:

The global luxury goods market reached approximately 1,200 per year on luxury items. According to a recent survey, roughly 45% of millennials purchased at least one luxury item, with an average transaction value of 500 billion by 2030.

If we need to extract only the monetary data from this long sentence, we can break the problem into two smaller problems:

- From all the numbers in the text, pick out only the ones that represent monetary values.

- Convert values like

$362 billioninto a numeric362000000000.

The second problem is a bit much for regex alone, so let’s focus on the first: “pick out only the monetary values from all the numbers.”

If we just used \d or [0-9], we’d also catch numbers from 2023, 45%, and 2030 — which aren’t monetary values. So a simple approach won’t cut it.

But the real power of regex shines in situations like this. Even though monetary values seem to appear irregularly in natural language, they actually follow a specific pattern. In English, monetary values are preceded by a currency symbol like $:

Using this observation, we can write a regex to find dollar amounts:

const string = 'The global luxury goods market reached approximately $362 billion in 2023. The average consumer spent around $1,200 per year on luxury items. According to a recent survey, roughly 45% of millennials purchased at least one luxury item, with an average transaction value of $890 per purchase. The market is projected to grow to $500 billion by 2030.';

string.match(/\$[\d,]+(?:\s(?:billion|million|thousand))?/g);["$362 billion", "$1,200", "$890", "$500 billion"]String.prototype.match finds all substrings that match the given regex. Since monetary values appear multiple times in the sentence, match returns all of them.

The regex \$[\d,]+(?:\s(?:billion|million|thousand))? breaks down as:

\$: A literal$sign (escaped because$is a special regex character)

[\d,]+: One or more digits or commas

(?:\s(?:billion|million|thousand))?: Optionally followed by a space and a magnitude word

In the previous post, I covered simple expressions like [^\d]. This time the regex is more complex because we’re dealing with a multi-condition pattern — but the underlying principle is the same. We’re combining character classes, quantifiers, and non-capturing groups to precisely describe the pattern we’re looking for.

Regex is just a tool for finding patterns in strings. Beyond extracting data like this, it can validate user input, parse HTML or JavaScript code, parse file formats — it’s useful virtually everywhere, making it a skill that pays dividends for a long time.

Reformatting Strings

As hinted at in earlier examples, regex is also incredibly useful when you need to transform strings into a specific format.

Think: masking sensitive user information with * characters, or inserting - between digits in a phone or credit card number for readability.

Regex’s capturing feature is particularly effective here. Capturing is useful in many situations, but it truly shines when you need to grab specific parts of a string and replace the rest.

Masking User Information

When building services, you sometimes need to display a list of users while masking their sensitive information. To signal that these are real people (not bots), you typically mask only part of the data rather than all of it.

For names, you might show the first character and mask the rest. For phone numbers, you might reveal the area code and first couple of digits while masking everything else.

function mask (str, headCount = 1) {

// Get the first n characters of the string

const head = new RegExp(`^.{${headCount}}`, 'g').exec(str);

// Mask everything except head

const tails = str.replace(head, '').replace(/./g, '*');

// Combine head and tails

return head + tails;

}mask('Evan Moon', 2);

mask('01012345678', 5);'Ev** ****'

'01012******'The mask function takes the number of characters to leave unmasked as an argument, so we need to construct the regex dynamically using a RegExp object rather than the / literal syntax.

But simple character counting can cause problems in cases like these:

// Spaces count toward the character limit

mask('E Van Moon', 2);

// Hyphens count too

mask('010-1234-5678', 5);// Intended to skip 2 characters, but only 1 is visible

'E ********'

// Intended to skip 5 characters, but only 4 are visible

'010-1********'This technically works, but E V** **** or 010-12**-**** looks much cleaner — excluding spaces and hyphens from the character count improves both completeness and readability.

The tricky part is counting characters while skipping spaces and -. But regex quantifiers count patterns, not individual characters:

// Did the (?:) grouped pattern appear 2 times?

/(?:\S[\s-]*){2}/This expression means: a non-space character (\S) optionally followed by spaces or -, repeated 2 times. For a string like E E-, it groups E\s or E- as a single unit for counting.

Remember: to apply a quantifier to a complex pattern, you need to wrap it in (?:) (Non-Capturing Group) or () (Capturing Group).

Using this property of regex quantifiers, we can easily satisfy both conditions — skip the first n visible characters and exclude spaces/hyphens from the count:

function enhancedMask (str, headCount = 1) {

// Group \S[\s-]* patterns n times and assign to head

const head = new RegExp(`^(?:\\S[\\s-]*){${headCount}}`, 'g').exec(str);

// Mask everything in the tail except spaces and hyphens

const tails = str.replace(head, '').replace(/[^\s-]/g, '*');

// Combine head and tails

return head + tails;

}enhancedMask('E Van Moon', 2);

enhancedMask('010-1234-5678', 5);'E V** ****'

'010-12**-****'Find-and-Replace in Your IDE

Most IDEs and code editors support regex in their Find and Replace features. Since code is essentially a collection of strings with specific patterns, regex can be far more effective than plain text search.

There are many examples of using regex to find and modify code, but let me share a scenario I personally stumble into frequently.

In JavaScript modules, when you export a constant or function without the default keyword, the module evaluates as an object:

export const Test = () => {

return <div>Test</div>;

};import { Test } from 'components/Test';You typically use destructuring assignment to access the value you want. The problem arises when the export style changes mid-development:

const Test = () => {

return <div>Test</div>;

};

// Export style changed

export default Test;import { Test } from 'components/Test';

// Module not found: Error: Cannot resolve 'file' or 'directory'When you’re working fast, it’s easy to change a module’s export style without thinking about all the places that import it. In such cases, you might revert the export, but if the developer intentionally switched to export default, you need to find and update every import statement.

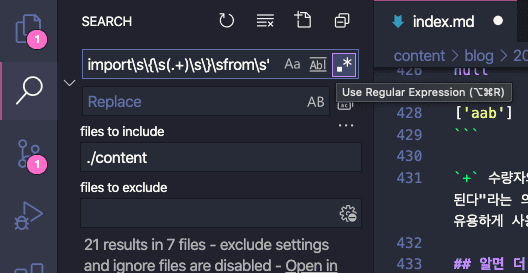

Since most IDEs support regex in Find and Replace, we can handle this quickly:

Regex lets you target exactly the parts you need

Regex lets you target exactly the parts you need

The challenge is that in import { Test } from 'components/Test', parts like import and from 'components/Test' need to stay unchanged. And since we’re only changing the import style, not renaming the variable, we want to keep Test as-is.

// Change this

import { Test } from 'components/Test';

// Into this

import Test from 'components/Test';Regex capturing makes this precise transformation possible — capture exactly the parts you want to keep and replace the rest:

const targetCode = `import { Component } from 'components/Test';`;

targetCode.replace(/\{\s(Component)\s\}/, '$1');`import Component from 'components/Test';`;Using regex for find-and-replace in your IDE really shines during migration work — library upgrades with breaking changes, large-scale refactors, and the like. (In truth, I just make this mistake often enough that it made a good example.)

Wrapping Up

Regular expressions are an abstract tool for matching patterns in strings, which gives them an enormous range of applications.

Beyond the examples in this post, regex can be used to parse files, normalize scraped data, quickly search log files, and much more. Plus, regex syntax barely differs between programming languages, so once you learn it, you’ll keep reaching for it across your entire career.

That’s all for this post on how regex is actually used.