Finding Patterns in Irregularity: A Guide to Regular Expressions

The art of defining patterns in infinite possibility

Developers are people who analyze problems described in natural language, then design and write programs to solve them. This work often involves filtering out the useful bits from a flood of unstructured information, or abstracting haphazardly declared classes and variables into clean structures.

Many skills contribute to doing this well, but one especially important one is the ability to find regularity — patterns — within seemingly irregular information.

Among the most common problems in everyday business contexts are things like parsing files or validating user input: extracting desired information by finding patterns in irregular strings. But the sheer number of edge cases means that trying to solve these with plain programming alone can leave you drowning in a spectacular nest of if statements.

This is exactly the kind of problem that regular expressions — regex — make easy to solve.

What Even Is Regex?

The full name is “regular expression,” but in practice it goes by regex, regexp, or various affectionate nicknames in different developer communities.

Regex is a type of expression that can represent patterns, and by applying these expressions to strings, you can pluck out exactly the parts you want — an incredibly convenient tool. But thanks to its notoriously hostile readability, regex tends to be met with a certain… reluctance.

I use regex fairly often myself, but unless it’s a pattern I write frequently, I always Google the expression and verify it on RegExr before using it.

Memes like this exist because regex genuinely looks like gibberish at first glance

Memes like this exist because regex genuinely looks like gibberish at first glance

But since regex’s primary use case is finding patterns in strings — a situation developers encounter constantly — you’ll inevitably cross paths with regex sooner or later. There’s no escaping it. (Just accept your fate and it gets easier.)

Of course, staring at regex cold makes you think “what on earth does this mean?” But even the longest regular expression is just small expressions combined together, so when you break them apart, they’re often simpler than you’d expect.

Basic Regex Features

Regex has a wide variety of keywords, and the entirety of using regex comes down to combining these keywords to build expressions that capture the patterns you want. In other words, the most fundamental way to get started with regex is to memorize these keywords.

You don’t need to know every keyword — just searching “regex” on Google yields an avalanche of references. But memorizing at least the basics means you can solve simple pattern matching problems without consulting Google, which is a win for productivity. (Memorizing all of them is impossible anyway.)

Combining these features appropriately for each situation is what determines how well you use regex. So in this post, I’ll give a quick taste of the features regex provides, and in the next post, I’ll go deeper with practical, real-world examples.

Character Classes: Catching Groups of Characters

Regex has various keywords that represent specific characters or groups of characters. These are called “character classes.”

Since the core function of regex is finding the characters you want, knowing the types and roles of character classes lets you roughly decipher simple regex patterns without Googling.

Let’s Start by Finding Specific Characters

Regex is packed with character classes like \d and \w whose meanings aren’t obvious at a glance. But these cryptic keywords aren’t the only option. For example, to extract a specific word from a long sentence, you can just write:

'hello, world'.match(/hello/);["hello", index: 0, input: "hello, world", groups: undefined]Since regular characters work freely in regex, keywords like \w and \s that represent character groups must be escaped with \ in front. In other words, \s is a keyword, but s is just the letter s.

Because of this escaping, people unfamiliar with regex often get confused about whether something is s or the whitespace keyword \s. There’s no magic tip here — when you see something like /\/s\.s.{1,2}/, just read it by slicing from left to right, one token at a time.

Using specific characters like hello in a regex can find exact patterns in strings, but if all you need is to find a specific string, you don’t need regex at all — String.prototype methods like includes, indexOf, or search with a plain string argument work just fine.

The real power of regex lies not in finding specific strings, but in finding groups of strings matching a pattern.

Let’s Build Custom Character Groups

Imagine you need to validate that user input contains only English letters. English has 48 characters counting both upper and lowercase, so you could build a map or array of the alphabet and check each character, or in the worst case, chain 48 conditions with ||. (49 including exception handling…)

We can all agree that’s not the coolest approach. And as conditions pile up — checking for numbers too, or verifying that letters repeat n times — the code just keeps getting more complex.

const alphabet = ['a', 'A', 'b', 'B', 'c', 'C', 'd', ..., 'Z'];

const isAlphabet = (string: string) => {

return string

.split('')

.every(char => alphabet.includes(char));

}So regex also lets you create custom groups to catch the characters you want. The syntax is simple: just put the characters you want to group inside square brackets ([]).

// Match x or y or z!

/[xyz]/

// Match anything that's NOT x, y, or z!

/[^xyz]/

// Match a through z!

/[a-z]/

// Match a-z and A-Z!

/[a-zA-Z]/Inside the brackets, you’re not limited to individual characters — you can use - to express character ranges, and adding ^ at the start means “NOT.”

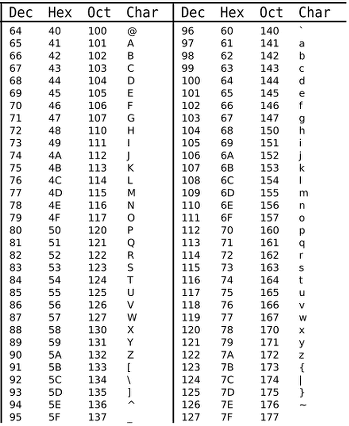

The range syntax like a-z refers to ranges in the ASCII Table.

Looking at the table, you can see special characters like [ and ^ sitting between the uppercase group (65–90) and lowercase group (97–122). Since regex operates based on ASCII codes, if you try to catch only English letters with a range like a-Z, those special characters in between get included too.

That’s why I separate the ranges into a-z and A-Z to filter English letters properly.

With some ASCII knowledge, you can easily build custom character groups using the - range keyword. Even without memorizing the table, just Google “ASCII Table” and reference it.

But manually defining groups every time is also tedious. (Lazier developers make better developers…) So regex helpfully provides several predefined groups.

.

Matches any single character except the newline escape \n. Regardless of what the character is, if it’s a character, it matches. This includes spaces — applying the . class to I am Evan will match spaces too.

// Match the first 4 characters from the start!

'I am Evan'.match(/^..../g);["I am"]To express this character class as a custom group, you’d need to put every character in the ASCII table except \n inside brackets — which is obviously impossible. That’s why knowing these character classes is the first step to writing regex comfortably.

The \d and \D Classes

The d keyword stands for Digit — characters representing numbers. In ASCII terms, this means characters 0–9 (codes 48–57), so characters like Roman numerals (II) or Chinese numerals (五) are not recognized as digits.

Lowercase \d matches digit characters; uppercase \D matches non-digit characters.

'010-1111-1111'.match(/\d/g);// Characters 0-9 are matched, excluding -

["0", "1", "0", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1", "1"]The \w and \W Classes

The w class stands for Word. In regex, “Word” characters are ASCII A–Z (65–90), a–z (97–122), and the \d (digit) group.

Characters outside this ASCII range — like Korean, Cyrillic, etc. — are not considered “Word” and can’t be caught with \w. Like the d class, lowercase \w matches Word characters and uppercase \W matches non-Word characters.

'Phone: 010-0000-1111'.match(/\w/g);// : and - are not Word characters, so only English and digits match

["P", "h", "o", "n", "e", "0", "1", "0", "0", "0", "0", "0", "1", "1", "1", "1"]The \s and \S Classes

The s keyword stands for Space — whitespace characters. Lowercase \s matches whitespace; uppercase \S matches non-whitespace.

'Hi, my name is Evan'.match(/\s/g);// The 4 spaces in the string are matched

[" ", " ", " ", " "]Anchors: Catching Boundaries, Not Characters

The keywords we’ve looked at so far all represent individual characters. But regex also provides the ability to match boundaries between characters, not the characters themselves.

Keywords that catch boundaries are called “anchors.” Since anchors only represent boundaries, they’re typically used in combination with character classes to catch characters positioned before or after a specific boundary.

Since anchors catch the “boundary” itself, using an anchor alone returns a zero-length string.

The ^ and $ Anchors

The ^ anchor represents the start-of-string boundary; $ represents the end-of-string boundary.

// Match only the character right after ^(start boundary)

`Evans Library`.match(/^./);

> ["E", index: 0, input: "Evans Library", groups: undefined]// Match only the character right before $(end boundary)

`Evans Library`.match(/.$/);

> ["y", index: 12, input: "Evans Library", groups: undefined]It goes without saying that a character before ^ or after $ can’t exist, so expressions like .^ or $. can’t match anything.

The \b and \B Anchors

The b keyword stands for Boundary — specifically, all boundaries between words composed of the Word group. In simple terms, it’s a superset of the ^ and $ anchors, which only match the start and end of the entire string.

An important caveat: since it’s about “words composed of the Word group,” this only applies to English letters and digits included in the \w group.

The vague definition of “boundaries between words” might be confusing, but examples make it clear:

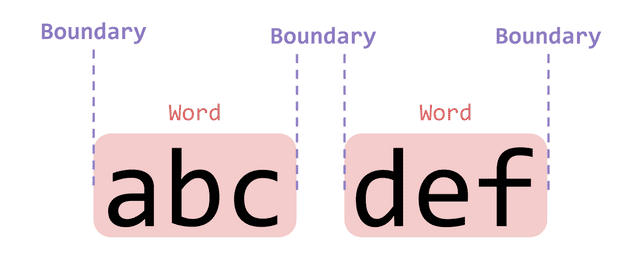

'abc def'.match(/\b/g);["", "", "", ""]Here I used \b to catch all word boundaries in abc def. The results are all zero-length strings, because as I mentioned, a boundary isn’t a character and has no length.

The word boundaries in abc def are:

Don't overthink it — just consider where each word's boundaries are

Don't overthink it — just consider where each word's boundaries are

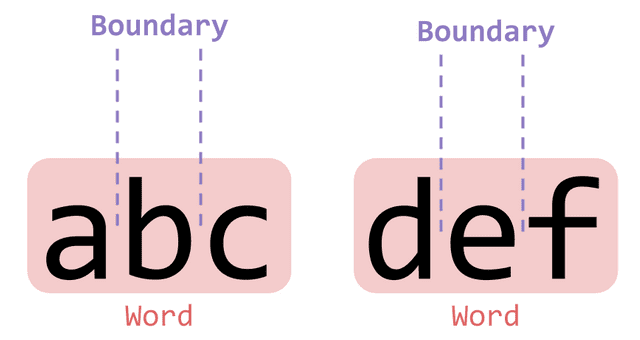

The uppercase \B catches positions that are NOT word boundaries — in other words, positions where a word hasn’t ended.

'abc def'.match(/\B/g);["", "", "", ""]Again 4 boundaries, but their meaning is completely different: these are “boundaries where the word hasn’t ended.”

Boundaries at positions where the word hasn't ended

Boundaries at positions where the word hasn't ended

The b keyword doesn’t match a character — it matches a boundary. Keep this distinction in mind and you’ll find it surprisingly useful in various situations.

Flags: Regex Options

You’ll often see characters like g, i, or m appended after a regex: /regex/g. These are “flags” that serve as option settings.

When using the new RegExp() constructor instead of literal / syntax, pass flags as the second argument.

const regex = /pattern/gi;

const regex2 = new RegExp(/pattern/, 'gi');

// These two have the same pattern

console.log(regex.flags === regex2.flags);trueRegex provides 6 flags: g, i, m, s, u, y. I’ll only cover the three most commonly used — g, i, and m — so Google the rest if you’re curious.

The g Flag

The g flag stands for global. A regex with this flag finds all parts of the string that match the pattern. Without g, the regex only finds the first match.

'hello, world'.match(/./);

'hello, world'.match(/./g);["h", index: 0, input: "hello, world", groups: undefined]

["h", "e", "l", "l", "o", ",", " ", "w", "o", "r", "l", "d"]Without the g flag, regex matches only one character; with it, all matching characters are found. This is intuitive enough that playing with it in the console a few times will make it click.

The i Flag

The i flag stands for ignoreCase — matching without distinguishing uppercase from lowercase.

const regex = /abcd/i;

regex.test('abcd'); // true

regex.test('ABCD'); // trueUser-generated strings often vary in capitalization — My name is Evan, my name is evan, etc. The i flag lets you find the string you want without worrying about case.

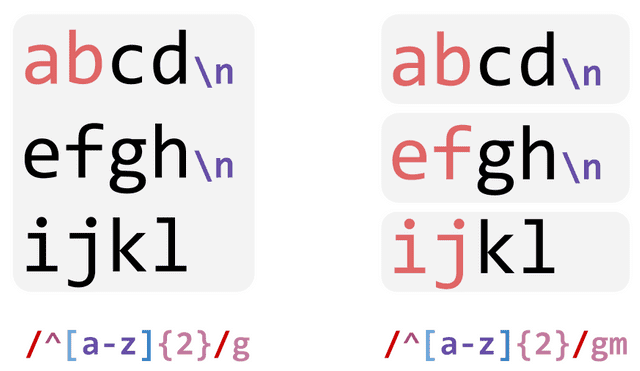

The m Flag

The m flag stands for multiline, meaning the regex will evaluate a multi-line string. But oddly, regex matches multi-line strings just fine without this flag.

Let’s create a multi-line string and try a simple pattern match:

const string = `abcd\nefgh\nijkl`;

string.match(/\w{2}/g);["ab", "cd", "ef", "gh", "ij", "kl"]Regex just finds matching patterns in whatever string it’s given, so multi-line strings work fine without the m flag.

So why does the m flag exist? Because it changes how regex treats the \n newline escape.

Let’s add the ^ anchor to find two characters at the start of the string, not just any two \w characters:

string.match(/^\w{2}/g);["ab"]Only ab is returned. Even though lines are separated by \n, the regex sees the whole thing as a single string, so only the a at the very beginning counts as the start (^).

Now with the m flag:

string.match(/^\w{2}/gm);["ab", "ef", "ij"]Now each line separated by \n is treated as a separate string. The m flag doesn’t simply mean “search multi-line strings” — it means “split on \n and treat each line as its own search target.”

Whether the m flag is present determines if lines are treated

Whether the m flag is present determines if lines are treatedas one combined string or as individual strings.

The m flag is more useful when dealing with long strings containing line breaks than short strings. I’ve used it for things like checking that English text capitalizes the first letter of each line, or parsing uncompressed files.

Quantifiers: How Many Times a Pattern Appears

In the previous example, I used {2} to find two \w characters. This expression specifies the repetition count for the preceding expression. You can also use {0,2} to specify a min/max range.

Expressions that capture how many times a preceding pattern matches are called quantifiers.

Specifying Exact Repetition Counts

'aaaabbbcc'.match(/\w{3}/g);["aaa", "abb", "bcc"]The expression \w{3} simply says “find where the Word group repeats 3 times,” so regex pulls out every 3-character chunk of Word characters.

Repetition patterns are applicable in many situations. A classic example is phone numbers or ID numbers, where character groups repeat a fixed number of times.

'010-0101-0101' // Mobile

'02-0101-0101' // Landline (Seoul area code)

'031-010-0101' // Landline (regional area code)Phone numbers in many countries follow predictable formats. Mobile numbers typically start with a carrier prefix followed by fixed-length digit groups. Using quantifiers makes it easy to capture these patterns:

// Pattern for catching mobile numbers (Korean format)

/01[0|1|6|8|9]-\d{3,4}-\d{4}/;You might wonder why we don’t just match 010 — but mobile carrier prefixes weren’t always 010. Older prefixes like 011, 016, 018 existed before being unified, and some people still use them. Keep edge cases like these in mind when writing validation logic.

Checking If a Pattern Appears One or More Times

Exact repetition counts are great, but they’re too rigid for abstract patterns like “may or may not exist” or “appears n or more times.” So regex provides more flexible quantifiers.

The * Quantifier

The * quantifier matches when the preceding pattern appears 0 or more times. “0 or more” means the pattern before it may not appear at all, or may repeat many times.

// The a before b can be absent or appear many times — match them all!

const regex = /a*b/g;

'b'.match(regex);

'ab'.match(regex);

'aab'.match(regex);['b']

['ab']

['aab']Since patterns before * are matched no matter how many times they appear, any number of as will be caught.

The ? Quantifier

The ? quantifier matches when the preceding pattern appears 0 or 1 times. Unlike *, even if the pattern appears many times, ? only captures one.

// The a before b can be absent or appear many times — only match 1!

const regex = /a?b/g;

'b'.match(regex);

'ab'.match(regex);

'aab'.match(regex);['b']

['ab']

['ab']The + Quantifier

The + quantifier means the preceding pattern must appear at least once. If it doesn’t appear, the match fails.

// The a before b must exist, and match all of them!

const regex = /a+b/g;

'b'.match(regex);

'ab'.match(regex);

'aab'.match(regex);null

['ab']

['aab']Put simply, + means “I don’t care how many times, just be there” — useful for catching characters that must be present.

Nice-to-Know Advanced Features

So far we’ve covered the basics: character classes, anchors, flags, and quantifiers. This is enough for most business situations, but occasionally you’ll hit cases where these alone become unwieldy.

Let’s look at some features that make regex more convenient to work with.

Capturing: Remembering Patterns

Regex doesn’t just match patterns — it can also remember matched patterns. This capturing ability is useful for string replacement (distinguishing parts that should change from parts that shouldn’t), finding duplicates, and more.

For example, consider a string representing a dollar amount: $10000. What pattern captures this?

A dollar amount means $ followed by at least one digit to be meaningful. A simple expression matching $ followed by one or more digits does the trick. (Remember that bare $ is the end-of-string anchor, so escape it with \.)

'$10000'.match(/\$\d+/g);["$10000"]Now, what if we want to change $10000 to 10000 dollars?

You might think of String.prototype.replace, but the pattern above captures $10000 as a whole — there’s no way to keep 10000 while replacing just the $.

We need a way to remember a specific part of the match. This is where capturing comes in.

// Wrap the part you want to remember in parentheses!

/\$(\d+)/The only difference from before is wrapping \d+ in parentheses. This tells regex to capture that part.

The second argument of String.prototype.replace is the replacement string. Captured patterns can be referenced there using the special $n syntax.

'$10000'.replace(/\$(\d+)/, '$1 dollars');"10000 dollars"$1 refers to the first captured group. With multiple capture groups, you can use $2, $3, and so on.

Capturing is also useful for finding repeated characters, since repetition means a previously seen character appears again consecutively:

/(\w)\1/Here I captured a Word character with (\w), then referenced it with \1 — expressing the pattern of repetition.

'aabccdeef'.match(/(\w)\1/g);["aa", "cc", "ee"]Expressions like (.)\1{2} (combined with quantifiers) are useful for password validation rules like “the same character must not repeat 3 or more times.”

Greedy vs. Lazy

Earlier we learned about the + (1 or more) and * (0 or more) quantifiers. Using “n or more” quantifiers creates an ambiguity in pattern matching:

// Find all strings wrapped in < and >!

const regex = /<.*>/g;

"<p>This is p tag</p>".match(regex);["<p>This is p tag</p>"]My regex just says “find anything wrapped in < and >,” so it might seem natural that it captures the entire <p>This is p tag</p>. But <p> and </p> individually also match this pattern.

Regex defaults to matching the longest possible pattern — this is called greedy matching. It greedily gobbles up the longest match it can find. (This is unrelated to the Greedy algorithm concept, despite sharing the name.)

So how do you capture the smaller matches like <p> and </p>?

Make the regex lazy.

// Find all strings wrapped in < and > — lazily!

const regex = /<.*?>/g;

"<p>This is p tag</p>".match(regex);["<p>", "</p>"]The only change is adding ? after the * quantifier. Lazy matching finds the shortest possible matches. Given the same expression, it finds the minimal match and calls it a day — hence “lazy.”

In summary: quantifiers like * and + default to greedy matching (longest possible). Adding ? after them switches to lazy matching (shortest possible).

// Greedy

/<.*>/

/<.+>/

// Lazy

/<.*?>/

/<.+?>/Without understanding the difference between greedy and lazy matching, you’ll fail to capture the patterns you want when multiple valid matches exist. Keep this distinction in mind.

Wrapping Up

I first encountered regex as a college student, building a parser that converted OBJ files into ThreeJS objects. That required seriously heavy regex usage. (The OBJ Loader that ThreeJS provided at the time had a bug 😢)

OBJ files represent vertex coordinates, texture UV mapping coordinates, vertex normals, and more:

# Vertex coordinates

v -1.692615 -0.021714 -1.219301

v 7.334266 -0.021714 -1.219302

v 7.334265 0.021714 -1.219302

...

# Texture UV values

vt 0.0000 0.0000

vt 1.0000 0.0000

...

# Vertex normals

vn -0.0000 -0.0000 -1.0000

vn 0.0000 -1.0000 -0.0000

usemtl Material.001

# Vertex indices for each face

f 1/1/1 4/2/1 3/3/1 2/4/1

f 8/5/2 5/6/2 6/7/2 7/8/2I used the m flag to split the file line by line, then parsed lines starting with v as vertex coordinates, vt as texture UVs, vn as normals, and so on. It was challenging and complex, but fun.

It was eye-opening to realize that computer-generated files are really just sequences of meaningful strings — and even more fun that regex could transform those strings into meaningful information.

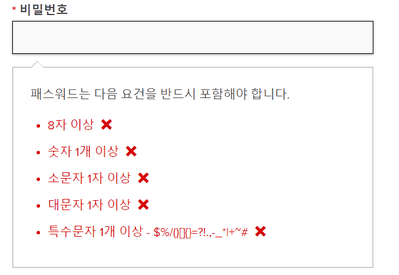

But as I mentioned, regex is used far more often in everyday business logic than in building parsers. For validating user input like passwords or email addresses, regex is practically a cheat code.

You can validate with built-in methods alone, but regex makes it far simpler

You can validate with built-in methods alone, but regex makes it far simpler

Without regex, validating something as simple as an email address requires combining multiple built-in methods — quite inefficient. And personally, as hard as regex is to read, I think it’s still more readable than a complex chain of method calls.

Regex doesn’t have lines or indentation like code, so it looks like a meaningless jumble of characters. But the number of expressions regex provides isn’t that large, and with a bit of practice, anyone can understand short regex patterns quickly.

That’s all for this post on finding patterns in irregularity. In the next post, I’ll walk through real-world examples of how I’ve used regex as a working developer.