Why I Share My Toy Project Experience

What matters more than technical skills? What are we really learning?

I’m part of a team called Lubycon with some friends, and we’ve been running a toy project mentoring program on a volunteer basis. A lot of people ask why we’re doing this without getting paid, and what we’re trying to get out of it. So I wanted to write down my thoughts on that.

Good Developers Need More Than Just Programming Skills

As I’ve said in several previous posts, I believe that being a good developer requires not just hard skills but also soft skills.

Of course, since developers are people who build products through programming, you obviously need a baseline level of programming ability — no getting around that. But the important thing is that organizations don’t just want developers who are good at programming “alone.”

Except in early-stage startups or freelance situations, most developers don’t work alone. Even the most brilliant developer would find it incredibly difficult to design and build massive software entirely by themselves.

That’s why in almost every situation we have to collaborate with others, and that’s where soft skills become important. Unlike hard skills, soft skills aren’t a single specific ability — they’re a collection of capabilities like communication, problem-solving, leadership, and motivation. Basically, everything except hard skills.

Examples of representative soft skills

Examples of representative soft skills[Source] https://www.wikijob.co.uk/content/interview-advice/competencies/soft-skills

No matter how talented a developer is, if they constantly clash with others, tank team morale, can’t communicate effectively, cause drawn-out decision-making, or keep making bad decisions, they’re not going to help the organization grow long-term. That’s why many organizations in the job market are focusing on soft skills too.

So we need to invest effort in honing our soft skills, not just our hard skills.

How Do You Actually Learn Soft Skills?

But the problem is: where do you learn soft skills? Hard skills are domain-specific knowledge, so if you have the research, study, practice, and passion, you can learn them at school, at a bootcamp, or even through self-study. But soft skills aren’t that kind of knowledge.

Plus, soft skills cover almost everything you need at work except hard skills, so they can’t be defined by any one thing.

John Sonmez's "Soft Skills" book covers 70 chapters worth of content — soft skills are vast

John Sonmez's "Soft Skills" book covers 70 chapters worth of content — soft skills are vast

As you can see from representative soft skills like communication, leadership, and time management, soft skills deal with people-to-people issues rather than computer-to-people issues, or with self-management. They’re about handling unexpected situations as they pop up moment by moment.

That’s why these kinds of soft skills are difficult to teach through a fixed curriculum at an educational institution like a bootcamp or school. You ultimately have no choice but to acquire them through diverse experiences, establishing your own methods and values as you go.

Recently emerging bootcamps don’t just follow a curriculum like traditional schools — they combine lectures with collaborative work, creating an environment where students can experience real-world situations ahead of time, almost like a tutorial. This makes bootcamps a really good environment for practicing not just hard skills but soft skills too.

Plus, as the etymology of “bootcamp” suggests, during those few months you’re basically eating, sleeping, and coding — they work you hard.

The term "bootcamp" originally comes from this...

The term "bootcamp" originally comes from this...

But if you’ve looked into bootcamps at all, you know they’re not cheap.

Some bootcamps recently adopted models where students share a percentage of their salary with the bootcamp after getting hired post-graduation. Sure, this doesn’t require job seekers to pay hundreds of thousands upfront, so the economic burden is lighter in that sense. But if you actually calculate the total amount you’ll pay the bootcamp, it’s not a small sum. (Some bootcamps charge up to 20 million won total)

Of course, technical training programs are generally expensive, and I’m sure these prices account for instructor fees, office rental, and various operational costs. But that doesn’t change the fact that it’s not an amount regular folks like us can easily afford.

So does that mean we have no choice but to pay these huge costs to learn soft skills?

Let’s Do Toy Projects with People

Ultimately, bootcamps’ advantage over schools is that knowledge doesn’t just flow one-way from instructor to student. Students communicate and collaborate with each other, practicing both hard skills and soft skills simultaneously.

In that environment, collaborating with people in similar situations lets you stimulate each other and gain soft skills experience. So you could think about it this way:

If I can just create that environment myself, couldn’t I grow without paying hundreds of thousands?

Actually, creating a bootcamp-like environment isn’t that far out of reach. You just need to find like-minded colleagues and work on fun toy projects together.

Sure, if your hard skills like programming or design are weak, it’ll be tough and difficult at first. But if everyone on the team has similar skill levels, the process of studying together and building a product will definitely be a precious experience for everyone.

When I was a college student who knew almost nothing about programming, I self-taught frontend development with only Google as my guide. Our team Lubycon’s first project was obviously a total mess, and development took forever. But we fumbled our way through and somehow managed to release it, and that experience had a huge influence on forming my values as a developer today.

Six years after forming the team, I'm still taking on new challenges with these friends

Six years after forming the team, I'm still taking on new challenges with these friends

Back then, most Lubycon members had no experience building products, so we’d run into tons of problems — scoping work too broadly and making no progress, fighting over minor disagreements, and so on.

But what’s clear is that the experience of bickering through those problems and pushing the project forward has helped me solve the problems I face as a working developer today.

Toy Projects Are a Kind of Test Environment

Most of the problems that arise in toy projects show up similarly when you work at a job. But unlike work, toy projects have lower risk when you fail to solve these problems, and since relationships are more personal than professional, you can focus more comfortably on problem-solving. (Not having economic consequences is a huge win by itself)

When you make decisions at work, you have to consider countless internal and external stakeholders, business needs, legal constraints, and more, so you’re inevitably forced to make constrained decisions. But in toy projects? None of that matters.

Since you’re building the product from scratch anyway, there won’t be users initially, and you’re not making serious money from it, so you can make bolder decisions.

And since most of the time one person handles frontend, one handles backend, and one handles design, compared to work where you need team approval before adopting new tech, toy projects give you a freer environment for technical experimentation.

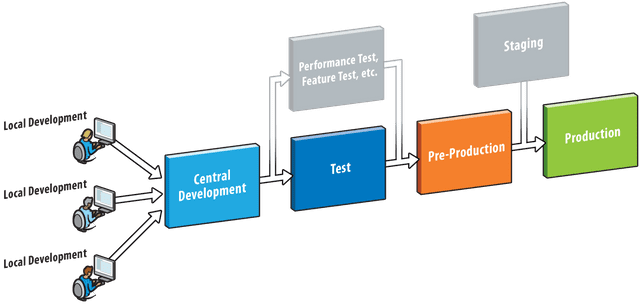

In other words, toy projects create a collaborative environment like working on a team at a job, while simultaneously giving individuals an environment to test challenging decisions and technologies. It’s a kind of test environment.

Just like you control potential risks in test environments before production,

Just like you control potential risks in test environments before production,test methodologies in toy projects before applying them at work

Once you’ve gained enough experience with a new technology through a project and determined it’s a worthy tool, you can propose adopting that tech at your workplace based on that experience.

But It’s Definitely Not Easy

However, no matter how simple the product you’re building, when you actually try it you’ll realize it’s not that simple. You chose toy projects to learn soft skills, but as the project progresses, problems often arise precisely because team members lack soft skills.

Many people worry about their lack of hard skills before starting toy projects, but actually, even if hard skills are lacking, you can somehow study and build a product, so hard skill deficiency surprisingly doesn’t become a big problem for project progress.

Of course, if your hard skills are significantly behind other team members and it’s hindering the project, you obviously need to work your ass off to catch up. But at least you can improve your skills through effort, so it’s not a major constraint.

But when soft skills are lacking, it’s a bit different. As I mentioned, soft skills are learned through experience, so the learning process necessarily involves some trial and error and failure.

The problem isn’t the trial and error itself — it’s that during this process, the group itself is likely to fizzle out.

Plus, unlike work where you get paid, toy projects offer no compensation, meaning members have zero responsibility to the project. It’s 100% dependent on intrinsic motivation.

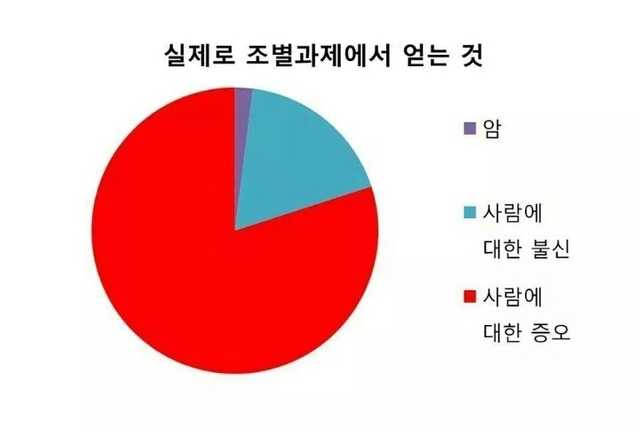

The things that show up in college group project horror stories (which have become a meme at this point) — “dumping all the work on competent people,” “no-show at meetings,” “not finishing assigned tasks” — naturally appear in toy projects too. And unlike group projects where grades prevent you from quitting, people actually leave toy project teams.

Sad but relatable group project meme...

Sad but relatable group project meme...

These problems can seriously damage project progress, but as you can tell from how people bond over group project horror stories, they’re not uncommon.

To keep the group healthy, you need active effort and improvement from members to solve these problems. But since attachment to the team, motivation, and participation rates vary between members, sometimes specific people end up carrying the burden.

I’ll say it again — these experiences are extremely common, so after going through them a few times, most people reach the sad conclusion that “all study groups are like this.”

Problems arising from lack of soft skills have wildly different solutions depending on team member personalities and current circumstances. If you haven’t solved similar problems before, they’re tough to navigate.

Could We Help with This Part?

When I first got my developer job, I didn’t really appreciate how special it was to spend a long time working alongside the same team, studying together and building products.

But as time passed and I met people, heard about their toy projects and study groups, and participated in some myself, I realized that finding a team like this is actually pretty lucky.

And seeing everyone say they envy my ongoing team activities with friends made it clear there’s genuine demand for this kind of experience.

But as I mentioned, many people know from study groups and group projects that consistently running these communities is hard, so they hesitate to even try.

Knowing this, our Lubycon team formed a consensus: why don’t we share the experience we’ve gained over six years solving various team problems with others?

Lubycon wasn’t a mature community from day one either. Each member has different values and working styles, so we’ve fought for hours over how to solve problems, lost all passion when poorly-defined MVPs (Minimum Viable Products) dragged development out too long, had work pile up on specific people, and even had members leave. Every problem that happens in other communities has happened in Lubycon too — and still happens now.

But over about six years, going through these various problems, we’ve gradually learned how to solve them together. That’s why we want to share these problem-solving experiences with others.

That’s why the mentoring project I’m currently running isn’t about development or design — it focuses purely on soft skills like communication, collaboration methodologies, and even individual time management.

Of course, I’m not some great person who’s qualified to teach anyone. But running this blog, I’ve experienced how knowledge and experiences I thought were trivial can be hugely helpful to others. That’s why I think this mentoring itself has great meaning.

Wrapping Up

Over the past six years since college, I’ve had the lucky opportunity to grow with good friends in a team called Lubycon. I can casually suggest working together on weekends, and when I want to try new tech using our pooled funds, they readily say okay. Having this team lets me take on exciting challenges with these people every day.

Right now we’re in a modest situation with only 4-5 mentors, reaching about 20 people per cycle. But I have this happy fantasy that if people who gained good experiences through our mentoring pass those experiences to others, someday more people might have experiences like mine. (Now that I write this, it sounds kind of like a pyramid scheme…)

That’s all for this post on why I share my toy project experience.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Are Non-CS Major Developers Really at a Disadvantage?

EssayHow to Find Your Own Color – Setting a Direction for Growth

Essay2020, How Did I Grow? A Mid-Level Developer's Retrospective

EssayMigrating from Hexo to Gatsby

Programming/TutorialsCan I Really Say I Know Frontend?

Essay