Deep Dive into GTM: Google Tag Manager

Can you manage events without developers? The world of Google Tag Manager

Google Tag Manager, commonly known as GTM, is an event tracking solution Google launched in 2012 for managing various tags — web analytics, ad performance measurement, affiliate marketing tracking — through an internet interface.

At my previous job, I used event tracking solutions like Google Analytics and Segment. While these tools worked fine for collecting user behavior data, their disadvantage was clear: whenever a PM or marketer wanted to track additional behavior data, they had to ask developers to add code.

But with GTM, the amount of code developers need to write for defining and sending events drops significantly. PMs and marketers can use GTM’s management interface to directly define events and even determine when to send them. Plus, since event logging code unrelated to business logic doesn’t get mixed into your application code, it’s a win for developers too — a tool that benefits everyone.

Honestly, not having to add event logs is already a huge win for developers

Honestly, not having to add event logs is already a huge win for developers

However, even when using GTM to define events, this work isn’t entirely unrelated to programming. Sure, GTM’s basic features make it fairly easy to define and send simple events, but if you want to create events that handle slightly more complex situations, you’ll need some understanding of programming concepts like variables and triggers. (Some posts claim you don’t really “use GTM” until you understand the Data Layer)

So this post isn’t just for developers — it focuses on helping non-dev roles like PMs and marketers who collaborate with developers understand the minimum programming knowledge needed to use GTM effectively. If you’re a developer looking to introduce GTM to your organization, reading this with an eye toward how to explain these concepts more clearly to non-developers might be worthwhile.

Prerequisites for Using GTM Freely

You should have at least some understanding of what HTML, CSS, and JavaScript do in a web client environment. Sure, you can use GTM without this knowledge, but you’ll face some constraints when trying to send events with precise timing and specific values.

For example, imagine a user clicking a specific button. First, you need to know that the user clicked that “specific button.” GTM provides a feature using CSS selectors to distinguish this specific button — but without knowledge of CSS selectors, you’d only be able to attach click events to “all buttons.”

Or consider that nowadays many sites use SPA (Single Page Application) approaches that render by swapping page content with JavaScript. Without understanding browser History, using only the “page view” trigger might fail to properly detect page changes.

That’s why, if you lack this knowledge while reading this post, you might struggle to grasp what I’m explaining. If that’s your situation, I recommend checking out Web courses on OpenTutorials before continuing.

How GTM Works

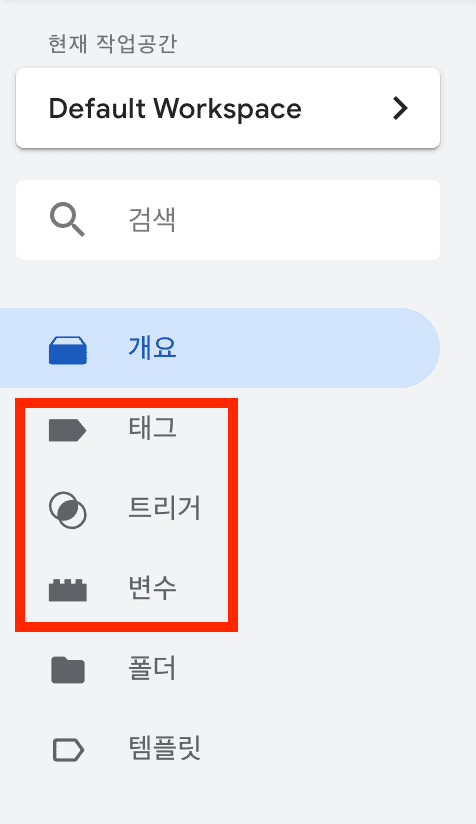

GTM lets you use “tags” to define event types, “triggers” to define when to send events, and “variables” to define the data included in events.

Of course, developers already know concepts like triggers and variables, but for non-developers, these concepts might not feel intuitive. So while explaining each trigger and variable type, I’ll also gradually explain what they actually mean.

Understanding these 3 keywords is understanding GTM itself

Understanding these 3 keywords is understanding GTM itself

Before diving into tags, triggers, and variables, we need to understand what it’s like without GTM.

Without tools like GTM, people who need data — PMs, data analysts, marketers — would define events, and developers would add event-sending logic to the application’s source code.

function login (loginData: LoginData) {

try {

// Login communication and data parsing

const response = await fetch('/login', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify(loginData),

});

const user = await response.json();

// Send Google Analytics login success event

gtag('event', 'login', { userId: user.id });

return user;

} catch (e) {

// Exception handling for login failure

}

}Even if you can’t read code, that’s fine. The only important part in this code is the single line gtag('event', 'login', { userId: user.id });. I used this code to tell Google Analytics that a login event occurred and what the logged-in user’s ID is.

Sure, having developers write code to directly send events doesn’t cause problems, but developers struggle with managing event code unrelated to business logic, (it’s annoying) while roles that actually need the data — PMs, marketers, data analysts — can do nothing but wait for developers to add the code.

That’s why GTM uses concepts like tags, triggers, and variables to let non-developers easily define events using GTM’s management interface.

When using code to send events, you don’t need to explicitly separate tags, variables, and triggers — the program flow determines everything. But GTM assumes events are managed separately from program flow, so it clearly distinguishes these concepts.

Tags

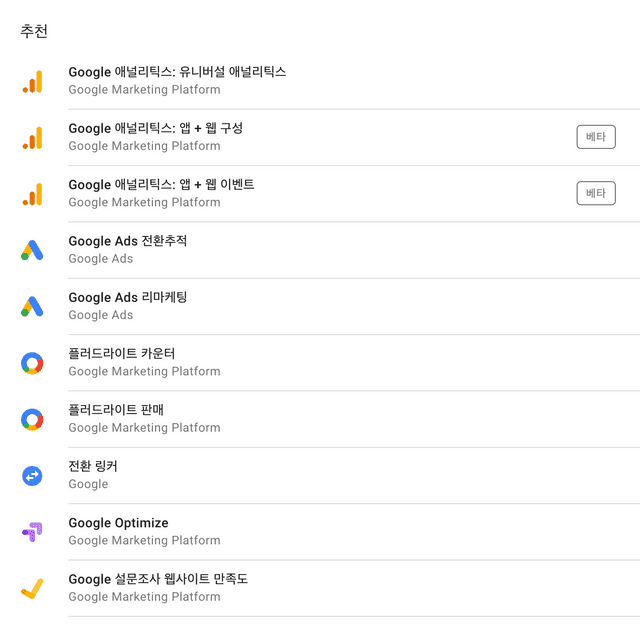

Tags are JavaScript code that sends information to third parties like Google… though actually, tags are similar to what we generally call events.

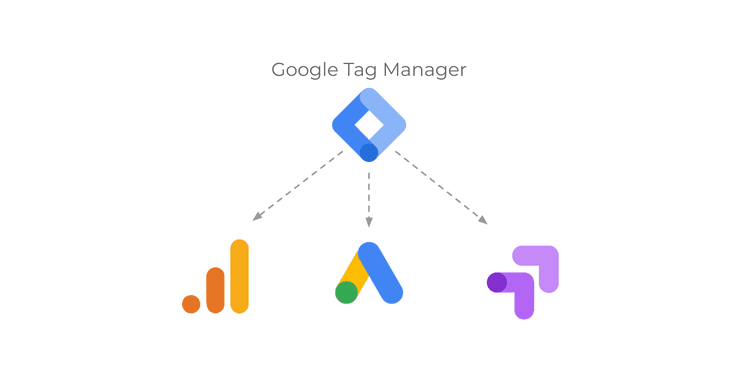

Fundamentally, GTM isn’t an event tracking solution — it’s an event tracking “management” solution. GTM doesn’t directly receive and store events on a server. GTM acts as a broker that borrows and relays events from other solutions like Google Analytics connected to GTM.

Supports various external solutions, but Google products are naturally recommended...

Supports various external solutions, but Google products are naturally recommended...

The concept that determines “what to include” in these other solutions’ events is the “tag.” In other words, a GTM tag could become a Google Analytics event, a Criteo tag, or a Hotjar tracking event.

Triggers

“Trigger” literally translates to “trigger” or “firing mechanism.” Just like the name suggests, a trigger acts as the firing pin that determines when to fire the bullet called a tag.

The moment you pull the trigger could be when a user clicks a signup button, when a product sales page opens, or even when a user scrolls down and sees a newly added banner.

Actually, people who work with data professionally understand when to send specific events better than developers like me, so I won’t explain deeply.

GTM supports quite a variety of trigger types. Naturally, the more precisely you understand what these triggers mean, the more diverse and detailed timing you can achieve for sending events, so let’s go through them.

Pageview

Page View

The Page View trigger fires right when the web browser starts loading the page. For developers: resources haven’t fully loaded yet, so users can’t see the page content, but the connection to the page’s server has been established and resource loading has begun.

DOM Ready

This trigger fires when the browser completes rendering the page’s DOM. So if a tag needs to interact with the DOM, this trigger is better.

Window Loaded

This trigger fires when all resources needed for the page have fully loaded. Users are likely seeing the page’s proper UI.

Click

Just Links

As the name says, this trigger fires only when links are clicked. It offers a “tag waiting” option — when users click a link, it sends the tag before navigating them to the next page.

The reason is that if the page navigates before sending the tag, the tag-sending action itself risks being voided. On the flip side, users might experience a slight delay waiting for the tag to send before page navigation, which isn’t great for UX.

All Elements

This trigger fires when any element is clicked, which naturally includes links.

User Engagement

Scroll Depth

This trigger fires when users scroll past a certain percentage of the total page. Vertical scroll depth uses downward scrolling as the baseline, horizontal scroll depth uses rightward scrolling. Depth can be specified as a percentage or pixels.

Form Submission

This trigger fires when a Submit event occurs on a Form element on the page.

Note that this trigger has caveats: Form elements might not be used, or even if they are, developers sometimes cancel the Submit event because Form element Submit events force browser refresh.

If you want to use this trigger, I recommend asking developers first how data is being submitted to the server on that page.

Element Visibility

Element visibility fires when an element appears on screen. “Appears on screen” could mean the element entered the viewport through scrolling, or it could mean a conditionally visible element (like a toggle) became visible.

Beyond visibility criteria for each element, GTM provides “trigger firing timing” functionality to specify whether to fire the trigger every time the element appears or only the first time.

Other

History Change

Triggers based on history change events fire when the URL hash changes or when the site uses the HTML5 History API’s pushState method. For example, this trigger is useful for executing tags that track virtual pageviews in SPA applications.

In other words, whether the page actually navigates or not, if browser history is touched, this trigger fires.

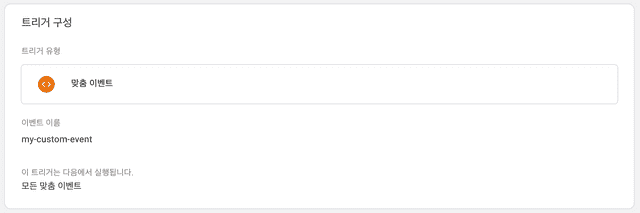

Custom Event

As I’ll explain below, GTM monitors a JavaScript global variable called dataLayer and fires triggers or assigns variable values by detecting data entering this variable.

As shown above, if you define a custom event named my-custom-event in GTM’s management interface, GTM watches the dataLayer array for the value event: my-custom-event and fires the trigger when it arrives.

In other words, when you want to fire triggers for complex or special situations that GTM doesn’t provide by default, you can freely fire triggers from code.

const dataLayer = [];

// Fire trigger

dataLayer.push({ event: 'my-custom-event' });Sure, using the dataLayer array to fire triggers or assign variable values still requires developers to add code. But compared to other event solutions, the code is minimal and the trigger-firing method is simple, making it easy to manage.(Except for having to use global variables…)

Variables

A variable is literally a number or value that can change. Variables consist of a name (Key) and value (Value), and GTM constantly monitors these variables. Variables can be used to control when triggers fire, or to store values that need to be used repeatedly within GTM.

For example, the former might be “send an event only if the user who clicked this button has ID 1!” The latter might mean storing ID values provided by Google Analytics or Google AdWords.

Navigation

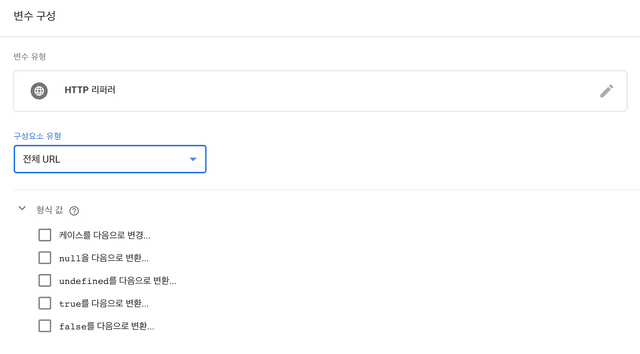

HTTP Referrer

Returns the HTTP referrer. It’s easiest to think of referrer as “previous page address.” Referrer can be an extremely important value for marketers driving user inflow through various ad channels, as it’s the clearest indicator of which ad channel brought users to our service. Note that this uses the value from document.referrer.

GTM’s component type menu lets you select detailed options like whether to fetch the full URL or just the path.

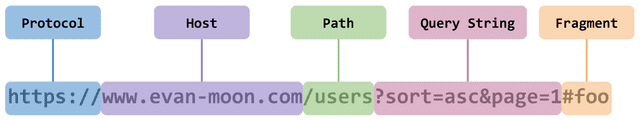

For non-developers, a quick explanation: URLs are composed of several components as shown below. These components each carry different information, and collectively they’re called a URL or URI.

If you don’t need the full URL and only need specific information within it, I recommend filtering data using the component type menu.

URL

Returns the current page’s URL. Like referrer, you can filter to get desired values using the component type menu.

Page Variables

1st-Party Cookie

Returns the value of a cookie whose name matches from the domain the user is on. Cookies are small text files stored in browsers.

console.log(document.cookie);ThVbdUg.; APISID=Twvmlsi3NXZBQQKv/AfV5gB9toKeSC3cui; SAPISID=qcBt_OBeNnbuq1sG/AuZto1M1fXt3YRBoD; __Secure-APISID=Twvmlsi3NXZBQQKv/AfV5gB9toKeSC3cui; __Secure-3PAPISID=qcBt_OBeNnbuq1sG/AuZto1M1fXt3YRBoD; PREF=al=ko&f6=400&f4=4000000; wide=1; SIDCC=AJi4QfFq_T4Wv10c3rnS-qZdLNrXY_FS-TQVBAdC6uD4uTmYU0xW3lCfJd4DcJqMecClwMXWbQCookies are strings formatted as key=value;key2=value2;. Since browsers manage them as text files, values aren’t deleted even when users close browsers. That’s why cookies are frequently used to manage state that must persist regardless of browser closure, like “Don’t show this for 3 days.”

Also, since cookies are stored in browsers themselves, each site’s cookies have domain values to prevent mixing. If a cookie has domain evan.com, sites like dev.evan.com and www.evan.com are recognized as the same site and share the cookie. But if the cookie’s domain is dev.evan.com with a subdomain, www.evan.com is recognized as a different site and can’t use it.

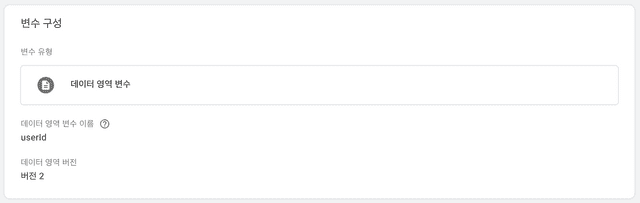

Data Layer Variable

This variable can be assigned values dynamically using the dataLayer I mentioned when explaining custom event triggers. GTM treats this variable specially, so developers must manually declare it as a global variable in code and initialize it.

Then in code, use the push method to input data into this array. Based on the input key, GTM finds the value and uses it as a data layer variable. Words alone make it hard to understand, so let’s see an example.

First, create a data layer variable in GTM’s management interface and set the data layer variable name to userId.

In other words, this variable just created in GTM’s management interface means “use the variable when data with the userId key enters the dataLayer array declared in code.” To assign a value to this variable, put an object with a key matching the variable name into the dataLayer array in code, like { userId: 1 }.

const dataLayer = [];

dataLayer.push({

userId: 1234,

});Now you can include this assigned variable in events, or detect when this variable gets assigned to fire triggers.

Custom JavaScript

The variable’s value is set to the result of a JavaScript function. The JavaScript function used here must be an anonymous function that returns a value.

This variable directly uses the function execution result, so you can use programming features like conditionals and loops as-is — which is its advantage.

For example, if you want to report the time a user clicked an element as an ISO format string like 2020-04-11T07:56, you’d write custom JavaScript like this:

function () {

const now = new Date();

return now.toISOString();

}Since this JavaScript code ultimately gets inserted into and executed in your application, if your application has global variables, you can access them.

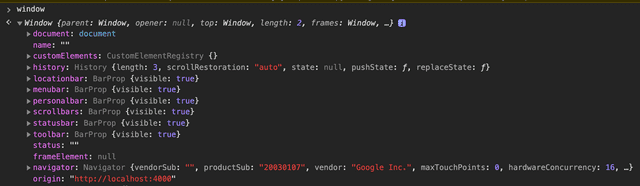

JavaScript Variable

Simply takes a JavaScript global variable declared in the application and uses it as a GTM variable.

Even if you don’t understand global variables, that’s fine. There’s a simple way to discover global variables. First, visit your application, open browser developer tools, type window in the console, and hit enter — you’ll see data like this:

Ta-da. The naked Window object exposed

Ta-da. The naked Window object exposed

JavaScript global variables are designed to always live in the global window object. In other words, the values that appear when you print window object contents in the console are the global variables you can use in GTM.

Page Elements

Element Visibility

Gets whether an element is visible on screen. In other words, whether the element is currently displayed or not.

You can select elements using ID or CSS selector, but if you use CSS selectors, multiple elements might be selected simultaneously — in which case only the first element is retrieved.

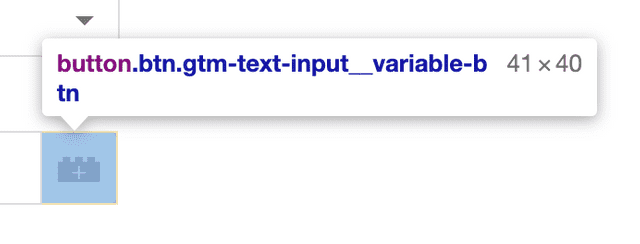

Even if you’re not a developer, you can easily discover which DOM element you want. In Google Chrome, position your mouse over the element you want to know about, right-click to see tools, click the “Inspect” menu, and developer tools will open with your inspected element automatically selected.

The button.btn.gtm-text-input__variable-btn shown as a tooltip over the element is the CSS selector. But as I mentioned, CSS selectors aren’t unique IDs. The same selector can select multiple elements, so using IDs is better. Elements with IDs will have CSS selectors starting with #, like #foo.

Output type can be true/false or percentage. When selecting true/false, you can set a minimum percentage that determines how much of the element must be visible to count as “visible.”

Note that this minimum percentage value isn’t transparency — it’s how much of the element is on screen. In other words, if half is cut off, it’s 50%.

DOM Element

The value is set to the text of a DOM element or the value of a specified DOM element attribute. If an optional attribute name is set, the value specified in the attribute is returned in the variable’s value. Otherwise, the text within the DOM element becomes the variable’s value.

A DOM element is basically the structure you write using HTML. Here’s a simple example:

<div>

<span id="foo">Hi!</span>

<button id="button" data-type="submit">Submit</button>

</div>If I specified a DOM element variable as the #foo element in GTM’s management interface, the variable’s value would be the text the span element holds: Hi! But if I specified the DOM element variable as #button and entered data-type in the attribute name field, the variable’s value would be submit.

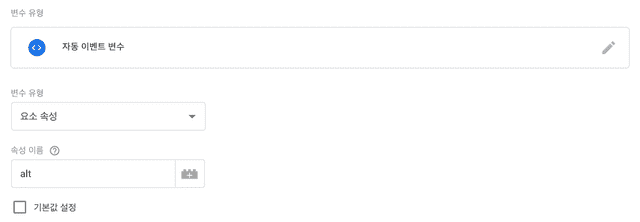

Auto-Event Variable

Auto-event variables automatically collect element-related information when events occur through triggers related to HTML elements, like clicks or element visibility.

Imagine you want to know exactly which image a user clicked when they clicked an img element.

<img src="/static/test.png" alt="Test image" />We can use a click trigger to know the user clicked that image, but unless we put the image itself in a variable, we have no way of knowing which image the user clicked. That’s where we can use the alt attribute.

The alt attribute is alternate text displayed if the image doesn’t load. Also, for people who can’t see images (like visually impaired users), computers can convert this text to speech and read it aloud. That’s why web standards recommend always using the alt attribute with img elements.

In other words, since the alt attribute should contain text that well describes “what this image is,” we can indirectly know which image the user saw and clicked through that attribute’s text.

Auto-event variables are designed to automatically collect element information when HTML element-related triggers fire, making them extremely useful in these situations.

Automatically fetch the value held by the `alt` element attribute!

Automatically fetch the value held by the `alt` element attribute!

This variable can be applied in various scenarios beyond this — fetching a form’s ID when a form element is submitted, getting link text or target URL when a link is clicked. If you have some knowledge of how HTML is written, like semantic markup, this variable has extremely high utility.

Utilities

Custom Event

The custom event variable relates to the custom event trigger I explained in the trigger section. As explained, custom event triggers fire when an object with the event key enters the dataLayer array. The custom event variable is automatically assigned to that event’s name.

// Fire trigger

dataLayer.push({ event: 'my-custom-event' });Custom Event Variable: my-custom-eventConstant

Unlike variables (which imply changeability), constants are unchanging values. When using external solutions like Google Analytics or Criteo, each account issues authentication keys — these keys are often registered as GTM constants for convenient management.

Random Number

Literally a utility variable that assigns a random number between 0 and 2,147,483,647 to the variable each time.

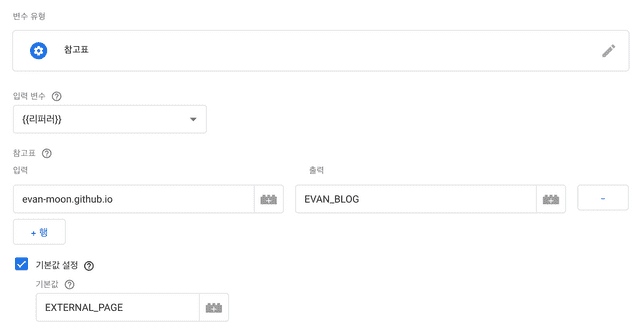

Lookup Table

A lookup table outputs specific values if a specified input variable matches conditions entered in the lookup table. In other words, if the input variable contains a string in the table’s input column, it returns the value in the output column — think of it as a table containing conditionals.

The “referrer” value I selected as the input variable contains which page the user was on before entering my blog. Using the lookup table, I’ve set it so if the referrer contains the string evan-moon.github.io, it puts EVAN_BLOG in this variable, otherwise it uses EXTERNAL_PAGE as the default value.

You could add another row with google.com in the input and GOOGLE in the output.

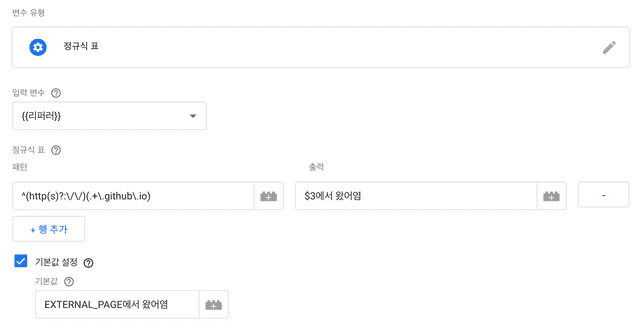

Regex Table

A regex table is identical to a lookup table — it returns specific output values when the input variable matches conditions in the regex table’s input column. But regex tables let you use regular expressions, which are great tools for string manipulation, providing much more powerful functionality than lookup tables that can only check for substring inclusion.

Usage is identical to lookup tables, but the regex table’s input column takes regular expressions instead of simple strings.

This variable I just created takes referrer as the input variable, and if the referrer matches the regex ^(http(s)?:\/\/)(.+\.github\.io), it returns the value Came from OOO.

In other words, if the referrer is my blog https://evan-moon.github.io, it returns Came from evan-moon.github.io. Like this, compared to lookup tables that can only check substring inclusion, regex tables can use regular expressions for more precise string checking plus capturing functionality, making the application range much broader.

If you want to debug how your created regex table works, you can directly use regular expressions to replace strings in the browser console.

const regex = /^(http(s)?:\/\/)(.+\.github\.io)/;

'https://evan-moon.github.io'.replace(regex, 'Came from $3');'Came from evan-moon.github.io'Of course, regular expressions as a language are hard to read and have diverse functionality, making the learning curve steeper than other programming languages. For non-developers, it might feel like a big barrier. But regex tables have much higher flexibility and enable more diverse applications than lookup tables, so I recommend anyone interested in string manipulation study regular expressions. (Actually, regex-hyung has a bad reputation even among developers)

Wrapping Up

GTM is a solution that helps non-developers with direct event log needs define events and send timing directly, without developers managing event logs in business code.

But ironically, utilizing GTM 100% requires some programming knowledge. I wrote this post hoping non-developers could gain the minimum knowledge needed to leverage GTM.

Of course, it’s disappointing that I only briefly mentioned the programming knowledge needed for GTM with short explanations. But if I explained JavaScript global variables, CSS selectors, HTML History, etc. in detail in this post, it would no longer be a post — it would be a book. Please understand.

If you’re a developer who proposed introducing GTM to your team, you have at least a minimal responsibility to help non-developer teammates adapt to GTM. It would be good to think about how to explain each variable’s and trigger’s characteristics and uses so non-developer teammates can understand them well.

That’s all for this deep dive into GTM, Google Tag Manager.