Question Driven Thinking — Learning by Asking Yourself Questions

A learning method more powerful than Googling: the habit of questioning

Think back to when you first learned programming. Most people learned from someone — in a school, a bootcamp, or a course — because the path of self-teaching is too long and treacherous for a complete beginner.

But once the beginner phase is over and you’ve landed a job as a developer, things change. There’s no teacher anymore. You’re on your own to grow your skills. People suddenly thrust into this environment feel the same overwhelming helplessness they felt when they first started programming.

You can grab a coworker and ask questions, but that only lasts so long. Keep asking similar-level questions and all you’ll get back is RTFM (Read The Fucking Manual) or a cold suggestion to just Google it. But when you try Googling, you don’t even know what keywords to search for.

Every developer has been through this, I think. A mountain of things to learn, but no idea where to start or how to study. Nobody is kindly laying out a curriculum for you. In the end, you have to find, filter, and digest information on your own.

Let’s Look at Reality First

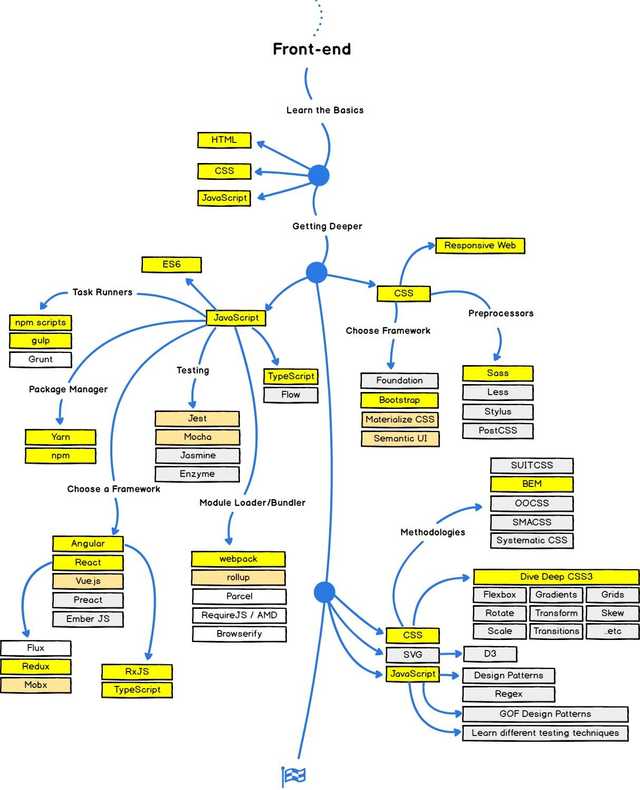

Before diving into the main topic, let’s pin down what this “overwhelming feeling” actually is. It’s not hard to conjure up. I’m a frontend developer, so let’s imagine a situation where I need to build a simple web frontend application.

First, you need to pick a library or framework that connects your view and model to render the UI. The big names are React, Vue, and Angular. Most people go with React since it has the largest ecosystem, but honestly, you can build whatever you need with any of them.

Modern web applications demand complex client-side state management, so you’ll also need to choose a state management library. The popular ones are Redux and MobX — pick your flavor. If you chose Vue as your UI framework, just use Vuex for the sake of your mental health.

If you need to manage complex object state, immutability helpers like ImmutableJS or Immer would be nice to have.

If you’re using Redux, you’ll also need to pick an async middleware — redux-thunk, redux-saga, and the like. Or how about RxJS, which has been gaining traction lately? It even comes as a Redux middleware via redux-observable.

For package management, choose between npm or yarn. For unit testing, Mocha or Jest. For your eslint config, pick airbnb or standard and customize to taste.

Oh, and come to think of it, using TypeScript instead of plain JavaScript might not be a bad idea — since we’re building this, might as well make it robust. In that case, we need to check whether all those libraries above support TypeScript.

I thought we were building a "simple" application...?

I thought we were building a "simple" application...?

All those tools I just rattled off aren’t me showing off — they’re things frontend developers actually deliberate over every time they start a project at work or on the side. None of them are strictly required, but once you learn them, they boost productivity so much that most frontend developers use some combination of them.

And to actually use these tools properly, you also need knowledge of JavaScript internals like closures and the event loop, virtual DOM, data binding, MVVM patterns, Flux patterns, functional programming, and more.

There’s been an explosion of new things in frontend lately, but developers in other specializations face a similarly large body of knowledge. It’s just specialized differently for each discipline.

The point of this long preamble is really just one thing:

“Nobody can kindly teach you all of this.”

You Have to Find Information Yourself

Does anyone exist who could teach you all of that? Personally, I don’t think so.

If programming were like mathematics — where a formula created 100 years ago is still used 100 years later — then maybe someone could build a systematic curriculum covering everything. But many of the tools I mentioned might not even exist next year. The lifespan of this knowledge is extremely short.

And it’s hard to say which of these overlapping tools is “better” or “worse.” Go ask a nearby frontend developer “Is React better or Vue?” What do you think they’ll say? Probably that both are good, both are bad, or they’ll just pick their favorite.

For these reasons, programming is a field where building a specific curriculum is quite difficult. Sure, you can create a curriculum for absolute beginners, but beyond that, curricula become somewhat pointless.

Imagine spending three months at a bootcamp diligently learning Vue, only to join a company that uses React. You can’t exactly ask the company for time off to go learn React for another three months.

In the end, developers have no choice but to get comfortable finding and learning information on their own, tailored to their organization’s needs and the technologies they want to explore. That’s why “just Google it” is the answer to so many developer questions.

But actively learning by finding information on Google and Stack Overflow requires the ability to choose effective search keywords and the discernment to distinguish good information from bad — which makes it harder than it sounds. (You also need decent English.) And nobody can teach you this; you have to practice and figure it out yourself.

But since I can’t just tell someone to “go Google things” when they don’t even know what to search for or what to study, let me share a very simple method I use frequently.

All Keywords Are Connected

When we study, we typically “memorize.” Memorization-based learning allows us to quickly absorb narrow pieces of information, making it a pretty good fit for developers who are constantly chasing new trends.

You know — memorizing the four characteristics of pure functions, or the features and trade-offs of TCP vs. UDP. Or when a new library or framework comes out, skimming the docs and coding along is also a form of memorization.

But while memorization is fast, it has a downside: keyword acquisition is fragmented. By “fragmented,” I mean that learning one keyword doesn’t naturally lead you to the next. If you’ve studied this way, you’ve probably had this thought at some point:

Okay... I've got this part down... but what do I study next...?

Okay... I've got this part down... but what do I study next...?

You know intellectually that what you’ve learned is nowhere near enough, but you don’t know what to study next. And studying something completely unrelated feels like you’re just poking around randomly. This happens because the knowledge acquired through simple memorization isn’t “connected.”

Knowledge is essentially a keyword mind map, where every keyword is linked to other closely related keywords. Active learning is really a continuous process of exploration — finding and following these connections.

Memorization-based learning means manually discovering and studying each keyword on the map one by one. But finding all those keywords on your own is hard. So we need a method that naturally leads us from one keyword to the next while studying.

And when you repeatedly learn one keyword and discover the next, the fragmented pieces of information you’d stored through memorization naturally form connections between each other — making them stick longer. Two birds with one stone.

So how do you find connected keywords?

Ask Yourself Questions

One reason we fail to discover related keywords while studying a topic is that we simply accept pre-organized knowledge through memorization. If you just memorize “A is B,” you miss the opportunity to find other keywords hiding within that statement.

The method I’m proposing is “questioning.” But not questioning others — questioning yourself. (Save asking others as a last resort.)

Ask yourself things like “Why does this work this way?” and “How is this possible?” while studying. Find out what you don’t know about the keyword you’re studying, one piece at a time. Once you know what you don’t know, you can Google for the answer. Repeat this a few times and you’ll discover a new keyword that holds the answer to your question.

Let me use React’s useState hook as an example. React’s useState is a hook used to store and remember state in functional components.

function Foo () {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<>

<div>{count}</div>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count++)}>+</button>

</>

);

}Knowing that useState lets you manage state in functional components is perfectly sufficient for writing code and building applications. If you’re learning under time pressure, you can stop here and start coding. But if knowing that useState exists isn’t enough to satisfy you, this is where you should throw out a new question.

When I first encountered React’s functional components and learned about this hook, I had this very basic curiosity:

How does the

useStatehook store state?

This isn’t some profound question. It’s just taking one small step of curiosity beyond the simple memorization of ”useState lets you store state in functional components.”

Someone with deep JavaScript knowledge might have had a more advanced question right away, but at the time, I had zero intuition about how the hook worked internally.

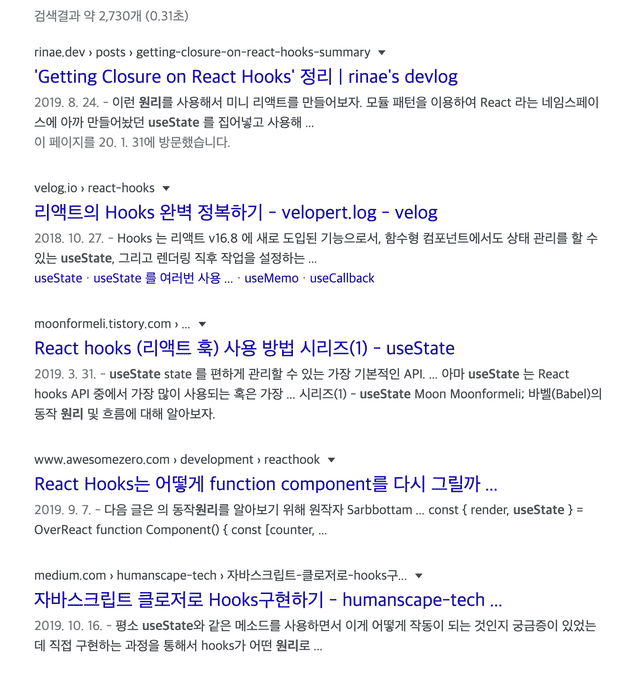

Anyway — you’ve asked yourself a question, so now you need to find the answer. There’s no teacher beside you, so let’s just search this question on Google as-is.

My search query: “how does useState work.” Search keywords aren’t a paid resource — just type whatever comes to mind. There’s no special skill required for Googling.

The Google gods know all things

The Google gods know all things

Searching this keyword, I can already see detailed posts where others have explained React hooks. If searching in your native language doesn’t yield results, try an English query like “principle of useState” — you’ll almost always find what you need. The gap in available information between searching in English versus other languages is enormous, so it’s worth building the habit of searching in English.

React’s useState hook actually uses JavaScript closures to store state within a function. With a bit of searching, you’ll discover the keyword “closure.”

Once you’ve found this new keyword, if you already know what closures are, you might try implementing useState from scratch as a learning exercise. If not, search for “JavaScript closures” and study up. While studying closures, you’ll probably find another question to ask, which will lead you to yet another keyword deeper down.

Some readers might think, “I can barely keep up with learning and using things as-is — when am I supposed to understand the underlying principles?” But there’s an important distinction between “the ability to understand a keyword” and “the ability to find a keyword.”

The ability to understand a keyword quickly can’t be developed in a short time with a few tips. It requires a baseline level of domain knowledge.

But “the ability to find keywords” is different. It doesn’t require any particular level of knowledge — just fingers that can type a search query into Google. And if you discover a new keyword that feels too difficult to understand right now, you don’t have to learn it immediately.

The smallest value of acquiring a keyword is knowing that “something like this exists in the world.” If you know the keyword exists, you can come back to it later when your knowledge has deepened. Then you study it, ask more questions, discover the next keyword, and repeat. (If you work as a developer, the day will come when you need to learn that keyword.)

Wrapping Up

I’ll admit the title “Question Driven Thinking” sounds grandiose, but as I mentioned, learning through questions isn’t something I invented — it’s a well-known learning method.

This approach of gradually finding answers through questions has been used since ancient Greece. The process of asking yourself questions to discover what you don’t know and then seeking answers is something Socrates himself practiced extensively.

The man who left us the wise words: knowing that you know nothing is the wisest thing of all

The man who left us the wise words: knowing that you know nothing is the wisest thing of all

The truth is, after roughly ten years of schooling where we memorized math formulas, vocabulary words, and exam question patterns, we’re much more accustomed to rote memorization. In school, asking questions usually just got you labeled as the weird kid who makes class run long. (Along with the bonus title of “attention-seeker.“)

But simply asking “why?” can transform flat knowledge like “A is B” into deeper knowledge like “A is B because of ~.” We need to get comfortable with questioning. Ask questions, discover what you don’t know, find answers, respond to your own questions, and keep generating new keywords along the way.

And when you ask yourself questions, thoughts keep building on each other and deepening — which makes this a great method not just for studying but for organizing your thinking too. I’d encourage you to give it a try.

That’s all for this post on Question Driven Thinking.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Can I Really Say I Know Frontend?

EssayHow Developers Survive Through Learning

EssayHow to Find Your Own Color – Setting a Direction for Growth

EssayWhy I Share My Toy Project Experience

Essay/Soft SkillsMigrating from Hexo to Gatsby

Programming/Tutorials