Simplifying Complex Problems with Math

Think math is hard? Finding patterns makes problem-solving easier

Recently, many IT companies conduct coding tests when hiring developers. While each company differs in the style of problems they pose, most seem to prefer simple algorithm problems or problems that mix in real-world scenarios, like those on Codility or Programmers.

Given the nature of these problems, you need to use CS fundamentals, problem analysis skills, and intuition in various combinations — so short-term practice won’t dramatically improve your abilities.

These problems don’t simply ask us “Do you know this algorithm?” but rather “What approach would you like to use to solve this?”

While data structures and algorithms themselves can be mastered to some degree by studying and implementing them a few times, the ability to analyze problems, simplify them, and choose appropriate methods isn’t something you can develop through study alone.

I’ve been solving these kinds of problems recently while job hunting, and I’ve definitely felt that while my CS fundamentals are lacking, my ability to analyze problems and choose good approaches is even more lacking.

So while re-studying data structures and algorithms from scratch, I also started thinking about what methods might help develop problem-solving abilities.

Simplifying Problems with Mathematical Thinking

After getting thoroughly destroyed in interviews recently, I started re-studying CS fundamentals and JavaScript basics from the beginning. But when I tried to use this knowledge to solve coding test problems, things didn’t go as well as I’d hoped.

As most people know, many coding test platforms show you how others solved the same problem after you complete it. Honestly, this curiosity is part of why I solve problems.

During this process, I once saw someone solve a problem that most people had solved with brute force using just a few simple arithmetic operations.

The world is vast and geniuses are plentiful

The world is vast and geniuses are plentiful

Of course, I had also solved that problem with brute force and thought that was the only way. But this genius had found patterns in the problem and simplified it.

Sure, the code was a bit obscure and might be controversial for production use, but I was shocked that a complex problem most people solved with brute force could be solved with just a few simple equations.

What I took away from this was the need for mathematical thinking. Of course, algorithms are also generalizations of efficient solutions based on such mathematical thinking, but what I wanted was more fundamental problem-solving ability.

When I say mathematical thinking, I don’t mean reading a problem and immediately writing complex equations. Analyzing problems written in natural language, breaking them down into solvable pieces, and finding patterns all stem from mathematical thinking. After all, mathematics itself is the discipline of simplifying complex problems and finding patterns to generalize them.

As I mentioned in my Do Developers Need to Be Good at Math? post, the math I’m talking about isn’t difficult theories or formulas.

This is my personal opinion, but I think understanding “the properties of numbers” is most important. For example, knowing that adding 1 to an odd number gives an even number, or that the sum from 1 to 100 can be calculated as 101 * 100 / 2.

For this reason, I recently read a book called “Think Like a Programmer with Math,” and since some interesting problem-solving methods appeared early in the book, I’d like to share those problems and their solutions.

What Day of the Week Is It 10 Billion Days from Now?

Finding the day of the week days later is a classic problem requiring mathematical thinking.

Even without going to coding tests, this is a problem you encounter quite often just handling business logic in daily development. So as a warm-up, let’s look at this relatively familiar day-of-the-week problem first.

As I write this on October 29, 2019, it’s “Tuesday.” What day of the week will it be 10 billion days from now?

Well, thinking simply, since today is Tuesday, we could approach this sequentially: 1 day later is Wednesday, 2 days later is Thursday, and so on.

console.time('calc');

const week = ['Sun', 'Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat'];

let today = 2;

let shift = 0;

for (let i = 0; i <= Math.pow(10, 10); i++) {

shift = i % week.length;

}

today += shift;

if (today > week.length - 1) {

today -= week.length;

}

console.log(week[today]);

console.timeEnd('calc');Sat

calc: 60948.138msEven though computers these days have great processing power and work without pay like SCVs, making one calculate a loop that repeats 10 billion times is just cruel. Since this algorithm has time complexity, it takes over a minute just running the loop.

We can’t solve it this brutishly, so we need to find another way. Fortunately, we know that days of the week repeat every 7 days. If today is Tuesday, 7 days from now is also Tuesday, and 14 days from now is also Tuesday.

In other words, there’s a “periodicity” where days repeat. Once we’ve found the pattern that any day that’s a multiple of 7 from today is Tuesday, the rest becomes simple.

Since continuously dividing any number by 7 while incrementing by 1 produces a periodic pattern of 0-6, just like finding multiples, we can divide 10 billion by 7 and check the remainder.

console.time('calc');

const week = ['Sun', 'Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat'];

let today = 2;

const shift = Math.pow(10, 10) % week.length;

today += shift;

if (today > week.length - 1) {

today -= week.length;

}

console.log(week[today]);

console.timeEnd('calc');Sat

calc: 0.156msExecution time dropped from 60000ms to 0.156ms. By finding periodicity in the problem and connecting it to the periodicity of remainders, we can solve the problem easily using remainders without brute force.

Let’s Also Find the Day Days from Now

Let’s take this one step further. Can we find the day of the week days from now using this method? I don’t know what 10 to the power of 100 million is called, but considering that the number of all atoms in the observable universe is about , is definitely an astronomically huge number.

Obviously, far exceeds JavaScript’s Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER, so calculation using the above method is impossible. From here on, simplifying the problem and finding periodicity becomes more important than leaving the calculation to the computer.

Since today is Tuesday, October 29th, let’s look at the days of the week days from now. Using the logic from the example we just made to look up to days later, I found the following pattern. Since listing all results would make the table too long, I’ll only include results from days onward.

| Days | Day | Index |

|---|---|---|

| days later | Wed | 3 |

| days later | Fri | 5 |

| days later | Thu | 4 |

| days later | Mon | 1 |

| days later | Sat | 6 |

| days later | Sun | 0 |

| days later | Wed | 3 |

| days later | Fri | 5 |

| days later | Thu | 4 |

| days later | Mon | 1 |

| days later | Sat | 6 |

| days later | Sun | 0 |

| days later | Wed | 3 |

From this process, I discovered two pieces of information: the days repeat in the order Wed, Fri, Thu, Mon, Sat, Sun, and today’s day Tuesday never appears.

In other words, the same day returns every time the exponent of 10 increases by 6. Put another way, the same day returns every time 6 more zeros are added.

This means we can find the day using the same method as before, using the remainder when dividing the exponent of 10 by 6.

const week = ['Wed', 'Fri', 'Thu', 'Mon', 'Sat', 'Sun'];

const exp = Math.pow(10, 8);

console.log(week[exp % week.length]);SatAlthough the computer can’t hold the enormous number so we can’t calculate it directly, by understanding the periodicity of days due to exponent increase, we can find the day of the week in an unimaginably distant future. (Though what’s the point of calculating this anyway…)

If we had tried to solve this problem with the honest method we used above, it would have been impossible. But by analyzing the problem and finding periodicity, we managed to solve it somehow.

Tiling a Bathroom Floor

Unlike the day-finding problem we just solved, where the repeating numbers with a clear regular period are quite visible, most problems we encounter in daily life don’t show their patterns so obviously.

What’s needed then is analyzing the problem and finding patterns. The real significance of being able to use the number property of periodicity lies in being able to create and find patterns. This time, it’s a problem about validating using those patterns.

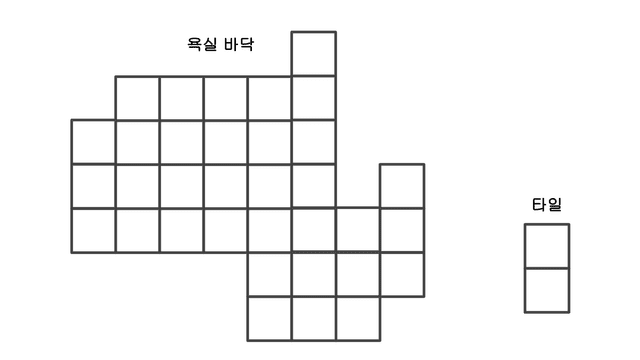

Evan got a job at a tile installation company and is doing his first bathroom floor installation. But since today is his first day, Evan accidentally only brought rectangular tiles that are 1cm wide and 2cm long.

Fortunately, all bathroom floors are standardized as grids of 1cm × 1cm squares, but the shape and number of squares vary for each bathroom.

Evan needs to completely fill the bathroom floor with his rectangular tiles, but depending on the bathroom floor shape, some jobs may be impossible. Plus, Evan is weak and can’t break tiles in half to use them.

How can Evan determine whether a job is possible?

const floor = [

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0],

];For this problem, we could check each possible way to fill the bathroom floor with tiles one by one, but there are too many possibilities and the logic would obviously become complex.

What if we count the number of squares on the bathroom floor? Since a tile covers two squares, if the number of floor squares is odd, Evan’s tiles could never fill the floor.

But sadly, the total number of squares in this problem is an even 34, and knowing whether the floor squares are odd or even alone can’t solve this problem anyway. Is there a more reliable verification method?

This problem might seem to have nothing to do with periodicity, but there’s actually a very simple hidden pattern: Evan’s tile consists of two squares.

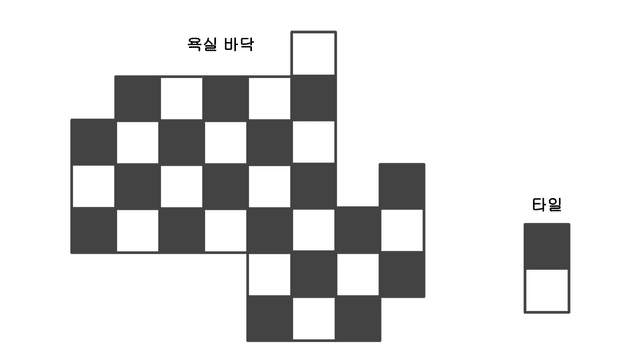

To make thinking easier, let’s color the tiles and floor.

After coloring like this, Evan’s tile becomes a two-square tile consisting of 1 black square and 1 white square. This means if Evan’s tiles can completely fill the bathroom floor without gaps, the number of black squares and white squares on the bathroom floor must be equal.

However, our given bathroom floor has 16 black squares and 18 white squares. This means this bathroom floor cannot be filled with Evan’s tiles.

This problem is solved by assigning “the periodicity of black and white” to Evan’s two-square tile. If the color period of Evan’s tile doesn’t match the bathroom floor’s period, that bathroom floor cannot be filled.

So if we define black squares as -1 and white squares as 1, and alternately add -1 and 1 each time we encounter a floor square, if the final value is 0, the number of black and white squares is equal.

const floor = [

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0],

];

const tile = [-1, 1];

let count = 0;

let tileIndex = 0;

floor.forEach((row, index) => {

tileIndex = Number(index % 2 === 0);

row.forEach(col => {

if (col === 1) {

count += tile[tileIndex];

}

tileIndex = tileIndex === 0 ? 1 : 0;

});

});

console.log(`The difference between black and white tiles is ${Math.abs(count)}.`);The difference between black and white tiles is 2.The reason we reset tileIndex when iterating each row is that this matrix has an even number of columns. Since the tile’s period is also even, the color of the last tile in the previous row appears again at the start of the next row. (If we made the columns odd, this step wouldn’t be needed — I made the problem wrong…)

Although the problem seemed to have nothing to do with periodicity at first glance, by finding repeating patterns within the problem and assigning periodicity, we can solve the problem in a simpler way.

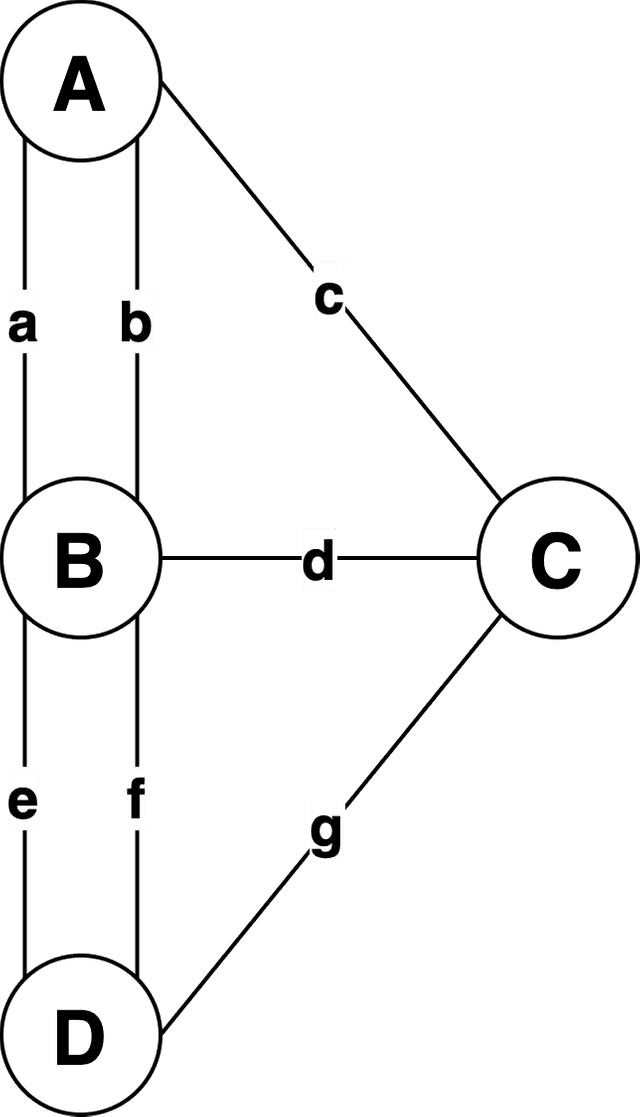

Drawing Without Lifting Your Pen: Proving the Königsberg Bridge Problem

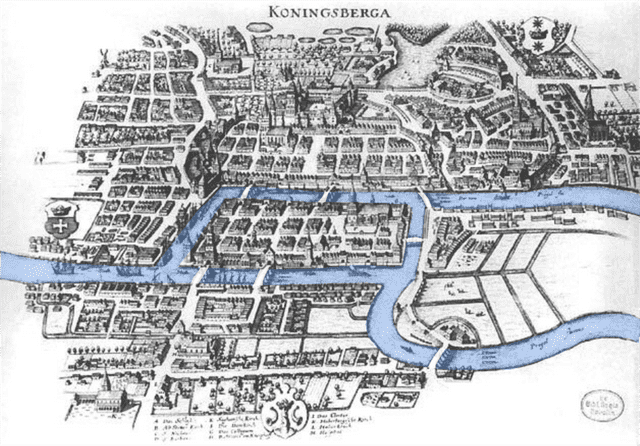

The Königsberg bridge problem is a very famous problem that initiated modern topology. It uses bridges in the city of Königsberg in Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia).

The Pregel River flows through the middle of Königsberg, and there are 7 bridges connecting the islands in the center.

Starting from any point, can you cross all bridges exactly once?

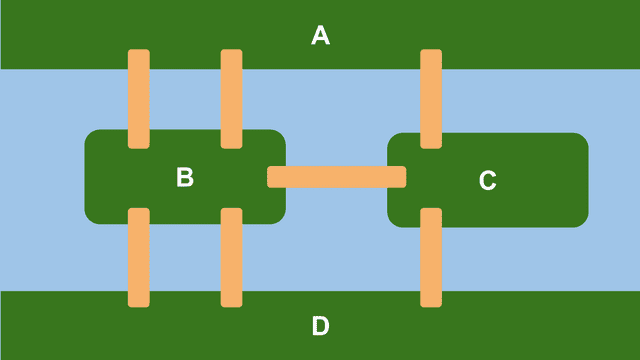

In other words, it’s a problem of drawing without lifting your pen. Since it’s hard to think about the problem as-is, let’s simplify the diagram, assign identifiers to each region, and organize the problem conditions.

- You can start from any point.

- You must cross all bridges.

- You cannot cross a bridge you’ve already crossed.

- You can visit each region any number of times.

- You may or may not return to the starting region.

After a few attempts drawing with a pen, you get the feeling it’s probably impossible. But to conclude that “it’s absolutely impossible to cross,” we need to prove why it’s impossible. Maybe there’s a way we just haven’t found yet.

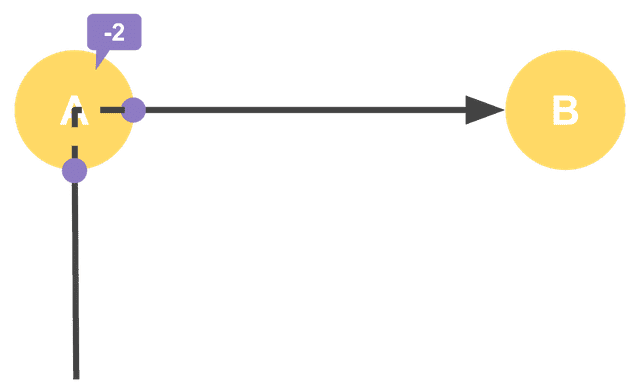

First, to think about this problem more easily, let’s redraw it not as a complex map but as a simplified graph.

In this graph, the points representing regions A, B, C, D are called vertices, the lines representing bridges a - g are called edges, and the number of edges attached to each vertex is called the degree.

In the Königsberg problem, crossing a bridge means moving from one vertex to another, and not being able to cross a bridge again means we must delete the edge used to move to another vertex.

Looking at the cases where we can move by crossing bridges, we can roughly classify them into three cases: starting, arriving at the end, and passing through. There’s a hidden pattern in the number of edges deleted in these three cases.

When Starting

When departing from any vertex to move to another, only the edge serving as the exit will be deleted. That is, the starting vertex’s degree decreases by 1.

When Arriving at the End

Opposite to starting, the arriving vertex only needs to delete the edge that served as the entrance, so that vertex’s degree decreases by 1.

When Passing Through

When passing through, we must delete both the edge serving as entrance and the edge serving as exit, so that vertex’s degree decreases by 2.

In other words, successfully drawing without lifting your pen on a graph means that when there are no more edges to cross while traversing vertices, “all vertices must have degree 0.” If there exists a vertex with non-zero degree, it means that vertex still has uncrossed edges connected to it, so the drawing without lifting your pen has failed.

Here, we can get a hint to solve this problem from the fact that each vertex’s degree decreases by either 1 or 2.

Focus on Whether the Degree Is Odd or Even

When the degree decreases by 1, the odd/even status changes each time it’s performed. When it decreases by 2, the odd/even status never changes.

The reason we’re talking about whether vertex degrees are odd or even is because “0 is even.”

That is, if we understand the odd/even pattern of how degrees change when departing, arriving, or passing through vertices, we can easily determine whether this graph allows drawing without lifting your pen without examining all possible cases.

When Start and End Are the Same

As we observed above, intermediate vertices that are passed through always have their degrees decrease by 2, so the odd/even status never changes no matter how many times they’re passed through.

This means for a passing vertex’s degree to become 0 regardless of how you traverse, that vertex’s degree must be even from the start.

If a passing vertex’s degree is odd, it will inevitably end up with degree 1, and if you arrive at that vertex via this edge, there are no remaining edges, so you can’t cross to another vertex.

Once you enter a passing vertex with odd degree, you can't get out

Once you enter a passing vertex with odd degree, you can't get out

Also, when start and end are the same, you decrease the starting vertex’s degree by 1 when first departing and decrease it by 1 again when arriving, so ultimately that vertex’s degree decreases by a total of 2.

In this case too, since the starting vertex’s odd/even status cannot change, it must have an even degree from the start. That is, when start and end are the same, for drawing without lifting your pen to succeed, “all vertices must have even degrees.”

When Start and End Are Different

When start and end are different, passing vertices still must have even degrees from the start, but this time since start and end are different, the starting and ending vertices must have odd degrees.

Intermediate passing vertices always have degrees decrease by 2, so odd/even doesn’t change, but at start and end, degrees decrease by only 1, so odd/even status changes.

That is, when start and end are different, the conclusion is “start and end must have odd degrees, all other vertices must have even degrees.”

Why Is Drawing Without Lifting Your Pen Impossible for the Königsberg Bridges?

Summarizing these two conditions, drawing without lifting your pen while traversing graph vertices is possible when “all vertices have even degrees OR there are exactly 2 vertices with odd degrees.” Let’s look at the graph representing the Königsberg bridges again and check if it meets these conditions.

The degrees of vertices in this graph are A=3, B=5, C=3, D=3 — all vertices have odd degrees, which doesn’t match any condition we found above.

Thus, it’s proven that the Königsberg bridges have a structure where drawing without lifting your pen is impossible.

In graph theory, such a drawing without lifting your pen — that is, a path that passes through all edges of a graph exactly once — is called an Eulerian trail. The reason is that the great Leonhard Euler had already proved this problem in 1735 and used it in his paper.

You can check the paper at Solutio Problematis ad Geometriam Situs Pertinentis, but as the title suggests, it’s not in English. Like most papers written by highly educated people of that era, it’s written in Latin, so actually reading it is difficult. But just in case there are any geniuses out there who, beyond my imagination, can read Latin, I’ll include it anyway.

Anyway, the key idea to note in Euler’s solution is that when investigating each vertex’s degree, he focused not on the degree itself but on the property of odd and even. Without understanding the pattern of how a vertex’s degree status changes between odd and even when departing, arriving, or passing through, this problem would have been difficult to solve.

Wrapping Up

The three problems we looked at in this post don’t use difficult mathematical formulas.

The inference that days from now must have some pattern based on the 7-day repeating pattern, being able to think of the black and white repeating pattern when looking at a two-square tile, being able to think of the pattern of odd/even changes in each vertex’s degree without examining all cases of graph traversal — these are all problem-solving approaches anyone can take if they just understand the properties of numbers, even without knowing complex mathematical formulas.

By understanding and using fundamental properties of numbers like this, you can solve complex problems simply. The sad part is that this isn’t an ability you can gain just through studying. To develop this ability, you just need to practice thinking this way a lot.

Solving many coding tests is of course good, but finding and analyzing patterns in various problems encountered in daily life might also help, right? For example, when a friend suggests meeting on November 10th, instead of checking your phone for what day it is, you could try calculating it yourself.

That wraps up this post on simplifying complex problems with math!

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Efficiently Calculating Averages of Real-Time Data

Programming/AlgorithmIs the Randomness Your Computer Creates Actually Random?

Programming/AlgorithmHeaps: Finding Min and Max Values Fast

Programming/AlgorithmDo Developers Need to Be Good at Math?

Programming/Essay/AlgorithmsEverything About Sorting Algorithms (Bubble, Selection, Insertion, Merge, Quick)

Programming/Algorithm