Heaps: Finding Min and Max Values Fast

The magic of O(log n) — fast min/max lookups using heaps

In this post, I want to explain and implement the heap — one of the most representative data structures.

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, I’m currently unemployed. Now that my month of healing in Prague is over, it’s time to start going to interviews. As everyone knows, there’s a very high chance of getting questions about basic algorithms or data structures in interviews. But since I’ve been neglecting my fundamentals study for about a year, I need to study again.

So I’m planning to review data structures first, starting with the heap — the one I remember least well.

What Is a Heap?

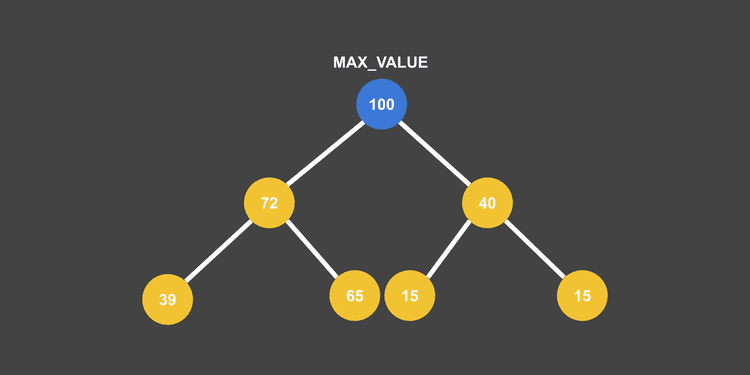

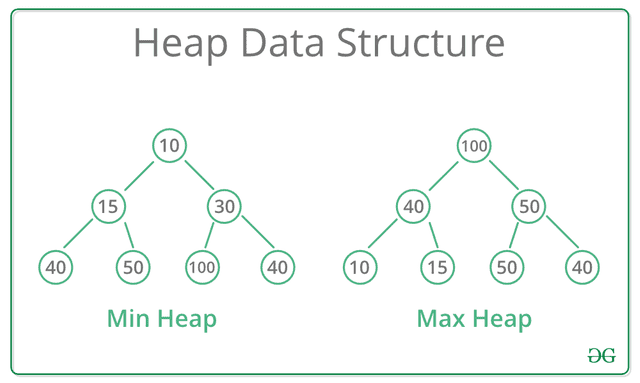

A heap is fundamentally a data structure based on a complete binary tree, where a size relationship exists between parent and child nodes. Because of this, the root node of a heap is either the largest or smallest value among all data in the heap.

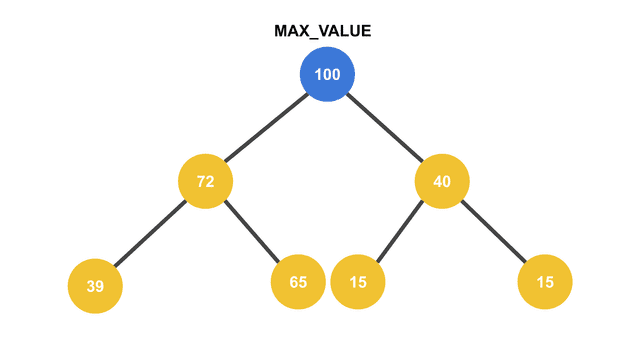

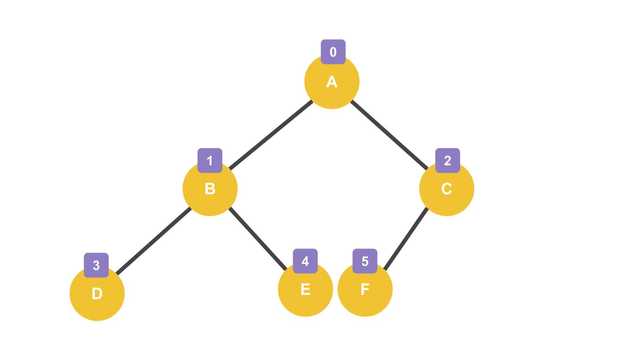

A Max Heap where the maximum value is at the root

A Max Heap where the maximum value is at the rootIt looks exactly like a complete binary tree

This means when you want to access the largest or smallest value in the heap, you can access it in one shot without any comparison operations, and the time complexity of this access operation is naturally . Because of this characteristic, heaps are useful in areas where you need to quickly find the largest or smallest value among multiple pieces of data.

Actually, if you simply want to access the maximum or minimum value in some data with time complexity, you could just sort a linked list or array and use that. Once you sort it once, you can just pluck values from the head whenever you need them.

However, when adding new data to this sorted data collection, you have to search through the entire collection to find the new maximum and minimum values and re-sort.

While linear data structures like arrays and linked lists require time complexity for this process, a binary tree sorted so that parents are larger or smaller than children only needs to compare with the newly added node’s parent nodes to maintain the sorted state, requiring only time complexity.

In other words, the more data you want to sort, the more advantageous it becomes.

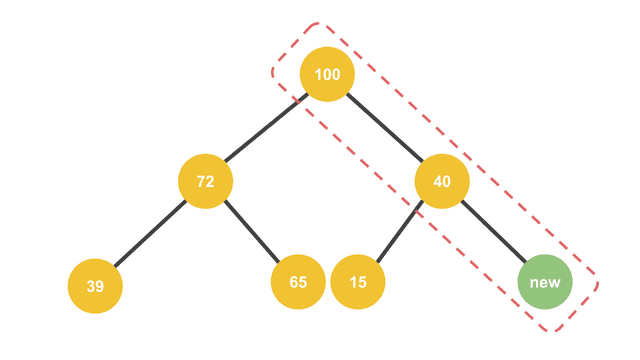

You only need to compare this part to re-sort, not the entire data

You only need to compare this part to re-sort, not the entire data

Since heaps are based on complete binary trees, the implementation method is also similar to complete binary trees. So before implementing a heap, I want to talk about the characteristics of complete binary trees first.

Complete Binary Tree

First, let’s look at the characteristics of complete binary trees, which form the basis of heaps. A binary tree is a tree where any single node can have at most 2 child nodes.

This means the maximum number of nodes that can be at each level is fixed, and you can assign unique indices to nodes.

A parent node must have 2 or fewer child nodes.

A parent node must have 2 or fewer child nodes.

A complete binary tree is a binary tree where nodes are created by filling from the left side of the tree sequentially. In a complete binary tree, you cannot create nodes at the next level until the current level is completely filled. In other words, all levels except the last must be completely filled with nodes.

Trees are usually implemented using linear data structures like linked lists or arrays, and depending on the characteristics of linked lists and arrays, there are different pros and cons to consider. (The differences between linked lists and arrays aren’t the topic of this post, so I won’t explain them separately.)

Generally, trees are implemented using linked lists, but for complete binary trees, implementing with arrays is more efficient.

Why Arrays Are More Efficient

Actually, the reason linked lists are generally used to implement trees is that implementing trees with arrays is too inconvenient due to the fixed memory allocation nature of arrays.

However, with complete binary trees, these inconveniences disappear, so you can fully take advantage of arrays’ benefits.

Easy access to any node

This takes full advantage of arrays’ biggest benefit: if you know the index, you can access that element directly. Since binary trees have a fixed maximum number of nodes at each level, you can find a specific node’s index with a simple formula and access it with time complexity.

First, if you want to access parent or child nodes based on a specific node, you can calculate indices as follows:

When the root node has index 0 and the current node has index :

- Parent node:

- Left child node:

- Right child node:

There’s also the method above for finding parent and children indices based on a specific node’s index, but the real advantage of array-based complete binary trees is that you can directly access a node at any level and position through a simple formula.

This is possible because you can easily calculate , the maximum number of nodes up to a specific level, using the properties of complete binary trees.

function getAllNodeCountByLevel (level = 1) {

return 2 ** level - 1;

}

console.log(getAllNodeCountByLevel(3));7 // Maximum number of nodes in a complete binary tree with 3 levelsUsing this formula, you can easily find the index of the th node at the th level.

For example, if you want to find index of the th node at level of a complete binary tree, you get the total number of nodes up to level (one level above where you want to access), then add which th node you want to access within that level.

function getNodeIndex (level = 1, count = 1) {

return getAllNodeCountByLevel(level - 1) + count - 1;

}

console.log(getNodeIndex(3, 3));5 // Index of the 3rd node at level 3We subtract 1 at the end because we want the index, not the ordinal position. Don’t forget that array indices start from 0.

As such, complete binary trees implemented with arrays make it easy to access desired nodes through simple calculations, but with linked list implementations, you can’t access nodes directly and must traverse the tree.

No need to shift array elements back

Since arrays allocate contiguous memory space, inserting an element in the middle requires shifting elements back one position to secure new memory space — a sad situation. But linked lists can easily insert new elements in the middle just by changing prev and next values.

However, binary trees have the constraint that each node can have at most 2 children, so a tree of height has a fixed maximum of nodes. Once you allocate this much space in memory, you never need to shift array elements to insert new nodes in the middle.

The tree doesn’t become skewed

Generally, when an array-implemented tree becomes skewed, serious memory waste occurs. This is easier to understand with a diagram.

The diagram above shows an ideally balanced binary tree. If we implement this tree as an array, values would be stored in memory like this:

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | A | B | C | D | E | F |

It’s packed into memory with no empty spaces in between. Since node indices are assigned sequentially from the left of the tree, if you create child nodes from the left, you can avoid creating empty spaces in memory.

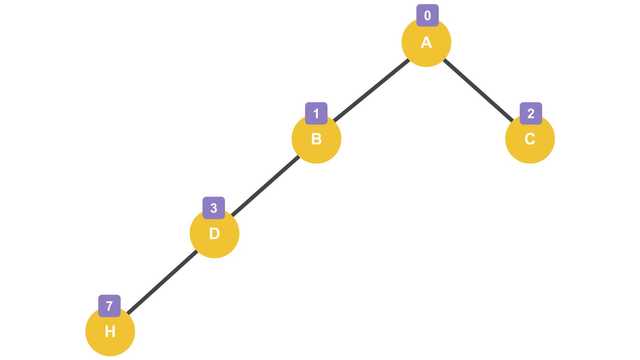

Of course, if you create the right child first while skipping the left, empty spaces will appear. But the bigger problem is when the tree becomes a skewed tree, heavily leaning to one side.

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | A | B | C | D | - | - | - | H |

As shown above, a heavily skewed tree creates empty spaces in memory because nodes are created at the next level while skipping intermediate indices. That’s why we say memory space is wasted. Of course, if it’s skewed to the right, the skipped indices are even larger, so the memory waste is even worse.

However, complete binary trees have constraints: nodes must be filled from the left sequentially, and you can’t fill nodes at the next level until all nodes in the current level are filled. So there’s no possibility of the tree becoming skewed, meaning no empty spaces in memory.

For these reasons, complete binary trees are often implemented taking advantage of arrays’ direct element access, and heaps, which are based on complete binary trees, are also mainly implemented with arrays for the same reasons.

Difference Between Complete Binary Trees and Heaps

Since heaps are based on complete binary trees, the basic node insertion and deletion algorithms are the same as regular complete binary trees. Node insertion is only possible at the end of the array, and after deleting a node, remaining nodes must be pulled forward to fill the empty space.

However, heaps have the condition that a size relationship must exist between parent and child nodes, so “functionality to re-sort nodes after insertion and deletion” is additionally required.

Also, since heaps are data structures designed to easily find maximum or minimum values within the tree, there’s rarely a need to directly access nodes in the middle of the tree. You just pluck and use the root node at Array[0]. Extracting the root node means deleting it, so the heap must be re-sorted accordingly.

Heaps are divided into max heaps and min heaps. In a max heap, the parent’s value must always be larger than the children’s. In a min heap, conversely, the parent’s value must be smaller than the children’s. That is, “the root of a max heap is the largest value in the heap” and “the root of a min heap is the smallest value in the heap.”

So implementing a heap means implementing a complete binary tree and adding sorting functionality appropriate for max heaps and min heaps.

Let’s Implement a Heap

Since the only difference between max heaps and min heaps is the sorting condition, I’ll only implement a max heap. As I mentioned above, for complete binary trees it’s more efficient to use arrays than linked lists, so I’ll implement using an array.

First, let’s create a small and cute MaxHeap class.

class MaxHeap {

constructor () {

this.nodes = [];

}

}If I wanted to implement with a linked list, I’d declare a separate Node class, but since I’m using an array, it’s extremely simple. Now let’s create a method for inserting values into the heap.

Inserting New Values: Bubble Up!

When inserting a new value into a heap, we always fill from the left of the tree according to complete binary tree rules. In other words, we just shove values one by one into the tail of the array using the push method. If this doesn’t make sense, go back and re-read the complete binary tree explanation above.

insert (value) {

this.nodes.push(value);

}Max heaps have the constraint that parents must always have larger values than children, so if the node we inserted has a larger value than its parent node, we need to swap their positions.

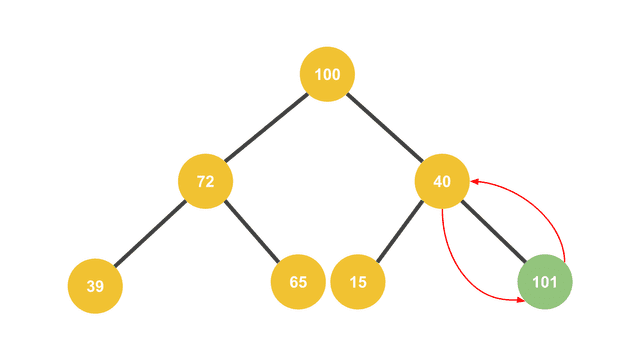

And we repeat this process until the inserted node reaches the root or has a smaller value than its parent — whichever condition is satisfied first.

The way the newly added value swaps with parent nodes and gradually rises up the tree resembles bubbles rising, which is why it’s called “Bubble Up.”

It swaps with the parent and gradually climbs up the tree

It swaps with the parent and gradually climbs up the tree

insert (value) {

this.nodes.push(value);

this.bubbleUp();

}

bubbleUp (index = this.nodes.length - 1) {

if (index < 1) {

return;

}

const currentNode = this.nodes[index];

const parentIndex = Math.floor((index - 1) / 2);

const parentNode = this.nodes[parentIndex];

if (parentNode >= currentNode) {

return;

}

this.nodes[index] = parentNode;

this.nodes[parentIndex] = currentNode;

index = parentIndex;

this.bubbleUp(index);

}The bubbleUp method compares the value of the node at the given index with its parent node’s value, and if the node has a larger value than the parent, it swaps their positions. Due to tree characteristics, this operation can be solved with divide and conquer, so I implemented it with recursive calls.

If we test at this point, we can see that the largest value in the heap is positioned at the head of the array — the root of the tree.

const heap = new MaxHeap();

heap.insert(1);

heap.insert(3);

heap.insert(23);

heap.insert(2);

heap.insert(10);

heap.insert(32);

heap.insert(9);

console.log(heap.nodes);[ 32, 10, 23, 1, 2, 3, 9 ]

When a value larger than the parent is added, it swaps positions with the parent

Extracting Values from the Root: Trickle Down!

Now that we’ve implemented value insertion and bubble up, let’s create a method to extract values from the root. This is the delete operation. When we extract the root node, its position becomes empty, so we need to re-sort the heap and fill the root node again.

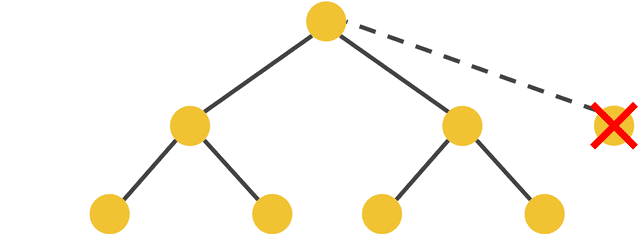

Instead of promoting the existing root node’s children to the root, we take the node at the very end of the tree and insert it as the root node. This is to reduce the number of operations by preventing empty spaces in the modified heap.

If we directly pulled up the children right below the root to use as the new root, the space where that node was would naturally become empty, and then we’d need comparison operations to determine which node to pull up from the next level.

And since heaps must always maintain the form of a complete binary tree, if the tree becomes skewed during this process, we’d have the hassle of rebalancing the tree.

So we use the last node as the new root node and swap positions while comparing with children. The way the new root node gradually moves down the tree resembles a water drop falling, which is why it’s called “Trickle Down.” (For a computer term, it’s somehow poetic…)

extract () {

const max = this.nodes[0];

this.nodes[0] = this.nodes.pop();

this.trickleDown();

return max;

}

trickleDown (index = 0) {

const leftChildIndex = 2 * index + 1;

const rightChildIndex = 2 * index + 2;

const length = this.nodes.length;

let largest = index;

if (leftChildIndex <= length && this.nodes[leftChildIndex] > this.nodes[largest]) {

largest = leftChildIndex;

}

if (rightChildIndex <= length && this.nodes[rightChildIndex] > this.nodes[largest]) {

largest = rightChildIndex;

}

if (largest !== index) {

[this.nodes[largest], this.nodes[index]] = [this.nodes[index], this.nodes[largest]];

this.trickleDown(largest);

}

}Trickle down can also be solved through divide and conquer via recursive calls, just like bubble up.

The trickleDown method compares the parent node’s value with the left and right child nodes’ values, and if a child has a larger value than the parent, it swaps their positions.

Simply put, the one with the largest value among the three nodes takes the parent position. If the parent loses this power struggle, think of it as being demoted to where its child used to be.

The succession process somehow reminds me of this guy

The succession process somehow reminds me of this guy

If the parent and child positions are swapped during this process, the swapped parent node’s index is passed as an argument to trickleDown again to repeat this process.

Now let’s do a simple test like we did with bubble up. The values going into the heap are the same as we used for bubble up earlier.

const heap = new MaxHeap();

heap.insert(1);

heap.insert(3);

heap.insert(23);

heap.insert(2);

heap.insert(10);

heap.insert(32);

heap.insert(9);

const length = heap.nodes.length;

for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {

console.log('MAX_VALUE = ', heap.extract());

console.log('HEAP = ', heap.nodes);

}MAX_VALUE = 32

HEAP = [ 23, 10, 9, 1, 2, 3 ]

MAX_VALUE = 23

HEAP = [ 10, 3, 9, 1, 2 ]

MAX_VALUE = 10

HEAP = [ 9, 3, 2, 1 ]

...

Note that we take a node from the very end of the tree to use as the root node

Wrapping Up

A heap itself is simply a complete binary tree where data is loosely sorted, but because the root always contains the maximum or minimum value among all data in the heap, it can be used in various applications.

One representative use is a sorting method for linear data structures called heap sort. Currently, V8’s Array.prototype.sort method uses quick sort, but in the early days, it briefly used heap sort — a sorting algorithm that uses heaps.

Anyway, it feels good to revisit these basic data structures I had forgotten about.

Since heaps are used in so many places, it doesn’t hurt to know them, and I remember being asked about them quite often in interviews too. Now that I’ve become an unemployed developer with no connection to any company’s business logic, I should take this opportunity to study the fundamental theory I’ve been neglecting in more detail.

That wraps up this post on heaps — the data structure that helps you find minimum and maximum values fast.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Is the Randomness Your Computer Creates Actually Random?

Programming/AlgorithmDiving Deep into Hash Tables with JavaScript

Programming/AlgorithmSimplifying Complex Problems with Math

Programming/Algorithm[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes

Programming/JavaScriptBeyond Classes: A Complete Guide to JavaScript Prototypes

Programming/JavaScript