Why Did HTTP/3 Choose UDP?

The web standard is changing. HTTP/3 picks UDP for speed.

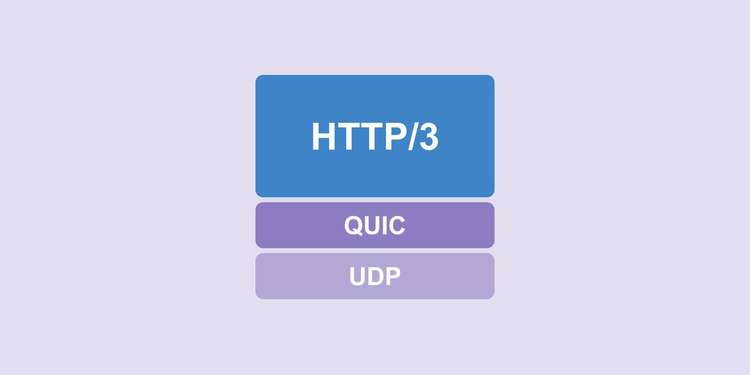

HTTP/3 is the third major version of HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol). Unlike HTTP/1 and HTTP/2, it communicates using QUIC, a UDP-based protocol. The biggest difference between HTTP/3 and its predecessors is that it runs on UDP instead of TCP.

I first learned about HTTP/3 after reading a post someone shared: HTTP/3: the past, the present, and the future. My honest first reaction when I saw the title was:

Wait, HTTP/2 was only released about 4 years ago. HTTP/3 already? Isn’t it just in the design phase?

But after reading the post, I was surprised to learn that Google Chrome had already shipped a Canary build with HTTP/3 support — it was at the point where you could actually try it. It took roughly 15 years to go from HTTP/1 to HTTP/2, yet just 4 years later, the next major version was already usable.

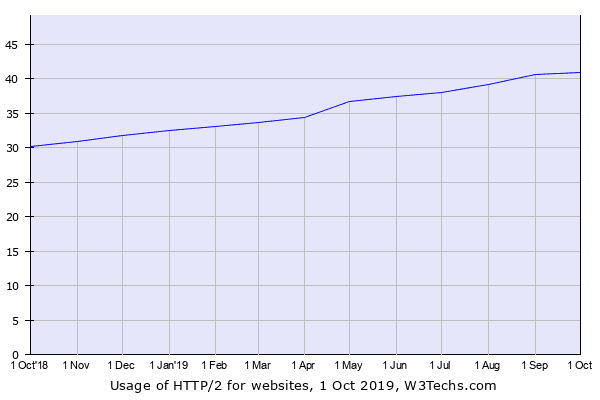

On top of that, the global adoption rate of HTTP/2 was still only around 40% at the time. That’s how recent HTTP/2 still was.

HTTP/2 adoption rate as of August 2019, surveyed by W3Techs.com

HTTP/2 adoption rate as of August 2019, surveyed by W3Techs.com

With programming languages and frameworks, the publisher pushes an update and users upgrade — done. But protocols are agreements, requiring coordination between software vendors, so I assumed such rapid changes wouldn’t happen often.

Technology moves fast, sure, but HTTP is a foundational web protocol. The fact that such a dramatic change happened in just 4 years was genuinely surprising. (Web developers who had just adopted HTTP/2 a few months earlier were in tears.)

The other thing that surprised me was that HTTP/3 uses UDP instead of TCP. There’s no rule saying web protocols must use TCP, but from what we learn in school to what we use in practice, HTTP being defined on top of TCP was so deeply ingrained that using UDP felt novel. I couldn’t help but wonder: “Why abandon TCP when it works perfectly fine?”

Technically, HTTP/3 hadn’t been formally released yet — it was still in the testing phase. But as mentioned above, Chrome already had a Canary build with HTTP/3 support, Mozilla Firefox was planning to support it in Nightly builds soon, and cURL was offering HTTP/3 as an experimental feature. It seemed very likely that HTTP/3 would become the main protocol in the near future.

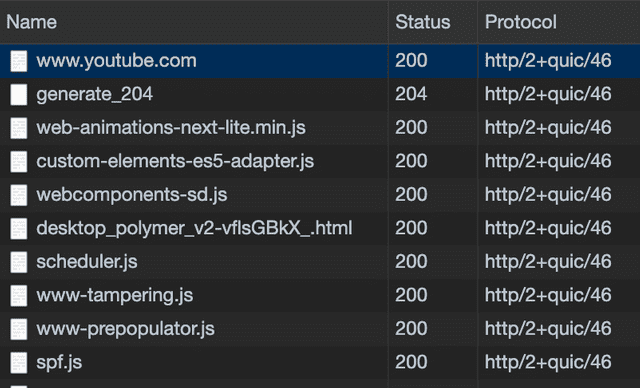

If you want to try HTTP/3 in Google Chrome, you can launch it from the terminal with the --enable-quic and --quic-version=h3-23 flags:

$ open -a Google\ Chrome --args --enable-quic --quic-version=h3-23 The entries showing http/2+quic/46 are connections using the HTTP/3 protocol

The entries showing http/2+quic/46 are connections using the HTTP/3 protocol

As a web developer, I couldn’t just ignore the fact that HTTP was getting a major update. I was also curious about what using UDP actually meant. So I dug into HTTP/3, and this post is a summary of what I found.

A Brief Introduction to HTTP/3

HTTP/3 was originally called “HTTP-over-QUIC.” Mark Nottingham, chair of both the HTTP and QUIC working groups within the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force), proposed renaming the protocol to HTTP/3. The proposal was accepted in November 2018, and the name changed from HTTP-over-QUIC to HTTP/3.

In other words, HTTP/3 is HTTP running on top of a protocol called QUIC. QUIC stands for “Quick UDP Internet Connection” — literally, a protocol that establishes internet connections using UDP. (It’s pronounced just like “quick,” by the way.)

HTTP/3 uses QUIC, and QUIC uses UDP, so we can say HTTP/3 uses UDP.

So what exactly is QUIC, and why can it achieve faster transmission speeds than TCP? To understand that, we first need to know why TCP is considered slow and what advantages UDP offers.

Why Is TCP Considered Slow?

When I first learned about the differences between TCP and UDP in a networking class, my professor said it would definitely be on the exam, so I memorized this table:

| TCP | UDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Connection | Connection-oriented | Connectionless |

| Packet exchange | Virtual circuit | Datagram |

| Order guarantee | Guaranteed | Not guaranteed |

| Reliability | High | Low |

| Speed | Slow | Fast |

From this table, the takeaway is roughly “TCP is reliable but slow” and “UDP is unreliable but fast.” The “reliability” here refers to whether all data sent by the sender arrives intact at the receiver — by checking packet ordering, detecting packet loss, and so on.

TCP uses several mechanisms to ensure reliable communication between client and server. But these mechanisms are themselves communications between client and server, so they inevitably add latency. And since these processes have been part of the TCP standard since its inception, you can’t just skip them.

To reduce latency, you’d need to touch things outside of TCP’s defined features — but there are many constraints. No matter how much you increase bandwidth, the data we need to transmit keeps growing with advancing technology, so things will eventually get slow again. And even if you increase the raw transmission speed, you can’t go faster than the speed of light.

This is exactly why HTTP/3 chose QUIC, a UDP-based protocol — it opted to modify the protocol itself to overcome these constraints. But TCP is such an old protocol, deeply defined at the low level down to the kernel, that overhauling it would be a massive undertaking. So they chose UDP instead.

Let’s look at why the mechanisms TCP uses for reliable communication are considered slow.

3-Way Handshake

TCP is an extremely polite protocol. Before starting or ending communication, it always asks whether both sides are ready, establishes packet ordering, and only then begins the actual data transfer.

The process at the start of communication is called the 3-Way Handshake, and the process at the end is called the 4-Way Handshake. Since the purpose of this post isn’t to cover these in detail, I’ll only explain how the 3-Way Handshake works.

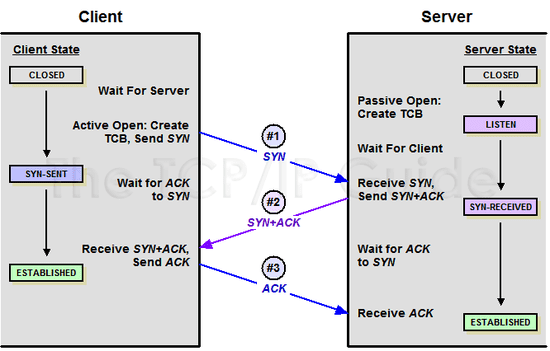

The 3-Way Handshake process when starting communication

The 3-Way Handshake process when starting communication

As shown above, when a client first creates a TCP connection to a server, they exchange SYN and ACK packets. The values inside these packets allow client and server to verify packet ordering and confirm that packets were properly received.

This process requires 3 round trips of communication. If you’re on macOS or Linux, you can observe this process directly using the tcpdump utility in your terminal.

Note that running tcpdump without options will monitor all packets on the device, making it hard to find what you want. So I captured only the communication with a blog server running on loopback:

$ sudo tcpdump host localhost -i lo0

IP localhost.53920 > localhost.terabase: Flags [S], seq 1260460927, win 65535

IP localhost.terabase > localhost.53920: Flags [S.], seq 3009967847, ack 1260460928, win 65535

IP localhost.53920 > localhost.terabase: Flags [.], ack 3009967848, win 6379sender > receiver: Flags [flag type], header values

The original output contains more information, but I’ve trimmed it to what’s needed for the explanation. The key fields here are Flag, seq, and ack. Let’s break them down.

localhost.53920 is the client, and localhost.terabase is the server. Each line’s first field shows sender > receiver, so the first packet is from client to server, the second from server to client. Each line also has a Flag that indicates what type of packet it is:

| Flag | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| S | SYN | Client sends a sequence number to the server to initiate connection |

| S. | SYN-ACK | Server generates an ACK value and responds to the client |

| . | ACK | Response using the ACK value |

After this communication, client and server can establish a reliable TCP connection. Since it takes 3 exchanges, it’s called a 3-Way Handshake.

What happens during this process that creates a reliable connection? Looking more closely, the client and server go through roughly this flow:

Line 1: Client sends a sequence number in the

seqfield to the server

Line 2: Server increments the client’s sequence number by 1 and sends it back in theackfield

Line 3: Client increments the server’s sequence number by 1 and sends it back in its ownackfield

The 3-Way Handshake begins when a client sends a random sequence number to the server to create a new TCP connection. This sequence number later serves as the ordering guide when the receiver reassembles packets from the sender.

Both client and server increment the received seq (sequence number) by 1 and place it in their own ack (acknowledgment number) field, essentially saying: “This packet follows the sequence number you sent earlier.”

These 3 exchanges are the 3-Way Handshake. Through this process, client and server inform each other that they’re ready to exchange data and establish the sequence numbers needed for subsequent data transfer. Ending a connection goes through a similar 4-Way Handshake process, requiring 4 exchanges.

In short, as long as you’re using TCP, you must go through this tedious process before any real communication can begin.

HTTP/1 processed only one request per TCP connection and then closed it, so this handshake had to happen with every single request. HTTP/2 changed this by maintaining a single TCP connection and handling multiple requests over it, minimizing handshakes.

Even in the transition from HTTP/1 to HTTP/2, the handshake process itself was left untouched — they only minimized how often it occurred to reduce latency. This is because handshaking is mandatory as long as TCP is in use.

HTTP/3, however, chose UDP, eliminating the handshake process entirely and securing connection reliability through other means.

HOLB (Head-of-Line Blocking)

There’s another problem with HTTP over TCP: Head-of-Line Blocking (HOLB). While HTTP-level HOLB and TCP-level HOLB technically mean different things, they share the same essence — a bottleneck in one request increases overall latency.

In TCP communication, packets must be processed in exact order. The receiver must reassemble packets using the sequence numbers exchanged with the sender.

If a packet is lost mid-transmission, the data can’t be fully reassembled, so it’s never ignored. The sender must confirm that the receiver got every packet, and if any packet wasn’t received, it must be retransmitted.

Since packets must be processed in order, subsequent packets can’t be processed until previous ones are parsed. When a packet is lost or the receiver’s parsing speed is slow, this bottleneck is called “HOLB.” This is a fundamental TCP issue affecting not just HTTP/1 but HTTP/2 as well.

To solve these problems, HTTP/3 chose to run on QUIC, a protocol built on UDP. Let’s now look at what QUIC actually is and what advantages UDP offers over TCP.

Why HTTP/3 Uses UDP

Since HTTP/3 runs on QUIC, understanding HTTP/3 means focusing on QUIC. QUIC is a UDP-based protocol developed by Google to solve TCP’s problems and break through latency limitations.

QUIC was designed from the start with a focus on optimizing TCP’s handshake process, and it achieved this by using UDP.

As the name “User Datagram Protocol” suggests, UDP uses a datagram approach with independent packets that have no inherent ordering. Since datagrams only need a destination — they don’t care about the intermediate path — there’s no end-to-end connection setup either. In other words, no handshake is needed.

The bottom line is that UDP is faster because it skips the many steps TCP takes to ensure reliability. But does using UDP mean we lose the reliability and data integrity that TCP provided?

No. Even with UDP, you can implement all the features TCP has. UDP’s real advantage is that it’s highly customizable.

UDP Is a Blank Canvas

In school, I was taught that the biggest difference between UDP and TCP is “UDP is faster but less reliable than TCP.” This is half right and half wrong.

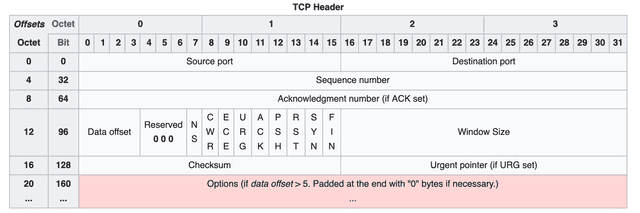

UDP has no features defined beyond data transmission itself, so it’s true that the protocol doesn’t guarantee reliability on its own. But put differently, it’s a blank-slate protocol with nothing but data transmission capability. To get a sense of how many features TCP packs in for reliability and congestion control, just look at its header:

TCP's header, already packed with information

TCP's header, already packed with information

TCP was designed a long time ago and includes so many features that its header is nearly full. If you want to implement custom features beyond TCP’s built-in ones, you’d use the Options field at the bottom, but since it can’t grow infinitely, it’s capped at 320 bits.

And the later-defined options like MSS (Maximum Segment Size), WSCALE (Window Scale Factor), and SACK (Selective ACK) already take up most of that options space, leaving barely any room for custom features.

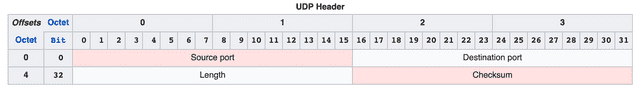

UDP, on the other hand, was designed with a sole focus on data transmission, so its header is practically empty:

Compared to TCP, UDP's header is noticeably bare

Compared to TCP, UDP's header is noticeably bare

UDP’s header contains only source port, destination port, packet length, and checksum. The checksum is used for verifying packet integrity, but unlike TCP’s mandatory checksum, UDP’s checksum is optional.

In other words, while the UDP protocol itself is less reliable than TCP and lacks flow control, depending on how a developer implements the application layer, it can achieve TCP-like functionality.

Sure, it’s convenient that TCP provides all those reliability features out of the box. But the unfortunate part is that these features are mandatory processes defined in the protocol itself — developers can’t customize them. This makes it nearly impossible to even attempt reducing the latency they introduce.

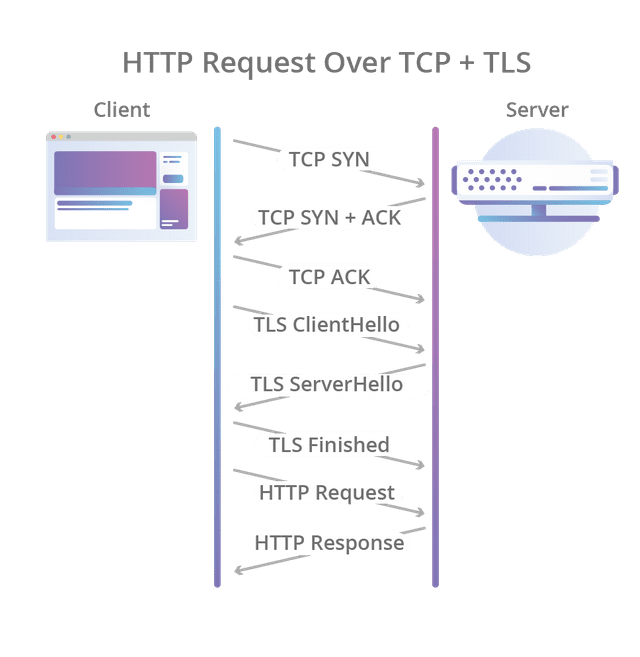

If you add TLS on top of TCP, you have to go through all of this before communication even begins

If you add TLS on top of TCP, you have to go through all of this before communication even begins

To reduce latency, you’d need to modify things outside the protocol. But as I mentioned, the areas a typical developer can touch in the communication process are limited. (We just have to wait for the telecom giants to lay down the infrastructure.)

If the difference between TCP and UDP still isn’t clicking, think of it as “a heavy, full-featured library” versus “a lightweight library with only the essentials.”

For example, lodash in the JavaScript world is incredibly feature-rich and convenient, but most people don’t use every single method. It’s handy, but you’re bundling features you’ll never use.

A small library with a single purpose has fewer features than lodash, but you can pick exactly what you need. The tradeoff is that anything the library doesn’t support, you have to implement yourself. In this analogy, lodash is TCP and the small single-purpose library is UDP.

This is why Google chose UDP when building QUIC: TCP was too difficult to modify, and the blank-slate nature of UDP made it easy to extend QUIC’s capabilities.

How HTTP/3 Improves Over Previous Protocols by Using UDP

So far we’ve briefly covered why QUIC, the backbone of HTTP/3, chose UDP over TCP. What concrete benefits does using UDP actually bring? Is HTTP/3 truly better than the old HTTP + TCP + TLS approach?

The answer can be found in the Chromium Projects’ QUIC Overview document. Let’s look at the advantages Google describes.

Reduced Latency in Connection Setup

Since QUIC doesn’t use TCP, it doesn’t need the tedious 3-Way Handshake to start communication. A cycle where the client sends a request and the server processes and responds is called an “RTT (Round Trip Time).” TCP requires at least 1 RTT to create a connection, and if you add TLS encryption, the TLS handshake adds up to a total of 3 RTTs.

QUIC, on the other hand, requires only 1 RTT for the initial connection setup. The client sends a signal to the server, the server responds, and real communication begins immediately. The connection setup time is roughly halved.

How is this possible? The reason is simpler than you’d expect. During the first handshake, QUIC sends the data along with the connection setup information. TCP + TLS exchanges all the information needed for a reliable connection and encryption, validates it, and then exchanges data. QUIC just fires off the data immediately.

This process is explained in detail in the session ”How Secure and Quick is QUIC?” presented at the 2015 IEEE Symposium.

The presenter's swagger, hand in pocket, is hard to miss.

The key point of the video is this: TCP + TLS must exchange session keys and establish an encrypted connection before data can be exchanged with those session keys. QUIC can exchange data before session keys are even exchanged, which is why connection setup is faster.

However, when a client sends its first request to the server, it doesn’t yet know the server’s session key. So it encrypts the communication using an Initial Key generated from the destination server’s Connection ID. For a detailed explanation, see the QUIC working group’s Using TLS to Secure QUIC document.

Once a connection succeeds, the server caches the configuration and uses it for the next connection, enabling communication to start with 0 RTT. This is how QUIC achieves lower latency compared to TCP + TLS.

Note that this session was presented before TLS 1.3 was released, so it wasn’t mentioned. Today, using TCP Fast Open with TLS 1.3, you can achieve a similar connection setup process, giving TCP some of the same benefits.

However, TCP SYN packets are limited to about 1460 bytes per packet, while QUIC can include all the data in the first round trip. So for large payloads, QUIC still has the advantage.

Faster Packet Loss Detection

Like TCP, QUIC also needs flow control for transmitted packets. Both QUIC and TCP are fundamentally ARQ-based protocols — ARQ (Automatic Repeat Request) means recovering from errors through retransmission.

TCP uses “Stop and Wait ARQ”: after sending a packet, the sender starts a timer, and if the receiver doesn’t respond within a certain time, the packet is considered lost and retransmitted.

According to Google’s 2017 QUIC Loss Detection and Congestion Control, QUIC detects packet loss similarly to TCP but with several improvements.

A major issue with TCP’s packet loss detection is dynamically calculating how long to wait after sending a packet — when to trigger a timeout. This timeout is called the RTO (Retransmission Time Out), and the data it needs is a collection of RTT (Round Trip Time) samples.

You measure how long it takes to receive an acknowledgment after sending a packet, then dynamically determine the timeout. To measure RTT samples, you must receive an ACK from the sender. Under normal conditions this isn’t a problem, but when a timeout occurs and a packet is retransmitted, the RTT calculation becomes ambiguous:

Send packet → Timeout → Retransmit packet → ACK received!

(But is this ACK for the first packet or the second one?)

To determine which packet the ACK corresponds to, you need additional methods like timestamps on packets, plus extra packet inspection. This is called Retransmission Ambiguity.

To solve this, QUIC assigns a separate packet number space in its header. This packet number represents only the transmission order itself. Unlike sequence numbers (which remain the same on retransmission), packet numbers increase monotonically with each transmission, making it possible to clearly identify packet ordering.

With TCP, if timestamps are available, you can determine transmission order through them. If not, you’re left implicitly inferring order from sequence numbers. QUIC eliminates this unnecessary ambiguity through unique per-packet numbers, reducing the time needed for packet loss detection.

QUIC uses roughly 5 additional techniques to speed up packet loss detection. For details, I recommend reading Chapter “3.1 Relevant Differences Between QUIC and TCP” in QUIC Loss Detection and Congestion Control.

Multiplexing Support

Multiplexing is crucial because it prevents the HOLB problem mentioned earlier as a TCP drawback. With multiple streams, even if packets are lost in one stream, only that stream is affected — the others continue running fine.

Note that multiplexing doesn’t mean creating multiple TCP connections. It’s a technique for sending multiple data flows without mixing them up within a single connection. Each individual data flow is called a stream.

HTTP/1 used only one stream per TCP connection, so it couldn’t escape the HOLB problem. And since the connection closed after each transfer, you had to go through the handshake all over again.

The keep-alive option could maintain a connection for a certain time, but if there was no access within that window, the connection would still close.

HTTP/2 introduced multiplexing — handling multiple streams within a single TCP connection — to boost performance. With a single TCP connection carrying multiple data transfers, the number of handshakes dropped and data transfer became more efficient.

HTTP/3 supports the same multiplexing as HTTP/2.

QUIC also supports multiplexing like HTTP/2, carrying over these benefits. Even if one stream encounters a problem, the other streams are unaffected.

Connections Survive IP Changes

TCP identifies connections using the source IP and port plus the destination IP and port. If the client’s IP changes, the connection breaks. A broken connection means going through the tearful 3-Way Handshake all over again, adding more latency.

This is especially noticeable today because people frequently use mobile internet — switching from Wi-Fi to cellular, or moving between different Wi-Fi networks, all of which change the client’s IP.

QUIC, on the other hand, uses a Connection ID to establish connections with the server. A Connection ID is just a random value completely unrelated to the client’s IP, so even if the client’s IP changes, the existing connection is maintained. This means you can skip the handshake that would otherwise be needed to create a new connection.

Wrapping Up

To properly explain HTTP/3 and QUIC, foundational networking knowledge is essential, so there were parts that were hard to cover in depth in this single post. I tried to be as detailed as possible, but the post was getting quite long, so I had to trim things down.

After studying HTTP/3 and digging through various resources, my main takeaway was: “How did so much change?” Granted, once you throw out TCP, a lot is bound to change. But as someone who had only adopted HTTP/2 a few months earlier, it was a bit overwhelming. (The fact that they built HTTP but threw out TCP still blows my mind.)

Honestly, whether developers use HTTP/2 or HTTP/3, users in countries with excellent internet infrastructure might not notice much difference. The small geographic size and strong infrastructure can cover up handshake latency and then some. But in countries with weaker infrastructure, the difference could be quite significant.

In this post, I only talked about the advantages of HTTP/3 and UDP. Many people are concerned about abandoning TCP for UDP, and of course no technology is perfect — there will be issues.

But as an attempt to break through the limitations of existing HTTP and TCP, it seems like a great move.

That concludes this post on why HTTP/3 chose UDP.

References

관련 포스팅 보러가기

The Path from My Home to Google

Programming/NetworkWhy we need to know about CORS?

Programming/Network/WebSharing the Network Nicely: TCP's Congestion Control

Programming/NetworkTCP's Flow Control and Error Control

Programming/NetworkHow TCP Creates and Terminates Connections: The Handshake

Programming/Network