My Experience with Burnout, and How I Overcame It

To stop running on empty, I had to put down the whip I'd made myself

In 2018, I went through a severe bout of burnout. It’s a condition that even the WHO took seriously enough to officially register in ICD-11 in May 2019. The WHO says burnout isn’t classified as a medical disease, but rather as an occupational phenomenon.

Burnout is often described as “being completely burned out with nothing left but ashes.” When I first experienced it, that metaphor felt exactly right. This is something many people go through — the word “burnout” has become so commonplace that you hear it in everyday conversation.

What made my experience especially difficult was that it seemed to arrive without warning. One day I was enjoying coding, and the next morning I just… wasn’t. It was deeply unsettling.

Of course, burnout doesn’t actually appear overnight. It must have been building up gradually until some small trigger set it all off. Thoughts like “this is just what being an employee is like,” “the team is short-staffed so I have no choice,” and “if I don’t study on weekends, I’ll fall behind” — I’d been whipping myself with these every day, working overtime, pushing harder. It all accumulated until it couldn’t be contained anymore, and came back as one massive explosion.

So in this post, I want to reflect on what I felt during my burnout and how I dealt with it.

Burnout Came Out of Nowhere

As I mentioned, burnout seemed to hit me suddenly. It was the result of accumulated stress and pressure, but since I’d been accepting all of it as “just part of the job,” the shock was no less real.

The reason I first got into coding was simple — building things was genuinely fun, and being able to bring my ideas to life through code felt almost magical. I even formed a team called Rubicon with friends, and we’d build all sorts of projects together. During that time, we’d meet every day — weekdays, weekends, it didn’t matter — to discuss ideas and create new things. I was completely absorbed in the joy of it.

After graduating and working as a professional developer, I maintained this lifestyle for a few years. But as time went on, my patterns started to unravel.

Working until 11 PM was routine, but I’d still feel like the day was wasted if I went to bed then, so I’d code until 2-3 AM every night. On weekends, feeling like I needed to make up for lost time, I’d code from morning to night.

Then one day, sitting in the office coding as usual, a thought suddenly hit me:

This isn't fun anymore...

This isn't fun anymore...

I’d hit a wall — coding had become boring. At first, I thought it was because I’d been using the same framework (Vue) every day, so I switched to the mobile team that was using React Native. But the excitement of a new framework and development environment only lasted about a week. Once it became familiar, the same feeling of tedium returned.

This was something I’d started because I loved it, and the sudden loss of interest was a completely new experience for me. I had no idea how to cope. I still had to show up and do the same work tomorrow, and if my productivity dropped, it would affect the whole team.

On top of that, I was afraid to tell my teammates — worried that my negativity might drag down the team’s morale. I kept it bottled up. When I occasionally mentioned it to friends, the responses were typically “that’s just what working life is like” or “take a break.”

Since I was employed, I couldn’t just take an indefinite break. And no matter how much I rested on weekends, the tedium came right back on Monday. So I resigned myself to the idea that this is just how working life feels.

What I didn’t anticipate was that the burnout would get worse. Without proper intervention, the tedium deepened, and eventually I told my team lead that I wanted to quit.

At that point, my emotions were a complex mix: fatigue from the daily grind, guilt about being a burden to my teammates, and disappointment in myself for losing my love of coding.

I’ve always been impatient by nature, and I’d lived my life constantly driving myself harder. So my conclusion about the burnout was characteristically hasty: “It’s not getting better as fast as I expected — I should just quit before I drag the team down further.”

But my team lead told me something that changed my perspective: burnout isn’t an individual problem — it’s a team problem. He encouraged me to share what I was going through with the team anytime. That single statement meant more to me than he probably realized. It gave me just enough breathing room to start thinking differently.

From that point on, I began thinking less about code and more about myself — which led me to rediscover things I’d been overlooking for a long time.

Something I Never Experienced Before Becoming a Developer

Once I started seriously reflecting on myself to overcome burnout, the thing that puzzled me most was this: I had never experienced anything like this before becoming a developer.

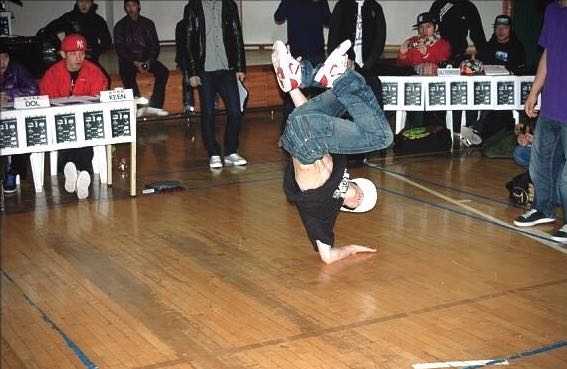

You might think that’s obvious since I was a student before, but from 2004 to 2011, I was actually a b-boy on a professional crew. So in a way, I was both a student and had a career at the same time.

A battle from almost 10 years ago — now just a memory

A battle from almost 10 years ago — now just a memory

And in case you’re not aware, the daily practice hours for competitive b-boys make a typical office worker’s schedule look relaxed.

On weekdays after school, I’d go straight to the practice room and train for about 6 hours until 10 PM. On weekends and school breaks, I’d practice from 9 AM to 10 PM — about 13 hours a day. If a performance or battle was coming up, I’d sometimes pull all-nighters practicing and go straight to school in the morning.

Honestly, it was physically and mentally harder back then. Yet strangely, I never experienced burnout during my b-boying years — only after I became a developer.

There were senior members who’d push me harder than any office boss, with blunter words too. I even got hit for not practicing hard enough. When I was learning a move called the airtrack, I couldn’t land two rotations, so for an entire year I spent over 5 hours every single day practicing nothing but that one move.

The airtrack — my love-hate nemesis. I never landed those two rotations before enlisting in the military.

So the question that consumed me during my burnout was: “Why didn’t this happen back then, but it’s happening now?” I figured there had to be a reason — if I’d endured far more grueling conditions without burning out, something fundamental must have been different.

The Whip I Made Myself

When I compared b-boy me to developer me, the key difference was this: as a developer, I was no longer satisfied with simply doing what I loved.

When I was b-boying, I genuinely enjoyed dancing for its own sake. I didn’t care about winning battles. I didn’t need anyone’s validation. This mindset stayed the same from day one through seven years of dancing. And during my active years on the crew, money didn’t really matter either (though that changed after military service).

But as a developer, I’d started caring about all sorts of things I didn’t care about before — being recognized for my skills, my salary, getting into a prestigious company. When these desires work in a healthy way, they can be a driving force for growth. But in my case, they’d gone too far.

After a long period of reflection, my conclusion was simple: “I’ve been whipping myself too hard.” No one outside was pressuring me. The desire for recognition, for more money, for a better company — these were all whips I had crafted myself.

Work Is Just Work

What I’ve always loved most about learning — not just coding, but anything — is the catharsis of finally understanding something I didn’t before. That feeling of becoming a better, more capable person. I kept chasing new knowledge to feel that rush.

As a junior, everything at work was new, so work alone provided that catharsis. But as the years went by, the feeling faded, and I started filling the gap by studying after work. Coding until 2-3 AM every night after work, however, began to take its toll.

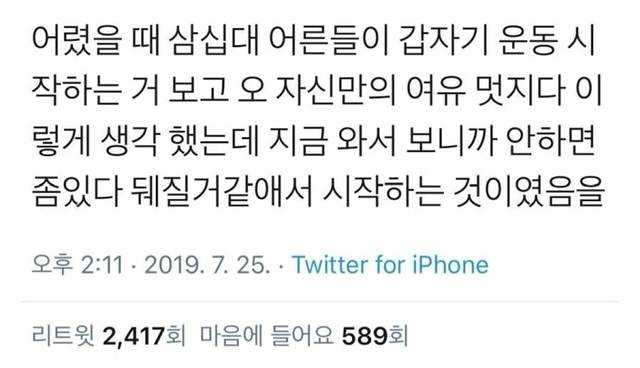

At 29, this meme was starting to hit a little too close to home.

At 29, this meme was starting to hit a little too close to home.

Whether it was accumulated fatigue, lack of exercise, or just getting older — at some point, I’d come home and just pass out. This led to a kind of obsession: since I couldn’t carve out time outside work, I needed to learn as much as possible while working.

So I started equating “working at the company” with “improving my skills.” Because of this belief that work must always make me better, the moment I realized that routine coding at work was no longer teaching me anything new, the tedium set in.

It didn’t take long to realize this thinking was flawed. The company is a client that contracts my expertise — there’s no rule that I must learn something new from every task. So I established a new principle:

The company is where I apply the knowledge I’ve honed — not a school for exploring new knowledge. I’ll do my job well for what I’m paid.

Some might see this as cold and calculating, but it’s also a mindset of taking responsibility for the salary you receive.

I still work overtime when needed and proactively suggest new ideas — but that’s part of the professionalism I provide in exchange for compensation. It’s voluntary, not something I do grudgingly because “that’s what employees are supposed to do.”

Once I shifted my thinking, my attitude toward work tasks changed from “this doesn’t benefit me” to “let me produce the best result I can with the skills I have.” I believe this shift both lifted a burden off my shoulders and made me more professional as a developer.

Letting Go of the Obsession with Skill

Another thing I committed to was “not coding every day.” While the world preaches the gospel of one-commit-a-day, I’d been doing ten-commits-a-day for over four years and that’s what led to this crisis. I figured some distance from coding was exactly what I needed.

This daily coding habit started in college. At first it was natural — I coded every day because I genuinely loved it. But at some point, it became half habit, half compulsive obligation.

Looking at the brilliant developers around me only amplified the pressure. I thought that if I slacked on learning new technologies and paradigms, I’d be left behind in this industry. So I kept reading tech posts and building projects with new tools.

In reality, no matter how much I studied, every technology has a learning curve, and keeping up with all of them is impossible. By the time you get comfortable with technology A, technology B with an entirely new paradigm has already emerged — that’s just how the IT industry works. I was essentially stressing over an impossible goal.

But when I thought about it more carefully, I realized I had plenty of unique strengths. Having dabbled in so many things over the years, I had knowledge in areas like WebGL, astrophysics, and sound engineering that most web developers don’t know or care about. (A jack-of-all-trades, if you will.)

Thanks to some active self-promotion, kind souls occasionally star my repositories.

Thanks to some active self-promotion, kind souls occasionally star my repositories.

These skills aren’t particularly useful for building typical applications, but when a niche role comes up that requires them, I can at least throw my hat in the ring. (And niche expertise tends to pay well.)

I started thinking of these as my unique weapons — what differentiated me from other developers. Ultimately, the mindset I had when I first started coding was the right one all along: don’t obsess over skill improvement — just study what you want to study and build what you want to build.

I still believe that skill is something that naturally follows when you build the things you want to build. The criteria for judging who’s “skilled” are so subjective and vague anyway that I decided to stop worrying about it and just live the way I want.

Salary? Not That Important

When I first got a job as a developer, I had a mental benchmark: “By 30, I should be earning at least X amount.” Thirty isn’t that old, but it was the first time the leading digit of my age would change since my teens, so I wanted to have something to show for it. (Looking back, I’m not sure why that mattered.)

I also believed that salary was the numerical representation of society’s recognition of my worth, which made me even more obsessed with it.

The problem was that I’m not a seasoned negotiator. Salary is largely determined through negotiation, and effective negotiation isn’t just about talking well — it requires sustained self-advocacy within the organization, peer evaluations, demonstrated skill, and frankly, a bit of luck.

Like being the last frontend developer standing after everyone else leaves — that’s the kind of fortunate situation that gives you leverage at the negotiation table.

Without much work experience, I couldn’t have known any of this, and naturally I kept drifting further from my unrealistic target. In hindsight it was obvious, but at the time I was anxious about falling behind.

My salary wasn’t particularly low or high. By any reasonable standard, it was enough for a 29-year-old to live on his own.

But human nature is fickle — even when you know you earn enough to live comfortably, seeing someone earn more than you inevitably sparks envy. The allure of money is powerful that way.

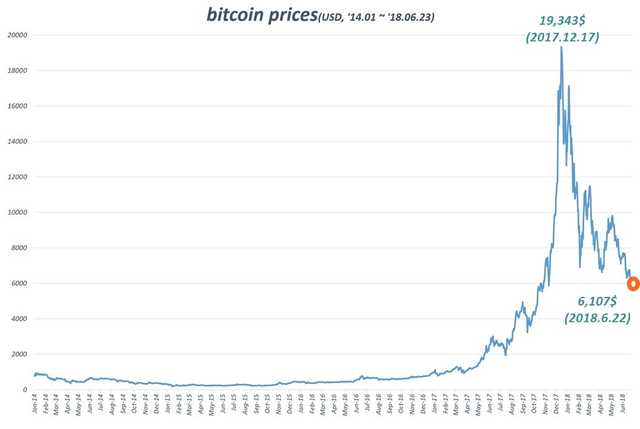

This led me to question whether salary was really that important. My conclusion was: no matter how much I earn, it’ll never feel like enough. When I told friends this, some asked if I’d become a monk. But it wasn’t some spiritual epiphany — I just ran the numbers.

When I factored in my income since my first job, monthly expenses, and average annual raise, and projected ten years out… the picture wasn’t exactly inspiring. Saving maybe 300K by my 40s would be doing well. Some might say that’s a decent sum, but I figured the difference between saving 300K wouldn’t fundamentally change the trajectory of my life.

For an ordinary person like me — unless I win the lottery or hit it big on stocks or crypto — the reality is earning what I can, taking out loans to buy a house and a car, and living more or less like everyone else. It might sound bleak, but that’s what the calculator showed me about life as a salaried worker.

An ordinary person like me doesn't have the courage or the luck to ride that wave.

An ordinary person like me doesn't have the courage or the luck to ride that wave.

Once I reached this conclusion, getting worked up over a few thousand dollars in annual raises started to feel pointless. These days, I don’t particularly care whether my salary goes up or not. Of course more money is always nice, but if it doesn’t happen, I don’t stress about it — “it’ll go up eventually.”

Besides, the joy of a raise wears off in a few months once you get used to the new number anyway.

The funny thing is, adopting this mindset didn’t make me earn less. As the years passed, my salary did increase. I published a book. My blog started generating a little income. I’m actually earning more now than before. So it seems like if you just focus on doing your work well, the money follows naturally — regardless of whether you obsess over it.

Reconsidering all these self-imposed pressures helped me shed a lot of the weight I’d been carrying around my work as a developer.

Find Hobbies Outside of Coding

Another thing I realized was important: remembering who I am beyond “developer.” For four years, I’d been so immersed in coding that I had virtually no hobbies or cultural life. Everything in my daily existence revolved around code.

Burnout was certainly fueled by pressure and stress, but I also think it happened because I’d lost touch with who I fundamentally was as a person. This probably isn’t unique to developers — it’s something many working professionals experience when day-to-day work consumes everything.

As I put “not coding every day” into practice, I started filling the freed-up time with things I actually enjoyed. Writing this blog is one of them, but the biggest one was music.

I’d actually studied music consistently since childhood. I’d even prepared for music composition college entrance exams (though I gave up after being intimidated by the truly talented), and worked as a sound engineer at an entertainment agency. Music has always been a big part of who I am.

My happy grasshopper days as a professional sound engineer

My happy grasshopper days as a professional sound engineer

But once I started working as a developer — coding day and night, weekdays and weekends — music gradually fell away. I still listened to music daily, but analyzing compositions, practicing instruments, studying music theory — all of that got deprioritized until I just stopped doing it.

So the first thing I did when I committed to overcoming burnout was dusting off the piano at home. Since then, I’ve been consistently playing piano and guitar, taking vocal lessons, and studying music theory as a hobby. (As a result, my nickname at work became “the grasshopper” — a reference to the fable about the carefree grasshopper who plays music all day.)

Music is a lifelong hobby you can enjoy at any age, so I’d recommend everyone learn at least one instrument in their lifetime.

Wrapping Up

The reason I couldn’t practice any of the things I mentioned above before my burnout was fear — fear of falling behind, and the pressure to become a developer recognized for their skills. With barely enough hours to code and study each day, hobbies and leisure felt like luxuries I couldn’t afford.

But all those self-imposed whips eventually came back as burnout. The relentless self-discipline did help me grow quickly in a short time, but looking back, I wonder if it was really worth it.

These days, I don’t follow trends much. I study things when I need to or when I’m curious — so I’m definitely slower at picking up new tech than I used to be. I didn’t even hear about Kubernetes until well after everyone else had started using it, because a friend happened to mention it.

But I can at least say that I’m happier doing development now than I was before.

The reason I started coding in the first place was simply because it was fun. And the value I hold most important as a developer today is still fun. Since that value isn’t something a great mentor or a prestigious company can give me, I’ve stopped worrying about my surroundings.

At the time of writing this, I’ve actually signed a freelance contract with a Korean company and I’m living in Prague, Czech Republic — doing a bit of digital nomad life. The courage to make that leap — accepting a month-long gap and the not-insignificant costs for someone between jobs — was something that grew directly out of this burnout experience.

A lovely café that doubles as a coworking space.

A lovely café that doubles as a coworking space.Highly recommended for anyone digital nomading in Prague.

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t worried before coming to Prague, but with nothing to lose as someone between jobs, I just went for it. After three weeks here, well — none of the things I worried about have actually been problems.

After leaving my company, a few people reached out about job opportunities. Since I was leaving for Prague two weeks after my last day, I had to put those conversations on hold. Honestly, I expected the interest to fizzle out while I was away in Europe for a month.

But thankfully, I’ve kept in touch with several of them, and the freelance work from Korea has kept a steady income flowing. Plus, the cost of living in Prague turned out to be surprisingly affordable, so my expenses have been low. Then again, I’m not exactly traveling around — mostly just taking walks around the neighborhood.

Would the old me have been able to make the decision to spend a month in Europe? Probably not. I would have thought that a month away meant falling behind.

The burnout was painful, but in the process of letting go of unnecessary burdens, I ended up living a healthier life as a developer than before. Coding became fun again. Rediscovering my strengths gave me confidence I’d lost. And I got to have this wonderful experience of living abroad for a month.

That wraps up this post on my experience with burnout and how I overcame it.