Do Developers Need to Be Good at Math?

Math is just a tool — good developers grow through logic

In this post, I want to address one of the questions I get asked most frequently: “Do developers need to be good at math?” This is a topic that divides developers worldwide, so please take this as just one developer’s perspective.

I’m not particularly good at math myself. Like most CS grads, I studied it in school but can barely remember any of it after graduating. I’m especially terrible at manual calculations. (I mess up basic arithmetic all the time.)

Still, since many people discuss this topic online, and I’ve been asked about it by non-developers too, I figured I’d share my thoughts.

Programming Is Math

Fundamentally, the computer we use is just a calculator that works with 0 and 1. So naturally, computers are steeped in mathematical concepts, and programming is full of mathematical ideas whether we realize it or not.

That’s why I believe developers should know at least some math. If you’re thinking “wait, I’m not good at math but I’m a working developer” — hear me out.

The math I’m talking about isn’t advanced topics like linear algebra or calculus. I’m talking about things like propositions, sets, and number bases — concepts we already learned in middle and high school.

Sure, these concepts get increasingly abstract and complex the deeper you go, but honestly, you don’t need to go that deep. We’re not mathematicians — as developers, we just need to know enough for programming. The important thing is not to be intimidated by the word “math.”

So in this post, I want to lightly cover three mathematical concepts that I think are genuinely helpful for programming.

Don’t Be Intimidated by Math!

Hot topics like machine learning and neural networks are certainly intriguing, but the moment you Google them, the search results crush your motivation.

…

When the solution depends on some data, the cost must be a function of the observations; otherwise nothing related to the data can be modeled. In many cases the cost is given only as a statistic that can be approximated.

As a simple example, consider the problem of finding the model that minimizes the cost for data pairs drawn from some distribution . In practice, we can only draw a finite number of samples from the distribution , so in this example only the cost over the sample, , can be minimized.

…

I'm supposedly looking at math, but I see more Greek letters than numbers...

I'm supposedly looking at math, but I see more Greek letters than numbers...

Honestly, when you first see equations like that, they look like an alien language. And what they describe as a “simple example” doesn’t look simple at all.

This is exactly what kills our motivation to study math. But is that equation really that complex and difficult?

If you just know what those symbols and letters mean, you can port the equation to code — and once you do, it turns out to be remarkably simple. Let’s try writing the most intimidating-looking part, , as code to compute the value C.

const inputs = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10];

const outputs = [10, 9, 8 ,7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1];

const N = inputs.length;

function exampleFunction (x) {

return x + 1;

}

function getC (x, y) {

let result = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < N; i++) {

result += (exampleFunction(x[i]) - y[i]) ** 2;

}

return result / N;

}

const C = getC(inputs, outputs);There — now that equation should make a lot more sense. Even if you didn’t understand the mathematical notation, you can understand the code.

Let’s start with the intimidating-looking .

The symbol (read “sigma” or “sum”) simply means “loop through and add up the values that follow.” So means “initialize to 1, iterate up to , and sum the values.” The variable i we conventionally use in for loops actually comes from this mathematical convention.

Once you know that, and in make sense naturally — they just refer to the -th element of some collection.

And the multiplied at the end? When you sum values over iterations and then divide by , what do you get?

Yes, the average.

After seeing this, that equation shouldn’t feel so foreign anymore. And as I said, my point isn’t about whether you can write the equation as code. My point is that even equations like this turn out to be straightforward once you translate them to code. There’s no need to be intimidated!

We’re simply more familiar with for loops than with the symbol. If you encounter an unknown symbol in an equation, look up what it means. Some symbols do represent inherently complex concepts. (Like the integral symbol …?) But in most cases, letters are just variables, and symbols represent rules (like programming statements) or special functions. Break them down one by one and translate them to code — you’ll find they’re simpler than you expected.

Now that we know math isn’t as scary as it seems, let’s stop fearing the word itself and dive in.

Three Math Concepts That Help with Programming

Now for the main topic: three mathematical concepts that are helpful when programming.

What I want to discuss are concepts rather than equation-heavy algebra like the example above. These concepts are actually closer to logic than to math, so you don’t need to think of them purely in terms of numbers.

These are concepts we already learned in middle and high school. We just forgot them because there wasn’t much use for them after standardized tests. Those who majored in STEM or math-heavy fields like economics might still remember, but for everyone else, forgetting is only natural.

These are all logic concepts you’ve encountered at least once as a kid, so let’s approach them with a light heart.

Propositions

The first concept is propositions — something we learned in middle school. Propositions aren’t just useful for programming; they’re fundamental to logical thinking in general.

A proposition is a statement that has a logical truth value — true or false. Statements where truth and falsehood can’t be determined don’t count as propositions. “Gildong is tall” isn’t a proposition because tallness is subjective — someone might think he’s tall, someone else might not.

So where do propositions show up in programming?

The true and false of propositions are the exact same concept as True, False or 1, 0 in programming. In other words, the propositions we learned from math textbooks in middle school are equivalent to conditional expressions. Let’s look at a simple example:

const array = ['a', 'b', 'c'];

if (array.includes('a')) {

console.log('The array variable contains a.');

} else {

console.log('The array variable does not contain a.');

}The proposition I’ve presented here is “the array stored in the array variable contains the element a.” If this proposition is true, the code inside the if block executes; if false, the else block runs. Since conditions used in conditional statements must be propositions, a developer comfortable with propositions can quickly formulate the right conditions when hearing a requirement.

Propositions are the most fundamental concept underlying everything else I’ll discuss — and all other mathematical concepts too. That’s why we learn them at the very start of middle school. Mathematics isn’t a wishy-washy discipline; it requires the ability to ask precise questions and provide precise answers, which is why propositions form its foundation.

Sets

Next up is sets, also learned in middle school. Like propositions, sets are used constantly in programming without us always realizing it — so having a solid understanding of them is genuinely helpful.

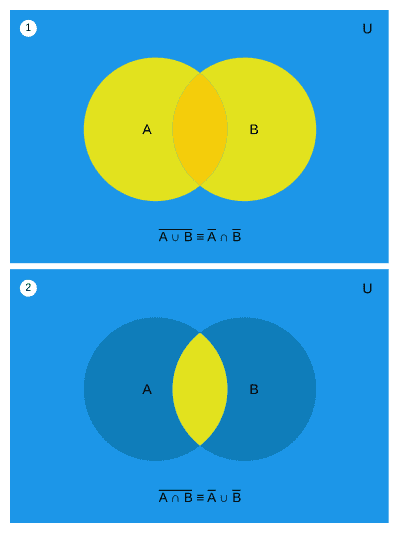

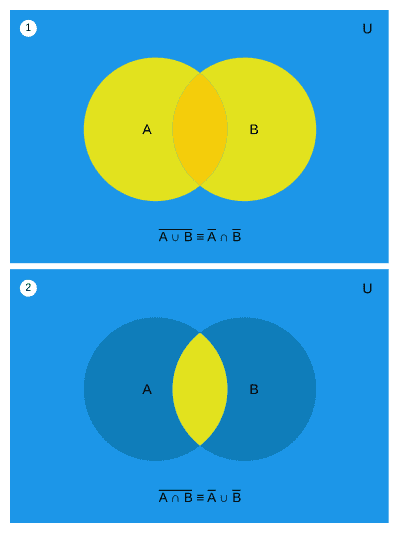

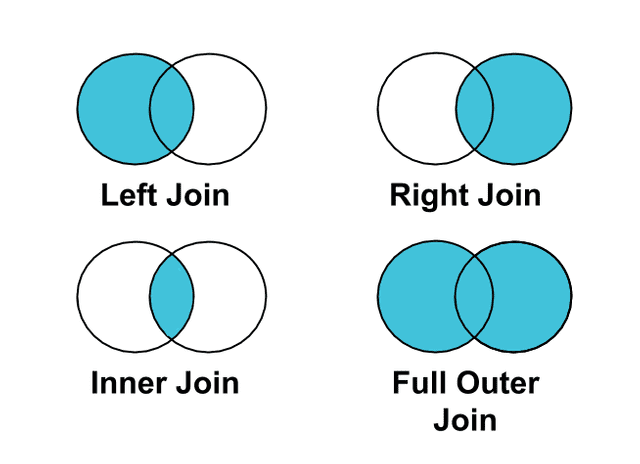

Those cute round Venn diagrams might seem far removed from programming, but we actually use the concept every single day — when writing logical expressions. A logical expression, like a proposition, evaluates to either True or False. We typically combine multiple propositions using logical operators. So what do logical expressions have to do with sets?

The logical operators we use map directly to set operations: && (AND) = intersection and || (OR) = union. This means that when you encounter a complex logical expression, you can draw it as a Venn diagram. And De Morgan’s laws, which we memorized as kids, apply directly to logical expressions too. (De Morgan’s laws are actually more broadly a law of logic than strictly about sets.)

De Morgan's laws represented as Venn diagrams

De Morgan's laws represented as Venn diagrams

I think De Morgan’s laws really shine when converting natural language into logical expressions. In business logic development, POs frequently add conditions to how features should behave — but the problem is they rarely consider all the existing conditions when adding new ones.

Let me give an example of the most complex condition I’ve ever encountered at work. I once developed a membership payment feature where the rendering conditions for the payment method form became absurdly complex. It didn’t start that way — it grew complicated as features were added over time.

Here’s what the conditions looked like in natural language:

Condition 1: The user’s membership is not cancelled AND they don’t have a registered payment method. Condition 2: The user has a payment method AND it’s a mobile payment AND the product they’ve selected is different from their current product AND their membership is not in a scheduled cancellation state.

If

(Condition 1 || Condition 2), the payment method registration form is activated.Conditions version 1

Admittedly, this mess was primarily my fault as the developer, but if I had to make excuses — I was working overtime every day under time pressure, and that’s how this monstrous logical expression was born…

After creating this mess, I had too many other things to do, so I buried it and moved on to the next project. Then the PO came to me:

Hey Evan, can we add one more condition to the payment method registration form?

After hearing that, looking at the code, looking at the PO’s face, and concluding that I needed to untangle this somehow, I quietly took my laptop to the whiteboard and fought to make those complex conditions comprehensible. The result:

Condition 1: The user doesn’t have an active membership AND their registered payment method is not a card. Condition 2: The user has an active membership AND their registered payment method is mobile AND the membership they’re trying to purchase is a different product from their current one. Condition 3: The user has no payment method information.

If

(Condition 1 || Condition 2 || Condition 3)AND the user’s selected payment method is a card, the payment method registration form is activated.Conditions version 2

It’s still not a simple logical expression, but at least reading conditions 1, 2, and 3 individually gives you a much clearer picture of what state each describes compared to before. (At least that’s what I tell myself.) The tools I used to simplify this were Venn diagrams and De Morgan’s laws.

By spreading the logical expressions out as Venn diagrams, I could easily spot propositions that were actually the same but written in contrapositive form. I identified overlapping propositions, merged them, and split conditions into more comprehensible units.

Of course, this code still needs to be improved someday… (Someday…)

Beyond logical expressions, SQL’s JOIN concept is also commonly represented with Venn diagrams.

If a Venn diagram pops into your head immediately when you see a complex logical expression or SQL JOIN, wouldn’t you understand it more intuitively and quickly than processing raw code or natural language?

Mathematical Induction

Mathematical induction is a proof technique used in mathematics, primarily to show that a proposition holds for all natural numbers. Before diving into what mathematical induction is, we need to understand the two main types of logical reasoning: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Simply put, inductive reasoning feels like “it’s been this way so far, so it’ll continue to be this way,” while deductive reasoning feels like “if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true.” I’ll keep this brief with simple examples.

Inductive reasoning goes like this:

The summer of 2000 was hot. The summer of 2001 was hot… The summer of 2019 was hot. Therefore, summers are always hot.

Even if every premise is true, the conclusion isn’t guaranteed to be true. In the example above, couldn’t an extreme weather event bring snow in the summer of 2020? (The Day After Tomorrow…?)

In other words, inductive reasoning always carries a probability of error. It might seem full of holes, but modern science has advanced through inductive reasoning — continuously proposing and proving hypotheses — so it’s quite valuable.

Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, goes like this:

MacBooks are made by Apple. My computer is a MacBook. Therefore, my computer was made by Apple.

This is a syllogism — the most classic example of deductive reasoning. This is what “if certain premises are true, the conclusion must be true” means. If the conclusion is false, at least one premise must also be false. Deductive reasoning excels at proving what’s already contained in the premises, but unlike inductive reasoning, it’s not suited for exploring new knowledge.

In programming, we’re not exploring new knowledge — we’re trying to prove our code is correct and error-free. So deductive reasoning is more appropriate than inductive reasoning.

The reason I explained both is that mathematical induction, despite its name, is actually deductive reasoning, not inductive.

Wait... you said induction...?

Wait... you said induction...?

Mathematical induction means that if a proposition satisfies these two conditions, then holds for all natural numbers:

- is true.

- If is true, then is also true.

Therefore, proposition is true for all natural numbers.

That might make your head spin, so let’s look at an example. Mathematical induction is usually illustrated with dominoes, so I’ll do the same.

- The first domino falls. ( is true)

- Whenever a randomly chosen -th domino falls, the -th domino always falls too. (If is true, then is true)

Therefore, if you knock over the first domino, all dominoes will sequentially fall.

This is the logical structure of mathematical induction. In simple terms: you first show that the premise is true, then derive a universal conclusion from that premise.

Mathematical induction is extremely useful for verifying the correctness of algorithms. Algorithms are by nature universal rules that always contain some form of repetition.

Let’s apply mathematical induction to the classic factorial algorithm:

function factorial (n) {

if (n < 1) {

return 1;

}

else {

return n * factorial(n - 1);

}

}

- When , .

- .

- .

Therefore, this logic is correct.

This kind of logical thinking may not directly help you while coding, but it builds the ability to find generalized solutions when facing complex problems. Problems where these reasoning techniques apply are everywhere in daily life, so it’s not a bad habit to start thinking this way.

Wrapping Up

Honestly, you can be a perfectly good programmer without knowing any of this — just going by intuition and feel. But think about it: even those who thought they didn’t know this stuff were probably using all of these concepts unconsciously. They just hadn’t formalized them as theory.

And I think the best thing about learning math is that when you want to build something, at least the theory won’t be what stops you.

Looking at posts I’ve written before, like calculating planetary orbits or the backpropagation algorithm, they might look intimidating with all the equations. When I first built those projects, the math I’d learned in school was already hazy, so I essentially studied it all over again from scratch — and eventually completed those projects.

Theories with terrifying names like linear algebra, Euler rotations, and quaternions were certainly daunting at first. But by keeping at the documentation even when I didn’t understand, writing code for the parts I could grasp, and running it line by line to see the mechanics with my own eyes — at some point, things started becoming much more familiar.

Math isn’t as scary as it seems. Just like that neural network equation looked complex and intimidating at first glance but turned out to be straightforward once translated to code. As developers, mathematical and logical concepts are already ingrained in us whether we know it or not — so isn’t it a bit silly to be afraid of math at this point? Let’s drop that fear and befriend math.

Think of math as just another tool — like a programming language — that can bring your imagination to life.

That wraps up this post on whether developers need to be good at math.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Why Do Type Systems Behave Like Proofs?

ProgrammingHow Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/ArchitectureSimplifying Complex Problems with Math

Programming/Algorithm[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Implementing Planetary Motion

Programming/Graphics