Is Data-Driven Decision Making Really Flawless?

The traps hidden behind numbers, and how not to be fooled by data

In this post, I want to talk about data-driven decision making. The concept started gaining traction around 2013, riding the wave of the big data hype. Many companies already use it as their go-to decision-making method, and there are plenty of success stories backing it up — so it’s earned a fair amount of credibility.

That is, only when you truly understand the nature of data.

Is data-driven decision making really as trustworthy as the world makes it out to be? Actually, before that — what does “the nature of data” even mean?

What Is the Nature of Data?

We tend to treat data and information as the same thing. But data, by itself, is not information.

Data is simply a value obtained by observing the real world. It’s just a value — nothing more, nothing less.

Information, on the other hand, is what you get when you process data in some way to create something meaningful. The process of turning data into information is what we call data mining.

This sounds like something out of a textbook, so let me put it in simpler terms. Say the forecast tells you tomorrow’s average temperature will be 28°C (82°F). The fact that it’ll be 28°C is data — a raw observed value. Whether it came from a supercomputer or AlphaGo, it’s still just an observed number at this point.

Now, hand this data to someone who plans to stay home all day. Does it matter to them? Unless they don’t have air conditioning, probably not. It’s essentially a meaningless value.

Why would you care how hot it is outside if you’re not going anywhere? Just turn on the AC and eat some watermelon.

Whether it's 28°C outside or not, as long as you don't leave the blanket, it doesn't matter.

Whether it's 28°C outside or not, as long as you don't leave the blanket, it doesn't matter.

But give that same data to someone who has to commute across the city tomorrow, and suddenly it becomes critically important information — potentially a matter of survival. (I’m exaggerating a bit because I’m terrible with heat.)

It’d be nice to also show a friendly message like “If you wear long sleeves tomorrow, you might not make it — be careful! ^^“. In other words, data by itself doesn’t mean much, but depending on the situation and the reason it’s being used, its informational value can vary enormously. That’s the nature of data.

How Is Data Collected?

So how does data-driven decision making actually work?

Nothing fancy. You just collect data — relentlessly. A massive stockpile of data is valuable enough to be considered a company asset on its own. If you have data, you can process it however you want. Without data, there’s nothing to process.

You’re Being Stalked Without Knowing It

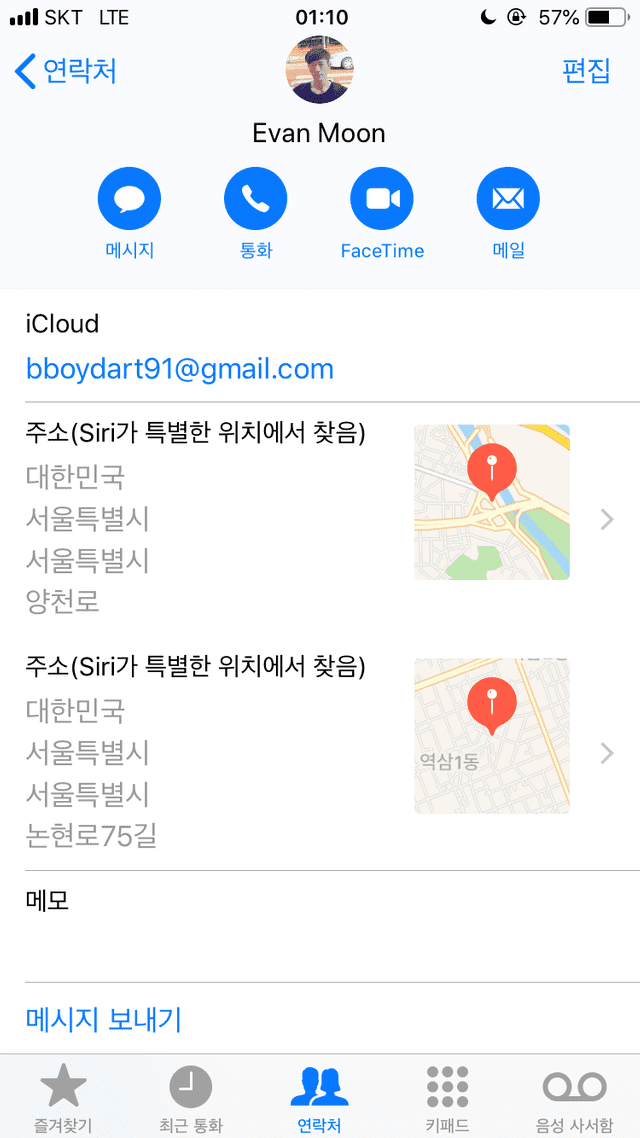

Apple and Google — the companies that essentially rule the smartphones glued to our hands — also quietly collect your data. If you’re an iPhone user, try tapping your profile at the top of the Contacts app and scrolling down. You’ll likely find an “Addresses (found by Siri at notable locations)” section with your home or workplace saved there.

As another one of Apple’s loyal subjects, I’m being tracked by Siri as well. My home is actually somewhere in Gangseo-gu, Seoul, and the second address shown is my office.

Whether Apple actually stores this on their servers, I’m not sure — but the point is that companies are collecting your data in real time, right this moment. And it’s not just tech giants like Apple or Google. Even startup-sized companies track all of your behavioral data. Companies use solutions like Google Analytics, Amplitude, Mixpanel, and Hotjar to accumulate your behavioral data and leverage it for decision making.

At this point, you might be thinking:

I'm always watching you...

I'm always watching you...

That’s right. You’ve been feeding companies high-quality data without even realizing it. It reminds me of Big Brother from George Orwell’s 1984.

Of course, governments don’t just sit idly by. In many countries, regulations like the GDPR in Europe or various data privacy laws require companies to anonymize personal data — stripping out individually identifiable information and keeping only the data they actually need.

The key principles generally include:

- (Preliminary review) Determine whether the data constitutes personal information; if clearly not, it can be used freely.

- (De-identification) Remove or replace elements that could identify individuals in datasets.

- (Adequacy assessment) Evaluate whether the data could be easily combined with other information to re-identify individuals.

- (Post-management) Monitor for re-identification risks and take necessary safeguards during data use.

That said, these regulations can be complicated, and enforcement varies — so in practice, many companies likely continue business as usual. Still, any legitimate company should have a privacy policy that explains what personal data they collect, why, and how they use it. It’s worth reading, even if it’s tedious.

Now for the Data-Driven Decision Making!

Data-driven decision making is essentially about analyzing the collected data to draw plausible conclusions.

It’s naturally less risky than making decisions based on pure gut feeling, since you’re at least working with observed values. This approach is especially popular in marketing — specifically in personalized advertising systems that recommend products you’re likely to be interested in.

Personalized ad systems collect your behavioral data as you browse the web, analyze what you’re interested in, and then serve ads that match. It’s a form of data-driven decision making. Targeting products that someone is likely interested in obviously yields much higher conversion rates than showing random ads.

Let’s first look at some advantages of data-driven decision making.

Advantages of Data-Driven Decision Making

There are many advantages, of course. I can’t list them all, so I’ll just highlight a few that I think are most notable.

Minimizing Uncertainty

The most straightforward advantage is reduced risk from decision-making. As I mentioned, basing decisions on analyzed observational data is inherently less risky than relying on intuition alone.

Easier to Persuade Others

The second advantage is that it’s much easier to convince people. I think there’s a psychological element at play here. A presentation with polished graphs, tables, and numbers just feels more credible than words alone. This is probably more relevant for roles like designers — who rely heavily on intuition — than for developers who are already comfortable with logic and numbers.

a. From a UX perspective, placing this button here would make it easier for users to discover!

b. Our user testing showed that 78% of users only interacted within the top 20% of the page before leaving. Therefore…

It comes down to the difference between these two approaches. Fellow designers might understand each other intuitively, but when communicating with other roles — POs, CEOs, engineers — the latter is clearly more persuasive. Of course, blindly trusting those numbers is dangerous. But if the data collection method and experimental conditions were sound, it’s a perfectly valid approach.

Clear Expectations and Outcomes

When you plan features based on data, you go in with expectations like “if we build this feature, users will do more of X.” After shipping, you can analyze whether that behavior actually increased and by how much — making outcomes easy to measure.

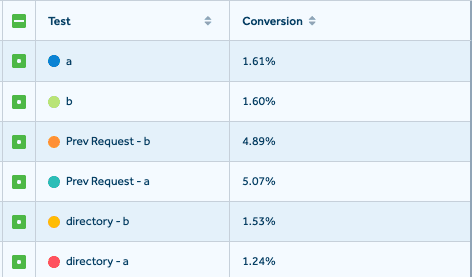

A/B testing lets you verify whether a deployed feature actually produced the desired results.

A/B testing lets you verify whether a deployed feature actually produced the desired results.

Simplifying Complex Problems

Personalized advertising, as described above, is actually a very complex problem. Representing something as abstract as human interests numerically is no easy feat. But “not easy” doesn’t mean impossible.

For example, when I was recently interested in a certain e-cigarette brand, I went around reading reviews on blogs and YouTube, and visited online vape shops to see what accessories were available.

My browsing history undoubtedly contains multiple hits for the keyword “e-cigarette.” Collecting this keyword and serving me e-cigarette-related ads isn’t rocket science.

This is how a complex problem like “figuring out what this person is interested in” can be reduced to simple keyword matching — another advantage of data-driven decision making.

Disadvantages of Data-Driven Decision Making

So far, data-driven decision making sounds like a flawless approach — low risk, measurable outcomes, and the ability to simplify complex problems!

Nope.

Nope.

Data-driven decision making does have many strengths, but if you don’t properly understand the nature of data as discussed above, you can end up making decisions that are completely disconnected from reality. Here are the points I think people most commonly miss.

Data Is Just a Value

As I said earlier, data is simply a raw value. That means when you analyze data to extract meaningful information, human subjectivity inevitably enters the picture.

In most organizations, data analysts play this role, and their intuition plays a significant part. In fact, how accurate their intuition is essentially defines their skill.

The key point is that results derived from data are ultimately information filtered through human subjective judgment. When you put too much faith in data-driven decisions, it’s easy to think:

The results are based on values we directly observed, so the conclusions must be accurate too!

But accurate data doesn’t guarantee accurate conclusions. You must always view results with a critical eye. And by “critical eye,” I mean the habit of asking “why” — why did this result turn out this way?

Blind Faith in Data Can Lead to Bad Decisions

Data only describes what happened — it never tells you why something happened. So the question “why did we get this data?” is typically left to expert intuition, or answered by investing more effort into collecting qualitative data.

So why is it dangerous to make decisions based only on what happened, without considering the reasons?

Causation vs. Correlation

Causation and correlation are among the most fundamental concepts in statistics. I’ll keep the definitions brief since this could go on forever.

Correlation means that when one statistical variable increases, another variable also increases or decreases. If variable decreases and variable also decreases or increases in tandem, they’re correlated. If the two variables move independently with no pattern, they’re uncorrelated.

The degree of correlation is expressed as a correlation coefficient. A coefficient close to 0 means little correlation, close to -1 means strong negative correlation, and close to 1 means strong positive correlation.

Causation, on the other hand, is when a preceding variable is determined to be the cause of a subsequent variable.

Consider the statement “the more it rains, the higher the river level rises.” While there may be other hidden variables at play, rainfall is almost certainly a major cause of rising river levels — so we’d call this a causal relationship.

But “the closer it gets to summer, the higher the river level” is merely a correlation. The river level rises in summer because roughly 70% of annual rainfall is concentrated in the summer months — not simply because it’s summer.

In business, most variable relationships are correlations, so you should always consider whether there are hidden variables and maintain a healthy skepticism about whether the results are truly reliable.

Examples of Bad Decisions

To illustrate what happens when you blindly trust data, here are two classic examples commonly used to demonstrate the dangers of data.

A researcher was examining the seasonal trends in ice cream sales throughout the year. They also plotted the seasonal trends in drowning deaths alongside it and ran a correlation analysis between the two datasets.

The results were striking.

There was an unmistakably clear correlation. During periods when ice cream sales increased, drowning deaths also increased. When ice cream sales decreased, drowning deaths decreased as well.

Shuddering at the implications, the researcher drew the following conclusion:

“Ice cream is the cause of drowning deaths.”

In this example, the researcher is essentially saying “the more ice cream is sold, the more people drown.” It sounds absurd, but ice cream sales and drowning deaths do in fact correlate.

The hidden variable here is temperature. When summer arrives and it gets hot, ice cream sales go up. At the same time, more people go to beaches and rivers for vacation, so accidental drowning deaths also increase.

If you failed to identify temperature as the hidden variable, you might end up with a decision like this:

To reduce drowning deaths, we ban ice cream sales.

Now for the second example. This one comes from a TED 2017 talk by mathematician and data scientist Cathy O’Neil. I personally found this talk fascinating.

Cathy O'Neil presenting at TED

Cathy O'Neil presenting at TED

Fox News, founded in 1996, decided to adopt a machine learning algorithm to streamline their hiring process.

For training data, they could use 21 years’ worth of applicant data from Fox News. They also needed to define “success” to identify candidates likely to thrive at the company. Let’s say someone who worked at Fox News for at least four years and got promoted at least once counts as successful.

Now, what happens when you apply this algorithm to current applicants?

No female applicant would ever pass.

I was personally shocked when I first heard this example. When the story began — using 21 years of applicant data and defining success as working four years with at least one promotion — it sounded like a perfectly fair and objective metric.

But true gender-blind hiring based solely on merit is a relatively recent development in our society. Under the rules defined above, the absolute number of “successful” people at Fox News would inevitably skew male. Add to that Fox News’s conservative orientation, and the bias would be even more pronounced.

The hidden variable in this example was the social climate of the times.

No matter how objective you think your metrics are, if you don’t ask “why did we get these results?” before making decisions, you can end up with conclusions that are completely divorced from reality.

Don’t Ignore Qualitative Data

When most organizations make data-driven decisions, they focus on quantitative data rather than qualitative data.

The reason is simple: quantitative data is easier to collect, compare, and process — the data mining workflow is more straightforward. Qualitative data, on the other hand, requires more deliberate methods like user testing and surveys.

Moreover, qualitative data often comes in the form of natural language rather than numbers, making it harder to analyze.

For these reasons, I’ve often seen qualitative data get deprioritized — but that’s not a good practice. Quantitative data explains what happened; qualitative data explains why.

For example, the difference looks like this:

After users engaged with our search system, the conversion rate increased by 30%. (Quantitative data)

Survey results showed that users felt they could find products that better matched their needs by searching on their own. (Qualitative data)

You could technically convert that qualitative example into quantitative data — by using multiple-choice questions instead of open-ended ones. But then you can only capture the reasons you’ve already thought of, which is why most surveys include an “Other (please specify)” option. And whatever people write in that box? That’s qualitative data.

Just think about it: the “Other” field will contain natural language that people took the time to write out individually, and classifying and analyzing all of that requires either artificial intelligence or a lot of human effort.

That’s why most companies lean toward easier-to-handle quantitative data and use qualitative data as supplementary. But companies that genuinely want to hear what their customers want invest the resources to continuously collect qualitative data through surveys and user testing, even when it’s costly.

At my workplace, we don’t have the resources to do it frequently, but for major feature launches, our UI/UX designers invite users who match selected personas to the office for user testing sessions.

Wrapping Up

I think data-driven decision making is a double-edged sword. Used well, it delivers the advantages I described — lower risk, clear outcome measurement, and the ability to abstract complex problems. Used poorly, you end up blindly trusting numbers without realizing something has gone wrong, making bad decision after bad decision.

The “clear expectations and outcomes” advantage can also become a disadvantage. As I’ve repeatedly emphasized, data is ultimately just raw values, and the conclusions drawn from it inevitably involve human subjectivity. This means you can predetermine the result you want and massage the data to fit — producing conclusions that look perfectly plausible.

These tendencies can lead to decisions that optimize for metrics the company considers important rather than actually serving customers. Or worse, someone might manipulate variables until they get the result they want — even if customers are dissatisfied and conversion rates are dropping — all to earn recognition from higher-ups. It becomes a political tool rather than an analytical one.

These behaviors aren’t data-driven decision making — they’re number games dressed up as data-driven decision making.

That’s why, whenever you make data-driven decisions, you must constantly ask yourself: Did I reach an objective and fair conclusion? Is this data truly uncontaminated and capable of yielding meaningful results? If the results came out as I hoped, why did they turn out this way? Maintaining this critical mindset is essential.

That wraps up this post on whether data-driven decision making is really as flawless as it seems.