Vue Server Side Rendering

Vue SSR Rendering Process and Practical Construction, Operation Experience

In this post, following Universal Server Side Rendering, I want to write about the process of developing an SSR (Server Side Rendering) application using VueJS’s official library vue-server-renderer and Express, problems that arose in the production environment, and how those problems were solved.

As a Frontend developer, I actually rarely had occasion to touch Backend frameworks. However, since I advocated introducing the SSR server at my current workplace, and therefore ownership also belonged to me, I needed to know in detail about server operation methods and various problems that are completely different from client environments.

Usually Frontend developers develop applications operating on clients, so I think they can unexpectedly easily miss and pass over problems that can occur in applications operating on servers (obvious if you think a bit).

So I want to organize into documents and reflect so I don’t repeat these mistakes twice.

First I’ll look at Vue SSR’s rendering process overall, then examine server-side rendering and client-side rendering separately.

Code appearing as examples in this post may not work even if copy-pasted because parts are omitted due to current workplace business logic.

Structure of Vue Server Side Rendering

I didn’t use Nuxt.js but used a boilerplate and implemented it with slight improvements. At first I regretted “should’ve just used Nuxt…” but thanks to that I think it was a good opportunity to learn more deeply about Universal SSR’s execution process. (wrapping grunt work like this)

In this post I want to describe in detail down to the function level about the initialization process of the SSR application I wrote. First, the application’s rendering process is as follows. I’ll describe each process in detail afterward.

- Client requests resources from server

- nginx serves requests to port where Express is running

- Express routing starts

server-entry.jsexecutes- Server’s

vue-routerrouting proceeds - Render HTML using vue-server-renderer

- Server responds to client

client-entry.jsexecutes- Client application initialization function executes

- Client’s

vue-routerrouting proceeds app.$mount

Excluding request #1 and response #7, steps 2-6 are processes happening on the server and steps 8-10 are processes happening on the client. What’s peculiar is that server and client have different entry points.

And as I’ll explain later, these entry points share and use several same functions. Functions like router.onReady or createApp are like that. Originally Universal SSR is basically the concept of “let’s server-side render just the first request and afterward operate like an SPA. And let’s make code reusable on server and client.” So there are convenient aspects, but since execution timing or environment can be completely different even for the same function, there were many confusing parts like needing to do separate exception handling.

And when these two entry points execute on server and client, they go through different initialization processes. If you initialize on the server then initialize everything from scratch again on the client, it’s inefficient, so it uses several methods to perform rendering as efficiently as possible.

Let’s first look at server-side rendering.

Server Side Rendering

Client Requests Resources from Server

The client sends a request to the server.

nginx Serves Requests to Port Where Express Is Running

Usually when developing servers using nodeJS, directly launching servers with commands like node server.js is rare. Usually you use server engines like Nginx or Apache together.

The reasons are as follows:

- Due to server engine software characteristics, faster static file serving than nodeJS is possible. And since such requests aren’t sent to nodeJS but processed at the engine level, backend load is distributed.

- Node.js creator Ryan Dahl once said “You just may be hacked when some yet-unknown buffer overflow is discovered. Not that that couldn’t happen behind nginx, but somehow having a proxy in front makes me happy.” In other words, it means you can prevent attacks from yet-undiscovered vulnerabilities to some extent.

So I wrote roughly the following nginx config:

server {

listen 80;

server_name example.com;

location / {

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header Host $http_host;

proxy_set_header X-NginX-Proxy true;

proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:3000/;

proxy_redirect off;

}

gzip on;

gzip_comp_level 2;

gzip_proxied any;

gzip_min_length 1000;

gzip_disable "MSIE [1-6]\."

gzip_types text/plain text/css application/json application/x-javascript text/xml application/xml application/xml+rss text/javascript;

}When requests come to port 80, they’re forwarded to port 3000 where the nodeJS server executed with node server.js is waiting.

And actually when executing the nodeJS server, it’s better to use a process manager like pm2 or forever to execute it. I’ll write this content in the next post someday. By the way, I’m currently using pm2.

Express Routing Starts

Requests entering like this are processed in the nodeJS server server.js. There’s no Vue code in server.js, only code of the Express framework written in nodeJS.

const fs = require('fs');

const express = require('express');

const createRenderer = (bundle, template) => {

return require('vue-server-renderer').createBundleRenderer(bundle, {

template,

runInNewContext: 'once',

});

};

const bundle = require('./dist/vue-ssr-bundle.json');

const template = fs.readFileSync(resolve('./dist/index.html'), 'utf-8');

const renderer = createRenderer(bundle, template);

const app = express();

app.set('views', './src/express/views');

app.set('view engine', 'ejs');

app.get('/ping', (req, res) => {

debug(`health check from ELB`);

res.render('healthCheck');

});

const bundle = require('./dist/vue-ssr-bundle.json');

const template = fs.readFileSync(resolve('./dist/index.html'), 'utf-8');

const renderer = createRenderer(bundle, template);

app.get('*', (req, res) => {

if (!renderer) {

return res.end('<pre>Rendering bboombboom</pre>');

}

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/html');

const context = { url: req.url, cookie: req.cookies };

if (!context.url) {

errorLog('[ERR] context url is not exist!!', context);

}

// Proceed with render stream

const stream = renderer.renderToStream(context);

});Since I used Express, I naturally used Express’s router. But since Vue proceeds with actual routing, in Express you use wildcards like app.get('*') to execute callback functions for all requests.

Looking in the middle, there’s also code like app.get('/ping') - that’s a router written separately because of AWS Elastic Beanstalk’s Health Check. ELB periodically pings specific URLs of instances belonging to that environment to check if the current environment is operating properly. This URL can be changed in ELB settings, and I set it as the URL /ping.

The reason for separating this router separately is because the more vue-ssr-renderer’s render function executes, the more HTML templates go up in memory, and thereby bottlenecks occur in the render process, so I set it to send a simple page as a response with just Express without executing vue-ssr-renderer.

Express routing and vue-router routing I’ll explain below can be confusing. As I just explained, actual routing proceeds in Vue, but Express receives and processes requests first then passes them to Vue, so routing must be done in Express too. After routing, when the renderToStream method on the last line executes, routing and rendering proceeding in Vue start.

Now I’ll explain the inside of the app.get('*') router in detail.

app.get('*', (req, res) => {

if (!renderer) {

return res.end('<pre>Rendering bboombboom</pre>');

}

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/html');

const context = { url: req.url, cookie: req.cookies };

if (!context.url) {

errorLog('[ERR] context url is not exist!!', context);

}

const stream = renderer.renderToStream(context);

stream.on('data', () => {

/* @desc

* Using vue-meta plugin, you can receive values returned by metaInfo method declared in components.

* Refer to https://github.com/declandewet/vue-meta

*/

const {

title, link, style, script, noscript, meta,

} = context.meta.inject();

context.head = `

${title.text()}

${meta.text()}

${link.text()}

${style.text()}

${script.text()}

${noscript.text()}

`;

})

.on('error', err => {

debug(`Error occurred during rendering`);

// Error handling logic like showing error page is located here.

})

.on('end', () => {

debug(`Rendering ended`);

})

.pipe(res);

});The most important part in this routing is the role of the renderToStream method.

vue-ssr-renderer has 2 render functions: renderToString and renderToStream.

renderToString returns rendered HTML in string form when all rendering finishes, then afterward returns HTML to the client at once. Therefore, if render speed takes long, users have no choice but to look at a blank screen. Also, since it sends data at once, it has the disadvantage of having to put all content in memory when proceeding with HTML rendering. If HTML size is small it’s not a problem, but the larger the file size, the more memory space each rendering eats up.

renderToStream returns a nodeJS ReadableStream object whenever one event finishes. stream is a nodeJS feature that can load data in certain chunk units and manage streams with event callback calls using the on method. The data event is called whenever each chunk becomes readable state, and if all data is loaded, the end event is called. I’ll explain this stream content in another post someday.

server-entry.js Executes

When the renderToStream function executes, vue-server-renderer finds the server-side entry file server-entry.js. In this file, it creates an app object using the factory function in app.js, goes through several initialization processes, then routes.

import { createApp } from './app'; // import factory function

export default context => {

return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => {

// If resolved in this promise, stream continues even after router.push is called

// If rejected in this promise, stream's error event is called.

});

};To explain this file’s code, it’s good to know what app, store, router returned by the createApp function imported at the top are, so before looking closely, let’s first look at the createApp factory function imported at the very top.

The createApp function is a factory function that returns a Vue instance, VueRouter instance, and Vuex’s Store instance. Afterward this factory function is also reused in client-entry to proceed with initialization.

import Vue from 'vue';

import App from './App.vue';

import Store from './stores';

import { Router } from './router';

export function createApp() {

const store = Store();

const router = Router();

const app = new Vue({ router, store, render: h => h(App) });

return {

app, router, store,

}

}It’s similar to code that generally initializes Vue on clients, but there’s one different part - it creates Store and Router instances using factory functions. Usually in SPA applications

export default new Vue({

el: '#app',

components: { App },

template: '<App/>',

router: new VueRouter({ ... }),

store: new Vuex.Store({ ... }),

});You create Vue instances like this. But there’s one problem using this logic as is on the server.

The problem occurs when returning data types using Call by Reference evaluation strategy with export default. Since Vue called in new Vue() operates like a class returning instances, this code ultimately returns the memory address where the Vue instance went up. This logic has no particular problems on clients, but problems can occur on servers.

Unlike clients, servers are programs that, once up, keep running for a long time. Since users currently accessing the server shouldn’t share Store state, servers must create new Store and Vue instances for each request.

But what’s exported in the above code is ultimately the Vue instance’s memory pointer, and when this module is imported, this module creates a Vue instance just once at first, then afterward returns the memory pointer to reference - that is, the same instance.

Therefore, during server-side rendering, to avoid state pollution, you must write it by exposing factory functions instead of instance memory pointers and creating and returning new instances every time.

I missed this fact and created a bug where users shared sessions inside Store, so logging in with my account logged in as someone else’s account. It’s a dizzying moment even thinking about it now.

A Node.js server is a long-running process. When our code is required into the process, it will be evaluated once and stays in memory. … So, instead of directly creating an app instance, we should expose a factory function that can be repeatedly executed to create fresh app instances for each request.

Vue SSR Guide Avoid Stateful Singletons

Even written blatantly like this in the official documentation, I missed it and created a huge bug. We must read official documentation! Read it twice, three times!

Okay, now that we’ve looked at createApp, let’s return to server-entry.js and continue explaining that file.

import { createApp } from './app'; // import factory function

import { TOKEN_KEY } from 'src/constants';

import { SET_TOKEN, DESTROY_TOKEN } from 'src/stores/auth/config';

import APIAuth from 'src/api/auth';

export default context => {

return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => {

const { router, store } = createApp(); // create new app

const cookies = context.cookie;

const authToken = cookies[TOKEN_KEY]; // token in cookie of client that sent request

const next = () => {

router.push(context.url);

};

if (authToken) {

try {

await APIAuth.isValidToken(authToken); // 200 if valid, 400 if invalid

store.dispatch(SET_TOKEN, authToken);

}

catch (e) {

console.error(e); // throwing considers render failed. But render itself shouldn't fail just because token is invalid.

store.dispatch(DESTROY_TOKEN);

}

}

router.onReady(() => {

// Routing logic is located here

}, reject);

next();

});

};This file’s main logic is broadly divided into 2 things:

- If token is stored in cookie of client that sent request, store authentication state in Store with

store.dispatch(SET_TOKEN, authToken) - Server-side routing logic and exception handling declared with

router.onReady

Let’s first look at #1. Why must we necessarily store authenticated tokens in Store? First, since this server is a render server that only performs rendering, session validity checks must communicate with external API servers to perform.

Authentication state may be needed on the server and may also be needed on the client. Then you must communicate once on the server to check tokens and also communicate on the client to check tokens. But since this method is inefficient, frameworks supporting universal SSR like this usually use the method of serializing server state into the window object and declaring it inside <script> tags during rendering to return server state to clients.

In vue-server-renderer, server state to return to clients is declared using Vuex, Vue’s Flux architecture library.

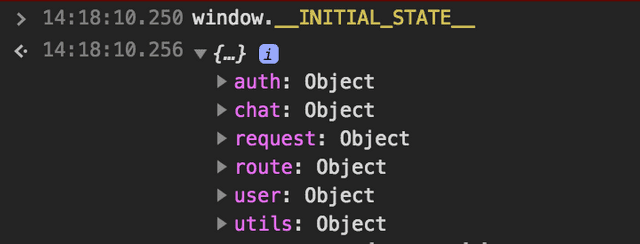

Thus server state gets serialized using JSON.stringify during rendering and contained in the property window.__INITIAL_STATE__, and afterward during client initialization, it accesses that property, uses JSON.parse to convert to Object type, then uses Vuex Store’s replaceState method to update Store.

You can check it like this in browser console

You can check it like this in browser console

Server’s vue-router Routing Proceeds

Let’s look at routing logic that was #2. Universal SSR applications proceed with routing on the server side the very first time users open pages, and afterward when users move pages, routing proceeds on the client.

In other words, routing logic inside server-entry.js is logic that executes exactly once when users initially execute the application for the very first time. Since I wrote router authentication-related logic on the client, only checking whether components are connected to this router on the server, I wrote server-side entry routing logic simply.

The router object used in this file is an instance of the VueRouter class in the vue-router library created and returned by the createApp factory function. I decided to just check whether the current route is a valid route using this class’s getMatchedComponents method.

The meaning of VueRouter’s member variables and methods is also in vue-router’s official documentation, but sometimes libraries are updated but official documentation updates are late, so I directly looked at vue-router’s code.

Looking at the node_modules/vue-router/types/router.d.ts file, you can confirm the VueRouter class’s member variables and methods.

declare class VueRouter {

constructor (options?: RouterOptions);

app: Vue;

mode: RouterMode;

currentRoute: Route;

beforeEach (guard: NavigationGuard): Function;

beforeResolve (guard: NavigationGuard): Function;

afterEach (hook: (to: Route, from: Route) => any): Function;

push (location: RawLocation, onComplete?: Function, onAbort?: Function): void;

replace (location: RawLocation, onComplete?: Function, onAbort?: Function): void;

go (n: number): void;

back (): void;

forward (): void;

getMatchedComponents (to?: RawLocation | Route): Component[];

onReady (cb: Function, errorCb?: Function): void;

onError (cb: Function): void;

addRoutes (routes: RouteConfig[]): void;

resolve (to: RawLocation, current?: Route, append?: boolean): {

location: Location;

route: Route;

href: string;

// backwards compat

normalizedTo: Location;

resolved: Route;

};

static install: PluginFunction<never>;

}You can confirm that the getMatchedComponent method is a method that receives RawLocation type or Route type as arguments and returns a Component list. Then let’s check how getMatchedComponent is implemented in the node_modules/vue-router/dist/vue-router.common.js file.

VueRouter.prototype.getMatchedComponents = function getMatchedComponents (to) {

var route = to

? to.matched

? to

: this.resolve(to).route

: this.currentRoute;

if (!route) {

return []

}

return [].concat.apply([], route.matched.map(function (m) {

return Object.keys(m.components).map(function (key) {

return m.components[key]

})

}))

};The VueRouter class’s getMatchedComponent method returns components matched with that route if it receives a to argument, and if no argument is given, returns components matched with the current route. As confirmed in the VueRouter class’s type declaration, ? meaning optional is attached to the to argument, so unless needed, you don’t need to pass an argument. Now let’s write inside the router.onReady event hook.

router.onReady(() => {

/**

* @desc If there are no components connected to current router, by rejecting

* nodeJS stream's error event is called and separately written errorHandler will render 404 page.

*/

const matchedComponents = router.getMatchedComponents();

if (!matchedComponents.length) {

return reject({

code: 404,

msg: `${router.currentRoute.fullPath} is not found`,

});

}

else {

resolve(app);

}

}, reject);Seems roughly done. But my application is written to wait for asynchronous logic before proceeding with routing using a property called asyncData. I think Vue’s SSR library Nuxt also used a similar method, but I don’t quite remember this part.

Anyway, if there’s a component having asyncData among the component list matched with the current route, it’s simple logic of making it wait using Promise, so I wrote it as follows using Promise.all:

router.onReady(() => {

/**

* @desc If there are no components connected to current router, render 404 page.

*/

const matchedComponents = router.getMatchedComponents();

if (!matchedComponents.length) {

return reject({

code: 404,

msg: `${router.currentRoute.fullPath} is not found`,

});

}

// start: added part

Promise.all(matchedComponents.map(Component => {

if (Component.asyncData) {

return Component.asyncData({ route: router.currentRoute, store, });

}

})).then(() => {

/** @desc

* Pass state to context and use `template` option in renderer, and it serializes context.state and injects into HTML as `window.__INITIAL_STATE__`.

*/

context.state = store.state;

resolve(app);

}).catch(reject);

// end: added part

}, reject);And when all routing completes, if you contain store state in context.state like context.state = store.state, vue-server-renderer automatically injects state into window.__INITIAL_STATE__.

Render HTML Using vue-server-renderer

stream

.on('error', err => {

return errorHandler(req, res, err, bugsnag);

})

.on('end', () => {

debug(`render stream end ==============================`);

debug(`${Date.now() - s}ms`);

debug('================================================');

})

.pipe(res);Thus when Promise.resolve is called in server-entry.js and initialization finishes, the stream’s end event declared earlier in server.js executes, then the chained pipe method executes.

Server Responds to Client

After going through the above process, transmits HTML that finished rendering to the client.

Client Rendering

client-entry.js Executes

After the client receives server-rendered HTML and entry.js, client rendering starts. At this time, the file Webpack catches as the client-side entry point when compiling is client-entry.js. First let’s look at the init function in the client-entry.js file.

Client Application Initialization Function Executes

import { createApp } from './app';

import { LOGIN } from 'src/stores/auth/config';

const { app, router, store } = createApp();

const init = async function () {

/** @desc Synchronize server store with client store */

if (window.__INITIAL_STATE__) {

store.replaceState(window.__INITIAL_STATE__);

}

/** @desc Check token existence then process login */

const hasToken = store.state.auth.authToken;

if (hasToken) {

try {

await store.dispatch(LOGIN);

}

catch (e) {

// Separate exception handling like deleting token in cookie

}

}

return Promise.resolve();

};Since it’s current workplace code, I couldn’t write everything, but the logic the init function performs is reflecting server store state to client and user authentication processing. Since the principle of receiving server store state was explained in server-entry.js execution, this time I’ll try explaining “why process login on client instead of server.”

The reason is because this server is a render server without separate authentication logic, so tasks like getting user information or checking authentication depend entirely on external API servers. Initially I overlooked this fact and chose the method of communicating with APIs during server rendering then sending user data down to clients, but the following problems occurred:

- API communication time was included in HTML template render time. (Since server rendering’s lifecycle also ends when rendering finishes, you have no choice but to synchronously process API communication using the

awaitkeyword during rendering. Even the authenticated user information GET API is quite slow) vue-ssr-renderer’srendermethod’s execution time increased.- As

rendermethod’s execution time increased, more templates went up in memory at once. - Memory fills up and can no longer perform rendering.

- Server cannot respond.

- Fail

So the part I focused on most when building this render server was shortening the render method’s execution time, and as a result, logic fetching user data went down to the client. Thinking about it later, views needing currently authenticated user data are parts not needing SEO, so there was no need to do it on the server. Now let’s finally look at client routing.

Client’s vue-router Routing Proceeds

In client-entry.js, the client-side global router is also declared together.

import { createApp } from './app';

import { LOGIN } from 'src/stores/auth/config';

const { app, router, store } = createApp();

const init = async function () {...};

router.onReady(async () => {

await init();

router.beforeEach((to, from, next) => {

const matched = router.getMatchedComponents(to);

const prevMatched = router.getMatchedComponents(from);

let diffed = false;

const activated = matched.filter((c, i) => {

return diffed || (diffed = (prevMatched[i] !== c));

});

if (!activated.length) {

next();

}

Promise.all(activated.map(c => {

if (c.asyncData) {

return c.asyncData({ store, route: to });

}

})).then(() => {

/* LOADING INDICATOR */

next();

}).catch(next);

});

app.$mount('#app');

});Actually the router part isn’t much different from the routing logic part in sever-entry.js. But one difference is that client-entry.js’s routing has logic comparing the current router’s components with the previous router’s components.

Unlike server rendering where routing happens just once during the first request, client routing happens multiple times according to user actions. Client rendering only newly renders parts where components changed when the router changes and keeps the rest as is, so the next router may be using components that were in the current router as is.

The important point is that on the client too, asyncData is being used to fetch data before routing completes, just like on the server.

In other words, if a component existing in the current router also exists in the next router, there’s no need to perform duplicate logic in that component’s asyncData, so logic must be written to perform logic comparing components when the router changes, then only perform asyncData of changed components.

app.$mount -> Rendering Ends. Vue Lifecycle Starts

Afterward, finally directly mounting the app to #app DOM starts the client-side Vue lifecycle. Lastly I’ll attach the Github link of this project boilerplate.

That’s all for this Vue SSR post.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

What is Universal Server Side Rendering?

Programming/Web/TutorialFixing Webpack Watch Memory Leak

Programming/WebAn Ordinary Developer's Journey to Authorship

EssayImplementing PWA in One Day

Programming/Web/TutorialHow Does the V8 Engine Execute My Code?

Programming/JavaScript