[Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 1. What is Gravity?

How Does Gravity Bend Space?

![[Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 1. What is Gravity? [Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 1. What is Gravity?](/static/6c72a52042fa8bad71e5e927ca2d86d6/2d839/thumbnail.jpg)

In this post, I’m going to implement gravity using the law of universal gravitation. Not gravity acting in one direction on the ground surface, but I plan to make a simulation where I scatter multiple objects with random masses at random coordinates and observe how they interfere with each other’s motion.

What is Gravity?

First, since this post is aimed at people like me who are not familiar with mathematics rather than physics majors, I want to properly establish the concept of gravity before moving on.

Newton said that gravity is the force by which two objects with mass attract each other.

In fact, while Newton figured out how gravity works by creating the formula for the law of universal gravitation, he didn’t know why gravity occurs. He probably passed it off as “only God would know…” And Newton said that objects with mass have gravity, which means that light has no mass and is therefore not affected by gravity at all.

However, according to facts revealed in modern times, light is also affected by gravity. Didn’t we see this in the movie Interstellar? (While it may not be a 100% accurate visual depiction, theoretical physicist Kip Thorne calculated general relativity and visualized it in 3D.)

In places with tremendous gravity like black holes, this phenomenon is noticeably observed, and this is called gravitational lensing.

Bending of light passing behind a black hole

Gravity came to be defined in Einstein’s general relativity in 1915 as the bending of spacetime by energy. So when the mass of an object in spacetime rapidly increases or decreases, waves are created in spacetime, and this is gravitational waves, which were discovered early last year.

Gravitational waves generated like this are said to move at the same speed as light. So if the sun suddenly disappeared from the solar system with a poof!, the planets orbiting around the sun wouldn’t immediately escape their orbits and fly away.

For example, in Earth’s case, since light from the sun takes about 8 minutes and 20 seconds to reach Earth, even if the sun suddenly disappeared, for about 8 minutes we would continue orbiting the position where the vanished sun was. Then 8 minutes later, the moment the last light that left the sun reaches Earth, Earth would break orbit.

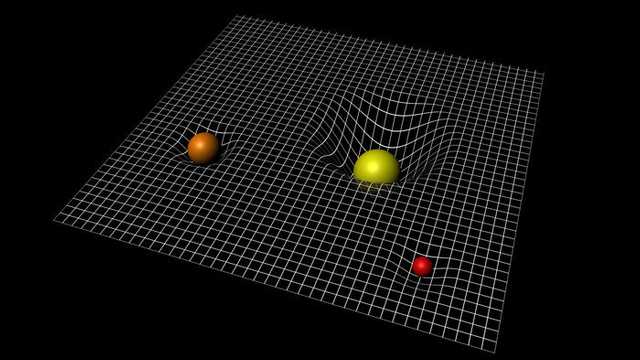

Objects with larger mass bend spacetime more

Objects with larger mass bend spacetime more

This doesn’t mean the law of universal gravitation was wrong; rather, the theory of relativity is closer to complementing what the law of universal gravitation missed. In fact, if it’s not a space with very large gravity (a very bent space), the law of universal gravitation can explain it sufficiently.

For example, Earth is a large sphere overall, but when we who live on Earth look around, we can’t tell whether it’s a sphere or a plane. Similarly, a space where the degree of bending is so small that it’s almost similar to Euclidean space is called pseudo-Euclidean space. And in such pseudo-Euclidean space, applying only the law of universal gravitation is sufficient. They say that even when sending the Apollo spacecraft to the moon, the law of universal gravitation alone was enough.

In conclusion, finding gravity can be seen as finding the curvature of spacetime, but the simple simulation I’m trying to make is simulating situations within a very small pseudo-Euclidean space, and since it’s not a program applied to reality but literally a simulation, it can be sufficiently implemented with just the law of universal gravitation.

So How to Implement?

First, to explain easily, let’s assume we scatter 2 objects with random masses at random coordinates with random directions and speeds into space. Calculating the gravitational influence of these 2 objects is not very difficult. This is where the law of universal gravitation appears.

This formula calculates the gravitational force that object 1 exerts on object 2. Here means the gravitational constant, and this gravitational constant is fixed at 6.67384 * 10^-11.

And and in the numerator are the masses of each object, and in the denominator means the Euclidean distance between these objects. And the multiplied at the end means the unit vector from object 1 looking toward object 2.

The point of this formula is that the distance between objects is in the denominator and the masses of the two objects are in the numerator.

This means that as the distance between two objects increases, the denominator gets larger so the result value becomes smaller, and as the masses of the two objects increase, the numerator gets larger so the result value becomes larger. Simply put, gravity is inversely proportional to the distance between two objects and directly proportional to the product of the masses of the two objects.

For those who haven’t studied linear algebra, simply understanding that a vector means a direction in space should be sufficient. Since the space we’re trying to calculate is 3-dimensional space, vectors have 3 coordinate values: (x, y, z).

The law of universal gravitation we learned when we were young has the form:

The result of this formula has scalar values like 1, 5.2, or 1204. Since scalars only represent physical quantities, you can know how strong gravity is but can’t know the direction of gravity.

So we need to express the direction of force to properly use this formula, which is why we multiply by a vector at the end.

And the reason -1 is attached at the very front of the formula is because of the vector’s direction. The vector we multiplied at the end is the direction from object 1 toward object 2. But gravity is a force that pulls toward me, not a pushing force, so the direction of force should be from object 2 toward object 1. That’s why we multiply by -1 again in the above formula.

It looks a bit complicated, but when actually implemented in code, it’s simple. I proceeded with vector calculations using ThreeJS.

import { Vector3 } from 'three';

function calcGravity(o1, o2, G) {

// Find the difference between o1's position vector and o2's position vector to get the vector looking from o1 -> o2.

let force = new Vector3().subVectors(o1.location, o2.location);

// Find the length of the direction vector obtained above and convert to absolute value.

const distance = Math.sqrt(force.length() ** 2);

// Convert the direction vector obtained above to a unit vector.

force = force.normalize();

// Get gravity scalar

const strength = -(G * o1.mass * o2.mass) / (distance ** 2);

// Multiply the direction vector by the gravity scalar obtained above

force = force.multiplyScalar(strength);

return force;

}Now if we keep adding the value from here to the position value of the current object being calculated, the object will move in that direction. But the problem is that in reality we’re not just going to scatter 2 objects.

That law of universal gravitation is considering and calculating only the gravity between 2 objects. Then can we also calculate multiple objects’ gravity influencing and receiving influence from each other?

Unfortunately, such n-body problems are one of the most difficult problems in mathematical physics, and in 1887, Henri Poincaré said it was impossible to find a general solution to three-body or greater problems. So we have no choice but to approximately calculate gravity using the two-body problem’s law of universal gravitation above.

In the next post, I plan to implement a simple gravity model sample in code. That’s all for the first post on implementing gravity with JavaScript.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

[Implementing Gravity with JavaScript] 2. Coding

Programming/Graphics[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Implementing Planetary Motion

Programming/Graphics[Simulating Celestial Bodies with JavaScript] Understanding the Keplerian Elements

Programming/GraphicsIs the Randomness Your Computer Creates Actually Random?

Programming/Algorithm[Deep Learning Series] Understanding Backpropagation

Programming/Machine Learning