Beyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

Understanding Applicative Functors and Monads through TypeScript

In this post, I’ll continue from the concept of functors I covered previously and move on to explaining monads.

When people hear “monad,” the first thing that usually comes to mind is the infamous explanation: “A monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors, blah blah blah.” While this is technically the most accurate description of a monad, it’s also the most unhelpful one.

There’s even a well-known meme called the “monad curse” — the idea that the moment you understand monads, you lose the ability to explain them. For those of us who aren’t deeply versed in mathematics, monads are indeed a notoriously elusive concept.

With that in mind, I’m going to take my own ambitious crack at explaining monads. (Of course, I might fail…)

What We Covered in the Previous Post

Since the previous post was written a full six years ago, let me briefly recap its content before moving on. For the full details, refer to the previous post.

Despite all the complexity and lengthy explanations, the core idea is simple. In the world of functional programming, to compose functions, the output type of the first function must match the input type of the next function.

The problem is that the programming world is full of uncertainties and side effects — null, undefined, errors, and so on — making it difficult to follow this rule.

function getFirstLetter(s: string): string | undefined {

return s[0];

}

function getStringLength(s: string): number {

return s.length;

}

// Since getFirstLetter's codomain is string | undefined,

// it can't be directly composed with getStringLength

getStringLength(getFirstLetter(''));To solve this problem, we introduced the concept of wrapping values and side effects in a container, and that container was the functor.

A functor is a structure that can safely transform the value inside a container without extracting it, through an operation called map.

map: F<A> → (A → B) → F<B>This type signature means that if you pass a computation (A → B) that transforms the internal value to the map operation of a functor F<A>, the result is F<B> — the internal value has been transformed.

Here, even though the internal value of F<A> and F<B> may differ, the structure itself must not change, which is why a functor must satisfy the following two laws:

- Identity law:

- Composition law:

is the identity function that returns its argument unchanged. The identity law says that applying map with this identity function should result in nothing happening.

The composition law means that mapping a composed function should produce the same result as mapping each function separately and then composing.

These laws exist because they guarantee that a functor is “a mapping that preserves structure.” It’s not mathematical obsession — there are real practical reasons.

If the identity law holds, we can trust that a.map(x => x) truly does nothing. But if the internal structure — like the order of a list or the height of a tree — were altered in the process, that’s no longer mapping; it’s “reconstruction.” The identity law is what lets you trust that a functor only touches the contents, never the wrapper.

And if the composition law holds, we’re guaranteed that a.map(f).map(g) produces the same result as a.map(x => g(f(x))).

This guarantees that a.map(f).map(g), which loops twice, can be collapsed into a.map(x => g(f(x))) with a single loop and produce the same behavior. Conversely, it also means it’s safe to split complex logic into multiple map calls for readability.

But even functors have their limits. It’s precisely these limitations that lead us to the monad we’ll explore today.

The Limits of Functors

In 1988, computer scientist Eugenio Moggi at the University of Edinburgh was wrestling with a thorny problem. While working on denotational semantics — the study of defining the meaning of programs mathematically — he was pondering how to bridge the gap between pure lambda calculus and real-world programs.

In pure lambda calculus, the type means “a total function that takes input A and returns B.” Mathematically clean, but real programs don’t work that way.

Programs can fall into infinite loops, throw exceptions, modify state, or read files. Treating programs that produce these “effects” as pure functions distorts their meaning.

So Moggi’s starting point was to view programs not as but as . Here, is a structure that captures the “notion of computation,” and means “a computation that produces a value of type B.” It represents not the value itself, but a computation that produces the value, as a type.

This is easier to understand with concrete examples. Familiar computations include:

- : a computation that might fail

- : a computation that interacts with the outside world

- : a computation that modifies state

But this approach introduced another problem: composing functions of the form became tricky. If the first function is , then the second would be , but the output of the first function, , doesn’t match the input of the second, .

Moggi discovered that a structure solving this composition problem had already been studied in category theory — and that’s how monads entered functional programming.

The word “monad,” borrowed from mathematics, became one of the most feared words in computer science.

Why Can’t Functors Solve This?

So why couldn’t Moggi’s problem be solved with functors alone? We encounter two critical bottlenecks that the functor’s map cannot resolve.

First, consider the case where a function gets trapped inside the computational context . A typical example that produces this situation is currying.

const maybeA: Maybe<number>;

const maybeB: Maybe<number>;

const add = (a: number) => (b: number) => a + b;const map: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Maybe<B>;Can we use the functor’s map to apply the add operation to maybeA and produce a function waiting for the next argument? The answer is no. Because the result of applying the operation through the functor’s map isn’t just a plain function.

const addA = map(maybeA, add);// Substituting into map's type signature...

map<number, (b: number) => number>(

maybeNumber: Maybe<A>,

add: (a: number) => (b: number) => number

): Maybe<(b: number) => number>Normally, with a curried function, addA should have the type (b: number) => number. But here, since we applied the operation through map, the result is Maybe<(b: number) => number>. The function is trapped inside the computational context.

The problem is that once this happens, we can’t continue composing with the functor’s map, which only accepts bare functions. map can apply a function from outside the context to a value inside the context, but it has no way to take a function trapped inside a context and apply it to a value inside another context.

This is fundamentally because the functor’s map only operates on the outermost function when given a curried function. When a function returns another function, map can’t reach the inner one.

The other problem arises when composing two functions that each return a functor. Let’s look at another example using the Maybe functor, which represents “a value that may or may not exist.”

const findUser: (id: number): Maybe<User>;

const findTeam: (user: User): Maybe<Team>;These are functions of the form Moggi envisioned — taking an input and returning a computation .

findUser takes a user ID and returns a User. We use the Maybe functor because if an invalid ID is provided, there may be no matching user. And findTeam takes a User and returns their team. We want to compose these two functions to create a function that finds a user’s team.

The problem is that findTeam can’t directly accept the Maybe<User> returned by findUser.

But we can try composing them using the functor’s map. Let’s give it a shot.

map(findUser(1), findTeam);

// Substituting into map's type signature...

map<User, Maybe<Team>>(maybe: Maybe<User>, f: (a: User) => Maybe<Team>): Maybe<Maybe<Team>>We managed to compose them, but the resulting type is Maybe<Maybe<Team>> — a rather sad outcome. If we were to add one more step to find the team leader from the team information, the type would become Maybe<Maybe<Maybe<Manager>>>, nesting infinitely.

Let’s Take Stock

Following Moggi’s problem, we’ve encountered two issues that functors can’t solve.

| Problem | Cause | What’s Needed |

|---|---|---|

| Applying a function inside a context | map only accepts functions from outside |

An operation that applies an inner function to an inner value |

| Context nesting | map only peels one layer |

An operation that flattens double context into single context |

I thought functors could solve everything, but that turned out to be far from true

I thought functors could solve everything, but that turned out to be far from true

Problems are meant to be solved. Now we’re going to sketch out the design for these, step by step.

The first problem — a function trapped inside a context — can be solved by an Applicative Functor. And the problem of contexts nesting every time we compose functions — that’s what the Monad solves.

Designing the Solution: Applicative Functors and Monads

Now we need to invent a new operation to solve the first problem. From here on, the phrase “computational context” is too long, so let’s simply call it a “container.”

The first problem was a function being trapped inside a container, so we need an operation that can apply this function to a value inside another container.

// Apply a function inside a container to a value inside another container

apply: T<(A → B)> → T<A> → T<B>The only difference between this operation and the functor’s map is whether the function being applied is outside or inside the container. We call this operation apply.

We also need an operation that puts a value back into a container after applying the function. This is called the pure operation.

// Put a pure value into a container

pure: A → T<A>A functor equipped with both apply and pure is called an Applicative Functor. Let’s express these operations as TypeScript type signatures using the familiar Maybe container as an example.

const apply: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: Maybe<(a: A) => B>): Maybe<B>

const pure: <A>(value: A) => Maybe<A>Now let’s use this applicative functor to compose the curried function from our earlier problem.

const maybeA: Maybe<number>;

const maybeB: Maybe<number>;

const add = (a: number) => (b: number) => a + b;const maybeAddA = map(maybeA, add); // Maybe<(b: number) => number>;

apply(maybeB, maybeAddA); // Maybe<number>// Substituting into apply's type signature...

apply<number, number>(

maybe: Maybe<number>,

f: Maybe<(b: number) => number>

): Maybe<number>With the applicative functor’s apply operation, the problem of working with multiple containers like maybeA and maybeB just… solves itself.

The Limits of Applicative Functors

But the problem we solved comes with an important premise: which containers to compose must be known in advance.

Think back to the applicative functor’s apply operation. maybeA and maybeB are independent containers that are already in our hands before computation begins. In other words, the structure of the computation is fixed regardless of the values.

But real-world programs are far more dynamic. More often than not, you need to look at the result of the previous computation before deciding which container to fetch next — or whether to fetch one at all.

// Find a user, then find their team based on user information.

// The team-finding function produces different results depending on who the user is.

findUser(1).fn(user => findTeam(user.teamId))Here’s where another problem arises. The Maybe container returned by findTeam is created depending on the value user. In other words, the result of the previous computation determines the context of the next.

Applicative functors can only facilitate communication between containers that already exist, so they can’t express sequential dependencies that are dynamically created at runtime.

| Static | Dynamic |

|---|---|

| “Fetch A and B separately and combine them” | “Fetch A, then decide whether to do B based on the result” |

To handle dynamically created sequential dependencies, you have to use the result of the previous computation to create the next one. And in that process, containers will inevitably nest.

Oh, what if we had an operation that flattens nested containers?

Oh, what if we had an operation that flattens nested containers?

Applicative functors used a new operation called apply to execute functions inside containers. But if we had a tool that flattens nesting, we wouldn’t need the cumbersome step of executing a function inside a new container — we could solve the problem without it.

const maybeA: Maybe<number>;

const maybeB: Maybe<number>;

const add = (a: number) => (b: number) => a + b;// If we have something that flattens nesting, we can solve it with just map!

// 1. Mapping a curried function produces a function inside a container

const maybePartialFn = map(maybeA, add);

// Result: Maybe<(b: number) => number>

// 2. Use map to access the function inside the container and perform computation

const nested = map(maybePartialFn, fn => map(maybeB, fn));

// Result: Maybe<Maybe<number>>

// 3. Then flatten the nesting?

const result = flattener(nested);

// Result: Maybe<number>Just compose and let things nest, then flatten afterward.

Monads: Inventing the Flatten Operation

And that’s exactly what monads are for. A monad is something that has an operation for flattening nested containers.

This flattening operation is called join or flatten.

join: T<T<A>> → T<A>const join: <A>(maybe: Maybe<Maybe<A>>) => Maybe<A>The join operation turns Maybe<Maybe<A>> into Maybe<A>. Mathematically, it “reduces two applications of down to one.”

This kind of operation is actually easy to find in our daily work — JavaScript’s Array.prototype.flat does exactly this.

And just like the applicative functor, we also need an operation that puts a pure value into a container. As with applicative functors, this is called pure, or sometimes of.

pure: A → T<A>const pure: <A>(value: A) => Maybe<A>But in practice, you rarely use join directly. As we saw in the earlier example, the monad works as a set: use map to access something inside the container and compose, then use join to flatten the nesting.

1. You want to apply a function to the value inside a container = use map

2. But that function returns its result wrapped in a container = double wrapping occurs

3. You need to unwrap the double wrapping = use joinSo we want to combine these two operations into one for convenience.

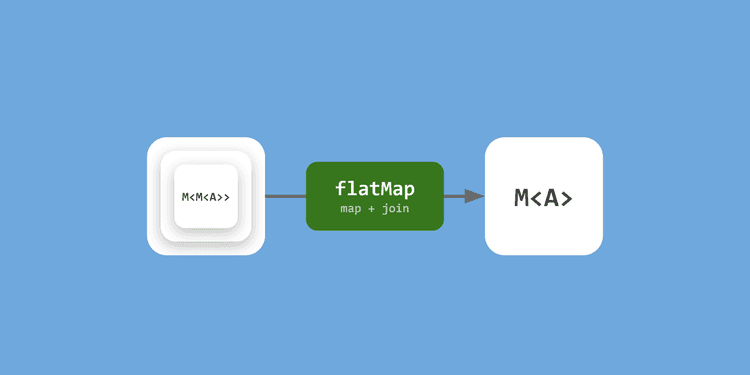

flatMap = map + join

Since calling map followed by join every time is tedious, we combine these two steps into flatMap. Let’s see what the type signature looks like for a flatMap that takes our familiar Maybe container.

map: T<A> → (A → B) → T<B> // Apply a regular function

flatMap: T<A> → (A → T<B>) → T<B> // Apply a container-returning function + flattenconst map: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Maybe<B>;

const flatMap: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => Maybe<B>): Maybe<B>The difference between map and flatMap is in the second argument. map takes a simple A => B function, while flatMap takes an (A => Maybe<B>) function.

Although it’s not visible in the type signature, flatMap internally performs the role of join as well, so the result type isn’t the sad Maybe<Maybe<B>> but simply Maybe<B>.

Now we can use flatMap to express sequential dependencies between computations.

// Using map results in a nested type

findUser(1).map(user => findDepartment(user.deptId));

// Maybe<Maybe<Department>>

// Using flatMap solves it

findUser(1).flatMap(user => findDepartment(user.deptId));

// Maybe<Department>So far, we’ve covered the functor’s map, the applicative functor’s apply, and the monad’s flatMap. There was a lot of ground to cover, so let’s recap before moving on.

// Functor's map

const map: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Maybe<B>;

// Applicative Functor's apply

const apply: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: Maybe<(a: A) => B>): Maybe<B>

// Monad's flatMap

const flatMap: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => Maybe<B>): Maybe<B>First, map is the one that applies a regular function to a value inside a container. But this alone can’t handle functions trapped inside the container.

So apply appeared. apply makes it possible to access functions inside a container, enabling composition even in these situations. But when performing dynamic computations with sequential dependencies, containers kept nesting.

To solve this, join — which flattens nested structures — was combined with the functor’s map to create flatMap. Through this operation, we can now freely compose computations with sequential dependencies, where each result determines the next computation.

Laws Are Proofs About Refactoring

So is flatMap really the magic that lets us safely compose functions? Well, to claim this with confidence, flatMap must satisfy a few laws.

The Three Laws

To use flatMap freely, we need the guarantee that this operation upholds the following laws.

Associativity: It Shouldn’t Matter Which Layer You Flatten First

First is the associativity law. It means that when flattening nesting, the result should be the same regardless of which side you flatten first. Imagine a container wrapped in three layers, like Maybe<Maybe<Maybe<A>>>.

We need to flatten this container down to the form.

There are two ways to flatten this to a single layer. The first is to merge the inner two s first, then peel off the remaining outer to get . The second is to merge the outer two s first, then peel off the remaining inner .

Regardless of which order you perform the operations, the final result must be the same. That’s the associativity law.

m.flatMap(f).flatMap(g) === m.flatMap(x => f(x).flatMap(g))In the formula above, (mu) represents join.

Here, means “merge the inner two layers,” and means “merge the outer two layers.” Think of it like a three-layered matryoshka doll being reduced to two layers — it shouldn’t matter whether you merge the inner dolls first or the outer dolls first.

Left Identity: Don’t Mess with the Entry Point

Second is the left identity law. This means that putting something in and immediately taking it out should be the same as doing nothing.

pure(a).flatMap(f) === f(a)In the formula above, (eta) represents pure.

Pay special attention to the in front of () — it means applying pure not outside the container but to a value already inside one.

In other words, given a container , if you wrap the inner value with pure to create a double structure , and then flatten it back with join (), you should arrive back at the original state ().

This law must hold for us to trust pure as the minimal unit of computation inside a container. If the left identity law were broken, it would mean pure is doing more than simply wrapping a value — it would be transforming the internal logic.

Right Identity: If You Only Changed the Wrapping, the Contents Should Stay the Same

Third is the right identity law. It’s similar to the left identity law, but the order of wrapping is reversed.

m.flatMap(pure) === mHere, means treating the existing container as a single value and wrapping its outside with pure () one more time. The result is , creating a double structure .

What the right identity law says is straightforward. If you wrap the outside of a container with one more layer of pure () and then peel that outer layer back off with join (), you should end up right back where you started ().

As mentioned earlier, these identity laws are important because they guarantee that pure is a neutral identity element that doesn’t distort the context.

Just as adding to a number doesn’t change the value, wrapping a container with pure and then flattening it should have no effect whatsoever on the original information or state of that container.

Back to “A Monoid in the Category of Endofunctors”

So how does all this relate to the Wikipedia definition of a monad as “a monoid in the category of endofunctors”?

From here on, the discussion gets more abstract and mathematical, so readers who are satisfied with a practical-level understanding of monads can skip ahead.

But it's great exercise for the brain, so I still recommend reading through it

But it's great exercise for the brain, so I still recommend reading through it

Monads weren’t handed down from mathematicians with the instruction “use this.” Engineers needed a safe way to compose functions, so they invented these tools out of necessity.

| Invention | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A type constructor that takes a type and creates a new type | Maybe<A>, Array<A>, … |

|

| (eta) | An operation that puts a value into a container | pure, Promise.resolve, … |

| (mu) | An operation that flattens nested containers into a single container | join, flatten, … |

And to use these operations safely, we said they must satisfy the three laws we examined (associativity, left identity, right identity). Now, analyzing this structure mathematically leads us to a very interesting destination.

Category: A World of Objects and Arrows

A category is a structure composed of objects and morphisms (arrows) between them. Personally, I find the word “category” more natural than the Korean translation, so I’ll stick with “category” going forward.

From a TypeScript perspective, the most familiar category is the category of types. In this category, the objects are types like number and string, and the morphisms are functions like (a: number) => string — computations that go from one object to another.

For a detailed treatment of categories and functors, see the previous post.

Endofunctor: A Functor That Stays Within the Same World

The “category of endofunctors” in the definition of a monad refers to a category made up of endofunctors.

As I briefly noted in the previous post, a functor is a mapping that takes one category to another. A general functor maps from category to a different category , but an endofunctor maps from — meaning the source and destination are the same category.

Why is a monad an object in the “endofunctor category”? Because the functors we use in programming ultimately stay within the programming world. Consider the functor’s map operation, for example.

const map: <A, B>(maybe: Maybe<A>, f: (a: A) => B): Maybe<B>;Looking at this type signature, map takes A and produces B. The key point is that A is a type in TypeScript’s type system, and the result type Maybe<B> is also a type in TypeScript’s type system.

It goes from the world of types to the world of types. That’s why functors in programming are endofunctors. They don’t go to another world — they transform within the same one.

The Endofunctor Category: A World Where Functors Themselves Are Objects

Now let’s step up one level of abstraction. If we know that functors used in programming are endofunctors, we can conceive of a new category where endofunctors themselves are the objects.

| Regular Type Category | Endofunctor Category | |

|---|---|---|

| Objects | number, string, … |

Maybe, Array, Promise, … |

| Morphisms | (a: A) => B |

Functor → Functor |

Since morphisms in a category go from one object to another, morphisms in the endofunctor category go from one functor to another.

A morphism that transforms one functor into another is called a Natural Transformation.

Monoid Object: The Algebra of Combining

Now that we’ve covered the “category of endofunctors” part of the definition, let’s look at what it means to be a “monoid object.”

In mathematics, a monoid is a structure equipped with the following three things:

- A set or collection of objects

- A binary operation: combines two elements to produce an element within the same set. Must satisfy associativity.

- An identity element: a special element that, when combined with any other element, returns that element unchanged.

The concept is abstract enough to feel intimidating, but the examples aren’t that complicated. The most classic monoid is the relationship between integers and addition.

With integers and addition, the addition operation takes two elements from the set of integers and returns another integer. Just like . And as you already know, addition satisfies the associativity law. Finally, the identity element — the number that returns any integer unchanged when added — is .

This is why the set of integers paired with addition can be called a “monoid,” and mathematically it’s denoted as . (Strictly speaking, integers under addition also have inverses, making it a group, but that’s not important for this explanation.)

The Connection: A Monad Is a Monoid Object in the Category of Endofunctors

Now that we understand what a monoid is, we can finally understand what “a monoid object in the category of endofunctors” means.

The endofunctor category is a category composed of programming functors like Maybe and Promise, so we just need to check whether these objects form a monoid structure.

Let’s compare the relationship between integers and addition — our representative monoid — with the relationship between endofunctors and their composition operation.

| Monoid Element | Integer Addition | Endofunctor Category |

|---|---|---|

| Binary operation | + () |

Composition ∘ () |

| Result of operation | Integer | Endofunctor |

| Identity element | 0 |

Identity functor Id |

The comparison looks roughly similar. But there’s one problem: the result of the endofunctor binary operation isn’t but — a nested result. In other words, it’s not an element within the same set.

This is exactly where the monad’s join () and pure () that we defined earlier come in.

| Operation | Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

join () |

A natural transformation that merges two layers of T into one | |

pure () |

A natural transformation from the identity functor to T |

A natural transformation is a “structure-preserving transformation between functors.” It’s important that pure isn’t simply “putting a value in a container” but a natural transformation. This means pure must behave consistently for any type — it cannot behave differently depending on the type.

And if we revisit the monad laws from earlier, we can see that they satisfy the associativity and identity element laws that a monoid requires.

| Law | Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Associativity | Same result regardless of merge order | |

| Identity law | Wrapping and unwrapping returns the original. i.e., is the identity element. |

The laws we established for programming turn out to be exactly what a monoid requires.

| Monoid of Integers | Monoid in Endofunctor Category (= Monad) | |

|---|---|---|

| Object | Integer | Endofunctor (Maybe, Array, …) |

| Binary operation | join () () |

|

| Identity element | pure () () |

|

| Associativity | ||

| Identity law |

This is why we can call the monads we use in programming “a monoid object in the category of endofunctors.”

But as I mentioned, this definition isn’t why we started using monads in programming. We just needed to compose computations with effects sequentially, invented join and pure to do it, and then noticed that what we’d built happened to match “monoid” — a structure mathematicians had known about for centuries.

Actually, Monads Aren’t Boxes

So far, we’ve used Maybe as a concrete example to dissect how monads work. But in practice, what matters more than just implementing the code is understanding the context these tools carry and recognizing how they differ from existing tools.

Many monad tutorials, including my own earlier ones, have explained functors and monads using the “box” metaphor. While intuitive, this metaphor only tells half the story.

If you think of Promise as merely “a box containing a future value,” it’s hard to explain why then must execute sequentially. So rather than calling functors and monads simple boxes, it’s more accurate to describe them as “the context of a computation accompanied by a particular effect.”

Therefore, what flatMap does isn’t simply “open the box and flatten it” — it’s closer to “safely chaining computations with different contexts.”

| Monad | Context (Effect) |

|---|---|

Maybe |

The context of a value that might not exist |

Result |

The context that includes the reason for failure (error) |

Promise |

The context of an asynchronous computation that takes time |

Array |

A nondeterministic context where multiple results may exist |

One more thing worth noting: we need to reconsider Promise. In code, Promise behaves in a very monadic way, but under strict mathematical scrutiny, it’s not a monad.

A monad requires map (which preserves structure) and flatMap (which flattens structure) to be strictly separated, but Promise’s then mixes them depending on the return value.

On top of that, a mathematical monad must allow a doubly-nested state to exist, but Promise doesn’t allow this at runtime — it collapses immediately into a single layer. Convenient in practice, but it breaks the mathematical properties that make monads predictable.

Therefore, strictly speaking, Promise cannot be called a monad.

Closing Thoughts

With that, we’ve completed the long journey from functors through applicative functors to monads.

Looking back, this whole thing started from a pretty practical question: “How can we compose functions safely?” We met apply to get past the limits of functors, invented join and flatMap to deal with nesting, and then noticed that what we’d built was “a monoid object in the category of endofunctors” — something mathematicians already had a name for.

What’s nice about this is that the monad laws give us real confidence when writing code. The identity laws mean pure won’t mess with your data. The associativity law means you can refactor freely without changing behavior. That kind of trust is what lets you build complex business logic out of small, composable pieces.

Understanding monads is really about learning to handle abstract contexts and getting some mathematical backing for the code you write.

I’ve done my best to take a stab at explaining monads, but honestly, I have no idea whether this article ended up being easy or difficult.

If you have any further questions, feel free to reach out via email and I’ll do my best to explain. I’d love the interest and support of fellow functional programming enthusiasts.

With that, I conclude this post: Beyond Functors, All the Way to Monads.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

How Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/ArchitectureWhy Do Type Systems Behave Like Proofs?

ProgrammingFrom State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingMisconceptions About Declarative Programming

Programming[All About tsconfig] Compiler options / Emit

Programming/Tutorial/JavaScript