Misconceptions About Declarative Programming

It's not syntax — it's a shift in thinking that produces truly declarative code

When conducting technical interviews, I often ask candidates about the reasoning behind their decisions in take-home assignments.

A common answer I hear is “because this approach is more declarative.” But when I follow up with “What makes it declarative?” or “What does declarative code actually mean?”, clear answers are surprisingly rare.

So in this post, I want to share my thoughts on what it truly means for code to be declarative.

Many developers believe they’re writing declarative code, but they often miss the essence, confusing the use of a specific tool or syntax with being declarative.

In my view, declarative programming isn’t about tools. It’s a fundamental shift in how you think.

The most common misconception about declarative programming

The first trap many developers fall into is the belief that “abstracting procedural behavior into functions makes it declarative.” But using functions doesn’t automatically make your code declarative.

Let’s start with a simple example. Here’s a procedural way to fetch user information:

function getUserInfo(userId) {

const connection = connectDB();

const userRow = connection.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?', userId);

const permissionRows = connection.query('SELECT * FROM permissions WHERE user_id = ?', userId);

const user = {

id: userRow.id,

name: userRow.name,

email: userRow.email,

permissions: permissionRows.map(row => row.permission_name)

};

if (user.name) {

user.displayName = user.name.toUpperCase();

}

return user;

}This code uses a function, but it focuses on temporal sequencing: “first fetch the user from the DB, then add permissions, and finally format the data.” Using a function doesn’t free you from procedural thinking.

Declarative code shifts focus away from temporal ordering and toward describing the relationships between operations.

// Declarative approach — focus on data transformation relationships

const getUserInfo = (userId) =>

pipe(

fetchUserFromDB,

addUserPermissions,

formatUserData

)(userId);

// Or more explicitly

const getUserInfo = (userId) =>

formatUserData(

addUserPermissions(

fetchUserFromDB(userId)

)

);This code declares the relationship “user ID → formatted user info.” It focuses on the relationships between data transformations, not on execution order.

The distinction is clear. Procedural code focuses on “How — step by step.” Declarative code focuses on “What — what relationship do we want?”

This misconception is especially common with array methods. Many people assume that using map, filter, or reduce automatically makes code declarative.

But you can absolutely think procedurally while using array methods:

// Array methods used with procedural thinking

function processItems(items) {

return items

.map(item => {

let price = item.basePrice;

if (item.discount) {

price = price * (1 - item.discount);

}

price = price * 1.1;

return { ...item, finalPrice: Math.round(price * 100) / 100 };

})

.filter(item => item.finalPrice > 0);

}A declarative approach, by contrast, focuses exclusively on describing the business relationships each transformation represents:

// Truly declarative approach

const processItems = (items) =>

items

.map(applyDiscount)

.map(addTax)

.map(formatPrice)

.filter(hasValidPrice);

const applyDiscount = (item) => ({

...item,

price: item.basePrice * (1 - (item.discount || 0))

});

const addTax = (item) => ({

...item,

price: item.price * 1.1

});

const formatPrice = (item) => ({

...item,

finalPrice: Math.round(item.price * 100) / 100

});

const hasValidPrice = (item) => item.finalPrice > 0;The first version uses array methods but still focuses on step-by-step processing. The second version clearly declares the business relationship each transformation represents.

What matters is proper abstraction — each function clearly expressing what it does.

Functions are neutral tools. You can wrap procedural thinking in a function, or express relational thinking through one. The essence of declarative programming isn’t whether you use functions — it’s what kind of abstraction those functions provide.

These rough examples might not fully convey the idea, so let’s dig into the fundamentals.

Declarative programming from a mathematical perspective

To properly understand declarative programming, we first need to understand the concept of “declaration” itself. The easiest way is to start with everyday examples.

Think about a cooking recipe. The procedural approach is like a recipe: “Boil 2 cups of water, add the noodles and cook for 3 minutes, add the seasoning and cook for 1 more minute, serve in a bowl.” It’s a set of instructions that follow a timeline.

The declarative approach expresses relationships: “Ramen = cooked noodles + seasoning + hot water.” It describes the essential relationships between ingredients.

A recipe is a set of instructions ordered by time. A relational declaration describes the essential relationships between components. This difference is the fundamental distinction between procedural and declarative thinking.

Let’s look at a clearer example from math. Consider the linear function that we all learned in school. This expression is not a command telling a computer to “multiply by 2 and add 1.” It’s a declaration that “this relationship exists between and .”

This declaration is a timeless truth because it describes a relationship. Whenever is 3, is 7 — always, everywhere. The computation process or execution order doesn’t matter. What matters is the relationship between and itself.

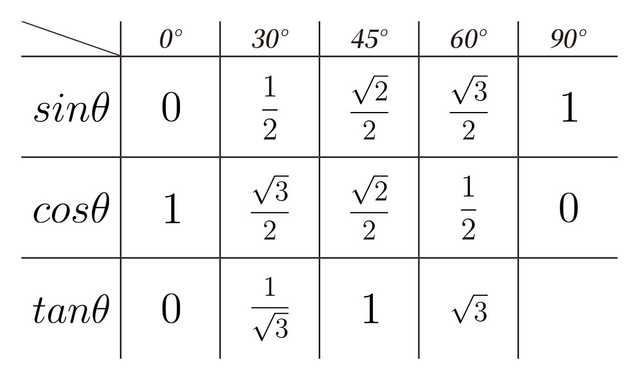

What mathematicians focus on when defining functions is precisely these invariant relationships. A function isn’t a computation algorithm — it’s a correspondence between structures. When we define the trigonometric function , we’re declaring the relationship between an angle and the -coordinate on the unit circle, not prescribing how to calculate it.

Memorizing the trigonometry table means memorizing the relationships that sin, cos, and tan express

Memorizing the trigonometry table means memorizing the relationships that sin, cos, and tan express

The same applies to programming. Declarative code doesn’t order a computer to do something — it expresses “the essence of this problem lies in these relationships.” From this perspective, programming becomes not about dictating computation steps, but about discovering and expressing the mathematical structure of a problem domain.

Procedural vs. declarative: a difference in thinking

Now let’s look at concrete examples that approach the same functionality from both mindsets. Procedural thinking focuses on changes that happen over time: “First do this, then do that…” — a sequential execution model.

// Procedural programming — focused on How

function calculateTotalPrice(items) {

let total = 0;

// Step 1: Iterate through each item

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

const item = items[i];

// Step 2: Validate

if (item.quantity > 0) {

// Step 3: Calculate base price

let itemPrice = item.price * item.quantity;

// Step 4: Apply discount

if (item.discount) {

itemPrice = itemPrice - (itemPrice * item.discount);

}

// Step 5: Accumulate total

total = total + itemPrice;

}

}

return total;

}This code focuses on temporal order and state changes. You have to track what happens at each step and how variables mutate.

Declarative thinking, on the other hand, focuses on timeless logical relationships. It declares: “total price = the sum of discounted prices of valid items.”

// Declarative programming — focused on What

const calculateTotalPrice = (items) =>

items

.filter(hasValidQuantity)

.map(calculateItemPrice)

.reduce(sum, 0);

const hasValidQuantity = (item) => item.quantity > 0;

const calculateItemPrice = (item) =>

item.price * item.quantity * (1 - (item.discount || 0));

const sum = (a, b) => a + b;This code declares data transformation relationships. Each function represents a specific transformation, and their composition solves the whole problem.

In programming, this difference manifests in the kind of abstraction the code expresses. Procedural code abstracts over the computer’s execution process — memory allocation, loop execution, conditional branching — wrapping mechanical operations in variables and control structures. Declarative code abstracts over the logical structure of the problem domain — expressing conceptual relationships like business rules, data relationships, and state transformations through functions and types.

So why does this relational thinking matter? The fundamental reason is human cognitive limitations. According to psychologist George Miller’s research, human short-term memory can only handle about 7±2 units of information simultaneously.

In procedural thinking, you must track all state changes over time, and as programs grow complex, the combinations of states explode exponentially. With 10 variables, there are possible states, and at each step you need to consider all of them. Tracking all these changes is nearly impossible for human memory.

With relational thinking, you manage complexity through composition of invariant relationships. It’s the same principle as expressing a complex function as a composition of simpler ones in math. In , you don’t need to know the internals of both and to understand — you only need to understand each one’s input-output relationship.

This relational thinking lets us chunk complex states into manageable pieces, greatly helping us understand complex code.

Why is JSX declarative?

Let’s now look at JSX, a declarative tool we encounter daily. I want to address the question “Why is specific code declarative?” through the lens of JSX.

One pattern I frequently see in interviews is answering “What is declarative code?” with “It’s using tools like JSX or React.” When I follow up with “So why is JSX declarative?”, the answer is often “Because using JSX lets you write declarative code” — a textbook circular argument.

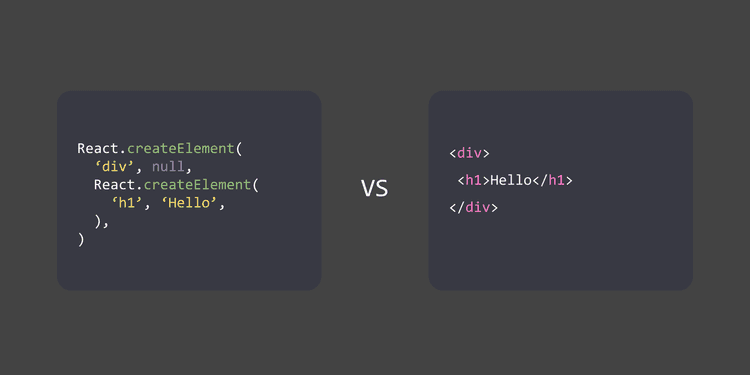

The real reason JSX is declarative lies in how it expresses structural relationships. Let’s compare two approaches:

function createUserProfile(user) {

const container = document.createElement('div');

container.className = 'user-profile';

const nameElement = document.createElement('h2');

nameElement.textContent = user.name;

container.appendChild(nameElement);

const emailElement = document.createElement('p');

emailElement.textContent = user.email;

container.appendChild(emailElement);

if (user.avatar) {

const avatarElement = document.createElement('img');

avatarElement.src = user.avatar;

avatarElement.alt = `${user.name}'s avatar`;

container.appendChild(avatarElement);

}

return container;

}function UserProfile({ user }) {

return (

<div className="user-profile">

<h2>{user.name}</h2>

<p>{user.email}</p>

{user.avatar && (

<img src={user.avatar} alt={`${user.name}'s avatar`} />

)}

</div>

);

}The first version focuses on the order of creating and manipulating DOM elements: “First create a container, then create a name element and append it, then create an email element and append it…” Temporal order matters — changing the order of appendChild calls changes the result.

The JSX version focuses solely on declaring: “A UserProfile is a structure composed of a name, email, and optionally an avatar.” What matters here is the containment and hierarchy between elements — temporal order is irrelevant.

The correspondence between data and UI

JSX’s real power lies in its ability to intuitively express the correspondence between data structures and UI structures.

const TodoList = ({ todos }) => (

<ul>

{todos.map(todo => (

<TodoItem

key={todo.id}

text={todo.text}

completed={todo.completed}

/>

))}

</ul>

);Looking at this code, you can immediately read the relationship: each item in the todos array corresponds to a TodoItem component. The structure of the data becomes the structure of the UI.

The same behavior written imperatively looks like this:

function createTodoList(todos) {

const ul = document.createElement('ul');

for (let i = 0; i < todos.length; i++) {

const li = document.createElement('li');

li.textContent = todos[i].text;

if (todos[i].completed) {

li.classList.add('completed');

}

ul.appendChild(li);

}

return ul;

}In the imperative version, procedural steps — data iteration, element creation, attribute setting, DOM insertion — are all tangled together. To understand the relationship between the data structure and the final UI, you have to read the entire code and mentally execute it.

Expressing structural relationships

JSX is similar to how mathematics expresses set relationships. When we write , we declare that set is composed of elements . This relationship is independent of the order in which elements were added.

JSX works the same way. When we write code like this, we declare “UserCard is composed of Avatar and UserInfo.” This relationship is conceptually separate from the order in which components are rendered.

// Declaration of structural relationships

const UserCard = ({ user }) => (

<div className="user-card">

<Avatar src={user.avatar} />

<UserInfo name={user.name} email={user.email} />

</div>

);It focuses solely on declaring “a user card is a combination of an avatar and user info.” How each component is implemented and in what order they’re added to the DOM are separate concerns.

From this perspective, JSX is declarative not merely because it hides complex processes, but because it lets you directly express the essential relationships between data and UI.

Now that we understand why JSX is declarative, a question might arise:

“But JSX ultimately compiles to

createElement, and React’s reconciliation is procedural code too, right? Is it really declarative then?”

Declarative and procedural are relative

This is a critical point when understanding abstraction and declarative programming — treating these concepts as absolutes leads to serious misconceptions.

In reality, the same code can be declarative or procedural depending on your vantage point and level of abstraction. “Declarative” and “procedural” aren’t absolute categories. They’re relative concepts.

Let’s examine this relativity through a React Query example:

// Application level — declarative

function useUserData(userId) {

return useQuery(['user', userId], () => fetchUser(userId));

}

function UserProfile({ userId }) {

const { data: user, isLoading, error } = useUserData(userId);

if (isLoading) return <div>Loading...</div>;

if (error) return <div>An error occurred</div>;

return <div>{user.name}</div>;

}From the application developer’s perspective, this code is completely declarative. It declares a relationship: “a query that fetches user data for a given userId.” Complex logic like caching, retries, and error handling is all abstracted away.

But the QueryClient implementation code behind useQuery is procedural — cache checks, network requests, state updates, and retry logic are all laid out explicitly.

This relativity becomes especially clear at domain boundaries. Looking at an order processing function at the business logic level:

// Business logic level — declarative

async function processOrder(order) {

const validatedOrder = await validateOrder(order);

const payment = await processPayment(validatedOrder);

const shipment = await scheduleShipment(validatedOrder);

return createOrderConfirmation(validatedOrder, payment, shipment);

}This function is declarative from a business logic perspective — it clearly expresses the relationships: “validate the order, process payment, and schedule shipping.” But the infrastructure-level functions underneath, like payment processing, are procedural:

// Infrastructure level — procedural

async function processPayment(order) {

const paymentGateway = new PaymentGateway(process.env.PAYMENT_API_KEY);

try {

const paymentRequest = {

amount: order.total,

currency: order.currency,

source: order.paymentMethod

};

const response = await paymentGateway.charge(paymentRequest);

if (response.status === 'succeeded') {

await database.payments.create({

orderId: order.id,

paymentId: response.id,

amount: response.amount,

status: 'completed'

});

return { success: true, paymentId: response.id };

} else {

throw new PaymentError(response.error);

}

} catch (error) {

await logger.error('Payment processing failed', { orderId: order.id, error });

throw error;

}

}The concept of “declarative” is relative depending on which layer you’re observing from. The point of declarative code is how well the abstracted parts are expressed so you need to inspect the procedurally written parts less.

Another common prejudice is that “procedural code is bad and should always be avoided.” This too is misguided. Even the most elegant functional code ultimately runs as procedural CPU instructions.

What matters is providing the right abstraction at the right level.

Understanding this relativity reveals that finding appropriate abstractions at each level is what’s important. Not everything needs to be declarative. At the business logic level, a declarative approach works well because the focus should be on expressing the essential relationships of the domain. At the infrastructure level, procedural code is perfectly fine because efficient, safe implementation matters more.

The key is to draw clear boundaries and match the level of abstraction. It must be clear which level handles which concerns. In a good design, the business level declaratively expresses the shopping cart’s structure, while the infrastructure level uses procedural calculation logic — and that’s perfectly fine.

// Good example: Clear level separation

// Business level — declarative

const ShoppingCart = ({ items, onCheckout }) => (

<div className="shopping-cart">

<ItemList items={items} />

<TotalPrice items={items} />

<CheckoutButton onClick={() => onCheckout(items)} />

</div>

);

// Presentation level — declarative

const ItemList = ({ items }) => (

<ul className="item-list">

{items.map(item => (

<ItemCard key={item.id} item={item} />

))}

</ul>

);

// Infrastructure level — procedural is OK

function calculateTotalWithTax(items, taxRate) {

let subtotal = 0;

for (const item of items) {

subtotal += item.price * item.quantity;

}

const tax = subtotal * taxRate;

return subtotal + tax;

}From this perspective, declarative programming isn’t about “making all code declarative” — it’s about “having the right expressiveness at the right level of abstraction.”

Code that looks declarative vs. code that actually is

Now let’s concretely answer the core question: “What makes specific code declarative?” The essence of declarative code is clearly defining the relationships between possible states.

Just as mathematics defines the domain of a function precisely, a program should first declare “which state combinations are logically possible.”

Consider asynchronous data requests. In reality, only states like idle, loading, success (with data), and error (with an error message) are logically possible. A state that is “loading while simultaneously having data and an error” is a contradictory combination that can’t happen in reality.

Let’s examine this through handling async data in a React + TypeScript environment.

Code that looks declarative — focused on state change processes

An async data hook written with a procedural approach focuses on how state changes:

// Procedural approach — focused on how state changes

function useAsyncData<T>(fetcher: () => Promise<T>) {

const [data, setData] = useState<T | null>(null);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(false);

const [error, setError] = useState<string | null>(null);

useEffect(() => {

// Step 1: Transition to loading state

setLoading(true);

setError(null);

setData(null);

fetcher()

.then(result => {

// Step 2: Transition to success state

setData(result);

setLoading(false);

})

.catch(err => {

// Step 3: Transition to error state

setError(err.message);

setLoading(false);

setData(null);

});

}, [fetcher]);

return { data, loading, error };

}Truly declarative code — focused on state relationships

The declarative approach focuses on what the possible states are:

// Declarative approach — focused on what states are possible

type AsyncDataState<T> =

| { status: 'idle' }

| { status: 'loading' }

| { status: 'success'; data: T }

| { status: 'error'; error: string };

function useAsyncData<T>(fetcher: () => Promise<T>): AsyncDataState<T> {

const [state, setState] = useState<AsyncDataState<T>>({ status: 'idle' });

useEffect(() => {

setState({ status: 'loading' });

fetcher()

.then(data => setState({ status: 'success', data }))

.catch(error => setState({ status: 'error', error: error.message }));

}, [fetcher]);

return state;

}Why is the first version procedural?

The first version focuses on the sequence and process of state changes: “First set loading to true, reset error to null, reset data to null…” — a series of procedural commands.

The more critical problem is that impossible state combinations are permitted at the type level. TypeScript can’t prevent a nonsensical state like { data: someUserData, loading: true, error: "Network Error" }. Having data while simultaneously loading and having an error is a logical contradiction. But with the first approach, the developer must manually guarantee the validity of all state combinations.

You have to check at every setState call whether the other states are properly reset — and this easily leads to human error. For instance, forgetting setLoading(false) on success, or omitting setData(null) on error.

Why is the second version declarative?

The second version declares the essential state relationships of the “async data request” domain. Through a union type, it expresses the invariant relationship “exactly one of these four states can exist” at the type level.

The key point is that impossible states are blocked at the source. The TypeScript compiler prevents contradictory combinations like “loading and success at the same time” at compile time. This follows the same principle as clearly defining a function’s domain in mathematics. In , is the domain of function , and is undefined for values outside .

Let’s look more concretely at the safety guarantees union types provide:

// Safety enforced by TypeScript at compile time

function handleAsyncState<T>(state: AsyncDataState<T>) {

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle':

return "Not started yet";

case 'loading':

return "Loading...";

// Accessing state.data or state.error here causes a compile error

case 'success':

return `Data: ${state.data}`;

// state.data is guaranteed to exist here

// Accessing state.error causes a compile error

case 'error':

return `Error: ${state.error}`;

// state.error is guaranteed to exist here

// Accessing state.data causes a compile error

default:

// TypeScript verifies all cases are handled

const exhaustiveCheck: never = state;

return exhaustiveCheck;

}

}In each case, only the properties valid for that state are accessible — attempting to access other properties results in a compile error. The never type in the default case lets the compiler verify that all cases have been covered.

Differences in component usage

Using the first approach requires the developer to manually handle all combinations:

// First approach — manual handling of all combinations

function DataDisplay<T>({ fetcher, render }: {

fetcher: () => Promise<T>;

render: (data: T) => React.ReactNode;

}) {

const { data, loading, error } = useAsyncData(fetcher);

// Developer must manually consider every combination

if (loading && !error && !data) return <LoadingSpinner />;

if (error && !loading) return <ErrorMessage error={error} />;

if (data && !loading && !error) return render(data);

// How do we handle unexpected state combinations?

// What about { loading: true, data: someData, error: null }?

return <div>Unknown state</div>;

}The second approach lets the types guarantee complete coverage:

// Second approach — types guarantee all cases

function DataDisplay<T>({ fetcher, render }: {

fetcher: () => Promise<T>;

render: (data: T) => React.ReactNode;

}) {

const state = useAsyncData(fetcher);

// TypeScript verifies all cases are handled

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle':

return <div>Ready...</div>;

case 'loading':

return <LoadingSpinner />;

case 'success':

// state.data is guaranteed to be of type T

return render(state.data);

case 'error':

// state.error is guaranteed to exist

return <ErrorMessage error={state.error} />;

// TypeScript verifies at compile time that all cases are covered

// Adding a new state triggers a compile error for unhandled cases

}

}TypeScript verifies that all cases are handled and guarantees that the relevant properties exist in each case. When a new state is added, compile errors surface any missed spots.

Differences in extensibility

Consider a scenario where you need to add new states. With the first approach, you must modify multiple variables:

// First approach — must modify multiple variables

const [retrying, setRetrying] = useState(false);

const [stale, setStale] = useState(false);

// Each state change requires considering combinations with all other states

// Of 16 boolean combinations, how many are logically valid?With the second approach, you simply extend the type definition:

// Second approach — just extend the type definition

type AsyncDataState<T> =

| { status: 'idle' }

| { status: 'loading' }

| { status: 'retrying'; previousError: string; attempt: number }

| { status: 'success'; data: T; stale?: boolean }

| { status: 'error'; error: string };

// TypeScript forces handling of new cases at all usage sites

// Compile errors surface any missed spotsAdding a new state makes TypeScript enforce handling at every usage site. Compile errors reliably surface anything you’ve missed, allowing safe extension.

The essence of declarative thinking in this example is defining “what is possible” first. Just as mathematics defines a function’s domain and range precisely, we explicitly declare the possible states of an async request.

Procedural approaches focus on “how to change state,” while declarative approaches first declare “which states are logically possible in this problem domain.” This shift in perspective is the essence of declarative programming.

Practical guidelines

Now let’s distill the theory into concrete criteria for real-world application. Here are practical guidelines for when to choose procedural vs. declarative approaches.

When should you take a declarative approach?

Business logic and state management benefit from a declarative approach. As with the async data state example above, when complex state combinations are possible, it’s important to block impossible states at the type level:

// Reusing the AsyncDataState example from above

type AsyncDataState<T> =

| { status: 'idle' }

| { status: 'loading' }

| { status: 'success'; data: T }

| { status: 'error'; error: string };UI structure is also a natural fit for the declarative approach. As we saw with JSX, you can directly express the structural relationship between data and UI:

// Reusing the JSX example — clearly declaring structural relationships

const UserProfile = ({ user }) => (

<div className="user-profile">

<h2>{user.name}</h2>

<p>{user.email}</p>

{user.avatar && <img src={user.avatar} alt={`${user.name}'s avatar`} />}

</div>

);Data transformation pipelines also benefit from a declarative approach when each step can be independently defined and tested:

// Clearly declaring transformation relationships

const processUserData = (rawUsers: RawUser[]) =>

rawUsers

.filter(isActiveUser)

.map(normalizeUserData)

.map(addComputedFields)

.sort(byLastLoginDate);When is a procedural approach acceptable?

Infrastructure-level code and performance optimization are well suited to procedural approaches.

As discussed in the relativity section, when efficiency and performance matter, procedural implementation is natural:

// Reusing the calculation logic example from above

function calculateTotalWithTax(items, taxRate) {

let subtotal = 0;

for (const item of items) {

subtotal += item.price * item.quantity;

}

const tax = subtotal * taxRate;

return subtotal + tax;

}Complex state management and optimization in library code, like React Query’s internals, also calls for procedural approaches. Cache checks, network requests, state updates, and retry logic are more efficiently implemented procedurally.

System-level code with complex error handling is another good fit:

// Complex error handling and retry logic

async function retryWithBackoff<T>(

operation: () => Promise<T>,

maxAttempts: number = 3

): Promise<T> {

let lastError: Error;

for (let attempt = 1; attempt <= maxAttempts; attempt++) {

try {

return await operation();

} catch (error) {

lastError = error as Error;

if (attempt === maxAttempts) {

throw lastError;

}

const delay = Math.pow(2, attempt - 1) * 1000;

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, delay));

}

}

throw lastError!;

}Closing thoughts

Declarative programming isn’t about using specific syntax or tools. It’s a shift in thinking, from “how” to “what,” from procedures to relationships.

The core ideas: relational thinking over temporal sequences. Declaring possible states upfront and blocking impossible ones at the type level. Providing the right abstraction at the right level. And remembering that “declarative” is always relative to the layer you’re looking at.

Declarative programming is a way of thinking, not a tool. When you internalize that, the code you write starts to look different.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

From State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingFunctional Thinking – Breaking Free from Old Mental Models

Programming/ArchitectureBeyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingHow Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/ArchitectureHow to Keep State from Changing – Immutability

Programming/Architecture