What Do People Work For? – The Psychology of Motivation

A leader's job isn't to lead: it's to make people move

In this post, I want to briefly share what I’ve been thinking about over the past three years, not as an IC (Individual Contributor) but as a leader, about what makes a good leader and what competencies that requires.

No matter how good someone was as an IC, that experience doesn’t automatically translate into leadership capability. That realization is what naturally led me down this path of inquiry.

What many developers find difficult when they take on a leader or manager role stems from the fact that, unlike computers, humans don’t behave logically at all.

When you give a computer the command A, it understands A and executes A. Humans almost never interpret A as straightforwardly as that. Every person carries biases shaped by the environment they grew up in and the experiences they’ve accumulated, so even when you say the same thing, each person may react differently.

Computers are also guaranteed to deliver the same performance under the same conditions. Humans, on the other hand, might deliver 100% performance one day and suddenly drop to 50% for entirely illogical reasons — making their behavior hard to predict.

People who were recognized for their ability to work with computers — those perfectly logical machines — are suddenly asked to deal with humans, who are anything but logical. It would be stranger if they didn’t find it difficult.

I, too, have experienced various types of failure — demoralizing team members through poor decisions, or failing to provide psychological support when it was needed — largely because I lacked a fundamental understanding of human nature.

That’s why I came to believe that a leader needs more than just communication skills. You need a humanities-grounded understanding of yourself, of human psychology and instinct, and of organizational dynamics. To become a good leader, I thought I first needed to deepen my understanding of human nature and the characteristics that emerge when these “human objects” form a group.

What makes a good leader?

When I first took on the F-Lead role at Toss three years ago, and later the Frontend Chapter Lead role at Quotalab, the first question I asked myself was: “What is a good leader?”

Since “good” is a subjective value judgment that inevitably differs from person to person, there’s no definitive right answer. But I believed that without my own philosophy and definition, I’d lose direction and end up being a leader who stands for nothing.

A leader’s role is to get diverse people within an organization moving in a particular direction, in step with each other. The word “lead” implies pulling from the front, so you might think that’s what good leadership looks like. But I believe that as long as you can get people moving in the right direction, it doesn’t much matter whether you’re pulling from the front or pushing from behind.

What makes people move?

If a leader’s role isn’t simply to control people but to get them moving in a particular direction, then the next question is: what is the force that makes people move?

Fortunately, fields like psychology and education have already spent a long time discussing and experimenting with the principles of human motivation and behavior. I was able to approach the problem step by step by reading research papers and experimental findings.

Self-determination theory

The theory that caught my attention was Self-Determination Theory, one of the major theories of motivation. It states that humans are beings who motivate themselves through internal factors like interest and curiosity, actively developing their sense of self toward psychological growth and integration. The theory identifies three key needs, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, that show a strong positive correlation with intrinsic motivation.

Similar to Andragogy, which is often discussed in the context of lifelong learning, understanding what drives adult behavior places particular emphasis on autonomy — the learner’s own will.

Since autonomy is ultimately a psychological product of feeling that you’re acting by your own choice, I believe that to guide people’s behavior in a particular direction, you first need their empathy toward that direction.

Empathy, after all, isn’t something that can be force-fed from the outside (short of brainwashing). It’s an emotion that must be self-determined and self-convinced, which makes it the most suitable emotion for triggering intrinsic motivation.

However, if you try to drive people’s behavior through external control factors alone — without any intrinsic motivation in place — their resistance to stress will be low when obstacles arise.

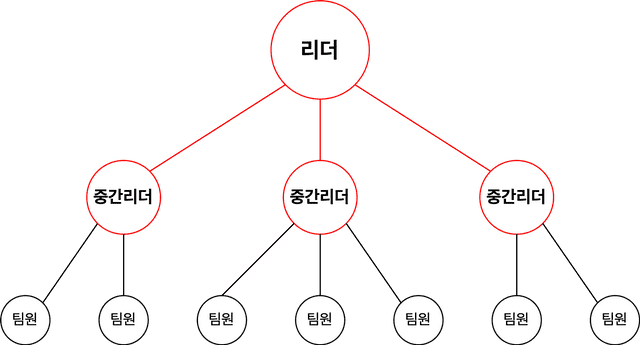

Some argue that leadership through persuasion and empathy doesn't scale with larger teams,

Some argue that leadership through persuasion and empathy doesn't scale with larger teams,but organizations that large typically don't have the leader directly communicating with every member anyway.

The leader communicates this way to middle leaders, who in turn do the same with their teams.

This is especially critical in environments like startups, where people often have to endure high workloads and long hours to achieve distant missions. Stress undermines productivity, engagement, and sense of belonging — it’s not something you can dismiss as just an individual’s problem.

In other words, no matter how passionately a leader talks about their goals, team members without intrinsic motivation won’t simply fall in line and give their all. Even if they go along, their behavior is fundamentally driven by external control factors — the leader’s goals and authority — so expecting that behavior to persist under severe stress is unrealistic.

External motivation also tends to focus on results rather than the act itself, giving it an instrumental quality. Some research suggests that if controlling stimuli are applied — like saying “You’re doing well following my instructions” — it can undermine autonomy and intrinsic motivation, significantly reducing productivity.

This is particularly true for people in industries like IT that require creativity rather than mechanical repetition. There’s also the view that extrinsic motivators like monetary incentives are even less effective for such workers. Moreover, continuously providing extrinsic motivation risks damaging intrinsic motivation in the long run, so very careful reward design is needed. (Imagine a company that provides performance-linked bonuses and then suddenly stops. Wouldn’t people start thinking “Why bother if there’s no money in it?“)

That’s why I concluded that to keep team members highly motivated and actively contributing even in stressful environments, you need to build an environment where they feel maximum autonomy, ensuring a strong tendency toward self-actualization among the people in the organization.

Making people feel they decided for themselves

From a leader’s perspective, it’s certainly easier to use external control factors (rewarding high performers, punishing underperformers, or leveraging organizational politics) to get people moving.

But as I mentioned, intrinsic motivation matters a lot in driving adult behavior. Relying solely on external control factors creates an environment ripe for side effects like low morale, gossip, or people checking out entirely.

Unlike material resources, human resources are entities capable of emotion and thought, making them difficult to predict and control through a mechanistic lens.

So leaders need to create an environment where intrinsic motivation can emerge. There are many methods: appropriate delegation of decision-making authority, environments where people can taste small wins (technical and business), clear goals and expectations. But among these, I placed the most weight on the value of autonomy.

The autonomy a team member feels at work comes from things like exercising decision-making authority over their product, a leader who asks for opinions rather than issuing directives, and being given choices and allowed to make their own selections. It’s about the team member feeling — or actually experiencing — that they’re contributing to the organization through their own autonomous agency.

Since autonomy isn’t a clear-cut sensation like pain but rather a psychological awareness of exercising one’s own agency, even if team members are unknowingly moving in the direction the organization wants, as long as they believe they have autonomy, that autonomy is effectively secured.

There’s also substantial empirical research — both domestic and international — showing that work autonomy has a significant positive correlation with organizational trust, job satisfaction, engagement, and performance. In other words, the fact that autonomy can trigger intrinsic motivation appears to hold regardless of commonly cited East-West differences in thinking.

Of course, given the nature of a company, you can’t guarantee 100% autonomy for everyone. But as I mentioned, autonomy is a psychological awareness rather than an objective sensation — so even just showing that the leader supports team members’ autonomy can have an effect. Alternatively, depending on the leader’s skill, it may be possible to help internalize and integrate externally assigned motivations.

Actions leaders can take to strengthen team autonomy

So what specific methods can strengthen team members’ autonomy?

I believe the first step is to analyze and diagnose the current state of the organization — specifically, what motivates each person. Since autonomy is a precondition for creating intrinsic motivation to boost productivity and engagement, if people already have intrinsic motivation, there’s not much to worry about. (Though in practice, when you actually observe and analyze, surprisingly few people operate on intrinsic motivation.)

You could ask directly in 1-on-1 meetings — “Do you find your current work enjoyable?” or “Why did you become a developer?” — but personally, I prefer analyzing information that comes up in casual conversation.

The reason is that the moment you ask someone a question, they might develop biased thinking around that question. Combined with the inherent discomfort of meeting with a leader and the collectivist tendency of not wanting to stand out, they may not share their true feelings. Asking questions without biasing the other person is critically important in situations like user research and interviews — and it’s harder than you’d think.

That’s why I believe the information that emerges in relaxed settings — smoking a cigarette together, chatting at a café, grabbing dinner after work — tends to be more honest and valuable than what comes out in official 1-on-1 meetings.

The more comfortable the environment and the more friendly gestures you show, the more likely people are to be honest with you.

The more comfortable the environment and the more friendly gestures you show, the more likely people are to be honest with you.

I’d record pieces of information I deemed meaningful, and then categorize people’s motivations using the classification method proposed in an academic paper on applying Self-Determination Theory to HRD:

| Motivation Type | Behavioral Principle | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Amotivation | Don’t know why I’m doing this | I don’t know why I have to do this work |

| External Regulation | To obtain a result | I do this work to score well on performance reviews |

| Introjected Regulation | Out of obligation | I do this because I should be a good team member |

| Identified Regulation | Because it’s important | I do this because it’s necessary for the company’s growth |

| Integrated Regulation | Because it represents my values | I do this because it expresses who I am |

| Intrinsic Motivation | Because the work itself is interesting | I do this because the work itself is fascinating and fun |

🤔 One interesting observation: people who were earlier in their careers more often had introjected regulation or intrinsic motivation, while those with more experience more often showed external regulation or identified regulation.

Perhaps those who chose development because “coding is fun” still carry that initial learning motivation, while more senior developers have accumulated responsibilities beyond personal interest.

In any case, the leader’s role as I defined it is to move people operating on extrinsic motivations — external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, integrated regulation — toward operating on intrinsic motivation. Simply put, it means figuring out what makes “an environment where people enjoy working” and striving to create it.

And the way to internalize motivation is to make team members feel autonomy. Given that a leader’s role inherently involves conveying messages on behalf of the organization, leaders easily become the source of extrinsic motivation — which is why I had to consciously take actions that strengthened team members’ autonomy.

Here are the main methods I used:

- Avoid top-down, notification-style decision-making

- Delegate final decision-making authority to each squad’s frontend engineers for their own services

- Always discuss the frontend chapter’s reason for existence, goals, and mission together

- Communicate that a leader is not a boss, and that mutual feedback is essential

Avoid top-down decision-making

The most fundamental stance I took as a leader was avoiding notification-style decisions. Notification is essentially external pressure that expects compliance, and it severely undermines team members’ autonomy.

So when making decisions about the chapter, I made a point of sharing problems and directions openly — posting agenda items in Slack channels, walking over to ask people directly, adding items to weekly meeting agendas — ensuring everyone in the chapter had an opportunity to participate in the decision-making process.

Not everyone's opinion can be reflected in every decision,

Not everyone's opinion can be reflected in every decision,but at least opening the opportunity to participate provides a degree of autonomy.

It’s true that having the leader make decisions first and then announce them for feedback is faster. But I believed that preserving team members’ intrinsic motivation mattered more than the speed gained from top-down announcements. That’s why I chose to collect feedback before making decisions. Besides, in a small organization of just 5–6 people like the one I led, the leader actively gathering opinions doesn’t significantly slow things down. (And no matter how talented the leader, it’s hard to beat collective intelligence.)

I also judged that if people are given the chance to participate in decision-making, they’re more likely to empathize with the final decision compared to a simple announcement. Even if their opinion wasn’t adopted, they had the chance to voice it and hear the reasoning behind why it wasn’t — a form of equality of opportunity.

Of course, depending on the team member’s personality and situation, some may find it hard to voice their opinions. But since the organization provided ample opportunity to speak up, whether or not they actually do so is their own choice, which doesn’t significantly violate their autonomy.

However, the leader’s response should differ depending on whether someone’s reluctance stems from an internal characteristic like an introverted personality, or from external factors like being new to the company, having recently been criticized, or having been burned by office politics at a previous job.

This is a common preconception among workers in Korean corporate culture,

This is a common preconception among workers in Korean corporate culture,so don't expect people to speak up enthusiastically just because you ask for opinions.

In the former case, if someone’s personality simply doesn’t incline them toward asserting their views, pushing them to share opinions probably won’t change anything. You can change simple behaviors like habits, but altering the personality of someone already in adulthood is no easy feat. (This is why hiring well from the start is so important.)

In this case, the person may be in a state of amotivation or may not have clearly established their growth direction, so you need to find some motivating factor through conversation and at least provide extrinsic motivation. In the latter case, simply removing the blocking factor or showing supportive gestures can naturally increase their participation.

Of course, given the nature of a company, there are decisions made by executives or decisions that can’t be openly discussed — situations where notification becomes unavoidable.

In those cases, explain in detail to the team: why the notification is happening, who the decision-maker is, and the reasoning behind the decision. Express that you’re sorry it had to be communicated this way.

If you don’t properly explain the rationale behind such notifications, team members will feel disrespected by the organization, which can damage intrinsic motivation. The leader must make clear that this isn’t about disrespecting the team, and thoroughly explain the circumstances that made it unavoidable.

Delegate final decision-making authority to each squad’s frontend engineers

The second value I upheld was ensuring that each squad’s frontend engineers had final decision-making authority over their own services.

Even as chapter lead, I couldn’t make product decisions on their behalf. If I had a good idea, I’d propose it to the relevant squad’s engineer and delegate the choice to them. Many organizations withhold decision-making authority from juniors or new hires, but I delegated trust and authority regardless of experience level.

I had two main reasons for this. First, to create intrinsic motivation through autonomy, as discussed above. Second, to ensure that the emotions around success and failure from decision outcomes were felt most strongly by the team member themselves.

I believe all humans grow through failure, so each individual’s sense and emotional response to failure within the team is extremely important.

But if a leader gives specific instructions, the emotions around success and failure no longer belong to the team member. The leader held the final decision-making authority, and the team member merely followed orders — so the emotional weight of outcomes tends to be attributed to the decision-maker, the leader. (If the leader also has a self-serving bias (taking credit for successes and blaming others or circumstances for failures), team members’ frustration will only grow. In the worst case, the team implodes.)

When a team member makes their own decision and faces the consequences, the sense of responsibility they feel is far greater than when the leader made the call for them. I believe this is the most fundamental element of what people commonly call the “autonomy and responsibility” principle.

However, if you design this environment and then blame team members for their failures, that’s a shortcut to disaster. This kind of environment must be accompanied by a value like this:

Everyone can fail. It’s okay to fail.

But if you do fail, make sure you extract the lessons learned and share them so your colleagues don’t repeat the same mistakes.

New hires and junior members especially tend to fear failure, so the leader absolutely needs to say this explicitly. You could also intentionally show small failures of your own as the leader, though this approach can backfire and erode trust if you haven’t built enough rapport yet — so read the room.

These kinds of practices aren’t common in typical Korean companies, so some team members may be experiencing them for the first time. In such cases, side effects can occur — people being afraid of being the decision-maker, or beating themselves up for not expressing their thoughts well — requiring appropriate responses from the leader.

From the leader’s perspective, when you delegate final decision-making authority, you’re still on the hook if things go wrong. Delegating authority doesn’t free you from responsibility for the team’s failures. In other words, by delegating final decision-making to team members, you deliberately create a situation where you have responsibility without authority. (You have to dig your own grave.)

Some leaders might feel anxious about losing control when they delegate decision-making authority. But if you’ve built sufficient rapport or present solid logical reasoning, most team members will seriously consider the leader’s proposals before making their decision — and in the end, things often go the way the leader suggested anyway.

What matters, then, is the leader’s persuasive ability and the trust they’ve built with team members. If a team member doesn’t follow my suggestion, I think it’s healthier to reflect on whether I failed to persuade them, rather than to blame them.

Over a year and a half, I delegated final decision-making authority to various frontend engineers. Regardless of experience level, anyone who passed the three-month probation could participate as an interviewer, among other policies. Apart from occasional cases where someone was nervous about having decision-making responsibility, it was rarely a problem. In most cases, through chapter-wide discussions or suggestions from me or other colleagues, people made good decisions.

For interview process participation in particular, there were reactions like “Am I really qualified to evaluate someone?” But starting with résumé screening, they quickly adapted — and some even ended up proposing improvements to fill gaps in the interview process.

If anything, this decision-making structure enabled the frontend chapter to make decisions quickly, which translated to increased overall performance.

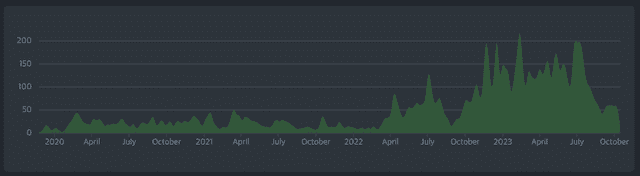

You can roughly gauge performance by looking at the trend of commits merged to main.

You can roughly gauge performance by looking at the trend of commits merged to main.I joined in March 2022, and the frontend chapter only grew by three people over that period.

While some expressed concern about this system, the reality is that I only delegated final decision-making — I didn’t tell anyone to be a dictator. Any team member’s decision-making process was naturally accompanied by suggestions and feedback from other team members. The pressure of being responsible for their own decisions also compelled them to strive for the most rational choices possible.

This feedback came in various forms — code reviews, Slack discussions, or offline conversations — and the decision-maker would hear diverse opinions from colleagues before making the final call. Most problems get caught through this process.

There may be small failures early on when you first delegate, but as I discussed, since the failure resulted from their own choice, they’ll naturally work to avoid repeating the same mistakes. The motivation for this effort might be extrinsic — not wanting to lose colleagues’ trust, or self-satisfaction — but humans inherently possess a need for competence, a desire to be recognized by others. Nobody wants to look incompetent, so they inevitably make the effort.

Of course, if someone keeps repeating the same failures, you need to provide appropriate feedback while being careful not to let them lose too much sense of competence through self-deprecation like “I’m hopeless at everything.” Just be honest — acknowledge what they’re doing well and suggest working together on areas that need improvement. (I found myself saying this kind of thing a lot when helping colleagues strategize for passing their probation period.)

By delegating decision-making authority to the engineer who knows their squad’s situation best and supporting them, you remove the funnel of reporting to and getting approval from someone — increasing decision speed. You accelerate growth by letting team members directly experience the emotions of failure. And in the long run, you strengthen team members’ autonomy and competence.

However, this kind of decision-making structure carries a high risk of devolving into everyone-does-their-own-thing chaos, so clear goal alignment across the entire team is absolutely essential.

Always discuss the chapter’s reason for existence and mission together

The third value I upheld was always discussing the frontend chapter’s reason for existence and mission together as a team. An organization, by definition, is a group formed to achieve goals that can’t be accomplished alone — its very raison d’être comes from its mission.

If people have no say in something this important, it’s only natural for their sense of belonging to decline. So when defining the frontend chapter’s purpose, I made every effort to incorporate as many team members’ opinions as possible.

These missions were typically defined in OKR format, and I made sure discussions focused more on the Objective — the essence of the mission — than on Key Results, which are merely indicators of whether the mission has been achieved.

A clear goal like “we are a team organized to achieve X, our mission is Y, and our strategy to achieve it is Z” is essentially a belief about why the frontend chapter can meaningfully exist within the company.

If this belief wavers, sentiment like “I don’t even know why the frontend chapter exists” can form both inside and outside the chapter. This leads to declining morale and sense of belonging, which in turn erodes competence and intrinsic motivation.

Another reason organizational mission matters so much is that running an organization isn’t like StarCraft, where you just hotkey your units and attack-move. It’s more like Overwatch or PUBG — games where diverse humans with individual decision-making abilities come together to fight toward a shared objective.

StarCraft units don’t question orders. They faithfully execute whatever command is given, even if you send naked Marines without Medics into a field of Lurkers for certain annihilation. That’s why a single player can comfortably control dozens of units with 100% compliance.

If you mistake organizational management for StarCraft, team pushback is inevitable.

If you mistake organizational management for StarCraft, team pushback is inevitable.

But in games like Overwatch or PUBG, calling out orders is critical. These are games where multiple humans form a team to achieve objectives together.

When you’re supposed to push the payload together but one teammate keeps charging into enemy lines for kills and dying, while another is left guarding the payload alone and getting overwhelmed — the game grinds to a halt. The leader needs to call out clearly: “Everyone focus on pushing the payload,” “The rest of you draw aggro from the payload while Genji takes out Widowmaker.” (Unless the team is deep in the lower ranks, this shouldn’t happen too often… I think.)

Real organizational management works similarly. Games at least provide a clear built-in objective, so there’s no need to think about goals. Real organizations have to align on goals first. Without this process, you end up with a team in name only — where one person is playing Overwatch and another is playing PUBG.

An organization's goal is the coordinates of a star everyone navigates toward.

An organization's goal is the coordinates of a star everyone navigates toward.If everyone doesn't have the same star's coordinates in their heads, the voyage will struggle.

That’s why I made sure that important values like the frontend chapter’s purpose and mission were always defined through everyone’s participation, input, and discussion. Most internal policies were also established in the same way, which I believe kept team members’ autonomy quite high.

Team members with high autonomy would work late into the night to pursue directions they believed in — without anyone asking them to. Their capabilities weren’t constrained at all; if they wanted to try something, they just had to persuade their chapter colleagues with sound reasoning. It would have been strange if it weren’t fun. (Of course, proposals did get rejected plenty of times too…)

Organizational goals — being somewhat abstract and distant concepts — are easily forgotten in the busyness of daily work. But naturally, goals you set yourself stick in your mind longer than goals imposed by someone else.

I let the frontend chapter determine its own direction. My role was simply to nudge that direction ever so slightly to ensure it benefited the company as a whole.

Communicate that a leader is not a boss, and that mutual feedback is essential

The final value I considered important was mutual feedback. I believe that a leader and team members aren’t in a hierarchical relationship — they simply have different roles. And to perform well in each of those roles, you inevitably need help from your colleagues.

A mutual feedback environment also enhances team members’ autonomy by giving them the power to influence the leader’s direction. Of course, simply exchanging feedback isn’t enough — the leader needs to express gratitude after receiving feedback and demonstrate genuine receptiveness. (And if you disagree with the feedback, just explain your reasoning in detail.)

No human is perfect. Even the most talented person has both strengths and weaknesses, and no matter how long someone has worked, they’re inevitably a beginner in areas outside their expertise.

I have clear strengths, but I also have clear weaknesses. My knowledge in areas outside frontend development — the field I’ve spent years in — is relatively limited, and I can’t claim to be an expert in everything.

I imagine the same is true for most people. A single, small human can’t possibly be good at everything in this world.

In very small startups with around ten employees, a talented leader might handle many things simultaneously like a firefighter. But as organizations grow, that becomes increasingly difficult, and failing to delegate properly can produce various side effects.

Moreover, in such leader-dependent structures, if the leader isn’t exceptionally capable, the entire organization’s performance crumbles along with them. Active mutual feedback can serve as a means to grow the leader when they’re falling short, or to hedge against the leader’s insufficient decision-making ability.

However, in traditional companies where leaders are often equated with bosses, it’s hard to establish a robust feedback culture unless the leader genuinely possesses the capacity to accept feedback and the ability to separate feedback from their emotions.

Feedback receptiveness connects to metacognition. Since metacognition is the high-level concept of “knowing what you don’t know,” it’s not easy to cultivate on your own. Most people find themselves in a state where they don’t even know what they don’t know, yet think “I know a lot” — a kind of Sophist thinking.

Paradoxically, I believe the best way to develop metacognitive ability is through team members’ feedback. In practice, as I worked in a leadership role and talked with many people, I often found significant gaps between how I saw myself and how others saw me.

Here’s my own example. The left column is my self-assessment; the right is feedback from colleagues:

| Trait | My Assessment | Others’ Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Not very emotionally volatile | I can make decisions without emotional interference | Your tone is too cold. We’d like to see more inclusion, not exclusion |

| I tend to share opinions first | I express my thoughts clearly | Your expression is so strong that it’s hard to voice opposing views |

| I don’t show personal emotions at work | I clearly separate work and personal life | You seem unapproachable and lacking warmth |

These value judgments inherently include a kind of self-serving bias, so one tends to judge oneself leniently and others strictly. Personal rapport can introduce bias as well. I’m just another human who can’t escape these biases — which is why my self-assessment was skewed positively.

But ultimately, one thing matters: a leader is in a position where they need to earn others’ trust. So rather than how you see yourself, what matters more is how others perceive your characteristics — and you need to know that clearly and respond accordingly.

My point isn’t “don’t fall into bias.” While I’m no psychology expert, I believe it’s nearly impossible to completely eliminate these biases.

What matters is the leader recognizing: “I have biases and errors,” “I’m not that perfect.”

A leader is human, so naturally there will be areas of strength and areas of weakness. But if you’re not clearly aware of your strengths and weaknesses and try to micromanage beyond your competence or grab excessive decision-making authority, the result can be worse for the organization overall — and it can create problems in earning team members’ trust.

Humans tend to think in ways biased by their experiences,

Humans tend to think in ways biased by their experiences,so if your early career was spent in a control-heavy organization, your leadership may unconsciously lean toward control as well. This is why metacognition matters.

A leader isn’t someone who controls team members. They’re someone complementary to them. After all, the role of leader can only exist because team members exist.

So you need to learn how others perceive you through their feedback, and by taking appropriate action items, shape how you appear to your team in the right direction.

But stepping out of the ideal and into reality, you’ll find that in most organizations where feedback culture hasn’t taken root, people are afraid to transparently share their thoughts about others. Especially in Eastern cultures that value the group over the individual, a “leader” is often equated with a “commander” — so breaking this preconception is important.

That’s why leaders need to actively communicate that they want feedback, and deliberately — even exaggeratedly — demonstrate a receptive attitude.

I held coffee chats with everyone in the frontend chapter every two weeks, and at the end of each session, I always asked for feedback. I consistently made explicit statements like: “Giving me feedback helps me grow,” “I’m not perfect either, and I want to improve my weaknesses through feedback,” “Just as you want to grow, I’m just another developer who wants to grow too.” My goal was to make team members think, “This person is genuinely obsessed with feedback…”

Of course, extracting meaningful feedback every two weeks isn’t easy — most sessions were a parade of “Nothing in particular.” But by persistently maintaining this practice, I was able to receive meaningful feedback from time to time. (Like being told to come in earlier in the morning…)

When I received feedback I resonated with, I’d establish action items to address it and always share the results afterward. Many things didn’t actually improve, but it was a way of actively signaling that I didn’t ignore their feedback.

It varies somewhat by personality, but in an authority-oriented culture like Korea’s, giving feedback to a leader takes considerable courage. So naturally, the person receiving feedback should express gratitude for the courage it took, and demonstrate that every word was taken to heart.

Even if you didn’t agree with the feedback, always express gratitude first for the courage it took, and then explain why you didn’t fully resonate with it.

Be careful, though: reacting emotionally to feedback, or saying “thank you” but then showing no action items or sharing no follow-through. These patterns will cause team members to develop the mindset “Talking to this person won’t change anything,” and they’ll eventually stop speaking up.

If more and more colleagues start feeling this way, the organization can become like a boiling pressure cooker, ready to blow at any moment. Frustration with the leader has already built up, but people either fear speaking up or feel powerless that nothing will change even if they do.

That’s why a leader should consistently and proactively seek feedback from colleagues — continuously gathering information that helps develop metacognition: how colleagues perceive you, where you’re falling short, and what you’re doing well.

Closing thoughts

After about three years of leadership experience and reflection, the dominant feeling I’ve had is probably “…this is really hard.”

Computers are friendly companions. Give them a command and they faithfully execute it. Humans, by contrast, are wildly inconsistent in behavior and thought, emotional, riddled with all kinds of biases, and astonishingly diverse.

Of course, people with high empathy intelligence who genuinely enjoy working with others might thrive in such an environment. But I’m a capital-T on the MBTI — not particularly high in empathy intelligence, and not someone who draws energy from people. So I needed a lot of reflection and research on topics like “what makes good leadership” and “what drives people.”

For the record, my MBTI is a strong ESTJ. I don't love admitting it, but it's surprisingly accurate.

For the record, my MBTI is a strong ESTJ. I don't love admitting it, but it's surprisingly accurate.

I’m actually someone who’s good at analyzing relationships and connecting them through logical reasoning. So the approach that worked best for me was building knowledge from academic research on human psychology and behavioral principles, then observing and analyzing the people around me to test those theories against reality.

Of course, no theory explains reality perfectly — especially human behavior, which remains a largely unsolved domain with no definitive answers. All I can do is observe the various situations happening around me, ask myself “why is that person behaving that way?”, and conduct my own analysis.

Perhaps that’s exactly why I found it so difficult. There aren’t many problems in the world with predetermined right answers, but analyzing and defining something as illogical as humans seems truly, genuinely hard.

I’m still a fledgling leader with only three years under my belt, so these reflections are just the beginning. There are plenty of days ahead for this kind of thinking, and I’m in no rush.

This concludes my post: What Do People Work For? — The Psychology of Motivation.