Becoming Someone Who Survives the Market

The labor market is a game — are you ready to win?

In this post, I want to calmly lay out some of the thoughts I’ve had as a player participating in the market economy.

I’ve written a lot about personal growth, motivation, and philosophy, but this time I want to talk about something more grounded in reality. Rather than telling you “just keep working hard and things will work out,” I want to offer an agenda that might actually help in practical terms.

As a developer, you surprisingly often encounter opportunities to help — or situations where you have to help — developers with less experience than you.

Most of the junior developers I’ve met or exchanged messages with were hungry for growth, and I usually shared topics that would help them reflect on growth — things like motivation, consistent effort, and metacognition.

And when someone asked about compensation, I’d often say this:

If you grow and become a competent developer, the rewards will naturally follow.

It’s true to some extent. But rather than rewards materializing on their own just because you’re good at your job, it’s more like having the capability to seize good opportunities when they come. Being good at your job and being good at making money are slightly different things.

There are senior developers out there who’ve built solid skills through consistent effort yet receive less compensation than entry-level developers because nobody knows about them. Conversely, there are developers whose programming skills are unremarkable but who command high compensation through personal branding.

Of course, it’s true that better programming skills generally correlate with better compensation. But no matter how skilled you are, if you just sit there quietly, chances are nobody will notice. And honestly, unless you’re a truly top 1% standout, most developers at a similar level of experience are roughly comparable in programming skills.

The beautiful story of “hard work proportionally rewarded” can be motivating, but if you look closely at reality, you’ll find that things don’t work that way more often than not.

That’s why in this post, rather than talking about growth, I want to talk about something more practical: the market.

Develop a basic understanding of the market game

South Korea, where we live, is a capitalist country. Simply put, capitalism is an economic system where market participants exchange their respective values within the market.

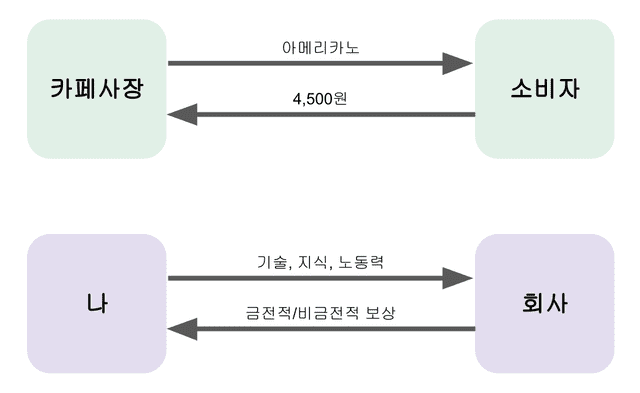

In other words, the labor market where working professionals like us seek jobs fundamentally operates on the principle of exchanging the worker’s labor — a commodity — for the company’s financial compensation.

It’s a simple and clear concept, yet we often forget it in our daily lives. The very first thing we need to do to survive in the ruthless game of the market is to change how we view the labor market itself.

The market is a game where participants make decisions to maximize their own gains. There are many game theories that model and study the decisions made in markets, but I think the Prisoner’s Dilemma most closely resembles reality.

| Other confesses | Other stays silent | |

|---|---|---|

| I confess | Both get 3 years | I go free, other gets 10 years |

| I stay silent | I get 10 years, other goes free | Both get 1 year |

The defining feature of the Prisoner’s Dilemma is that even when each individual makes the best choice for themselves, the collective outcome may not be optimal. If both stay silent, both get just 1 year. But if I stay silent while the other confesses, I alone face 10 years — that risk exists.

So both sides end up choosing to confess — the option that benefits them regardless of what the other does — and they serve 3 years together.

This is similar to how eliminating nuclear weapons would clearly benefit the entire planet, yet no country can easily make that choice. Most interactions in the market follow the same pattern — participants tend to act in their own interest rather than for the collective good.

Now let’s set aside the heavy theory and talk about something every working professional cares about, salary, to start shifting our perspective on the market.

There are no absolute winners and losers in the market

Most working professionals have thought at least once about wanting a higher salary. A higher salary doesn’t automatically make you wealthy, but it does noticeably improve your quality of life.

Many people vaguely think of salary as something that increases with tenure or through job changes, but in reality, salaries are determined by the market’s cold evaluation.

To increase your salary, you first need to clearly recognize and accept that it doesn’t go up simply because you’ve worked longer — it’s the price the market assigns to your skills and labor. We’re engaged in a transaction where we sell our skills and labor, and in return, the buyer — the company — provides us with the value we call salary.

Every interaction in a capitalist market economy starts from the transaction of exchanging value for value. The higher the perceived value of the skills and labor you provide as a seller, the more the buyer — the company — will pay.

I think demanding a higher salary without any improvement in your abilities is no different from trying to charge consumers more for a product with zero improvements, just to pad your margins. (Think about how consumers react when chicken prices go up with no justification.)

The most fundamental principle for increasing your salary in the market is: raise the value of what you’re selling — your skills and labor — before making a deal.

A labor market transaction isn't fundamentally different from buying and selling a coffee at a café.

A labor market transaction isn't fundamentally different from buying and selling a coffee at a café.

Of course, in the labor market, there’s often an information asymmetry between us (the sellers) and the companies (the buyers). If you go in unprepared, you’ll likely find yourself in a disadvantaged position, providing quality labor below market rate.

But since this is fundamentally still a market transaction, these positions can always be reversed depending on factors like information, the relative value of your product, supply and demand, negotiation skills, and market conditions.

Contrary to the belief that companies are always in a position of power and workers are always at a disadvantage, there are workers who hold the upper hand in negotiations thanks to their quality labor and information advantage. It just appears as though workers are always disadvantaged because such workers make up a very small proportion.

When someone commands a high salary, it means the value of their labor is high, demand is strong, and supply falls short. Workers at this level are desired by companies of all sizes, and companies end up competing with each other for them.

Workers who can provide high-quality labor often hold a stronger position than companies in the market. Instead of submitting resumes and going through interviews, they receive outreach from companies and gather information through coffee chats and recruiting dinners before choosing where to go. There are no absolute winners and losers in the labor market.

These are all obvious facts when you think of them as regular market transactions, but the unique characteristics of the labor market — combined with the reality that most workers negotiate from a weaker position — cause us to view this market through a slightly different lens.

The first perspective shift for surviving the market is to abandon the self-deprecating mindset and recognize that you can become a player capable of transacting on equal terms with companies — putting yourself in a state where you can engage in productive strategizing.

All market participants are selfish

Occasionally, the news makes it seem like companies and workers are enemies. Unions going on strike because companies won’t pay fair wages, or workers being laid off and threatened in their livelihoods due to poor corporate governance — these aren’t rare occurrences.

Since we’re usually on the worker’s side, it’s natural to empathize more with workers than with companies. But viewed coldly, these situations are simply a series of cooperation and betrayal among game participants fighting for their own interests.

The very concept of a labor union is a group that bands together to negotiate on equal footing with companies and secure workers’ interests. Naturally, most decisions are made in favor of workers, not companies. Conversely, companies will make decisions that favor the company over workers.

As I said at the beginning, the market is fundamentally a game where all participants act selfishly to maximize their gains within the bounds of the law. To survive in the market, you need logical judgment and a neutral perspective that can coldly analyze situations and make optimal decisions — rather than emotional judgments about good versus evil.

As sellers, we want to sell our abilities at a high price; as buyers, companies want to buy at the lowest price possible. This, too, is perfectly natural when you think of it as a regular market transaction. There’s no reason to call a worker demanding high pay greedy, and no reason to call a company offering low pay evil.

There are certainly bad actors — companies that exploit information asymmetry to lowball quality talent, or pile on work beyond what was originally agreed. These unfair practices exist.

But from the other side, there are workers who engage in quiet quitting despite receiving high salaries, demand excessive perks not in the original agreement, or show a completely different attitude after joining compared to the passion they displayed during interviews. Unfair behavior goes both ways.

Because evaluations of the other party are relative, there are no absolute heroes or villains.

At the end of the day, both companies and workers are simply equal game participants acting selfishly in their own interests. If a worker’s default position in the market is that of the underdog, we should acknowledge it and come up with strategies to flip that position.

For a successful transaction in the market, you can’t just think about your own position — you need to understand the other party’s position and psychology and propose appropriate terms. Of course, you don’t have to keep cooperating after getting burned once — think of it as a tit-for-tat strategy.

Tit-for-tat starts with cooperation but reciprocates: if the other side betrays you, you respond in kind; if they cooperate, you cooperate back. Deals between workers and companies mainly happen during compensation negotiations. You might cooperate during the initial negotiation, but if subsequent negotiations don’t go your way, there’s no reason to stay — consider looking at opportunities elsewhere.

When negotiations fall through, some people take an emotional approach: “I devoted so much to this company, how could they do this to me?” But getting emotional with a buyer who won’t pay your asking price won’t make them hand over what you want for free.

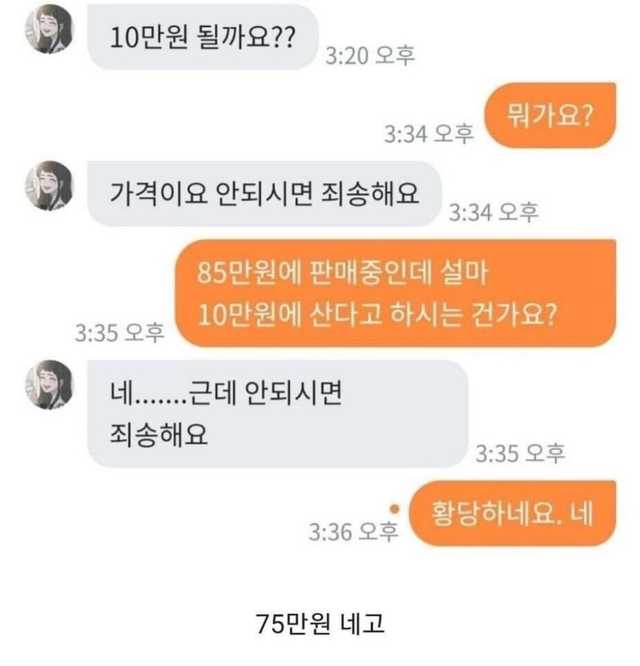

Imagine telling a café owner who wants to charge 80 price tag.

To create an effective strategy for getting the price we want for our labor, we need to understand the market game and the company we’re dealing with, and find ways for both sides to win.

The second perspective shift for surviving the market is to accept that both you and the company are simply players making decisions to maximize their own interests, and to develop an objective view that sees situations as they are rather than reacting emotionally — enabling you to coolly assess what the other party wants and how to approach them to spark buying interest.

Customer Centric

I won’t be discussing specific strategies for raising your salary by increasing the value of your abilities in this post. Everyone’s capabilities and circumstances are so different that while there may be some useful techniques, there’s no silver bullet strategy that guarantees “do this and your salary goes up.”

All I can do is offer a small nudge to help you start thinking about these strategies by shifting how you view the labor market and its basic concepts.

As I mentioned, we’re sellers — or producers — in the labor market, needing to sell our abilities to companies. In other words, we should think of our abilities as a product and consider what information buyers need to make a purchase decision.

Some might object to treating people as products and putting price tags on them. But we’re already providing labor to companies and receiving a salary in return, aren’t we? That’s the price tag on us. More precisely, it’s the price assigned to the abilities a person possesses, not the person themselves. (That’s why we use the term “talent acquisition” — hiring the talent within a person, not purchasing the person.)

Of course, factors like minimum wage laws exist to guarantee basic survival, but fundamentally, it’s just a price formed by supply and demand for a product.

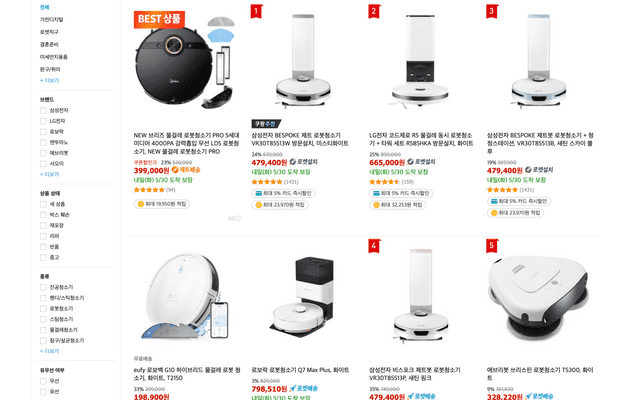

The act of companies purchasing our abilities in the labor market isn’t much different from us buying an expensive product on an e-commerce platform. For example, imagine you need to buy a robot vacuum.

Robot vacuums are surprisingly expensive...

Robot vacuums are surprisingly expensive...

When buying products online, you can’t try them out beforehand. And while you might impulse-buy something cheap, when it comes to an expensive product like a robot vacuum, you’ll be more careful to avoid wasting your hard-earned money.

So we typically read the product detail page carefully, check reviews and ratings from other buyers, maybe even look at video reviews on YouTube, and only when we think “this seems like a reasonable purchase” do we pull the trigger. (Some people just buy on impulse, sure…)

The customers buying our abilities are the same way. Buyers in the labor market can’t directly experience our abilities before purchasing. They make their buying decisions based on a simple product brochure (resume), roughly 2 hours of door-to-door sales (interviews), and maybe reviews from previous customers (reference checks).

At this stage, it’s not the product’s actual specs but the information presenting the product and others’ reviews that have the biggest influence on the purchase decision.

On top of that, human ability is an extremely expensive product — costing tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars per year — and once purchased, it’s hard to return after the probation period. The risk of a failed purchase decision is enormous, which is why it demands such careful deliberation. (This is also why companies should avoid low-density hiring out of urgency without a proper exit strategy.)

As producers, to increase the probability of selling our abilities, we need to gather information about our customers — what culture and characteristics the company has, what kind of talent they’re currently looking for, whether our abilities can solve their business or technical problems — and develop a strategy for how to sell our abilities to that specific company.

At the end of the day, the labor market is still a market. To sell our abilities to companies and receive better compensation, we need to think not only about “How can I become a better developer? (How can I make a better product?)” but also about consumer-centric questions like “What kind of talent do our customers want to hire? (What kind of product do they want to buy?)”

The third perspective shift for surviving the market is to stop viewing employment as an administrative process of taking a company’s test, passing, and becoming a member of that organization — and instead see it as an economic activity where you jump into the market, promote your abilities, and match customer needs to create buying interest.

Adopt a professional mindset

Once you’ve recognized and accepted that you’re just another participant in a market driven by capital and selfish choices, it’s time to think about how to maximize your own gains.

Earlier, I discussed three perspective shifts:

- Recognizing that workers and companies can be players transacting on equal terms

- Recognizing that both workers and companies are selfish actors moving to maximize their own interests

- Recognizing that employment is an economic activity where you sell your abilities to someone

Once you define the relationship as one between equals, the company is no longer an “employer” but a “customer” who buys your abilities. The company purchased your labor and skills, not you as a human being — so they can’t be called your owner.

Of course, some people feel like serfs because of the labor market’s nature — the product (labor) can’t be separated from the seller (worker), and while providing labor, your freedom is constrained by the buyer (company). But think about it.

What we do when we get a job isn’t really different from a famous athlete or a star instructor signing a contract with a team or academy for high pay. Either way, you’re signing a contract to provide your abilities to someone in exchange for money, and your freedom is constrained while providing those abilities.

Athletes and instructors often work even harder than the average office worker, who can fulfill their contractual obligations and go home after 8-10 hours.

Yet we call those people professionals, not serfs. It’s strange logic to say that if your job title is “office worker” you’re a serf, but if you’re a sports star you’re a professional — when both are providing abilities to others for money.

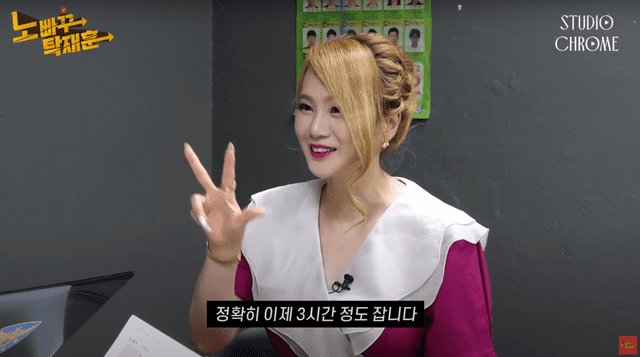

Honestly, the working conditions of a star instructor earning $10M a year are far more intense than most office workers'.

Honestly, the working conditions of a star instructor earning $10M a year are far more intense than most office workers'.But nobody would call them a corporate serf.

As long as we live as working professionals, the fact that we provide labor to others in exchange for compensation doesn’t change. The difference is in perspective: if you see yourself as a serf, you’re a serf. If you see yourself as a professional who must hone their craft to satisfy customers, you’re a professional.

I want to say that every working professional is a professional who receives compensation in exchange for their abilities — there isn’t a single amateur among us.

Our customers are obsessed with money

I said earlier that we’re all professionals and sellers who provide our skills and abilities to others for money, and that companies are our customers and buyers.

So the first thing we need to do is clearly understand what our customers — these entities called companies — exist for and what their goals are.

We go through all that trouble to identify user personas, behavioral patterns, and needs even when building a tiny MVP. Wouldn’t it be stranger if we knew nothing about the important customers who actually buy our abilities?

I can sum up what a company is in a single sentence. A company is…

💰 A group that exists to make money.

.

.

Obviously, everyone knows that

Obviously, everyone knows that

I built that up quite dramatically, but the fact that companies exist to make money is something even a kid knows.

The investors who put money into your company are people who invested massive sums expecting the company to make more money in the future and become more valuable. They jumped into the game bearing the risk that their investment could turn to dust — all for their own gains.

Some CEOs aim to realize their vision or dreams through their companies rather than just making money, but everyone would agree that as long as you’re running a for-profit organization, you can’t achieve those dreams without making money.

The reason I’m emphasizing something so obvious is that we often forget the fact that a company is a for-profit organization whose top priority is making money. Understanding and accepting this is the first step toward understanding our customers.

Because companies must make money, they will never hire us if they don’t think we’ll be profitable.

When a company signs a one-year salary contract with us, it’s essentially making a futures investment of tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars. (If you’re not familiar with futures contracts, check out my post on Everything Developers Should Know About Stock Options.)

So if you’ve signed an employment contract worth, say, 60K. Never forget that a company’s top priority is making money — not your happiness or work-life balance.

Put simply, companies approach hiring as an investment, which means they look at ROI (Return On Investment).

The expected non-financial value might include things like building organizational culture or improving team capability and morale — but these, too, ultimately serve the purpose of maintaining high productivity to generate profit. If a company goes bankrupt because it prioritized employee happiness over revenue, the employees lose their jobs too. When the company can’t make money, everyone loses.

This is the essence of our customers — the entities that buy our abilities and labor — and a critical factor we must understand as professionals seeking to satisfy them.

So ultimately, to sell our labor at a high price, we need to demonstrate that “I can generate value equal to or greater than my salary for the company.”

Think about your sales strategy

So how do we demonstrate to our customers that we can generate value exceeding our salary?

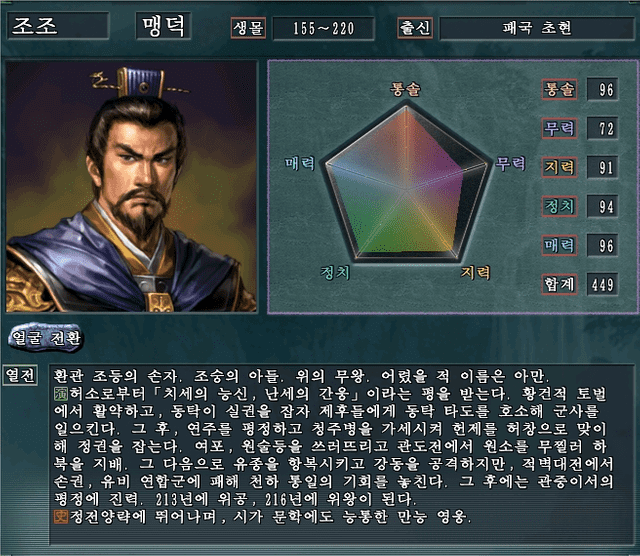

It’s a difficult problem. Human abilities can’t be neatly quantified into numbers like a strategy game character. That’s why purchase decisions in the labor market are driven more by qualitative signals — coffee chats, interviews, reference checks, reputation — than by quantitative data.

If we could express human abilities as precise numbers like in a strategy game,

If we could express human abilities as precise numbers like in a strategy game,maybe the interview process wouldn't even be necessary?

Just like the e-commerce example I mentioned, our customers have to make purchase decisions based only on approximate product information before they can actually use the product. And this is arguably the only point in the labor market where the seller can hold an advantageous position.

That’s why, as sellers, we need to think very seriously about our sales strategy — how to communicate and brand the information about the product we’re offering to buyers.

Building such a strategy starts with understanding the value of the product you’re bringing to market. You need to know your product’s strengths and the value those strengths carry before you can figure out what to emphasize and how to position yourself.

While self-reflection on your strengths and weaknesses is valuable, an even easier method is to just go out into the market and try selling your abilities.

Quality standards in the market are relative. When demand far outstrips supply, even lower-quality products can fetch high prices. When supply is abundant and demand is scarce, buyers demand higher quality.

So rather than sitting at home strategizing about how to increase your product’s value, just go into the field, make a sales attempt, and gauge the customer’s reaction and the price you’re offered. You’ll learn much faster what the market currently thinks your product is worth.

That’s why I often tell people who are thinking about growth: “Meet as many different developers as you can” and “Even if you get rejected, interviewing frequently and often is always beneficial.”

Interviewing frequently is something I can’t emphasize enough. Through the process, you learn current labor market trends, identify gaps in your product based on questions you couldn’t answer well, and if you pass and receive an offer, you learn the market price for your product.

Networking and interviewing are the best forms of market research

Networking and interviewing are the best forms of market research

Once you’ve used these methods to understand your product’s value and approximate price, take a look at this table:

| Low quality | High quality | |

|---|---|---|

| Sell cheap | Low reward / Low cost | You just lose out |

| Sell expensive | Hustler / Cost-efficient | High reward / High cost |

I think every quadrant except “high quality / sell cheap” — which is just a pure loss — is a viable strategy.

Selling a low-quality product cheaply might look like someone doing the bare minimum without expecting additional rewards (quiet quitting) or someone just starting their career. Selling a high-quality product at a premium represents highly-paid key talent at companies.

The interesting one is the quadrant where a low-quality product is sold at a high price. This could be someone who lacks substance but has accumulated years and thus a high salary, someone whose branding presents a more impressive image than their actual skills, or someone doing work that’s easy for them but appears costly to others.

Selling cheap goods at high margins is the basis of business, but in the labor market, the seller can’t be separated from the product. If a defect is discovered, things get awkward fast.

If the exaggeration is severe, it’ll get exposed during interviews or after joining. And if the inflated branding led to a price far exceeding the product’s actual value, word spreads among companies, and eventually nobody will buy.

This quadrant also represents the worst ROI for customers, so when cash flow gets tight, these are the first people to face layoffs.

That’s why I believe that in the labor market, rather than selling low-quality products at high prices, the better long-term strategy is to sell genuinely high-quality products at premium prices and build trust with your market’s customers.

It takes more fierce effort and thinking than you’d expect

So what does “high quality” mean in the labor market?

There’s no definitive answer. People who command top compensation in the labor market don’t just excel at their hard skills — they stand out across many dimensions: leadership, communication, business insight, persuasion, networking, and organizational savvy.

If you thought being a developer means you only need to be good at programming, think again. Programming skill is merely the baseline for working as a developer at a reasonable salary. If you want more, you need to develop skills beyond programming.

Of course, no one can be perfect at everything, so it’s important to clearly identify your strengths and weaknesses and build your own unique character.

This character can’t be gained through study alone — it’s a conclusion reached through endless deliberation and effort: analyzing market demand for talent, understanding your own characteristics, evaluating the competitiveness of your character itself. That’s why I said there’s no silver bullet.

The market is already full of people fighting tooth and nail to prove their value. This is especially true in industries where the gap in compensation between the top few and everyone else is enormous — I’ve seen it particularly in sports, arts, and food service.

“Here’s what you really need to understand: from the moment you start getting paid, in any world, any field, any profession — there are no amateurs. Once you start getting paid, you’re a professional. So what do you have to do? Act like one.” — Edward Kwon, celebrity chef

“If you feel nothing after losing an important match, you’re no longer a professional. It has nothing to do with character — for a competitor, the pain of defeat must always be raw and vivid. You can’t always be the winner, but you must never become accustomed to the role of the loser.” — Lee Chang-ho, 9-dan Go player

“Being a professional is about doing all the things you have to do on the days you don’t want to do them.” — Julius Erving

“Focus on what we need to do! Every one of you gets paid to play. Win the game! Don’t lose! Don’t tie! Do it right! That’s what I want. Don’t be afraid, don’t be nervous, give it everything you’ve got! Sacrifice yourselves for the team. We’re the Lotte Giants! We need to be the best!” — Jerry Royster, baseball manager

“In sports, I believe second place is the same as last.” — Sun Dong-yul, legendary Korean baseball pitcher

The IT industry I work in provides decent compensation even if you’re not number one, so the competition isn’t quite as fierce as in those fields. But if you want more than what you’re currently getting, the truth remains the same — you need that mindset, that level of fierce effort and deliberation.

A professional must always evaluate themselves coldly and put in bone-grinding effort to better satisfy their customers.

A professional must always evaluate themselves coldly and put in bone-grinding effort to better satisfy their customers.

Once you define yourself not as a mere worker but as a professional selling your abilities and skills on the market, your perspective on countless phenomena happening around you starts to shift.

If a colleague doing seemingly the same work as you is earning a higher salary, you should compare and analyze their career against yours, check whether they possess capabilities you don’t, and recalibrate your own development direction.

When it’s time to negotiate salary with your company, don’t passively wait for the company to recognize your achievements. Instead, think about how to present your accomplishments in a persuasive format. Proactively go out into the market to get offers from other companies, learn what the market values your skills at, and consider whether you can use that information as a negotiation tool.

Not doing any of this is like someone who wants to run a business but just sits in their store without any promotion, waiting for customers to walk in. Whether it’s handing out flyers, developing new menu items, or paying a commission to get on a delivery platform — you have to do something to attract customers. And when customers increase, you can raise your prices per supply and demand, right?

People envy the star instructor earning $10 million a year but don’t focus on the fierce effort and deliberation behind it.

But there’s no such thing as a free lunch. No shortcuts either. If you want to succeed, you have to consistently strengthen the marketability of your skills, analyze your buyers’ needs, and go through the process of actually selling yourself — getting knocked around and learning from it.

Just do it as a professional, not a serf.

Closing thoughts

Over the past few years, developer compensation has risen rapidly, making it seem like getting a developer job automatically meant great benefits and high salaries. I even heard recently that an acquaintance of mine started studying development — so this perception is still alive and well.

It’s true that as the IT industry grew, demand for developers gradually increased while supply fell short. Back when I was in college in 2015, the popular engineering majors were the “Big Three” — electrical, chemical, and mechanical engineering — and computer science wasn’t particularly sought after.

Then a certain company dramatically raised developer salaries and started a war to vacuum up developers from the market. Other companies, well aware that supply was woefully short relative to their demand for good developers, had no choice but to join the chicken game of salary escalation. (I think this was a kind of FOMO phenomenon.)

But as of 2023, things are very different. As developer compensation rose rapidly in recent years, the perception of the developer profession improved, computer science programs gained prestige, bootcamps proliferated as a new business model, and the supply of developers in the market increased.

Then an economic downturn hit, and suddenly demand isn’t keeping up with supply. It might still look like demand for developers is high, but look closer and it’s not.

Labor prices have downward rigidity — once they go up, they don’t easily come back down — so even when demand drops, it’s hard to suddenly lower prices.

Our customers end up paying above the equilibrium price naturally formed by supply and demand, so they become more selective about high-quality products. This leads to involuntary unemployment — layoffs or inability to find work — and wage polarization among developers.

Sellers providing high-value labor receive more compensation, while sellers providing low-value labor find no buyers at all or receive even lower offers than before. (It’s easier for a company to spend $100K on one highly capable person than to hire three less capable people at the same total cost.)

These market changes are critically important for developers, especially those just starting their careers.

Looking at the stock market might make it seem like the economy is recovering, but nothing has actually been resolved — it’s a difficult market for everyone. In this environment, I simply cannot bring myself to say “just work hard and the rewards will follow.” That advice worked when times were good, not now.

Yet amid these rapidly changing market conditions, there’s plenty of talk about how learning TypeScript, React, and Next.js leads to employment, or how Rust is the latest trend — but hardly anyone talks about these practical realities. I’m not sure why.

Technology matters, but you need a stable life first before you can enjoy the technologies you love. Learning driven by intellectual curiosity rather than survival is far healthier for your growth.

I hope many developers never forget that before being a developer, you’re a working professional and a market participant. I hope you develop the cold-eyed market perspective needed to analyze and respond to difficult situations like the current one.

That wraps up this post on becoming someone who survives the market.