What Is Abstraction, Really?

More important than implementation: the essence of abstraction that developers should think about

In this post, I want to talk about abstraction. Abstraction occupies an important place not just in application design but across all of computer science. Yet the concept of abstraction is itself so abstract that many developers who are just starting out find themselves deeply confused by it.

Abstraction shines especially when you need to build something with a complex structure, making it an essential concept when designing large, complex applications.

I briefly mentioned abstraction in my earlier posts A Fun Look at Object-Oriented Programming and Functional Thinking That Breaks Conventional Mindsets, but since abstraction isn’t a concept limited to OOP and wasn’t the main topic of those posts, I didn’t go deep into it.

Many people understand abstraction only as “extracting common elements.” Strictly speaking, this isn’t wrong — but it’s just one specific technique for defining something abstract. It doesn’t explain what abstraction fundamentally is.

If you try to understand abstraction from this angle, when someone asks “Why is abstraction needed in programming?”, you’ll only be able to give a narrow answer like “You can extract common parts to improve reusability.” (This is actually a question I frequently ask in interviews.)

To properly understand abstraction, you need to step away from programming’s definition and think from the ground up about what abstraction fundamentally is and why we need it.

Expressing Complex Things Simply

Let’s start from the most fundamental question: what exactly is abstraction?

As you know, the term “abstraction” isn’t exclusive to programming. It’s used in mathematics and programming, but also in art and architecture. The most famous abstract painter is, of course, Picasso.

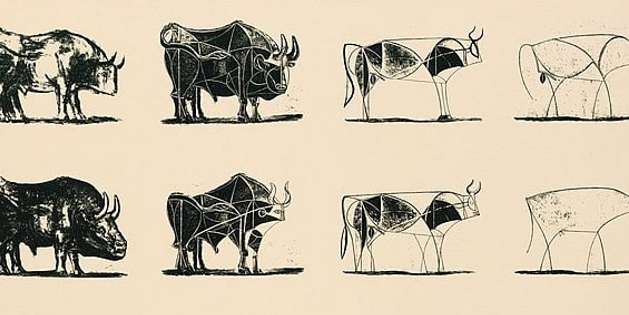

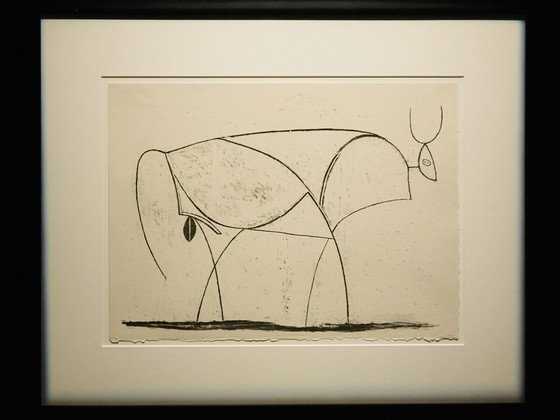

Picasso's drawing that removes all complexity from a bull and leaves only its most essential features

Picasso's drawing that removes all complexity from a bull and leaves only its most essential features

As you can see, an abstracted subject emphasizes the features that represent the subject’s essence. In simpler terms, individual details are stripped away and the characteristics that define the subject itself are strengthened.

Picasso’s bull drawing can correspond to anything that has the essence of “bull.” Whether it’s a dairy cow, a Korean hanwoo, or a charging bull — none deviate far from that form. In reality these bulls all look different, but they don’t stray from the essential form of what a bull is: four legs and horns on the head.

It’s like how every individual human has a different face, voice, and personality, but fundamentally we all have two arms, two legs, and one head. That’s the essence of the subject.

When you express only the essence and remove the details, the expression inevitably becomes simple. Something that expresses only 10 core features is naturally simpler than something expressing 100 granular ones.

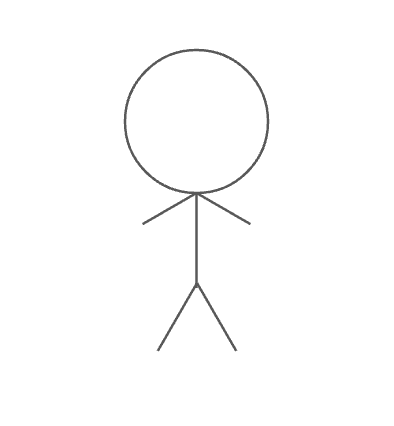

Expressed with just a circle and five lines, yet no one would mistake this for a dog or cat.

Expressed with just a circle and five lines, yet no one would mistake this for a dog or cat.This is an abstracted representation that captures the subject's essence.

Ultimately, an abstracted subject is “a simplification that retains only the core features of something complex and removes the rest.” Like the paintings of abstract artists who use simple shapes to express complex things — emotions, animals, objects — simplifying them and emphasizing only what’s essential.

And these generalized core features inevitably become what these entities have in common. That’s why OOP guides you to extract common features from objects and define classes.

If I removed the circle from my stick figure drawing, you wouldn’t know if it was a rocket, an arrow, or a headless human. Because any living human is generally expected to have a head in that position. The position and shape of the head is a defining commonality that all humans share.

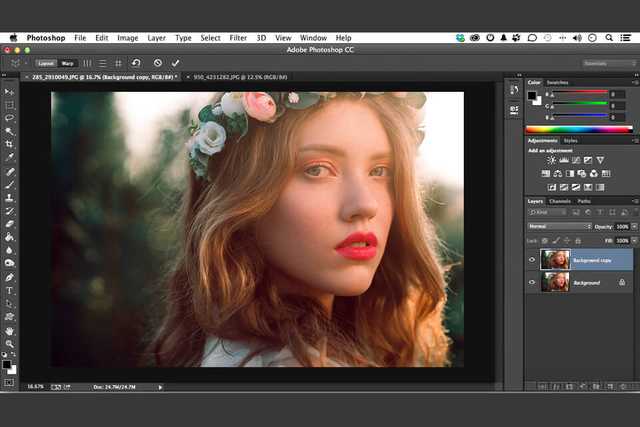

Nobody would look at this photo and think it looks natural

Nobody would look at this photo and think it looks natural

Stripping away everything except the core features of a complex subject and expressing it simply. That is the essence of abstraction.

Why Does Programming Need Abstraction?

I described abstraction as the act of stripping away everything except the core features of a complex subject and expressing it simply.

So why do we need this in programming? We’re not artists like Picasso, grasping the essence of objects and expressing them artistically.

The answer is actually very simple:

To build more complex and difficult things.

Abstraction Enables Building More Complex Things

As I mentioned, an abstracted subject takes on a very simple form because it expresses only the most essential features from its original characteristics. The key point here is “expressing something that’s actually complex in a simple way.”

One difference between artistic and industrial abstraction: in art, abstraction removes the complex parts, while in industry, abstraction hides them.

In other words, by hiding concrete, complex implementation behind a simple form, you enable users of your module, component, or product to utilize its functionality without needing to understand the underlying principles.

Take the computers we use in daily life. Very few people understand the principles down to the semiconductor level, and even elementary school students who don’t know what a CPU is can use a computer. We can abstract “computer” as “a device you operate with a keyboard and mouse to see results on a monitor or speaker” — and that’s sufficient for use. There’s no need or reason to understand every detail of how a computer works.

A person using Photoshop to edit photos just needs to focus on how to use Photoshop. They don’t need to know how the program works internally or how the OS allocates resources to its process.

If a Photoshop user had to worry about all of that, wouldn’t “editing a photo in Photoshop” become prohibitively difficult and complex?

If editing photos in Photoshop required understanding all the principles of image processing,

If editing photos in Photoshop required understanding all the principles of image processing,the task would become far too difficult for a single person's capacity.

The fundamental concept of abstraction is already at work in cars, smartphones, urban infrastructure, administrative systems, and more. Many things we take for granted are the result of complex logic and infrastructure being abstracted away.

Thanks to abstraction, we can leverage the systems of complex modern society without needing encyclopedic knowledge across every field.

Turn the faucet and clean water comes out → The city’s water supply system is abstracted

Go to the municipal office and you can register your residence → The government’s administrative system is divided and abstracted

Press the accelerator and the car moves forward → The ECU and engine logic handling intake/compression/combustion/exhaust is abstracted

The world we live in today is built on layers of abstract concepts. Thanks to this concept of expressing complex things simply, people can focus only on what they’re responsible for, enabling division of labor and the creation of things more complex than ever before.

The semiconductor manufacturer focuses only on semiconductors. The computer assembler focuses on computers. The Photoshop developer focuses on image processing and programming. The artist focuses on using Photoshop. Because specialists in each field come together, they can build things more vast and complex than any individual could. If one person had to understand all of it to produce a product, even a lifetime of knowledge-building wouldn’t be enough to produce complex products at high quality.

These benefits of abstraction apply equally to our experience of programming. The software we build is, like products in other industries, an assembly of many small modules contributed by countless people around the world.

Frontend developers like me mostly use libraries and frameworks like React or Vue to build web applications. Combining these small programs to create complex applications is nothing unusual.

Honestly, even without knowing the detailed inner workings of a JavaScript engine, knowing the general syntax of JavaScript and how to use the React library is enough to build applications.

In the past, developers routinely configured Webpack themselves to bundle applications. Now, CLIs like CRA or frameworks like Next.js generate Webpack configurations automatically — and even hide them behind abstractions. Some developers who started recently have never touched Webpack directly. (In practice, you can build typical applications these days without any Webpack knowledge.)

Search "webpack eject" on Google and you'll see

Search "webpack eject" on Google and you'll seejust how many people try to avoid breaking the abstraction and touching Webpack directly.

Thanks to these abstractions, today’s frontend developers are freed from complex concepts like manually syncing state with UI rendering or bundling projects themselves, allowing them to focus on higher-level concerns. This has enabled the development of increasingly large and complex web client applications.

This is exactly what abstraction in programming — and in industry more broadly — gives us.

Moving Beyond “Extract Common Features”

Now that we’ve established that abstraction is a general concept not limited to programming and why the programming world needs it, let’s look at something more specific.

I said earlier that OOP’s guideline of “extract common features from concrete things to define abstract things” doesn’t fully explain the essence of abstraction. It’s just one approach to abstracting something complex into something simple.

I’m not saying this approach is wrong, but I personally don’t recommend trying to understand abstraction from this guideline. It’s simply “one way to approach a subject for abstraction.” Getting too attached to this method can actually limit your imagination about how the application might evolve, leading to designs that aren’t open to change.

Let’s look at a simple class example.

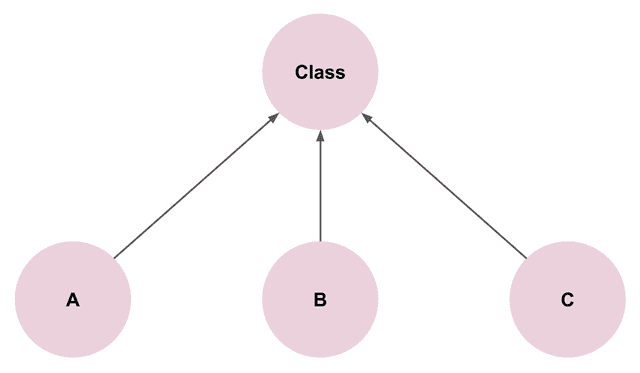

Design That Too Faithfully Reflects Current Requirements

- The requirements include objects A, B, and C.

- Their commonality is that they’re all pink circles; the difference is the letter in the center.

- Define a class: pink circle shape + injectable center letter.

This class can cover all cases in the current requirements, so it looks well-abstracted. And indeed, this design faithfully satisfies the current business requirements — no problems.

But problems always arise when changes beyond the current spec come in.

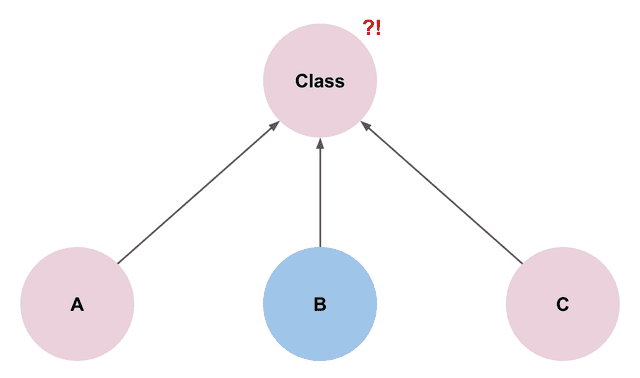

"PO/PD: Can you make object B's color changeable?"

"PO/PD: Can you make object B's color changeable?"

My face when I hear the requirement.jpg

My face when I hear the requirement.jpg

I’m sure many of you have experienced this. In fast-moving business environments, specs changing is completely natural — and this happens regardless of whether you use OOP or FP.

In the example above, making the object color changeable is a simple change, so it might not seem like a big deal. But you know better than anyone that real-world changes are far more severe than this. (Move the building 1cm to the right…mmph)

There are many conditions that define “good code,” but a representative one is code that’s “open to change” — code that can be extended without modifying the existing design, even when requirements change. Business requirements inevitably shift with market conditions, and if the code can’t keep up, you can’t deliver real business impact.

But the code in our example couldn’t handle future changes, creating a situation where the class must be modified. And since classes, being abstract representations, are likely reused in many places, fixing just the class won’t be the end of it.

Why Did This Happen?

Why wasn’t this class designed to be open to change? There are many possible reasons, but I think it’s “because the design was too faithful to current requirements.”

Of course, we develop products to match business requirements, so designing for current requirements is natural. But every developer wants future-proof designs — extensible, open to change, maximizing code reuse no matter what new features come along.

But if you abstract by extracting commonalities from your current specs, even the abstracted concept is likely to be designed reflecting only “the present requirements.”

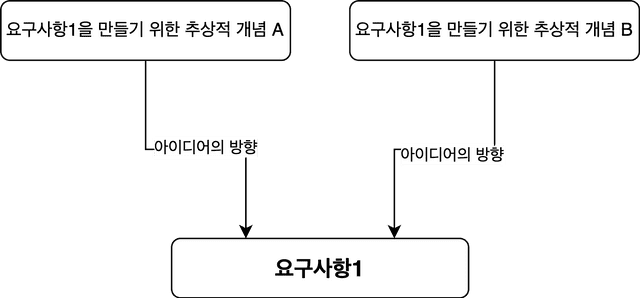

Since you're abstracting from the requirements you've been given,

Since you're abstracting from the requirements you've been given,the abstracted concept naturally tends to reflect only current requirements

You can certainly create designs open to change even when abstracting from details. Design patterns commonly discussed in OOP — SOLID principles, and more specifically IoC and DI — are methods for achieving exactly that.

But to create designs open to change through this thinking process, you inevitably need the developer’s experience-based ability to predict the future and business domain knowledge. You need a sense for which parts are likely to change frequently so you can design those parts flexibly.

Moreover, the common instruction “extract objects’ commonalities” says nothing about these design patterns, so developers have to learn them on their own and apply them appropriately.

Experienced developers might think “just do it, what’s the big deal?” — but for beginners, looking at current requirements and thinking “this part is likely to change later, so I should design it to accept injected functionality from outside” is really not easy.

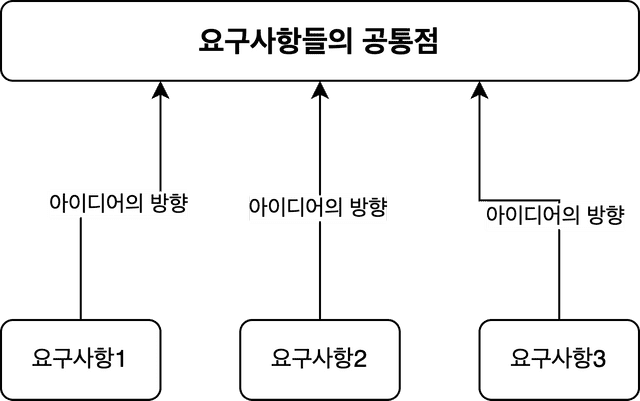

So the direction I want to suggest is not defining abstract things from concrete things, but the reverse: try thinking of the abstract things first.

Think about what components are needed to achieve the concrete requirements

Think about what components are needed to achieve the concrete requirements

Composing Abstract Things to Build Concrete Things

If you’re accustomed to the conventional abstraction approach, “define abstract things before concrete things” might feel unfamiliar. But this concept is neither new nor strange.

Earlier, I explained that abstraction hides complex things to make them appear simple, and that thanks to this, we can live in modern society without knowing all the knowledge that constitutes it.

Application design is the same. Instead of asking “what are the commonalities of these concrete implementations and how do I abstract them?”, you should ask “which parts of the concrete implementation should I package as separate components, and how should I let developers assemble these components so they can comfortably use my code without knowing more context than necessary?”

The result may be similar — common aspects of concrete concepts end up being abstracted — but the direction of thinking is the exact opposite of extracting commonalities.

Let’s say we need to build an iPhone. Approaching it by extracting commonalities from objects, the thinking flow would go something like:

All iPhone models have a way to go home (commonality)

iPhones can be divided into those with and without a home button (difference)

Then maybe I add a parameter to show or hide the home button? (implementing the difference)

interface Props {

showHomeButton: boolean;

}

const IPhone = ({ showHomeButton }: Props) => {

const [isHomeScreen, setHomeScreen] = useState(false);

const moveHome = () => setHomeScreen(true);

if (showHomeButton === true) {

return <HomeButton onClick={moveHome} />

} else {

return <HomeGesture onSwipeUp={moveHome} />

}

}The concept of composing abstract things to build concrete things remains the same regardless.

Something like this, roughly. At first glance, it handles the current requirements well. iPhones do come in older models with a home button and newer models without one.

But what if later (unlikely as it may be) Apple releases an iPhone with a dial-style home button? This iPhone has no concept of tapping or pressing — you can only rotate it.

Naturally, our function wasn’t written with that in mind, so now we’d need to add a homeUIType parameter and remove the now-meaningless showHomeButton.

type IPhoneHomeButtonType = 'dial' | 'gesture' | 'button';

interface Props {

homeUIType: IPhoneHomeButtonType;

}

const IPhone = ({ homeUIType, onMoveHome }: Props) => {

const [isHomeScreen, setHomeScreen] = useState(false);

const moveHome = () => setHomeScreen(true);

switch(homeUIType) {

case 'button':

return <HomeButton onClick={moveHome} />;

case 'gesture':

return <HomeGesture onSwipeUp={moveHome} />;

case 'dial':

return <HomeDial onChange={moveHome} />;

}

}Just adding one more type of trigger for going home required changing the function’s parameters and internal logic entirely. And since the parameters changed, every place that uses this function needs to be updated too.

Many developers reading this might be thinking:

Just use IoC and inject from outside for flexibility from the start — who codes it like that!

Just use IoC and inject from outside for flexibility from the start — who codes it like that!

interface Props {

renderHomeUI: (moveHome: () => void) => ReactNode;

}

const IPhone = ({ renderHomeUI }: Props) => {

const [isHomeScreen, setHomeScreen] = useState();

const moveHome = () => setHomeScreen(true);

return renderHomeUI(moveHome);

}

// By composing with IoC from outside,

// you can use various Home UIs without changing any logic inside the IPhone component.

<IPhone renderHomeUI={(moveHome) => <HomeButton onClick={moveHome} />}>

<IPhone renderHomeUI={(moveHome) => <HomeGesture onSwipeUp={moveHome} />}>

<IPhone renderHomeUI={(moveHome) => <HomeDialog onChange={moveHome} />}>I agree. The “go home” feature is an abstract capability that has little to do with the “home button” itself. The home button — the entity that triggers the go-home event — is highly likely to change depending on the phone’s design.

But as I mentioned, developers unfamiliar with this approach can easily get trapped by their existing knowledge of iPhone features or the current requirements, failing to recognize that the home button is highly change-prone. They might conflate the stable “go home” function with the volatile “home button” as a single concept, producing a tightly coupled design.

Those who immediately thought “this should be injected from outside” probably developed that insight through past painful experiences, building an intuition for which parts change frequently. In a word: experience.

But beginners lacking this insight will formulaically extract commonalities from concrete things to abstract, then ad-hoc their way through design extensions as the business evolves. It’s too easy to fall into this pattern.

Concepts like IoC and DI are things you naturally learn through study after suffering through these mistakes a few times — very few people start development with these concepts already in hand.

That’s why I recommend approaching abstraction not by extracting commonalities from concrete things, but by first thinking about what small components your concept is made of, then composing those components to build the concrete concept.

An iPhone is composed of a microphone, speaker, display, home button, etc.

How should each component be assembled?

Speakers and microphones probably don’t change position much across different smartphones.

Home buttons differ by smartphone, right? Some don’t even have one nowadays. So how should this be assembled?

This bottom-up thinking naturally makes it easier to create designs that can cover not just the concept of “iPhone” but even the broader concept of “smartphone.”

Since concrete concepts tend to reflect only the current business situation, extracting commonalities from them makes it hard to account for future changes. But when you think in terms of composing abstract concepts to build concrete ones, you naturally — almost without conscious effort — end up with designs where abstract components can be swapped in and out.

Things Worth Considering for Good Abstraction

Having covered the macro aspects — what abstraction is and how to approach it — let me now discuss some actionable considerations for when you actually perform abstraction.

I suggested using bottom-up thinking to consider what abstracted components you need to achieve concrete requirements. When abstracting this way, new questions arise: “what granularity should each component be?” and “how should I express each component’s functionality?”

You could separate concerns so each component handles a single small responsibility, but splitting too finely can create over-abstraction that makes it hard to grasp context. You might also create components whose functionality is poorly expressed, making them difficult to compose with others.

So in this section, I’ll share a few considerations I keep in mind when abstracting.

Don’t Force Excessive Context on Developers

When people talk about the benefits of abstraction, they usually mention reusability. But as I’ve said repeatedly, the greatest benefit of abstraction is making complex things appear simple.

This benefit can be found in classes, functions, and components alike. Here’s a rough example:

Prepend “I am ” to each value in the array.

const arr = ['Evan', 'Daniel', 'Martin'];

const newArr = [];

for(let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

newArr[i] = `I am ${arr[i]}`;

}

console.log(newArr); // ['I am Evan', 'I am Daniel', 'I am Martin'];Few people write imperative code like this nowadays, but I’ve exaggerated for illustration. This code uses a for loop to manually iterate the array, accessing each element by index to reassign values.

A developer reading this code would naturally pick up on these contexts:

A

forloop will repeatedly execute the inner code.A variable

iinitialized to0will increment by1after each iteration.

iis used as an array index to access each element.Template strings prepend

I amto each element’s value.

This code actually carries a lot of context. Because all a developer needs to know is whether the code properly prepends “I am” to each array value. They don’t need to know anything about indices or for loops.

What if we abstract this operation at various levels?

// Abstract only the array iteration and new array creation

const newArray = arr.map(v => `I am ${v}`);

// Also abstract the string concatenation with template strings

const newArray = arr.map(v => addPrefix(v, 'I am'));

// Also abstract the fact that map is used

const newArray = addPrefixToItems(arr, 'I am');

// Abstract even the "I am" string concatenation

const newArray = addIamToItems(arr)These code samples show progressively higher levels of abstraction from top to bottom.

The top code abstracts away the for loop and new array creation, so the developer no longer needs the context of manually initializing and managing an i variable or declaring a new array. They just need to know how Array.prototype.map works — that it iterates an array and creates a new array from transformed elements. Code abstracted this way focuses more on the developer’s intended behavior than on the step-by-step instructions for the computer, which is why it’s also called declarative programming. (Focusing on what to do rather than how to do it.)

Let’s look at a more everyday example. You’re probably already writing code like this using various libraries:

import { css } from '@emotion/css';

import format from 'date-fns/format';

const Foo = () => {

// Abstracts: creating a Date object and initializing it to today's date

const now = new Date();

// Abstracts: generating the desired string from a Date object

const formattedDate = format(now, 'yyyy-MM-dd');

return (

// Abstracts: creating VDOM objects with React.createElement

<h1 className={

css`

font-size: 1.8rem;

font-weight: 800;

` // Abstracts: wrapping CSS in a style tag, inserting into <head>, generating a class name

}>

Today is {formattedDate}

</h1>

);

}

// And all of the above behavior is abstracted into:

<Foo />The Foo component does something incredibly simple — displaying today’s date in a format like 2023-03-02. But even a component this small has an enormous amount abstracted away when you examine each operation.

If you had to read and understand all this code — or write it from scratch — to create this one component, it would no longer be a “simple” component. Abstraction makes it look simple; it’s actually not simple at all. (Just implementing React in vanilla JS is already a significant undertaking…)

But because all those behaviors described in the comments are abstracted into libraries like emotion, date-fns, and react, we can ignore these complex operations and focus solely on “rendering the current time.”

To emphasize once more: the value of industrial abstraction is making complex things appear simple, so that individual people can focus on their area of expertise and collaborate to build things more sophisticated and complex. This essential value of abstraction is exactly what we experience in our daily programming lives.

When people discuss code readability, they often talk about the number of lines. But this is less about having many lines and more about “the amount of code you need to read and analyze to understand a module’s behavior.”

Simply imagine what it would be like if all the contents of the emotion, date-fns, and react libraries were declared in the same module as the Foo component.

Opening that module with no prior knowledge, you’d struggle to figure out where to start reading, what you can safely ignore, and where in all that code a bug might be. The context forced upon the developer would be excessive.

The same logic explains why frequently used modules in an organization are published as separate packages to a registry rather than just separated within the application. Both approaches separate the code from business logic, but a package blocks or discourages developers from peeking at the source code, thereby limiting their exposure to the separated module’s context. (Of course, dependency management and cross-application reusability are also benefits of internal libraries.)

// Clearly looks like following the reference would lead to @quotalab/utils.d.ts

// So people rarely try to peek at the source

import { uniq } from '@quotalab/utils';

// This path makes it feel like you could immediately see the source

// When something seems off, people jump right to the source -> context is exposed

import { uniq } from 'utils/array';Ultimately, the fundamental reason we abstract is to create context scopes — so that other developers reading our code (or our future selves) aren’t exposed to excessive context when trying to understand behavior. Just as you don’t need to understand semiconductors to use a computer.

So the person performing abstraction needs to think deeply about what parts others need to know to understand and use the code, and what parts they don’t need to know at all.

Thinking About Expression

If good abstraction means hiding detailed code so that developers can understand behavior without looking inside, then the next question is: how do we express a module’s internals to the outside world so that developers using it can reasonably infer its behavior without peeking at the source?

There’s a common joke about people not reading product manuals. The reason this meme works is that products are designed so users can roughly predict how to use them without reading the manual cover to cover. Paradoxically, the fact that you can use a product without reading the manual means it has a UX pattern that’s familiar to everyone.

I'm the first to admit I don't read manuals for simple devices.

I'm the first to admit I don't read manuals for simple devices.I just now learned there's a warranty card in there.

Most products can be figured out by pressing a few visible buttons and tinkering. I never even opened the manual for a monitor I bought three years ago, yet I had no trouble connecting and using it.

If anything, a product whose usage and behavior can’t be inferred at all without reading the manual — wouldn’t consumers reject it for being too difficult and unintuitive?

The modules we build should be the same. Think of the manual as the source code. The developer performing abstraction should clearly express the module’s behavior, inputs, and outputs so that users can infer how to use it without reading the source.

Two primary tools for expressing internal behavior to the outside world:

Names of variables and modules

If it’s a function or class: input and output types

function addDays(date: Date, amount: number): Date;This is the definition of addDays, a function from the date-fns library. The name alone tells you it adds “days” to something. It takes a Date and a number as input and returns a Date — so you can infer it returns a new Date object with amount days added.

I don’t know exactly what happens inside when I call this function. I can guess it probably uses Date.prototype.getDate to get the day and add amount, but I don’t need to know any of that to use it.

All I need to know is: “this function gives me a new Date object with the desired number of days added.” And I can infer that from the function’s name and input/output types.

But what if the name and types looked like this instead?

function add(a: any, b: any): any; No way to tell what this thing does...!!!

No way to tell what this thing does...!!!

The name add suggests it adds something, but I can’t tell what it adds or what it returns. Because this function isn’t faithfully expressing its internal behavior through its types or parameter names.

Would you trust this function and use it? Setting trust aside, you might not even be able to figure out what it does — and just skip it entirely.

Even if you do use it somehow, you’d have to read the source code to understand the function’s behavior, losing the very benefit of abstraction: hiding complex context.

Beyond this example, things like having too many parameters, or a function name that expresses context unrelated to its actual behavior, can also prevent developers from easily inferring the function’s role.

The importance of expression applies universally to anything exposed outside a module — classes, variables, and more. It’s the foundation of design that shows consideration for other developers who will use your code, or your future self.

Controlling Input Freedom for Good DX

If you’re comfortable with expressing an abstracted module’s behavior to the outside world, it’s time to think deeply about the DX (Developer Experience) for users of your module.

Many factors contribute to DX, but one I care most about is: “how much functionality should I expose?” This decision affects the effort users need to invest, the amount of context they must absorb, and the potential for human error.

For example, imagine building a simple button component:

const Button = ({ children }: PropsWithChildren<unknown>) => {

return <button>{children}</button>;

}This component doesn’t expose much functionality — it’s what you’d call a “closed” component. Since it only provides the ability to inject children, users have very limited freedom.

While children can be freely injected through composition, changing the button’s type, adding a click event handler, or anything else is simply not possible.

But because the provided functionality is so limited, users barely need to think about how to use this component.

const Button = (props: ComponentProps<'button'>) => {

return <button {...props} />;

};This component, on the other hand, accepts all the properties that React’s button component natively provides. Users can use any button property they want, giving them high development freedom.

But because the component provides so many properties, users are continuously exposed to contexts that may not align with their purpose. I often describe this as “the component forcing decisions on the developer.”

From the creator’s perspective, you can’t predict every way users might use your module, which increases the risk of bugs or use cases that deviate from the design intent.

In other words, by controlling the module’s input range, the developer who creates the abstracted module can also somewhat control how users interact with it. So input design directly impacts the DX of developers using the module.

This type of consideration mainly arises when building internal libraries that many developers share. Design systems add even more complexity because you need to incorporate the designer’s intent when designing interfaces. (The more the code properties align with those defined in Figma or Framer, the lower the communication cost between developers and designers.)

There’s no correct answer for whether to open up or restrict a module’s inputs. It depends on the users’ expertise, the module’s purpose, and whether it targets a general audience (like open source) or a limited group (like an internal library).

The concept of shaping user experience by controlling the scope of provided functionality isn’t limited to code — it’s everywhere in daily life.

People with professional audio knowledge can leverage a synthesizer's vast features in the right contexts,

People with professional audio knowledge can leverage a synthesizer's vast features in the right contexts,but without that knowledge, a digital piano with limited features may be more appropriate for the purpose.

A synthesizer lets you directly manipulate audio waveforms to create any sound you want, offering infinite freedom. But hand one to someone without professional audio knowledge and they’ll probably give up and sell it on the secondhand market.

Moreover, such complex equipment is sometimes sensitive to voltage — careless use could damage it.

For someone without professional knowledge or who simply doesn’t need that much freedom, a digital piano — with limited features but accessible to non-experts for producing beautiful sounds — may be the better fit.

This isn’t about exposing more features just because experts know more. It depends on the context in which the tool is used and whether the user needs to understand its inner workings. Someone who just wants to play piano has no need for a complex, feature-rich synthesizer.

Beyond instruments, examples of this concept abound: manual vs. automatic transmission, cellphones vs. HAM radio transceivers, C vs. JavaScript — tools with similar capabilities but different ranges of exposed functionality based on purpose and user persona.

We must be careful not to implement a wide range of inputs that force unnecessary decisions on users who don’t need to understand the tool’s inner workings — or conversely, not to implement too narrow a range of inputs that limits use cases for users who need to understand the principles and reuse the tool across various situations.

As I mentioned, this requires considering the business context, organizational situation, tool purpose, and user needs — there’s no single right answer. But if you’re ever in a position to build an abstracted module that other developers will use, it’s well worth thinking about.

Closing thoughts

Every developer on Earth today exists in a close collaborative relationship with other developers. Some may work alone as freelancers or in early-stage startups, but ultimately they can’t avoid using tools that others conceived and developed. And since you’re not taking your code to the grave, the day will inevitably come when another developer inherits it.

Since the moment when someone else must read and understand the code you wrote today is unavoidable, we have no choice but to put effort into writing code that humans can understand. Even if you truly are the only person who will ever touch it — there’s no guarantee your future self will remember how every piece works.

Ultimately, abstraction in programming is the process of making things with complex underlying principles — or things easily understood by computers but hard for humans, easier for humans to understand. The methods and know-how for good abstraction may vary from person to person, but the fundamental essence of abstraction doesn’t change.

Personally, I don’t think the specific methods or know-how of abstraction are that important. As I mentioned, patterns and methods for creating designs open to change are already abundant on the internet, and many concepts are already cleanly organized. Reading them and using them a few times should be enough to pick them up.

But without understanding the fundamental value that the gift of abstraction brings us, it becomes difficult to even judge whether the information you’ve studied is truly useful or not.

Developers frequently invoke “No Silver Bullet” — the idea that no universal solution exists for all problems. As this phrase implies, not all information we encounter brings only benefits; sometimes a technical decision we make costs us something in return.

In such circumstances, developers must always coolly weigh the benefits of their decisions against the losses, and what helps with these decisions is an understanding of the fundamental value that the technology provides.

Of course, what I’ve written in this post isn’t the definitive answer. These are simply the thoughts I’ve developed while working as a developer, and I imagine tens of millions of developers worldwide each have their own definitions arrived at through their own deliberation.

I hope these reflections contribute even a little to the definition of abstraction you’ve arrived at, or will arrive at in the future. This concludes my post: What Is Abstraction, Really?