What I learned about growth and leadership at Toss

In an environment of autonomy and responsibility, how did I grow?

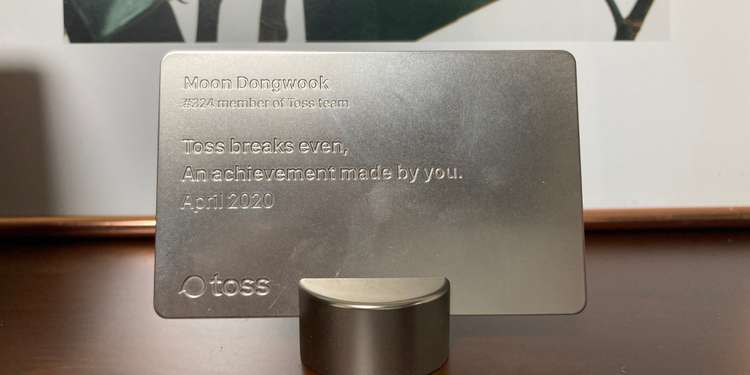

In this post, I want to casually write about my experiences and realizations from the 2.5 years I spent at Toss. I actually left Toss back in March, but between getting settled at the new place and dealing with personal stuff, three months flew by before I could finally sit down to write this retrospective.

After working as a developer for about 7 years and bouncing around different companies, my time at Toss definitely stands out. The culture was unique, my colleagues were brilliant, and I personally got the opportunity to grow from just being another developer to someone who could help grow the entire team.

How does Toss work so fast?

Starting around late 2021, I got feedback from people around me that I should stop hanging out with only developers and meet people from other fields. So I started having coffee chats with various folks - C-level executives, HR people, VCs doing investment screening, and others - where we’d ask each other questions about what we were curious about.

After several of these coffee chats, I’d sometimes visit their companies to meet the developers directly, suggest solutions to their technical challenges, and if I was curious about their business, I’d even get the chance to meet co-founders for deeper conversations. (Reading this back, it sounds kind of like dating)

I got asked a lot of questions during this process, but aside from technical stuff, the question I heard most often - and usually right at the beginning - was this:

In the IT industry, Toss has a somewhat two-sided reputation. The positive image is that it’s a team that works really well and fast. The negative image is that it’s a sweatshop with too much work.

Of course, from an employee’s perspective like mine, both working well and having personal time are important, so I’d weigh those two factors. But for people running companies or investors who’ve put money in, they’re naturally more interested in the first factor - “how to work fast and well” - so that question really meant “how can you work that fast and that well?”

DRI culture where you chart your own path

DRI (Directly Responsible Individual) is exactly what it sounds like - the person with final decision-making authority on a matter. This concept was first introduced to Apple by Steve Jobs, and it’s deeply embedded in Toss as well.

Personally, I think the driving force behind Toss’s fast pace is a culture where each person’s final decision-making authority as a DRI is tremendously respected. At Toss, decision-making power isn’t concentrated in the CEO - it’s distributed across the entire team.

In reality, Toss is a place where leaders can’t easily dictate a product’s direction. That’s because the DRI for each product belongs to the silo building that product, and specifically to that silo’s PO (Product Owner).

Of course, the CEO’s authority definitely exists at Toss, and the weight of the CEO’s words is heavier than others’. But what made Toss different from other companies was that you’d often see POs fighting with the CEO, and the POs would frequently win. (Watching a CEO and PO duke it out to the death isn’t something you typically see at companies of any significant size)

At Toss, being a DRI is like a sacred, inviolable zone. Having a DRI means your colleagues trust your abilities in that area, and losing your DRI means losing your colleagues’ trust and becoming someone the team doesn’t need anymore. So everyone fights tooth and nail to defend their DRI by earning trust from colleagues and trying to help the team.

In other words, even if you’re the CEO, if you try to crush and overturn someone’s DRI with leadership authority, the reaction won’t be “Well, the CEO wants it, so I guess we have to…” but rather “Who the hell are you to threaten my DRI?” At Toss, messing with someone’s DRI tends to really piss people off. (Crudely speaking, you might trigger someone’s rage button)

That’s why I say that at Toss, even the CEO - the company’s owner - can’t easily tell product development what to do. In fact, there are cases where a PO pushed forward with an item the CEO said not to do, and succeeded. These successful experiences accumulate and make the culture of respecting DRIs even stronger.

Of course, the CEO has more business insights than POs because of years in this domain, but since the DRI for product direction belongs to that silo’s PO, the Toss CEO usually plays more of an advisor role.

And thanks to this DRI system, each silo can determine their product’s direction themselves, develop it, observe the results, and iterate to evolve the product. Since there’s no pointless reporting or checking procedures in this process, the people making the product can decide “I want to make this!” and develop something like the Disaster Relief Fund in just a day or two.

I felt that the reason Toss can work fast and have fun doing it starts with this complete delegation of authority. Since it’s not about someone ordering you to make something, but team members coming up with their own ideas and evolving the product, the level of attachment to the product can’t help but be high.

A culture tolerant of failure

Toss is an organization that’s very forgiving of failures from new attempts. There was even a core value about having the courage to fail fast, and they held events like Failure Party where people shared their failure cases across the company.

The reason for this culture is pretty simple - to provide an environment where people can try new things without fear of failure.

Physicist Safi Bahcall, in his book Loon Shots, says that one formula for success is to rapidly and frequently attempt projects that the majority ignores and neglects. As these attempts accumulate, you eventually cross a critical threshold, and that’s when you can finally shoot moon shots.

An environment where you can attempt projects that many point fingers at and not be criticized for failure is what ultimately creates moon shots

An environment where you can attempt projects that many point fingers at and not be criticized for failure is what ultimately creates moon shots

Toss created an environment where you can comfortably shoot these loon shots. The focus isn’t on the fact of failure itself, but on recognizing what was learned from the failure and sharing it with others so the same failure doesn’t happen twice.

Of course, sayings like “failure can’t be prevented” or “you grow by using failure as a stepping stone” are things many people already know, but actually infusing a culture that doesn’t fear failure into an organization is harder than you’d think.

That’s why Toss runs campaigns like Failure Party to internally promote “how tolerant we are of failure,” or has the culture team and leaders constantly talk about how “it’s okay to fail.”

In other words, to establish a culture where organization members don’t fear failure, you can’t just not criticize someone when they experience failure - you need more proactive actions alongside that.

The truth is, most people have experienced more cultures that dismiss failure rather than encourage it throughout their lives, so even with these proactive actions, a culture that doesn’t fear failure won’t take root overnight. This kind of culture slowly seeps in through efforts to build it being consistently performed from the moment the company is founded until the day it shuts down.

Plus, culture has a kind of inertia that tries to maintain the current state, so introducing it midway costs more than building it from the start. If you want to establish a culture that doesn’t fear failure in your team, you’ll need to continuously think about and perform actions that are at least more radical and proactive than Toss’s.

The CEO also works to maintain the culture

But settling these kinds of cultures into a typical startup isn’t easy. That’s because corporate culture is most influenced by the CEO, and from the CEO’s perspective, handing over DRIs to individual contributors or just watching team members fail requires quite a bit of courage.

Usually we vent this kind of not-quite-complaint over drinks with friends:

Our CEO micromanages even the tiniest details, it’s exhausting… Do they not trust us…? If this is how it is, why did they hire me?

Of course, I sympathize with this. Generally, CEOs are experts in management, not product development experts. Honestly, from the perspective of the PO, designer, or developer actually building that product, it can be annoying and frustrating to have someone who isn’t even an expert tell you what to do.

But if you flip the perspective for a moment, that’s actually more natural and human. Because the CEO is the person who can grab the biggest profit when the company does well, but conversely, they’re also the person bearing the biggest risk when it fails.

Generally, when startups receive investment, investors evaluate the company’s value, calculate the price per share based on that valuation, and invest by transferring shares. But the process of investors investing in startups is a bit different from how we normally buy and sell stocks.

To minimize investment risk, investors use methods like buying corporate bonds to lend money and later converting the bonds to shares (CB, convertible bonds), or setting conditions where they can demand the company buy back shares whenever they want or continuously receive dividends (RCPS, redeemable convertible preferred shares), or actively using clauses that let them demand their shares be sold along when the controlling shareholder sells their stake (Tag-along) as safety nets.

Especially investors with preferred shares like RCPS have priority over common shareholders in various rights, and the problem is that CEOs also hold common shares.

So if an investor with preferred shares exercises rights like receiving priority distribution of remaining assets over common shareholders when the company fails and is liquidated, or the right to force the company to buy back shares at any point during the contract period, situations can arise where the company must honor these rights even at a loss.

In other words, startup investment is absolutely not free, and if the business doesn’t go well, the CEO can definitely suffer significant financial losses too. And as you all know, these amounts aren’t pocket change.

Honestly, in this situation, delegating all decision-making authority about product direction to employees or tolerating failure isn’t easy at all. Even with employees you hired yourself, it’s hard to trust they’ll think “this is my business” like you do.

Wait, this guy's defending CEOs? Turns out he was on management's side all along?

Wait, this guy's defending CEOs? Turns out he was on management's side all along?

The reason I’m saying all this isn’t “so let’s understand CEOs’ micromanaging” - it’s actually the opposite. What I want to say is that despite shouldering these huge risks, if you want to succeed in business, the CEO must be the first to work on building a culture of trusting team members and delegating authority.

No matter how amazing a CEO is, one person can’t do everything in the world well. Plus, if you’ve recruited senior-level team members, that means they’re much more veteran than the CEO in their field, and a proper senior can definitely track business-level issues while making decisions.

In other words, it’s more efficient to delegate authority to team members and collaborate with each person handling their specialty rather than the CEO telling everyone what to do.

Of course, working together means you’ll see trusted team members fail sometimes and you might be disappointed. But once a CEO starts micromanaging because of a few failures by team members, even if your team members could do well in some areas, they’ll give up on showing their abilities thinking “they’ll do whatever they want anyway,” or in the worst case, capable employees will leave the company.

If the CEO interferes in every little thing and restricts my abilities, why would I stay here when it’s neither fun nor conducive to growth?

If this situation repeats, the company will either see all the people who actively make decisions and demonstrate their abilities leave, or become passive, and you’ll end up with a half-assed organization where employees can’t decide anything themselves unless the CEO makes every decision.

The reason I still think Toss’s CEO Seunggun is amazing isn’t simply because he works well or is smart - it’s because he recognizes these issues himself and is directly leading the culture of delegating authority.

No matter how great someone is, as long as they’re human, they’d naturally have fear of business failure, but overcoming that fear, fully trusting team members, delegating authority, and building a culture that encourages failure - that’s not normal-person-level mentality.

Of course, the Toss culture I mentioned earlier about DRIs or an environment where you can freely experience failure might not be the right answer. In fact, Toss keeps trying new things and evolving the culture too.

But whatever that culture is, it’s hard for it to take root in an organization without the CEO’s - the leader’s - attention. No matter how much team members interested in culture run around trying things, if the CEO just says “don’t do that,” everything rolls back, making their efforts rather meaningless. And even if you somehow establish a culture, if the leader doesn’t make efforts to maintain it, other team members won’t bother maintaining it either.

Problems of a rapidly growing organization

Actually, while Toss’s culture had many interesting aspects and was a new experience, the most valuable thing I experienced at this company wasn’t the culture.

The most valuable thing I got from Toss was the opportunity to seriously think about “what is a senior developer” while actually performing that role.

When I had my first salary negotiation after joining Toss, I got feedback to become someone who could grow the team, not just myself.

I’d already been thinking about what being a senior means, and I was heading in a somewhat similar direction. That’s why I was trying to gain experience helping and growing others through things like the Lubycon Mentoring Project with friends.

But I didn’t think I’d be able to exercise that kind of influence within Toss, so when I heard that feedback, I thought:

Wait, all the FE people at Toss seem to work better than me, so what exactly am I supposed to help with…?

The frontend chapter atmosphere when I joined

To understand why I thought this way, you need to know what the frontend chapter’s atmosphere was like when I first joined.

When I first joined Toss in 2019, there were only a bit over 10 frontend developers, and I remember the entire Toss team was just over 300 people. At that time, we’d just received preliminary approval for internet banking for Toss Bank, and the headcount was definitely small considering the company’s scale and value.

When we used to go around saying we'd have no more wishes if we just had 20 frontend developers

When we used to go around saying we'd have no more wishes if we just had 20 frontend developers

Back then, Toss was focused on a hiring strategy to create high talent density, with the recruiting catchphrase “Top compensation for top talent,” and they actually succeeded in building high talent density, creating what was like an elite sports team.

This wasn’t just talk - new Toss hires feel considerable pressure about their colleagues’ work abilities. Of course, there’s the sheer amount of work, but seeing how they somehow cleanly handle all that work, you can’t help but think “Can I survive here…?”

Of course, I haven’t worked at every company in Korea, so I can’t say Toss absolutely works better than other places, but it was at least the best-working organization among the ones I’ve experienced.

Toss was a magical place where once goals were aligned, just saying "everyone figure it out" made work flow smoothly

Toss was a magical place where once goals were aligned, just saying "everyone figure it out" made work flow smoothly

So I was pretty indifferent to the growth of people in the same frontend chapter, because I thought everyone in our chapter was someone who did well on their own. And as I mentioned earlier, in an environment littered with people who work well, my own growth comes first - I didn’t have time to worry about others’ growth.

Of course, technical discussions and in-house study groups were actively happening, but these activities weren’t so much about growing someone less capable than me, but more about stimulating each other and growing together. So I remember the frontend chapter back then felt like similar-level friends gathering to stimulate each other and grow together.

In other words, I can list the internal culture of the frontend chapter at that time like this:

Because there were few people, everyone knew each other’s faces and names and had high intimacy.

There was high trust in each other’s abilities, and members felt they were trusted by teammates.

Based on this intimacy and trust, there was psychological safety formed around the frontend chapter as an organization.

The emergence of the concept of junior developers

But this frontend chapter culture started changing a bit starting in 2020. I think there were two main causes - one was that the chapter size, which had been barely in the low teens, grew rapidly and fast, and the other was the emergence of the concept of “junior.”

Actually, until then the frontend chapter already had trust formed, so the very concept of needing to unilaterally help someone else grow was minimal.

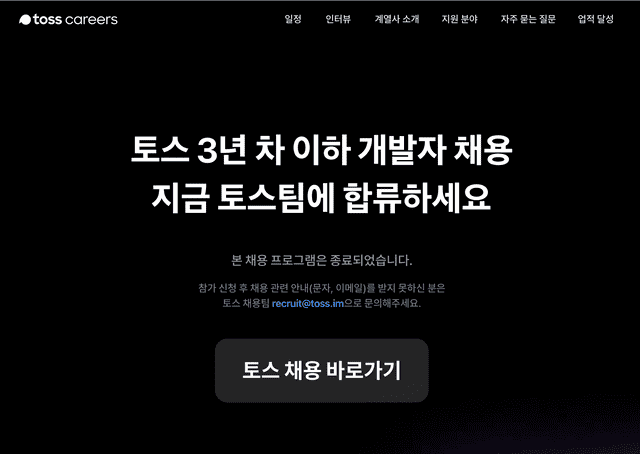

But when Toss took an aggressive hiring stance of betting on people with high growth potential even if their current skills weren’t outstanding by creating programs like NEXT Developer, Toss started having a persona of “team members who need help to grow,” and we called this persona “junior.”

The NEXT Developer job posting page says in huge letters "developers with 3 years or less experience"

The NEXT Developer job posting page says in huge letters "developers with 3 years or less experience"

NEXT Developer felt like a kind of junior job fair, and the problem was that the psychological state of people hired through a recruitment funnel that externally communicated “We’re hiring juniors!” was somewhat different from those who joined through the regular hiring process.

Of course, we were able to recruit many excellent people through that program, but I felt that the behavioral patterns of some people hired through NEXT Developer were slightly different from existing people. Typical differences I noticed were roughly like this:

Why does everyone mostly just say it’s good, it’s fine? Don’t they have anything they don’t like?

That opinion is a subjective opinion without basis, why are they just accepting it?

Why aren’t they actively participating in chapter activities?

Actually, these characteristics are typical of new hires who haven’t adapted to the organization yet, so you might think it’s not that strange. But the Toss new hires I’d experienced until then usually strongly challenged problems the existing chapter had even shortly after joining, or actively contributed to in-house libraries.

It was also strange to just chalk it up to differences in skill or years of experience, because even among people hired through the same NEXT Developer funnel, some showed these behavioral patterns and some didn’t. So I thought about what caused these differences in proactivity and organization adaptation time.

Why are these people so passive?

Fortunately, this problem awareness wasn’t just mine but also shared by several other frontend developers, and we talked about whether these behavioral differences might be differences in hard skills - differences in confidence that they’re doing their job as a developer in this organization.

So the chapter proactively promoted study groups, offline code reviews, pair programming with mates, etc. to level up developers’ hard skills.

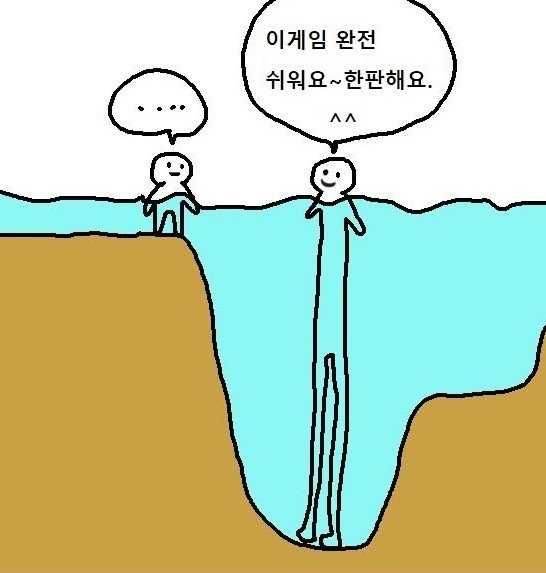

But there was one trap here - the technical level of these activities was often geared toward team members with good hard skill abilities. Since the frontend chapter until then had been an organization pursuing growth together, it was easier to select topics like abstraction and algebraic effects that everyone could newly learn, discuss, and grow from, rather than foundational content everyone already knew like Promises and React.

It's like a game full of veterans with a few newbies thrown in

It's like a game full of veterans with a few newbies thrown in

The problem here is that when discussions go on about content that greatly exceeds your knowledge, not only is it hard to absorb that knowledge in the first place, but you might even feel greater burden or self-blame thinking you can’t understand these discussions because you’re lacking.

Plus, since recruitment programs like NEXT Developer openly promoted hiring “juniors,” people who joined through this funnel tended to perceive themselves as juniors still lacking in skill regardless of their actual hard skill level, making them even more susceptible to these feelings.

Actually, I didn’t think about this at all while running study groups, but I learned about it later during 1-on-1 coffee chats. From then on, I thought this wasn’t simply a difference in hard skills but a problem of self-confidence.

While Toss aims for a challenging culture and transparent feedback culture, these things require a foundation of confidence that you’re doing at least your fair share of work within the team. When you’re uncertain whether you’re doing well or not, it takes tremendous courage to actively push your opinions or give feedback to others.

There was also a difference in psychological safety about the organization. Before, when the chapter had only about 10 people and similar technical levels, it was an environment where people quickly became close and trust formed easily.

When you know well what kind of person everyone is and their working style, even if you exchange somewhat blunt feedback, it’s easy to have a kind of certainty that this person is telling you this for the team’s development and there’s no emotion in this feedback, and this certainty can lead to psychological safety and trust in the organization.

Toss people might seem intense, but they're just really serious about work - get to know them and many are sweethearts

Toss people might seem intense, but they're just really serious about work - get to know them and many are sweethearts

But as the headcount gradually increased, we’d reached a situation where people didn’t even know each other’s names and faces, plus a hierarchy had formed within the chapter due to hard skill differences, so worries like “If I say this, will I look incompetent?” or “Is it okay for me to say this now?” naturally arose. And this situation can be a factor that lowers psychological safety about the organization.

So I thought the cause of this passive behavior wasn’t simply differences in hard skill level, but differences in confidence that you can blend in as a member of this organization, and differences in the psychological safety felt in the chapter. I thought I needed to approach it from a different direction than study groups or pair programming that could drive hard skill growth.

The emergence of F-Evangelist

As I mentioned earlier, by the time we finished the 2021 Next Developer program, the frontend chapter had nearly 60 people - it had become a massive organization compared to before.

So unlike before, people in the same frontend chapter started not knowing each other’s faces or names, and organization members’ intimacy began rapidly declining. (The era when questions like “Who is OO?” became increasingly common…)

This declining intimacy also negatively affected people’s participation in various chapter decisions, and the culture of freely exchanging feedback or even technical opinions gradually faded. And this phenomenon was happening more frequently in the junior segment I mentioned earlier.

At first, there was strong opinion in the chapter from the “return to the past” faction saying “we should try everything we can to recreate the old atmosphere,” but as time passed and headcount grew more, opinion tilted toward the realist faction that we needed to accept reality and find methods suitable for the chapter’s current size.

I was close to the realist side from the start. What I strongly argued was that even in school when everyone was the same age with similar levels, you couldn’t be close with all 40 classmates in the same class, so how can you expect the same intimacy in the current frontend chapter with even more people and hierarchy formed by hard skill levels?

In other words, the frontend chapter now needed to figure out new ways to increase intimacy and create psychological safety for an organization of over 60 people, not an organization of just about 10 people.

Even among same-age classmates, the friends you're really close with usually don't even reach 10

Even among same-age classmates, the friends you're really close with usually don't even reach 10

For that reason, Toss Core frontend chapter - which had the most people - thought about dividing people into smaller subgroups, building intimacy within them to create psychological safety about the organization, while also considering a kind of lead role that could more actively help people in those groups and infuse them with growth direction.

At Toss, there’s an organization called a tribe formed by gathering small purpose-driven organizations called silos, and originally each tribe has one role called T-Lead who rallies the developers. But since T-Leads are mainly held by backend folks, it was hard to expect them to actively suggest direction and lead on frontend stuff, which isn’t their specialty.

For that reason, until now the frontend chapter had been making decisions and executing action items at the chapter level, but as the chapter’s headcount rapidly increased and the organization’s density decreased, the frontend side also needed a role that could help team members more closely than the chapter lead.

So at first we tried to create a role named F-Lead as an homage to T-Lead, but there was worry that the word “Lead” might actually strengthen hierarchy, and the frontend chapter’s idea of a lead role wasn’t someone managing others but someone helping teammates, so there were many opinions wanting this feeling to strongly emerge from the name itself.

In other words, we expected a kind of helper role that performs work in slightly gray areas like supporting other silos, administrative work like organizational restructuring, or counseling through 1-on-1 coffee chats, creating an environment where team members can focus more on work, and helping frontend chapter members grow quickly to level up the entire chapter’s hard skills and soft skills. (While also completing all their silo work…muffled)

Through various ideation, many interesting names came up, but ultimately the role named F-Evangelist was born, and I - someone interested in chapter culture and psychological safety - ended up taking this role.

Bragging about my shit

I consistently pushed the opinion that all people in the frontend chapter organization need an environment where they can comfortably try anything and comfortably give feedback on what they think is strange, because only then can the frontend chapter develop.

When subgroups and F-Evangelist first emerged, I consistently pushed that we should focus on increasing organizational intimacy so people can feel psychological safety within the frontend chapter organization.

The top priority I was thinking about at the time was making junior members of my group see developers with more years of experience or developers in specific roles like F-Evangelist not as intimidating people but just as fellow developers.

No matter how much we removed the word “lead” from the role name to avoid creating hierarchy, since the actual actions are essentially those of a lead, I thought it was unrealistic to expect the distance or hierarchy people feel about this role to be completely removed with passive actions like just changing the name.

Plus, Toss’s frontend chapter had several developers who’d built name value through various activities, and junior people tended to vaguely think that high name value means good skills. I judged that in a situation where hierarchy was already occurring due to hard skill differences, if this misunderstanding about name value was added, it would greatly hinder creating organizational psychological safety, so I wanted to completely remove this thinking. (Being famous and being good at development have little correlation)

So the first thing I did was a “shit bragging contest.”

Generally developers aim for beautiful design, but when developing at a company, due to external factors like business situations, there are cases where you crush the design, and with tight schedules you often make bugs while rushing.

In these situations, the act of writing poorly designed code or mistakes gets expressed as “taking a shit,” and I proposed we share exactly this kind of code. It was somewhat casual and a dirty name, but I wanted a space where everyone could laugh, have fun, and comfortably disclose mistakes, so I deliberately chose a fun name instead of stiff names like “sharing debt” or “retrospective.”

My group had various segments distributed from completely new developers for whom Toss was their first job to developers with 6-7 years of experience. By running the shit bragging contest, I intended to inform everyone that regardless of years of experience, any developer can make mistakes and situations arise where you crush design, while sharing how experienced developers clean up this shit and what thought processes lead to the decision to crush design for speed.

But I made one mistake here too - what people considered shit code differed by hard skill level. Of course, for shit with relatively low resolution difficulty, active discussion happened and problem-solving methods were suggested, but for shit that’s hard to even understand if you lack hard skills, participation was starkly divided by hard skill level.

This problem had already occurred in previous study groups and offline code reviews, but when I first took on F-Evangelist, I was so eager to quickly remove psychological hierarchy that I forgot the lessons from past failures.

Actually, people’s reviews of the shit bragging contest weren’t bad, but I finished the first action item without reaching my original intention of removing psychological hierarchy.

Finding strengths

After that, I changed my approach direction and pushed a method of sharing many non-technical conversations so we could become close as person-to-person rather than developers, building up information.

So I set up mogakko sessions where people with nothing to do on weekends gathered at pretty cafes to eat delicious things and do personal work, or used subgroup weekly meeting time as chatting time, repeatedly performing various action items and observing people’s reactions. After repeating several action items like this, intimacy definitely formed within the group compared to before, and psychological safety about the organization formed.

But the issue I still hadn’t resolved was the burden junior developers carried of “I’m still lacking.” While this burden could be a great motivator for growth if it worked healthily, if this thinking became excessive, it could instead lead to drops in confidence or self-esteem and become toxic.

Around that time, I noticed a designer from my silo looking at some spreadsheet, and that sheet was the result sheet from a test called “StrengthsFinder” that the design chapter had conducted.

When you buy this book, they give you a code to take the StrengthsFinder test online

When you buy this book, they give you a code to take the StrengthsFinder test online

I don’t believe in these kinds of tests at all, so at first I thought “the design chapter did something fun again” and was going to move on, but soon I thought this test could be a good method to relieve people’s burdens. (The design chapter does surprisingly many fun things like this)

There are roughly two ways to grow - one is making what you’re bad at better, and the other is making what you’re already good at even better. But generally, developers in their growth phase tend to focus only on what they’re bad at rather than what they’re already good at, and try to fill those gaps.

While focusing on and supplementing what you’re bad at is a good growth method, if you get too absorbed in the negative thought “I can’t do this,” situations can arise where you push yourself so hard that you study or work to the point of harming your health, or feel frustrated comparing yourself with developers around you.

So I thought that if through the StrengthsFinder test we could give people metacognition so they could know “what they’re good at,” they’d learn both their strengths and weaknesses rather than just focusing on weaknesses, which might also build self-confidence.

I talked about this idea with other frontend developers, and two people sympathized and joined to try running StrengthsFinder just among ourselves. At that time, one frontend developer belonging to the design platform team had already run StrengthsFinder with the design chapter, so they greatly helped in the process of finding methods suited to the frontend chapter based on that experience.

The method of running the StrengthsFinder program was super simple - just request the company to buy the book, each person takes the test, shares the PDF test result sheet in the StrengthsFinder Slack channel, then meet offline where the facilitator explains each person’s result sheet.

Here the facilitator’s role is to create an environment where team members participating in StrengthsFinder can empathize with and remember each other’s strengths rather than just reading them. The facilitator’s action items were roughly like this:

Rather than just reading the result sheet, give examples of situations you can actually experience at Toss.

Summarize teammates’ strengths in one line to make them easy for others to remember.

Have them highlight which of their strengths they want others to pay more attention to.

Have them decide on action items that can further strengthen each other’s strengths.

The purpose of StrengthsFinder included building metacognition about what you do well yourself, but also teaching how working as one team is a process of various people with different strengths gathering to create synergy. So we didn’t just stop at knowing our own strengths, but additionally conducted activities to actively recognize and further strengthen each other’s strengths.

After running this PoC on StrengthsFinder, it explained each person’s strengths in detail and was fun, so I soon ran StrengthsFinder with the subgroup I was leading.

At that time, I didn’t want team members to feel this program was part of work, and since we were running a program somewhat removed from development anyway, I wanted to give them a feeling of escaping for a day, so we met at a pretty cafe in Chungmuro rather than the office to run the StrengthsFinder program.

The results were better than expected. Honestly, I didn’t have high expectations since these tests have no scientific basis so people might not believe them, but surprisingly everyone was happy learning their strengths, and greatly empathized with how being a good developer isn’t one single form but various forms, and that the frontend chapter is a team where people with various strengths must gather to create synergy.

Of course, I’d told team members these things a lot through coffee chats, but I was greatly impressed that running one program or campaign like this was more effective than a hundred words.

After getting good results in the subgroup, I started evangelizing at F-Evangelist meetings, explaining StrengthsFinder’s purpose and methods. The original plan was to test it first at Toss Core and export it to other affiliates if the response was good, but frontend developers from other affiliates who were lurking in the StrengthsFinder channel started spreading it on their own, and we suddenly ended up exporting StrengthsFinder.

We even wrote guidelines for StrengthsFinder facilitators for smooth export

We even wrote guidelines for StrengthsFinder facilitators for smooth export

Unfortunately I left around this time so I don’t know in detail how StrengthsFinder progressed afterward, but I heard through the grapevine after leaving that other frontend developers found it fun too, and I even heard the DS (Data Scientist) team ran StrengthsFinder. (The export speed is incredible…)

Closing

The past 2.5 years working at Toss was time that created much foundation for growth for me. While Toss has a lot of work and is intense, I think it was an organization with that much immersion in work and growth.

I got to experience what it feels like to work with capable colleagues while trusting each other, what the crazy speed of ideating a product in the morning and deploying it in the evening is like, and what the driving force that can create this productivity is - I had many experiences and thoughts.

In my final exit interview, the POM (People Operation Manager) asked me “What would Toss need to improve to make you come back?” and I answered “If I come back, it would probably be when I feel that what exists at Toss doesn’t exist elsewhere.” That’s how high my satisfaction with this organization was. (Looking back, that seems like a cool line…?)

Now Toss isn’t the 300-person startup from when I joined, but has become a mid-sized company of 2,000 people. So naturally there are parts that have changed from those days, and I feel a strange nostalgia and regret about those parts. If before it felt like doing work with really close friends whether in chapters or silos, recently it feels like it’s become a bit more like being a company employee.

But Toss can’t return to its former form now. The culture of 300 people and the culture of 2,000 people are naturally different.

So as I moved to a small startup this time, I wanted to experience directly creating that culture I loved - the one that immerses in work to create crazy productivity - and leading the product to success.

The startup I joined, Quotalab, is also enthusiastically hiring frontend developers, so if any readers want to experience introducing a culture that creates this crazy productivity into an organization and succeeding with a product based on that culture, please apply. (In IT, talent density and culture really do everything)