Everything developers need to know about stock options

Will stock options actually make you money? A realistic guide for developers

This post is going to be a bit different from my usual content - instead of talking about philosophy or technical topics, I want to talk about something that pretty much everyone working in tech has heard about at least once: stock options.

With the ongoing developer hiring crunch, more and more companies are offering signing bonuses or stock options as part of their compensation packages. But the thing is, a lot of people don’t really understand what stock options are, how they can actually make you money, or how much you’ll owe in taxes - they just accept them without thinking too hard about it.

I’ve even heard people say things like “I got 100 shares worth 100 million won when my company was valued at 100 billion, and now it’s at 500 billion, so my money must have 5x’d too!” But stock options don’t work that simply. You have to pay taxes on your gains, and the actual profit you pocket will be lower than you think. Plus, some people get caught off guard when they don’t have the cash on hand to pay the strike price or taxes.

Signing bonuses are easy to understand - the company gives you a lump sum of cash with your first paycheck after joining. It’s just regular incentive money. But stock options are financial derivatives, so if you don’t have any background in finance, they can be pretty confusing.

Sure, you could just think of them as regular stock and probably be fine in most cases. But stock options are not the same as stock, and if you don’t understand the difference, it could mess with your personal cash flow planning.

50K in stock options?

First, let’s talk about what stock options actually are. As a developer, you’ve probably gotten offers like this at some point:

50K worth of stock options

100K worth of stock options (or RSUs)

If you’ve been around the block a few times, you can probably make a good call based on your situation. But if it’s your first time seeing an offer like this, it can be pretty overwhelming. If you don’t know much about stock options, you might think:

They're giving me $50K worth of stock instead of a $5K raise? That's amazing!

You hear stories about people making millions from stock options, buying houses, and so on. And let’s be real - a 50K worth of company stock sounds pretty good, right?

But here’s the key thing: stock options are not stock.

Wait, what? Stock options aren’t stock? But companies talk about them like they are - “100 shares of stock options granted” and all that.

To understand the real difference between stock and stock options, we need to understand what this option thing actually is as a financial instrument.

Options: financial instruments with time value

An option is a contract that gives you the right to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specific price at a future point in time. In simple terms, it’s a derivative product where you’re betting on how the price will change in the future.

If you haven’t been into investing much, that might sound confusing, so let’s break it down step by step.

First, an underlying asset is something like stock, bonds, dollars, gold, or Bitcoin - assets that have economic value on their own. Derivatives like options, futures, and swaps were created to meet market needs like making it easier to trade these assets or hedging against price volatility.

For stock options, the underlying asset is stock - pretty straightforward.

The phrase “the right to buy or sell at a specific price at a future point in time” means exactly what it sounds like - you can buy or sell the underlying asset at a predetermined price in the future. Let me give you an example using corn as the underlying asset:

December 4 (current corn price: $0.50 per ear)

Me: I want to buy corn for $0.60 per ear on January 4, one month from now.

Merchant: Sure. I’ll sell you the right to buy corn for 0.10. You can decide whether to actually buy it when the time comes.

January 4 (current corn price: $1.00 per ear)

Me: Oh wow, corn went up a lot! Now I’ll exercise my option (the right to buy) and purchase corn for $0.60 per ear!

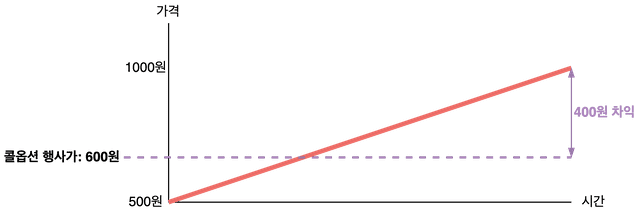

This example shows a call option - buying and selling the right to purchase something. Since I can exercise my call option and buy corn for $0.60 no matter what the current price is, the more the corn price goes up over that month, the bigger my profit.

No matter how much corn prices rise, I can exercise my call option

No matter how much corn prices rise, I can exercise my call optionand buy at $0.60, so higher corn prices mean more profit for me

If there’s a right to buy, there’s also a right to sell, and that’s called a put option.

If the option I bought from the merchant was a put option instead of a call option - meaning the right to sell corn for 0.10, I can still sell at $0.60. So with put options, the more the price drops over that month, the bigger my profit. (That’s why call options are bullish bets and put options are bearish bets)

No matter how much corn prices fall, I can exercise my put option

No matter how much corn prices fall, I can exercise my put optionand sell at $0.30, so falling corn prices mean more profit for me

Basically, options let you bet on whether the underlying asset’s price will go up or down by locking in a future price in advance.

Now, what if I’m holding a call option to buy corn at 0.50 or even lower? What should I do? There’s no profit in exercising the option, right?

Simple - you just don’t exercise your right to buy or sell. That’s why they’re called options - you have the option to exercise them or let them expire. If you don’t exercise an option, you only lose what you paid for the option itself.

Options in everyday life: apartment pre-sale rights

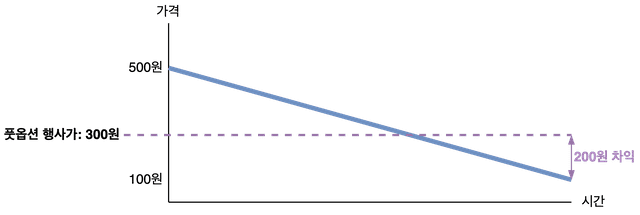

A classic real-world example of options is apartment pre-sale rights in Korea. When you win an apartment lottery, you get the right to buy an apartment at the pre-sale price, which is usually much cheaper than market value.

But having the right to buy an apartment for 300 million won means you need to actually have 300 million won in cash to use that right. If you can’t come up with the money or don’t want the apartment, people often sell these pre-sale rights to others.

Trading pre-sale rights isn't trading the apartment itself - it's trading the right to buy the apartment

Trading pre-sale rights isn't trading the apartment itself - it's trading the right to buy the apartment

In other words, an apartment pre-sale right is a contract containing “the right to buy an apartment for 300 million won by a certain date,” so people trading these rights are buying and selling “the right to buy an apartment,” not the apartment itself. That’s an option.

Aside: what’s the difference between options and futures?

A quick aside since many people confuse futures and options. They’re confusing because both involve making trades now based on predictions about future asset prices. But futures are the broader concept, and options are a type of futures contract.

Futures contracts are about pulling a future transaction into the present. So a corn futures contract would be like “one month from now, I’m going to trade corn for $0.60 - stamp stamp” in the contract. When the futures contract expires, the settlement goes through and the transaction is executed.

Since you’re literally contracting now for a future transaction, futures contracts don’t give you the choice to exercise or not exercise like options do.

Just like with options, if corn prices go up to 0.40 profit. If corn prices drop to 0.60 gets a $0.30 profit. (Futures trading is a zero-sum game - one person always wins and one person always loses)

This is the futures contract that Squid Game's Cho Sang-woo lost 6 billion won on

This is the futures contract that Squid Game's Cho Sang-woo lost 6 billion won on

But most people trading futures don’t actually want to own the underlying asset - they just want to profit from price changes. So before the contract expires and they actually have to take delivery, they sell their futures contract to someone who actually wants to buy the asset cheap, then roll over into next month’s futures contract.

Memories of negative oil prices in March 2020

So what happens if the futures contract is about to expire but there’s nobody who wants to buy the underlying asset cheap, so you can’t roll over your contract?

Hi Evan, delivery of the 100,000 barrels of crude oil you contracted for last month - honk honk~

Hi Evan, delivery of the 100,000 barrels of crude oil you contracted for last month - honk honk~

When a futures contract expires, ownership of the underlying asset actually transfers to you. If it’s stock that’s not a huge deal, but if it’s a physical commodity like crude oil or corn, the moment it expires you have an absolute disaster on your hands - this stuff actually gets shipped to some unknown port in America with your name on it. (This is why messing with futures without understanding them can really screw you)

The reason crude oil futures prices dropped to -$37 in March 2020 when COVID first hit was because of this characteristic of futures contracts. By the way, a negative price means you have to pay someone extra to take your futures contract off your hands. Around that time, the WHO declared a pandemic, and the market sentiment was:

Oh crap, a pandemic? Consumer spending will drop 👉 Production will drop too 👉 Wait…so we won’t need much crude oil to make and ship stuff for a while…?

When demand for crude oil itself drops, oil prices naturally fall. And at that time, Russia and Saudi Arabia were in an oil price war and increased production, causing crude oil spot prices to absolutely crater.

The problem was that futures contracts bought before the crash had strike prices around $20 - the pre-crash price. For these contracts to be profitable, future crude oil spot prices needed to go up. But with all these factors combined, nobody wanted to buy these futures contracts. It was cheaper to just buy at current spot prices than to buy futures contracts.

So there was an oversupply of sellers and no buyers - a truly tragic market situation.

This is the "I'll give you $37.63 if you please just buy my contract..." situation

This is the "I'll give you $37.63 if you please just buy my contract..." situation

As futures contracts couldn’t be sold and expiration dates approached, futures investors panicked about actually taking delivery of crude oil. So they started throwing their contracts away while paying $37 per contract just to get rid of them. (The ultimate panic sell isn’t selling cheap - it’s paying someone to take it off your hands…)

This is the scary situation that arises from the key difference between options and futures: “you can’t back out of the transaction when it expires.”

On the other hand, options are about buying and selling the right to transact in the future. They’re a type of futures contract, but since you’re contracting for “the right to transact” rather than “to transact,” you have the choice to exercise or not exercise your rights at expiration. In simple terms, options give you one more chance to make the final decision compared to regular futures.

| Product | What you’re trading | When it expires? |

|---|---|---|

| Futures | Contract to transact underlying asset | Transaction is executed no matter what |

| Options | Contract for the right to transact underlying asset | You can exercise the right or not |

Also, since futures require mandatory execution at expiration, it’s a zero-sum game where one person profits and one person loses. But with options, the buyer can just abandon their rights, so the option seller can end up with a pure loss.

That’s why when you buy an option, you pay the option seller a separate price for the option itself. This option price is calculated using methods like the Black-Scholes model.

Stock options: the right to buy stock

Now that we know what options are, stock options are easy to explain. Stock options are options where the underlying asset is stock, meaning they’re contracts that give you the right to buy or sell stock at a specific price at a specific time.

However, the incentive stock options we typically encounter aren’t about selling stock you already own - they’re additional incentives given when you don’t have any stock yet. So stock options just mean the right to buy stock, not to sell it. That’s why in Korean they’re called “stock purchase option rights.”

When you receive stock options, you’re not receiving stock - you’re receiving “the right to buy stock.” And the act of “using my stock options to buy stock” is exercising your right to purchase stock, which is why we say we’re “exercising stock options.”

Granting stock options

If you join a company and they promise to grant you stock options, do you get them on day one when you sign your employment contract?

Nope. Stock options aren’t something you can just hand out with a single contract. For a corporation to grant stock options to someone, they must hold a shareholders’ meeting and go through an approval process.

Corporations can only grant stock options to specific individuals after shareholder approval

Corporations can only grant stock options to specific individuals after shareholder approval

After the shareholders’ meeting resolves to grant the stock options and approve the shares to be issued or transferred upon exercise, then they can enter into a stock option grant agreement with the recipient.

Why should we care about shareholder meetings when the company handles them? Because when your stock options are granted depends on how often these meetings are held. If you join in January 2021 but the shareholders’ meeting is in December, your stock option grant date could be after that.

And the criteria for when and how much you can exercise your stock options are calculated from the stock option grant date determined by this shareholders’ meeting, not your hire date. So you need to know when your company holds shareholder meetings to estimate when your grant date will be.

Anyway, once the shareholders’ meeting approves granting you stock options, you’ll sign a stock option agreement. This agreement includes information like:

Number of shares to receive

Stock option grant method and grant date

Stock option exercise price

Cliff and vesting period

How to exercise stock options

All of this is important, but when you get this agreement, the key things to look at are the stock option strike price, cliff, and vesting.

Strike price

I mentioned earlier that stock options give you the right to buy stock at a predetermined price at a specific time. This “predetermined price” is called the strike price.

In other words, it’s literally the money you have to pay when you exercise your stock options to buy stock. If you thought stock options were just stock, you might be caught off guard when the company suddenly asks you to pay money when you want to exercise them.

Stock options aren’t free stock - they’re “the right to buy stock,” so of course you have to pay. According to Article 340-2 of the Commercial Act, the strike price must be set at the higher of either the par value (initial capital divided by number of issued shares) or the current market price.

However, companies that qualify for venture exemptions can set the strike price below market value if they meet certain conditions. Most startups qualify for venture exemptions, so they often set strike prices below market value. (Kakao was a famous case that didn’t qualify for venture exemptions, so they had to set their strike price at market value at the time of grant)

Your actual pre-tax profit from stock options is (market price - strike price) * number of shares, and you might need to have cash ready to pay the strike price when exercising. So you absolutely need to know your stock options’ strike price.

Vesting

Many of you probably know this already, but you can’t exercise stock options immediately after they’re granted.

In Korea, Article 340-4 of the Commercial Act states that you must remain employed “for at least 2 years from the shareholders’ meeting resolution date” before you can exercise stock options. Though in practice, companies usually count 2 years from the grant date rather than the resolution date. (Since the grant date is always later than the resolution date anyway, this is legally fine)

Without this requirement, employees could exercise all their stock options immediately after receiving them and quit - a classic pump and dump - and the company would have no recourse. So this is a minimum safeguard.

That’s why stock option agreements always include language like “can exercise n% after remaining employed for at least 24 months from grant date.”

How much you can exercise after 24 months depends on the company’s vesting plan. Early-stage startups sometimes let you exercise 100% after 2 years, but larger companies often split it up like “50% after 2 years, 25% in year 3, 25% in year 4.”

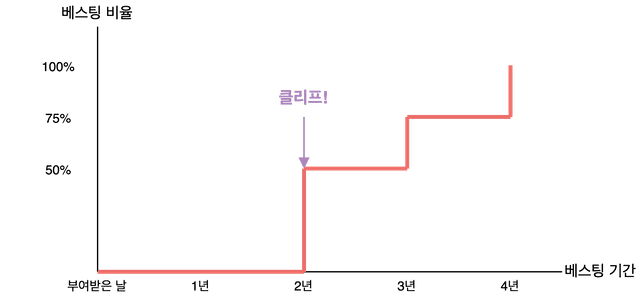

It’s important to understand that after these periods pass, your stock options transition from unexercisable to exercisable - they’re not being granted or exercised automatically, and you’re not receiving stock yet. This transition from unexercisable to exercisable status is called vesting.

The first moment when you can exercise any of your granted stock options is called the cliff. Cliff literally means cliff, and it’s called that because the amount of exercisable stock options jumps from 0 to some positive number. When you graph exercisable quantity over time, it looks like a cliff.

A sharp increase in exercisable stock options occurs 2 years from the grant date

A sharp increase in exercisable stock options occurs 2 years from the grant date

This graph shows a vesting plan with a 4-year total vesting period and a 2-year cliff.

Let’s say I join this company and immediately get granted 100 stock options after a shareholders’ meeting. Here’s roughly what happens:

I have 100 stock options but can’t exercise any of them for the first 2 years from the grant date. Not being able to exercise stock options means I can’t exercise “the right to buy stock cheap,” so for the first 2 years I’m just holding them. (But I’m definitely tracking the company’s stock price from day one…)

When 2 years pass from the grant date, I can exercise 50% of my 100 stock options - that’s 50 shares. Since there’s still a long way to go before the vesting plan ends, it’s up to me whether to exercise then. As I’ll mention below, for tax optimization it’s sometimes better to exercise in batches rather than all at once, so exercising at this point isn’t a bad choice.

After 3 years, I can exercise another 25% (half of the remaining 50%). So at this point I can exercise 75 of my original 100 stock options.

Finally, after 4 years, I can exercise all my granted stock options and the vesting period ends. This 2-year cliff with 50%/25%/25% vesting is very common, but there are various other vesting plans - some companies vest monthly after the 2-year cliff, for example.

🧐 I’ve seen places offering 1-year cliffs though?

As I mentioned, the minimum 2-year cliff is specified in Korean commercial law.

So foreign companies, especially US companies where there’s no specific law about cliffs, might offer vesting plans like “1-year cliff, then monthly vesting in equal parts.”

Exercising stock options to buy stock

Now we know when and how we receive stock options from the company and when we can exercise our rights. Let’s talk about the most important part: “the process of turning stock options into money.”

The first step in turning stock options into money is exercising them to buy stock. As I’ve mentioned many times, exercising stock options means “I’m going to use my right to buy stock cheap to actually buy the stock.”

The exercise method usually involves written notification to the company, but the exact process can vary by company, so check with your company’s person in charge or read your stock option agreement carefully.

Paying the stock option strike price

Stock options come in three main types: new share issuance type, treasury stock delivery type, and cash settlement type. Whether you need to pay the strike price depends on which type you have.

With cash settlement type, the company pays you cash equal to the difference between your stock option strike price and the current market price, so you don’t need to pay the strike price. But with new share issuance (where new shares are issued and given to you) and treasury stock delivery (where the company gives you shares it already owns), you’re exercising stock options to purchase stock, so you need to pay the strike price to the company.

If you thought stock options were just stock, you might not have the cash on hand to pay the strike price even after your options vest. This could prevent you from exercising the desired amount of stock options or even force you to take out an emergency loan. So always remember your stock options are “the right to purchase stock.”

Income means taxes!

Taxes on stock options can vary slightly by situation, so what I’m explaining here isn’t 100% accurate in all cases.

This is just to give you a rough idea of how they’re calculated - for accurate information, ask your company when you exercise your stock options.

Actually, the most important thing to understand about exercising stock options is taxes. Unfortunately, stock you receive from exercising stock options counts as income, so naturally you have to pay income tax on it. (No idea why they count unsold stock as income, but whatever…)

After year-end tax settlement...

After year-end tax settlement...

Income from exercising stock options is calculated as (market price - strike price) * number of shares, and the taxes vary depending on whether you’re still employed at that company, how much income you earn from exercising, and whether your company is a venture company.

For startups, since they’re usually unlisted with few stock transactions, they use a supplementary valuation method that calculates market price based on net asset value per share and net income value per share. As you know, startups often aren’t focused on operating profit - they just burn money to generate revenue growth. So when you calculate market price using the supplementary valuation method, it might actually be lower than the strike price.

When market price is lower than strike price, exercising stock options to acquire stock is actually a loss, so income is calculated as negative and you don’t pay income tax. (In this case you’re hoping the next funding round will bring a higher valuation from VCs)

If you’re still employed: earned income

First, taxes on stock option exercise differ depending on whether you’re still employed at the company.

If you’re still employed when exercising stock options, all profits from exercising are evaluated as earned income and added to your annual comprehensive income. So the taxes you pay are determined by Article 55 of the Income Tax Act.

| Income bracket | Tax rate |

|---|---|

| Up to 12 million won | 6% of taxable base |

| 12 million - 46 million won | 15% |

| 46 million - 88 million won | 24% |

| 88 million - 150 million won | 35% |

| 150 million - 300 million won | 38% |

| 300 million - 500 million won | 40% |

| 500 million - 1 billion won | 42% |

| Over 1 billion won | 45% |

As you probably know, this is a progressive tax applied only to the amount exceeding each bracket, not to the entire amount. So if my total income this year is 100 million won, I don’t pay 35% on the full 100 million. Instead, I pay 6% up to 12 million, 15% on the portion exceeding 12 million, 24% on the portion exceeding 46 million, and so on - the higher rate only applies to the portion exceeding each bracket.

The problem is that with just your salary, you often won’t exceed 35%, but once stock options are added, your income bracket suddenly jumps way up. So if you thoughtlessly exercise all your stock options at once, you could face a tax bomb of tens of millions of won.

That’s why when exercising stock options, it’s generally better to do it in batches rather than all at once for tax optimization.

However, according to Article 16 of the Restriction of Special Taxation Act, if your company qualifies for venture exemptions, there are some benefits:

- [Article 16-2] No tax on profits up to 30 million won per year (raised to 50 million won for stock options granted from 2022 onwards)

- [Article 16-3] If the company applies for tax payment exemption, earned income tax isn’t withheld. You can pay income tax in 1/5 installments over 5 years

- [Article 16-4] If total exercise price over 3 years is under 500 million won, you don’t pay income tax at exercise - instead you pay capital gains tax when you sell the stock

Simply put, the government is using tax breaks on stock option exercise at venture companies to encourage venture company growth. Many decently-sized startups still qualify for venture exemptions, so definitely look into this.

If your company qualifies for venture exemptions, you could pay zero income tax by only exercising 30 million won worth of stock options per year. But if your profits are in the hundreds of millions, this approach would take too long, so you might want to consider other strategies.

If you’re no longer employed: other income

Many companies only allow you to exercise stock options while still employed, but some companies let you exercise even after leaving.

In this case, since you’re exercising stock options after the employment relationship has ended, profits are evaluated as other income rather than earned income. At exercise, 22% total tax (including 2% local income tax) is withheld from the profits.

Also, if other income exceeds 3 million won per year, you need to include it in comprehensive income and file a final tax return. At that point, taxes are recalculated using the comprehensive income tax rate table above. If other income is under 3 million won you could just end it with withholding, but since stock options almost never earn less than 3 million won, you should pretty much always expect to file a comprehensive income final tax return.

Taxes are complicated and vary based on your company’s current status and your earned income, so you can’t know exactly how much tax you’ll owe until you actually exercise.

But you should prepare for tax payments before exercising to avoid cash flow problems later. So definitely be aware that you have to pay taxes when exercising stock options.

Ready to sell that stock?

Even after exercising stock options to buy stock, it’s not your money yet. You need to sell your stock to actually realize the profit.

So who do you sell these shares to? If your company is publicly traded, selling stock is easy. But most stock options are granted when companies are still small and growing, so even when your vesting plan ends and you actually buy the stock, the company is often still private.

When trading unlisted stock, you use OTC platforms like Seoul Exchange or Ustock Plus Unlisted, or you trade directly with a buyer through a contract.

But here’s an important point: stock received from stock options often has right of first refusal provisions, or might be completely locked from selling before IPO (initial public offering) or M&A (merger & acquisition).

Right of first refusal means the right to purchase shares before anyone else, and in most cases the holder of this right is the company (corporation) or someone designated by the company (individual).

The reason companies bother us like this is simple - whether it’s newly issued shares or treasury stock distributed, they’re wary of these shares ending up in hostile hands.

When you exercise stock options, existing investors’ equity gets diluted. By buying back these shares or redistributing them to existing investors, they’re trying to maintain friendly ownership.

So when you transfer stock acquired from exercising stock options, read the original grant agreement carefully and check whether you need to give written notice to the company, whether there’s a right of first refusal holder, and whether you can actually sell the stock.

Sold your stock? Time to pay taxes!

So once you’ve sold all your stock, are you done? Nope. You also have to pay taxes on the profits from selling the stock. In the US, you don’t pay separate taxes at exercise - you just pay 20% capital gains tax when you sell the stock. But in Korea, you pay income tax when exercising stock options AND income tax again when selling the stock. (Stop taking my money!)

This tax is called capital gains tax, which will be familiar to anyone who trades foreign stocks. You have to pay 22% capital gains tax annually on profits from foreign stock trading.

So many people think there are no taxes beyond securities transaction tax when trading domestic stocks. But this depends on whether the stock you’re selling is from a listed company or an unlisted company.

If you’re selling stock when your company is still unlisted and is a small to medium enterprise, you pay 11% total capital gains tax (including local income tax) on profits from selling the stock. If it’s a mid-sized or larger company, you pay 22%. (Local income tax is 10% of the tax owed)

| Company size | Capital gains tax rate (including local tax) |

|---|---|

| Small to medium enterprise | 11% |

| Mid-sized/large enterprise | 22% |

If your ownership is 4% or more or your shares are worth over 1 billion won, you’re classified as a major shareholder and pay more capital gains tax. But since we’re rarely major shareholders, just think of it as 11% or 22% including local income tax.

The silver lining is that there’s a 2.5 million won capital gains tax exemption. So if your total profit from selling stock is 10 million won, you only pay 11% tax on 7.5 million won (after deducting the 2.5 million won exemption). But since stock option profits are usually at least in the tens of millions, it’s easier to just assume you’ll pay capital gains tax from the start.

If your company is publicly traded, as long as you’re not a major shareholder, you won’t pay capital gains tax - it’s just like regular stock trading.

Stock option expiration

This is another thing many people miss - even vested stock options don’t give you rights that last forever. In other words, under certain conditions your stock option grant can be cancelled or you might lose the ability to exercise.

Stock option expiration terms vary by company, but here are some common cases:

- Quit your job? Stock option grant cancelled

- Quit your job? You must exercise all vested stock options at the time you leave

- You must exercise within 4 years of being granted stock options

This is also in the stock option grant agreement, so read the agreement very carefully when receiving stock options.

How can you make a good choice?

So when faced with choices like “stock options vs. salary increase,” what should you consider? Personally, I’d recommend looking not just at the stock option amount, but also at things like the vesting plan and tax optimization benefits.

Calculate actual profit from stock options

If you’ve read this far, you know that receiving 100 million won worth of stock options doesn’t mean your actual profit will be 100 million won.

When exercising stock options, you have to pay the strike price to the company and also pay income tax. When selling stock acquired from stock options, you pay capital gains tax again. Of course, we’re not tax accountants, so we can’t predict future taxes precisely. But you can roughly estimate how much you’ll owe based on tax rate information already available online.

Depending on acquisition value, you might pay up to 45% of your profits in taxes, so definitely calculate and recalculate before choosing stock options.

You must stay at the company until the cliff

As I mentioned, Korean law requires at least 2 years of employment before you can vest stock options. But depending on the company’s vesting plan, the cliff might be 2 years or 3 years, so think of cliff === period I can’t quit the company when making your decision.

You need to pass at least the cliff period before you have any exercisable stock options. So if you don’t plan to stick around that long, it might be better to just take cash like a signing bonus and invest it separately.

Consider company size and growth potential

Stock options are financial instruments that benefit you more when your company grows and the gap between strike price and market price widens. In other words, your potential gain depends on “how much more this company will grow.”

For example, a startup that just finished Series A funding has such a low current valuation that it’s common for valuations to increase 20x or 30x with each funding round. Well-performing companies sometimes get valuations over 100x higher.

That’s why you hear about stock option jackpot stories in the tens of millions - they mostly come from this space. But the flip side is these companies might not have found product-market fit yet and have no market influence, so there’s also a high probability your stock options become worthless.

But if your company has already grown to Series D or E funding rounds, the chance of the company failing and your stock options becoming worthless is low - but growth potential might not be as huge as a tiny startup.

Plus, large companies like Naver or Kakao don’t qualify for venture exemptions. So even if you get stock options now, you’ll barely get any tax benefits, and the stock option strike price will be set at market value at grant time, so when you run the numbers it might not be such a huge amount.

Of course, even if the company is large, if they’re planning promising new business ventures that could skyrocket the company’s value, the stock options could be almost as safe as guaranteed assets. So before accepting stock options, try to gather as much information as possible about the company’s future plans to make a good decision.

Plan your personal cash flow

When explaining stock options earlier, I talked a lot about cash flow. People usually only think about corporate cash flow, but cash flow is extremely important for individuals too.

Once cash flow gets blocked, you might have to take out unplanned loans or sell stocks at a loss just to raise cash.

If you haven’t thought about or planned for the strike price and taxes you’ll need to pay when exercising stock options, you might not be able to exercise when the time comes due to lack of funds, or you might have to take out loans to pay taxes - a truly tearful situation.

So before choosing stock options, ask about the company’s vesting plan ahead of time and think about whether you’ll have major expenses like lease renewal when your cliff hits and vesting periods come around.

Closing thoughts

As I mentioned at the start, I wrote this post because many people holding stock options simply think of them as regular stock.

Especially for people receiving stock options for the first time, when I tell them “that’s not free, you have to pay money when you exercise,” they sometimes ask why they have to pay money to sell stock - showing how many people really don’t understand stock options. (Surprisingly many people thought vesting stock options meant selling stock)

But stock options are financial instruments paid as compensation, so it’s very important to know exactly how much compensation you’re receiving and what process you need to go through to realize that compensation as profit.

Also, many people think stock options are granted for free, but by choosing stock options you might be accepting a lower salary increase rate or even freezing your salary, and you might be giving up cash benefits like signing bonuses. So it’s not really free.

The salary increase or cash benefits you’re giving up become an opportunity cost, and this opportunity cost is effectively the premium you’re paying to receive stock options as a financial instrument.

I hope that going forward, when you encounter choices like ”50K in stock options,” you’ll consider all these factors and make decisions that maximize your potential gains.

That wraps up my post on everything developers need to know about stock options.