Why You Can't Parse HTML with Regex

Backtracking and Automata: Why Regular Expressions Can't Understand HTML

This post is the third installment in my series about regular expressions, that dreaded beast whose name alone is enough to make you break a sweat.

As everyone knows, regex is infamous for its gnarly syntax, and there’s no shortage of posts out there (like my own Finding Patterns in Irregularity) that break down regex grammar and usage.

On the flip side, once you get comfortable with that gnarly syntax, you can solve a surprisingly wide range of string problems with short regex patterns. This is why regex occupies a love-hate place in most developers’ hearts. (Most developers I know aren’t exactly fans of regex either…)

So when solving problems with regex, many of us either copy-paste patterns found via Google or hack away on sites like regexr, and in the process, it’s not uncommon to use a flawed regex without proper validation and pay the price.

Of course, looking at a regex and determining whether it’s correct isn’t easy. But if you understand why regular expressions were created in the first place and what kind of environment they were designed to run in, the limitations of regex become naturally apparent.

In this post, I’ll explore the purpose and limitations of regular expressions through a single question that’s especially familiar to frontend developers like me: can you parse HTML using only regex?

When Bad Regex Causes Late Nights at the Office

Before diving in, let’s look at what can happen when a poorly written regex makes it into your code.

The kind of “poorly written” regex I’m talking about here isn’t the “the regex was supposed to find a but found b” variety. That kind of mistake is just unfamiliarity with regex syntax — spend a bit more time studying the pattern and anyone can spot the error.

What I’m talking about are performance issues that arise from not understanding how regex works internally, or the sad situation of spending hours trying to solve a problem that regex fundamentally cannot solve.

Of course, the regex engine exists as an abstraction layer so developers can use regex without understanding these internals. But trusting the engine too blindly can absolutely come back to bite you.

The Regex That Never Ends

The first kind of bite is a performance issue that can occur when you don’t understand how regex matches patterns.

Regex uses a backtracking algorithm based on DFS (depth-first search) to match string patterns. This means that depending on which nodes are explored and under what conditions, the matching time can become surprisingly long.

In particular, the regex engine built into JavaScript engines operates synchronously, not asynchronously. So if a regex takes a long time to match, nothing else can execute during that time: a truly painful scenario.

If that’s hard to picture, open a new browser tab and try running this in the console. (Do it in another tab so you can still read this post…)

// Always exactly 8 explorations regardless of string length

/^(\d+)*$/.test('123123123123123123');// 26 explorations

// This finishes quickly

/^(\d+)*$/.test('123!');

// 98,306 explorations

/^(\d+)*$/.test('123123123123123!');

// Uh... the computation never ends....

/^(\d+)*$/.test('123123123123123123123123123123123123123123!');The first example always completes in just 8 explorations regardless of string length. But in the second example, adding a single special character to the end causes the number of operations to grow exponentially, eventually reaching the point where it never finishes.

If this happened in an actual business application, the user would be staring at a frozen screen, unable to interact with any UI element. There’s even an attack method called ReDoS that exploits exactly this behavior to bring systems to a halt.

This is the kind of late-night debugging session you might find yourself in when you don’t understand how regex works under the hood.

What makes it even more frustrating is that these regex patterns don’t throw errors; they just take exponentially longer to execute. That makes it even easier to get blindsided. And even if you do track it down, these kinds of bugs are notoriously hard to find. (And even if you do find it, realizing the culprit is a regex is its own kind of despair…)

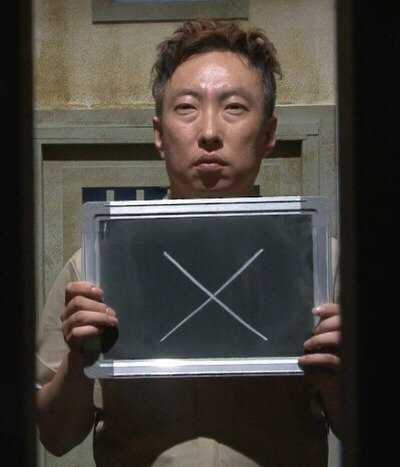

The face you make when you realize your overtime was caused by a single bad regex.

The face you make when you realize your overtime was caused by a single bad regex.

Because of how the backtracking algorithm works, the exploration path can dramatically impact performance. So when using regex, you should always keep in mind that unexpected situations like this can occur.

Problems Regex Simply Cannot Solve

The second kind of bite is trying to solve a problem with regex that regex fundamentally cannot solve.

The first situation can at least be detected through performance monitoring: “something’s off with this regex.” But this second situation? If you don’t understand the principles and limitations of regex, you could spend an entire week going in circles. Personally, I find this second scenario the sadder one.

As I’ll explain below, regex is not some master key that can find patterns in any string. It’s actually a tool with strict limitations.

Most notably, languages with arbitrarily nested tags or brackets — like HTML and CSS — cannot be validated with regex. So the answer to this post’s title question, “Can you parse HTML with regex?” is:

.

.

"No."

"No."

If you didn’t know that parsing HTML with regex alone is impossible, you could end up wasting a lot of time trying to solve a literally unsolvable problem.

But wait — many of us, myself included, have used regex to work with HTML before. So why am I saying it can’t be done?

The key distinction is that what we were actually doing was checking small, constrained rules like “did a <div> tag open and close?”, not validating an entire HTML document.

To understand why full HTML validation is impossible with regex, we need to look at the context in which regex was developed, the assumptions it was built on, and the limitations that follow.

Why Were Regular Expressions Created?

The term “regular expression” is already familiar to developers — so familiar, in fact, that it’s spawned various nicknames and memes in developer communities around the world.

But few people stop to wonder why it has this peculiar name: “regular expression.” So as a first step toward understanding what regex actually does, let’s think about what this name means.

The English word “regular” means something that follows a rule or pattern. A “regular expression” is literally an expression that represents a regular pattern. That’s why we generally think of regex as a tool for matching patterns in strings.

The word “pattern” here doesn’t just mean simple repetition like 12121212. It encompasses any rule a user defines, such as ”a appears twice, followed immediately by b.”

So the most basic use of regex is finding patterns in strings. But regex wasn’t actually created just to satisfy the need for string pattern matching. So what kind of pattern is a regular expression actually expressing?

Expressing Languages That Machines Can Understand

As mentioned, regex was born to express patterns. But to truly understand its origins, what matters more is understanding why people wanted to find patterns in strings in the first place.

The short answer: regular expressions originated from the effort to express languages that machines can understand. In other words, regex was born as a concept for mathematically expressing language so that machines could recognize it.

Of course, “languages that machines can understand” at the time didn’t mean high-level natural languages like the ones we research today.

Here, “language” doesn’t mean natural languages like English or Korean. It’s a more abstract concept. Just as we call programming languages “languages,” in computer science and mathematics, a language simply means a set of strings that follow certain rules.

The Mathematical Definition of Language

We all have an intuitive sense of what a “language” is, but most of us have never rigorously defined it.

In computer science and mathematics, however, intuitive knowledge doesn’t cut it. If you want to use the concept of “language” in these fields, you need a precise definition.

A language, in the mathematical and computer science sense, is simply a set of strings — nothing more, nothing less.

But it’s not just any arbitrary collection of strings. The set of strings that constitutes a language must satisfy three conditions:

There must exist a finite set of symbols S

There must be rules for forming S*, a set of strings made from elements of S

It must be possible to determine what meaning each string in the set carries

Any set of strings satisfying these three conditions qualifies as a basic language. Now that we know the definition, let’s satisfy each condition one by one and build a language.

First, what does the set of symbols S mean?

If you think about it, every language on Earth has symbols used within that language. Korean has consonant symbols like ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄷ and vowel symbols like ㅏ, ㅑ, ㅓ. English has symbols like a, b, c. We call these collections of symbols an “alphabet,” and this alphabet is the set of symbols S — the first condition of a language.

Let me define an alphabet. I’ll keep it simple with just two symbols: a and b.

S = ['a', 'b']Now I’ve fulfilled the first condition: “a finite set of symbols S.” Next, I need to create S*, the set of strings made from elements of S. The second condition says we need rules for forming this set.

These rules are what we call the syntax of the language. Since many languages share the same alphabet, it’s this second element — the syntax — that gives each language its character.

[Same Latin alphabet, different rules for combining strings]

English: I love you

French: je t'aime

Italian: ti amoAs you can see, English, French, and Italian largely share the Latin alphabet. Even for the same concept of “love,” English uses the 4-letter string love, while French uses l'amour with 7 characters including an apostrophe.

So defining just an alphabet isn’t enough to define a language. I’ll set the rule for my string set S* as “all strings of 3 characters or fewer that can be made from the alphabet a and b.” Then the set S* of my language looks like this:

S* = [

"",

"a", "b",

"aa", "ab", "ba", "bb",

"aaa", "aab", "aba", "abb",

"baa", "bab", "bba", "bbb",

]Now that I’ve defined the second condition, I can see exactly what strings my language contains. At this point, the third condition is automatically satisfied.

Since my rule — “all strings of 3 characters or fewer made from a and b” — produces only a finite number of strings, it’s possible to assign meaning to each one.

a = I'm hungry

b = I want to go home

aa = The server is returning 500s

...Just like that, I’ve satisfied all three conditions and created a humble language. I’ll call it “Evan-ese” going forward.

Machine, Please Understand My Language

Creating a language with simple rules isn’t hard — anyone can create something like Evan-ese. The question is whether a machine can understand it.

For a machine to understand a language, the strings that compose it need to have a recognizable pattern. If we can express the pattern of a language’s strings mathematically, then we can say this is a language a machine can understand.

Of course, natural languages like English or Korean have highly free-form context and evolving grammar, so absolute patterns don’t exist. But if the rules governing a language’s strings are clear — like Evan-ese — then it’s a language a machine can understand.

Evan-ese has a clear rule: strings of 3 characters or fewer made from a and b. This can be expressed as a mathematical formula:

Since Evan-ese consists of “strings of 3 characters or fewer made from a and b,” the empty string is also included. That’s why the formula adds (epsilon, representing the empty string) to each position, and the language Evan-ese includes as well.

And when you translate this formula into a specific notation that machines can understand, you get…

^[ab]{0,3}$…the regular expression we all know.

In other words, the first step toward making machines recognize language was to create a way to express the “rules” by which a language’s strings are generated. That’s the origin of regular expressions. If you look at the Wikipedia article on regular expressions, you can see this context reflected directly in the definition:

A regular expression […] is a sequence of characters that specifies a match pattern in text. Usually such patterns are used by string-searching algorithms for “find” or “find and replace” operations on strings, or for input validation.

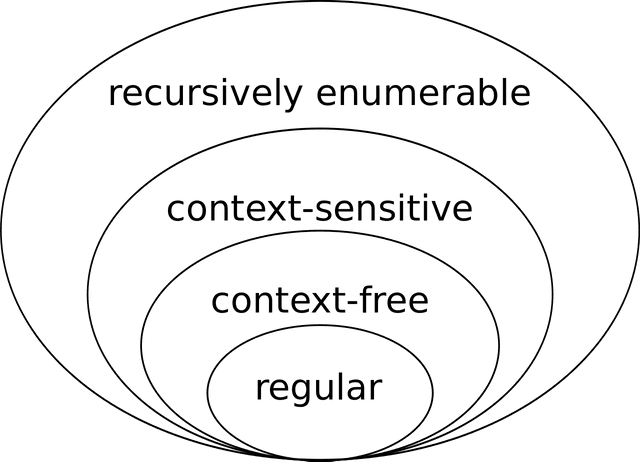

Of course, the definition of language I’ve presented here is quite simplified. If you’re interested in going deeper, I’d recommend searching for “formal language” and “Chomsky hierarchy.”

The Runtime Environment for Regex: Finite Automata

We now know that regular expressions weren’t simply born to match string patterns — they emerged from the effort to make machines recognize language. But I’ve been saying “machine” over and over. What machine exactly?

Regular expressions as a concept were born in 1951. Computers did exist at the time, but it was the wild days of debating whether to use mercury delay lines or magnetic cores for memory — not exactly an era where you could write code without worrying about memory constraints.

So research on machines during this period often involved imagining abstract machines in your head rather than working with actual computers. (The OG of vibe coding…)

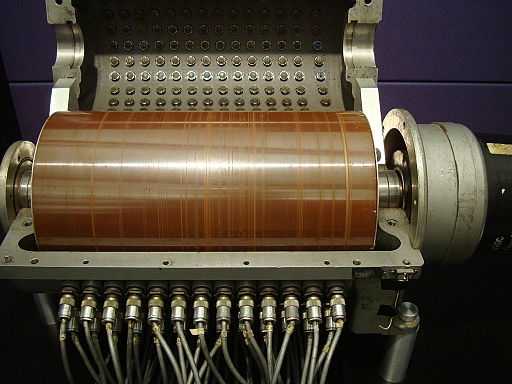

Behold the majesty of the magnetic drum — cutting-edge computer memory circa 1952

Behold the majesty of the magnetic drum — cutting-edge computer memory circa 1952

Among these abstract machines, regular expressions specifically emerged from research on making finite automata (abstract machines) understand language.

“Automata” means automatic (Auto) machine (Mata). Since these are abstract automated machines, they don’t require physical devices like computers. They can exist purely as theory or design.

The study of automata is fundamentally about finding answers to what a machine can and cannot do, making it a foundational field for the computer science we study today.

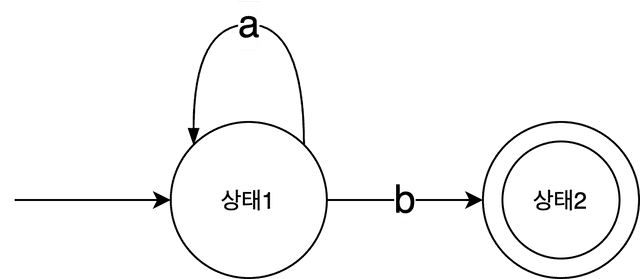

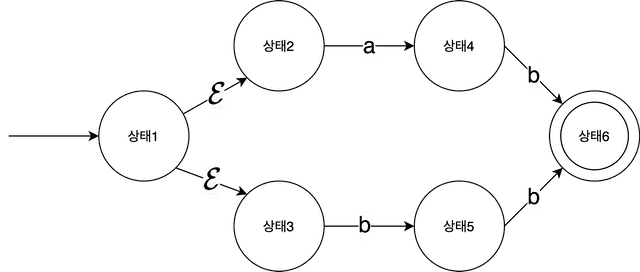

A finite automaton, in simple terms, is a machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any time. When designing finite automata, we use diagrams called state transition diagrams to illustrate how states change. They look something like this:

This state transition diagram shows how a finite automaton’s state changes. The machine receives a string as input: if the character is a, it transitions to State 1; if the next character is b, it transitions to State 2. State 2 is the machine’s final (accepting) state, shown as a double circle.

If this machine reaches its final state after processing an input string, the string is guaranteed to be something like ab, aab, aaa...b, and so on. This machine can also be expressed as the regex a+b. The machine I drew and the regex a+b are conceptually equivalent — the regex is just a representation of that machine. (Finite automata and regular expressions are said to be in an equivalence relation.)

When there’s only one possible path from any state to the next, you can tell at a glance how the machine will behave just from the state transition diagram. That’s because from any state, there’s exactly one possible next state. Such a finite automaton is called a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) because the state transitions are already fully determined.

DFAs are simple in structure and fully predictable, making them easy to implement as programs and efficient to run. But they have one drawback:

Expressing a language's structure with a DFA's restricted state transitions is really hard...

Expressing a language's structure with a DFA's restricted state transitions is really hard...

Why is it hard? For a simple regex like a+b, drawing the state transition diagram as a DFA is straightforward. But try expressing something like (a|b)b — which includes an OR — as a DFA, and it gets tough. A DFA requires that for any given input, there be exactly one possible next state. It’s like trying to handle conditionals without if statements.

For this reason, when expressing machines that recognize language, we use machines where multiple next states can exist rather than just one. Since the next state depends on the input, you can’t predict from the diagram alone how the machine will behave.

Such a machine is called a Nondeterministic Finite Automaton (NFA) because the state transitions aren’t predetermined but change depending on the input.

The machine above starts by accepting the empty string , then transitions to State 2 if the next character is a, or to State 3 if it’s b. There are two or more possible next states from a single state. Since you can’t tell from the diagram alone what the next state will be, it’s called “nondeterministic.”

This is the rough concept of finite automata — the machine that regex runs on. Regular expressions were designed with the goal of making this kind of abstract machine recognize language. The critical point to note here is that a finite automaton can only remember a single state at a time.

This constraint is precisely what creates the limitations of regular expressions as a language.

The Limitations of Regular Expressions

Languages that can be expressed by regular expressions — that is, languages that finite automata can understand — are called “regular languages.”

As we’ve seen, regex was originally designed to express languages with mathematically describable rules, and it was built to run on finite automata that can hold only one state at a time, so it cannot express all languages.

Think of it this way: you can’t express free-form natural languages like English or Korean with regex. (If you could express natural language with regex, we wouldn’t need machine learning.)

In other words, there are clear limits to what regex can express, and the languages within those limits are called regular languages.

Even among the strings we deal with in everyday business contexts, quite a few aren’t regular languages. The most prominent example is HTML. In other words, it’s impossible to determine whether a given string is valid HTML using regex.

Wait, I've definitely matched HTML with regex before though?

Wait, I've definitely matched HTML with regex before though?

Sure, I’ve matched HTML with regex too. But the rules we were applying at the time were small, constrained checks on parts of the HTML (like “did a <div> tag open and close?”), not validating the entire HTML document.

So why do I say regex can’t validate HTML? The answer becomes clear when you remember that regex represents a finite automaton that can only remember a single state, and then look at HTML’s structure.

Why Regex Can’t Understand HTML

As we all know, HTML has a structure where tags open and close, and tags can be nested infinitely deep inside other tags.

<main>

<section>

<h1>

...

</h1>

</section>

</main>So if a machine receives an HTML string as input and needs to verify that it’s valid, what would it need to do?

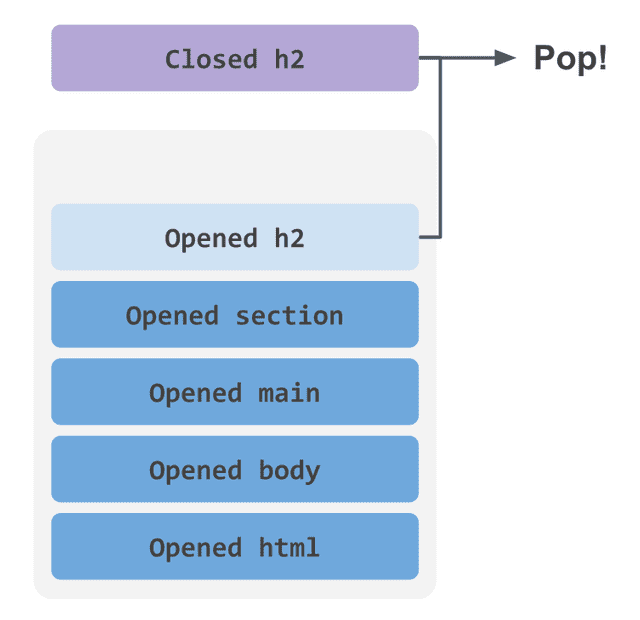

A valid HTML string requires every opening tag to have a matching closing tag, which means the machine needs to read characters one by one while simultaneously tracking which tags are open and closed. It would work roughly like this:

- Encounter

<main>. Store the state that the<main>tag is open. - Encounter

<section>. Store the state that the<section>tag is open. - …repeat

- Encounter

</main>. If the state says<main>is open, it has closed correctly. - Encounter

</section>. If the state says<section>is open, it has closed correctly. - If no tags remain open when the end of the string is reached, this is valid HTML.

If you were building such a machine, how many states would it need to store?

.

.

The answer is infinite.

If that’s not immediately clear, imagine building an HTML parser yourself. As discussed, this parser needs to verify that tags are properly opened and closed, so whenever it encounters an opening tag string, it needs to store that state somewhere.

The exact approach to state management may vary from person to person, but the classic technique for validating matched pairs of opening and closing brackets is using a stack.

No matter how deeply tags are nested, inner tags must always close before outer ones — and the stack’s last-in-first-out property is a perfect fit for validating this structure.

But the problem is the size of the stack. How large does the stack need to be to handle any possible HTML string?

The bigger the better, obviously. A larger stack means you can parse HTML with deeper nesting. But eventually, an HTML tree deeper than the stack’s capacity will come along and crash the program, which means that to build an HTML parser that can handle any string, the stack size needs to be infinite.

Regex Is Ultimately a Finite Automaton

Validating whether HTML is well-formed requires an infinite number of states. But regex represents a finite automaton that can hold only a single state, so it fundamentally cannot recognize HTML, which requires infinite states to parse.

The core takeaway is that regex represents a finite automaton that can only hold one state, and there exist problems that such a machine simply cannot solve.

So rather than reaching for regex the moment you see a string problem, it’s better to first think: “If I were building a parser for this string, how many states would I need?” If the answer is two or more, you can generally conclude that regex alone won’t cut it.

Of course, this kind of mental simulation differs between those who are experienced and those who aren’t; you might think a problem requires multiple states when one would suffice. But algorithms are a domain of practice, not talent, so with a year or two of steady effort, your intuition will sharpen over time.

Closing thoughts

The limitations of regex can actually be summarized in a single sentence: “it cannot recognize strings with unbounded nesting depth.”

But rather than just stating and memorizing that, I thought it would be easier to understand if we explored what problem regex was created to solve and what concept it’s built on.

If you don’t know that regex has these limitations, you might take your experience of using regex in constrained situations (like checking whether a <li> tag exists inside a <ul> tag) and try to tackle a fundamentally unsolvable problem.

Regex does provide a lot of convenience when working with strings, that’s true. But as we’ve discussed, the backtracking algorithm can introduce unexpected performance issues, and there are problems regex simply cannot solve. So before reaching for regex, it’s always worth asking: “Is this really the right tool for the job?”

That’s all for this post on why you can’t parse HTML with regex.