Why Good Developers Care About Business

Software engineering is more than code — it's understanding markets and people

In this post, I want to talk about a topic that’s both distant and close to developers: business. Developers are people who constantly agonize over good architecture and robust applications. But the best architectural choice isn’t always the right choice — because we’re hired to make money using programming.

When developers talk about “good design,” you’ll hear plenty about TDD, DDD, SOLID, open-for-extension architectures, pure functions, and other technical topics. But far fewer talk about business. When you consider that developers aren’t people who simply program, but people who do business through programming, that seems a bit odd.

We Are Employed

Some developers work as freelancers, but most of us — myself included — are employed by a company. So why does a company hire developers?

Obviously, to make money using your programming skills. As everyone knows, a company is fundamentally a profit-seeking organization, so the salary they pay you is an investment. If a company pays you $50,000 a year, they naturally expect you to generate at least that much — or more — in value.

In other words, a developer isn’t just someone who needs to be good at programming. A developer needs to be someone who can generate money through programming.

The reason companies hire developers is ultimately to generate revenue

The reason companies hire developers is ultimately to generate revenue

If we compare the IT industry to traditional manufacturing, developers and designers are the craftspeople who make things. The only difference is that what we produce has shifted from physical goods to software. And a craftsperson isn’t just responsible for product quality — they must simultaneously care about real user satisfaction, the company’s business requirements, and much more.

In other words, a profit-seeking organization doesn’t just need someone who’s good at programming. It needs someone who can use programming to satisfy users and generate the revenue that follows.

That’s why many organizations look for more than just programming skills when hiring good craftspeople. They also look for smooth collaboration with stakeholders, leadership, business insight, understanding of user experience, and various other skills needed for effective product development.

Moreover, things like collaboration skills and UX understanding may not generate immediate revenue, but in the long run they significantly impact the company’s brand and culture, and can ultimately transform how the organization works and performs. Serious organizations don’t neglect these factors.

In short, a developer isn’t just someone who programs — they’re one of many team members racing to make their organization’s product succeed in the market. That’s why developers shouldn’t focus solely on programming, but should develop a broad perspective that encompasses the organization’s business challenges as well.

Why Do Developers Pursue Good Design?

When you work as a developer, you can’t help wanting to invest the time for good architecture — it’s your baby, after all.

Developers know from experience that cutting corners on design today creates debt that boomerangs back eventually. The classic example is the “legacy code” meme that’s ubiquitous among developers.

Code with poor readability and unclear control flow harbors countless potential bugs. Sometimes bugs occur but slip past tracking tools due to weird exception handling. Poorly designed code can create major pain points for users, and in severe cases, ruin critical user moments and drive them away.

What’s worse, if you keep piling features on top of bad design without improving it, the bad design only grows. Development isn’t about wiping the slate clean for every new feature — it’s about building on top of what already exists.

Once design goes off the rails, even a small change can trigger bugs in unexpected places. Developers become increasingly cautious, and the organization’s development velocity gradually slows. Eventually, you might want to add a new feature but literally can’t because the architecture won’t allow it.

How I feel looking at code I wrote a year ago...

How I feel looking at code I wrote a year ago...

Ultimately, developers pursue good design to maintain high code quality, preserve development velocity, and prevent unpredictable bugs. But as I said earlier, a good craftsperson doesn’t just focus on programming — they need a broad perspective that encompasses business too. Developers are, after all, the people who build products and deliver them to users.

Reframing through a user-centric lens: the reason developers pursue good design is to maintain rapid development velocity so users consistently receive improved products quickly, and to prevent mysterious bugs from giving users bad experiences.

In other words, good design is for the sake of good user experience.

But think about it — good design isn’t the only thing developers can do for user experience. Good design is just one of many approaches to delivering great experiences. A good developer should be able to choose the option that delivers the maximum benefit at the minimum cost given the current situation.

We’re Not the Old Man Whittling a Bat

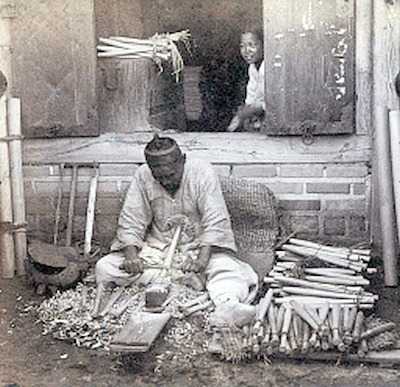

In Korean culture, there’s a well-known essay called “The Old Man Whittling a Bat” that’s often cited when discussing craftsmanship. It appears in middle school textbooks, so most Koreans have read it at least once.

The full story is quite long, but here’s the gist:

One day, a man passing through town tries to buy a laundry bat from an old craftsman carving them by the roadside. But the old man quotes a steep price…

Customer: “Could you give me a discount?”

Old man: “Haggling over one bat? Just go buy one somewhere else.”

Customer: “Fine, I’ll pay full price. Just make sure it’s well made.”

The customer watches the old man work, growing increasingly impatient. It looks done to him, but the old man keeps whittling. Time is running out…

Customer: “It looks finished. Can I just have it?”

Old man: “Rice has to boil until it’s done. Raw rice doesn’t become cooked just because you rush it.”

Customer: “The buyer says it’s fine! I’m going to miss my bus…”

Old man: “Then go buy one somewhere else.”

Customer: “Sigh… fine, take your time.”

Old man: “The more you rush me, the longer it takes. Just wait.”

The customer misses his bus and his mood is ruined. The old man doesn’t care about customers at all — no wonder his business is struggling.

…But later, upon closer inspection, the quality of the bat turns out to be extraordinary.

The story ends with the protagonist wanting to go back and apologize to the old man for failing to appreciate his deeper purpose.

The moral, in a word, is “respect for craftsmanship,” and it’s frequently cited as an example of the mindset makers should have.

The old man in the story takes immense pride in his whittling skills. He’s probably been doing this for a long time, which means he has clear convictions about his craft. Developers who’ve been in the industry for a long time aren’t much different in that regard.

But there’s one crucial difference between this heartwarming story and reality. The old man never intended to sell to anyone who didn’t share his values. That’s essentially the same as a developer telling users, “I need to take my time and build a proper architecture, so if you don’t like it, use a different app” — while users are complaining, “Why is this app so slow to update?”

Viewed this way, the old man doesn’t seem so professional after all. Wouldn’t a true professional find a way to deliver the best possible quality within the timeframe the customer needs — satisfying both the customer and themselves?

The protagonist in the story watches the old man work and thinks, “It looks done — why does he keep going?” If the old man represents the developer, then the protagonist represents the users.

And unlike this patient protagonist, real users won’t wait around the moment they think “something’s off.” They won’t marvel at the quality of your carefully designed product either. The moment users sense something is wrong, they’ll abandon your product and switch to another.

Finding the Balance Between Business and Good Design

As I’ve discussed, developers need to consider business factors while simultaneously thinking about good application architecture. But many developers invest heavily in studying technical approaches to good design while giving surprisingly little thought to business.

The developer community’s idea of a “good developer” often centers on someone who’s great at programming, or at most, someone who can uplift other developers. So we study paradigms like functional programming, various design patterns and guidelines, and work hard to apply them in practice.

But in my view, one of the conditions for being a truly effective developer is having all of that plus business insight. And beyond that, having a range of soft skills too. As I’ve said multiple times, a developer isn’t someone who sits isolated with a computer doing nothing but programming.

The “good design” I’m really talking about isn’t simply abstracting duplicate logic or using extensible patterns. Depending on the situation, copy-pasting existing code might be good design. In an urgent situation, shipping something that barely works — design be damned — might be good design.

Is This Really Worth Designing Well?

When designing an application, the first question you should ask is “Is this really worth investing in design?” Once you determine it is, that’s when you start thinking seriously about proper architecture.

Solid application design generally pays off in the long term rather than the short term. If the time you invest in design is more likely to not pay off in the future, then it might be better to just rough it out and ship the feature fast. Business is always about Cost vs. Benefit.

You might wonder what costs are involved in just “thinking about design,” but they’re real. Your salaries, server costs, office rent — money flows out of the company’s bank account every single day, even when nothing is happening.

Labor costs in particular are something many people overlook, and they add up surprisingly fast. Go ahead and calculate “my daily pay × team size” right now. A team of just 5 people each earning 1,000 per day.

If building one feature takes 5 days, the company spends roughly “$5,000 + α” on development costs. The “plus alpha” includes office rent, server costs, and so on.

And if deploying that feature actually decreases a critical conversion rate, the losses grow even bigger. That’s the risk a company takes when developing a product. Plus, if you’re running an A/B test, the feature you’re building right now might be deleted within a week.

In situations like these, always spending time on design isn’t necessarily the right answer. We need to ask “is this really worth designing well?” before asking “how should I design this?”

When Speed Matters More Than Solid Design

In practice, every developer encounters situations where they need to build something fast. The reason might be a client’s demand, a fresh startup that needs to find market fit quickly, or a company that’s genuinely running out of money — but what matters isn’t the reason, it’s that the product needs to ship fast.

In these situations, developers face a dilemma: invest time in solid design, or build something rough and ship it immediately.

Of course, as your skills grow, you develop an intuition (forged through years of trial and error) that raises the quality floor even when you’re cutting corners. But less experienced developers might produce genuinely hard-to-follow code.

As I mentioned, developers can clearly see the parts that will become tech debt if not designed properly now. From a long-term perspective, if design keeps getting neglected, the application’s complexity grows exponentially, and eventually you can’t add features even when you want to.

Having thought this far, the developer makes a decision:

"Right, I can't just give up on design. I need to negotiate the timeline...!"

"Right, I can't just give up on design. I need to negotiate the timeline...!"

Of course, thinking this way is entirely natural for a developer. But what matters is accurately understanding what the current situation actually is.

If the tight deadline is simply because the PO or client is impatient, there’s certainly room to negotiate. But if there’s a pressing business issue — like an imminent funding round that requires finding market fit fast and painting a pretty revenue graph — then negotiating for more design time isn’t such a great call.

No matter how thoughtfully a developer designs for the future, if the company runs out of money and shuts down next month, that code disappears anyway. As long as a developer works within a company, the lifespan of everything they produce ultimately depends on the company’s bank balance.

That’s why, even though programming is a developer’s primary job, they shouldn’t think only about programming. They should always view the feature they’re building through a business lens. Sometimes the right call is to cut corners on design, ship the product quickly, test it, find market fit, create user happy moments, and focus on increasing AMPU (Average Margin Per User).

In such situations, it might be better to accept some design compromises and develop quickly, while predicting risks from the compromised design, handling errors that could interfere with critical user actions, and deploying error monitoring solutions like Sentry or Bugsnag with aggressive Slack notifications to catch anything you missed. (Bug fixes, of course, you’ll just have to grind through.)

Sometimes You Build Features Meant to Be Deleted

And sometimes you have to build features that are meant to be deleted. What does that mean? New features are supposed to upgrade the product for users — how can a feature be “meant to be deleted”?

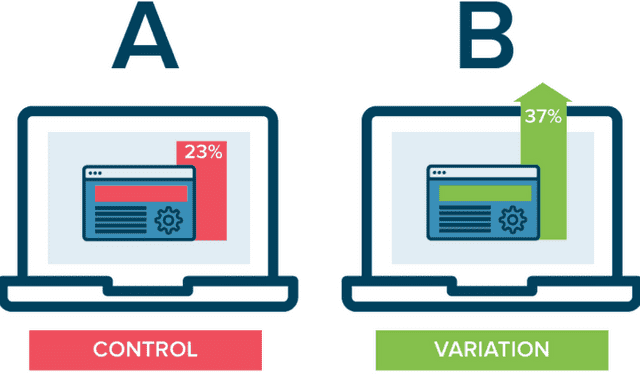

It happens when you need to run A/B tests.

A/B testing deploys both existing and new UI/UX to a test group,

A/B testing deploys both existing and new UI/UX to a test group,compares metrics, and keeps the winner.

For example, imagine your product’s payment page has a 10% conversion rate. To boost it, you make the payment button bigger and bolder, adding a striking #ff0000 color. This wasn’t a random decision — it was made after intense discussion and deliberation involving the PO, UI/UX designers, and the entire team.

So now that we’ve made the payment button more eye-catching after all that deliberation, will the conversion rate go up?

.

.

Nobody knows

Nobody knows

The truth is, nobody knows how users will react when you build a feature and release it. Users are unpredictable creatures who might suddenly bounce just because a single line of copy changed on a page. But you can’t just build random things and ship them either — the financial risks of labor costs, server costs, and more are too high.

That’s why many organizations use A/B testing to reduce this risk. No matter how brilliant the people gathered in a room, no matter how long they discuss and deliberate, at the end of the day it’s all just predicting “our users will behave this way.”

In other words, until you deploy and actually observe how users interact with your product, every opinion is just speculation — which is why you run these tests.

If the Control (existing version) shows higher conversion after the test, you simply discard the new Variant. If the Variant wins, you discard the Control. Either way, you safely improve conversion rates with minimal risk, regardless of whether your hypothesis was right.

For effective data analysis, you also need to control variables as much as possible. If you change a bunch of things at once and the metrics improve, but you can’t tell which specific change drove the user behavior, the test becomes meaningless.

That’s why A/B tests usually keep most features identical and only make small, focused changes to the part being tested. This means that when coding for an A/B test, there will inevitably be a lot of shared logic between Control and Variant.

Some developers abstract these common parts for an efficient design. But here’s the trap:

One of the two will eventually have to be deleted.

If you aggressively abstract shared code or split things into separate modules to reduce duplication, you actually increase the number of things to worry about when it’s time to remove the test code — and mistakes during removal can introduce unexpected bugs.

Moreover, A/B tests often have nearly identical variations down to trivial details. No matter how carefully you abstract, once the test ends and you delete one side, you may be left with pointless abstractions.

That’s why A/B test code should be built to be as easy to delete as possible. The code you write for a test isn’t something you’ll maintain long-term — it’s something that gets deleted after a week-long test at most.

You might say “just revert the commit since we have Git,” but that only works when the Control wins. If the new Variant wins, a revert is useless.

In cases like this, forget abstraction — just copy the entire page, route to /test-page/a or /test-page/b based on the A/B test variable, and when results come in, cleanly delete the losing page. That might actually be the better design.

If you develop with a narrow, programming-only perspective without considering these business realities, you might end up doing perfectly solid design work only to receive “overengineering” feedback — which is a truly sad outcome.

Wrapping Up

In this post, I’ve talked about the relationship between business and application design. Honestly, more experienced developers probably already know all of this.

But for developers who are just starting out, it’s common for their overflowing enthusiasm to be channeled entirely into programming-related work — refactoring architecture, adopting new and efficient technologies. When I first started as a developer, I was the same way. I said we needed to refactor all the legacy code without considering any business context, and received feedback to broaden my perspective. (Embarrassingly, at the time I thought the person giving that feedback was just being stubborn…)

Of course, as a developer myself, I get excited about open-for-extension architectures, clearly separated modules, and side-effect-free functions. But at the end of the day, I’m employed by a company, entangled with countless stakeholders and users who use my product. Realistically, it’s hard to do only what I want without considering any of that.

Just as developers value good design and paying off tech debt, designers value UI/UX, and CEOs value management. And most crucially, users only care about the experience they have while using the service.

Because everyone prioritizes different values, I wanted to use this post to say that developers shouldn’t have a narrow perspective focused solely on the application.

That’s all for this post on why good developers care about business.