RESTful APIs: Where Frontend Meets Backend

Understanding the philosophy of REST — between representation and action

In this post, I want to talk about APIs — the meeting point between frontend and backend developers.

When building applications that run on the web or mobile, we typically use HTTP or HTTPS protocols to create APIs. How intuitive and clear these API definitions are can dramatically reduce a project’s complexity, making API design a crucial part of system architecture.

That’s why we need conventions to clearly define what each API does, and the tools we use in this process are “HTTP methods” and “URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers).”

GET https://evan.com/users/1An HTTP API endpoint uses HTTP methods and URIs like the above to express what the API does.

The key point here is that what a user expects the API to do after reading this expression must clearly match what the server actually does. Imagine asking the server “take one step forward!” and getting the response “okay, I took one step backward!” — that would be pretty confusing, wouldn’t it?

Whether between humans or computers, poor expression leads to miscommunication

Whether between humans or computers, poor expression leads to miscommunication

That’s why we use guidelines like REST. REST is an API architecture guideline introduced by Roy Fielding in his doctoral dissertation back in 2000, and it remains widely used even after more than 20 years.

But as I discussed in my previous post on HTTP status codes, these are just guidelines — not following them won’t cause errors or break anything. That said, ignoring these guidelines and developing however you please isn’t a great idea either. The term and concept of REST is so widespread in the industry that most developers assume any HTTP API they encounter will be RESTful. (Its influence is practically on par with a de facto standard.)

For that reason, in this post I want to explore why REST came about in the first place, and what it actually means when people keep saying “RESTful this, RESTful that.”

What Does REST Actually Mean?

REST stands for REpresentational State Transfer. The heart of this impressive-sounding term is “Representational State” — which roughly translates to “a represented state.” The “state” here refers to the state of resources that the server holds.

In other words, REST is an architectural guideline about exchanging the represented state of resources through communication.

When discussing REST, many people struggle with understanding “representational state” because they think what client and server exchange through API communication is the resource itself.

But with a little thought, you can see that we’re not actually exchanging resources directly through communication.

What We Exchange Isn’t Actually the Resource

The resources we exchange through APIs could be documents, images, or simple JSON data. But we’re not actually exchanging the resources directly. Let’s look at a simple example to understand what this means.

Imagine a client sends a request to an API endpoint that fetches a specific user’s information from the server:

GET https://iamserver.com/api/users/2

Host: iamserver.com

Accept: application/jsonThe client used this endpoint to request user #2’s resource. If the server processed the request successfully, the client would receive a response roughly like this:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 45

Content-Type: application/json

{

id: 2,

name: 'Evan',

org: 'Viva Republica',

}The response body contains user #2’s data. Normally, we’d describe this situation as “we fetched user #2’s data resource through the /api/users/2 endpoint.” I use this shorthand myself for convenience.

But… is that JSON data the server sent really the resource itself?

Nope. That's not user #2's resource!

Nope. That's not user #2's resource!

The JSON the server sent isn’t the original resource — it’s merely a representation of user #2’s data resource stored in the database. The server received the client’s request, looked up user #2’s information in the database, and represented it using the application/json format specified in the request header.

Think about it — the actual original resource the server accesses is just a row in a database or data written to a file. Sure, the server might store resources as JSON files in its local system, but the point is that the JSON the server sent is not the original resource.

The JSON the server sent is simply the current state of the original data resource stored in the database, represented in a particular format.

What “Represented State of a Resource” Means

As I mentioned, REST’s “Representational State” means the state of an original resource as represented in some format. The original resource exists as a row stored in a database, but since you can’t just hand that raw data to the client, the server reads the original resource and represents it in an appropriate format.

And the hints about this “appropriate format” are all there in the HTTP request and response headers.

GET https://iamserver.com/api/users/2

Host: iamserver.com

Accept: application/jsonIn our earlier example, the client requested user #2’s resource and included application/json as the value of the Accept header. The client was telling the server: “represent user #2’s state in JSON format.” If the client had sent application/xml instead and the server supported XML format representation, user #2’s resource would have come back represented in XML.

The server then uses response headers like Content-Type and Content-Language to tell the client how the resource is represented, and the client reads this information to parse the content according to each content type.

In other words, the client didn’t receive user #2’s resource. It received the current state of user #2’s resource, represented in JSON. This is what REST focuses on — enabling clients and servers to freely and clearly represent resources using content types, languages, and other mechanisms.

RESTful API

As I discussed, REST is ultimately an architectural style focused on how to clearly represent resources. But when using HTTP APIs, the represented state of a resource alone isn’t enough for clients to know exactly what will happen on the server when they call an API.

REST only talks about the represented state of resources — it says nothing about “actions.” But what clients actually want when using a server’s API is clearly some action — creating, deleting, or modifying resources.

That’s why RESTful APIs leverage HTTP methods and URIs alongside REST architecture to specify both the represented resource and the intended action. Here’s what each element expresses:

- How is the resource represented? — REST

- Which resource? — URI

- What action? — HTTP Method

With these elements clearly defined, a client can look at an endpoint like GET /users/2 and immediately infer “ah, this API fetches user #2’s information” — no lengthy documentation needed.

Since I’ve already covered REST (how resources are represented), let’s now look at URIs (which resource) and HTTP methods (what action).

Using URIs to Express Which Resource

A RESTful API’s URI indicates which resource the API deals with. For example, imagine an API that fetches the list of users in a service. The resource the client wants to access is “users,” and the URI should clearly represent that.

GET /usersHonestly, this URI is clear enough that even a random middle schooler could tell it’s related to users. But why do we express the user resource as users in plural form rather than user in singular?

Because the user resource isn’t one specific object. It’s the same logic as saying “I love cats” instead of “I love a cat” in English.

I don’t love one particular cat — I love cats as a species, and the word “cats” here encompasses an abstract resource that includes the stray rummaging through trash cans in front of your apartment, someone’s pampered cat on Instagram, and every random cat you pass on the street.

Now, let’s get one level more specific from this abstract “users” resource. The next level of specificity from the abstract “users” is “a specific user.”

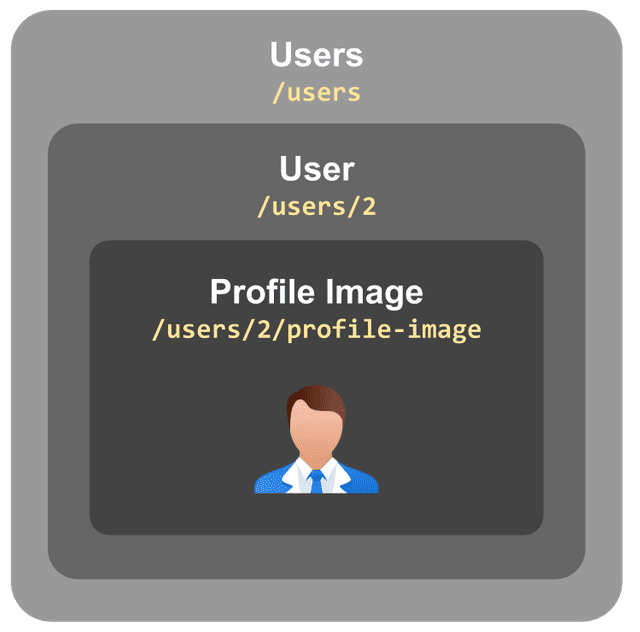

Expressing Resource Hierarchy

Since users typically have unique IDs, we can use those IDs to represent a specific user with a URI like this:

GET /users/2As you’ve probably noticed, this URI takes the /users URI that represents users in general and appends a unique ID to identify a specific user.

This “user #2” resource is a subset of the “users” resource, and RESTful APIs recommend using / to express hierarchical relationships between resources.

A hierarchy flowing from users > specific user > specific user's profile image

A hierarchy flowing from users > specific user > specific user's profile image

Resource hierarchy is an extremely important and sensitive element in API design because it’s about how you define relationships between your application’s resources. And like most design patterns, there’s no single right answer — you’re bound to wrestle with it.

Having no single right answer means that representing a profile image resource as /profile-images/users/2 instead of /users/2/profile-image is perfectly valid from a logical standpoint. The only difference is what meaning the profile image resource carries.

/users/2/profile-imageThe profile image of user #2 among users

/profile-images/users/2User #2's profile image among user profile images among all profile images

As you can see, the same profile image takes on completely different meanings depending on how you design the resource hierarchy. In this case, if no other resource besides users can have profile images, /users/2/profile-image makes sense. But if various resources need profile images, /profile-images/users/2 becomes worth considering.

Ultimately, the question we need to ask is: for the resource “a specific user’s profile image,” is “users” or “profile images” the more appropriate parent in the hierarchy?

As I said, there’s no right answer — so always discuss with your team and design URIs that can flexibly adapt to rapidly changing business requirements.

URIs Should Not Express Actions

Another important rule when designing RESTful API URIs is that URIs should never include expressions that imply an action. For example, imagine an endpoint that deletes a user. If you’re not familiar with HTTP methods, you might design something like this:

POST /users/2/deleteThis URI includes delete, which implies a deletion action. Sure, you can still tell what this API does, but RESTful API guidelines recommend against expressing actions in URIs. A URI’s meaning should be strictly about which resource and the resource’s hierarchical structure — nothing more.

Actions should be expressed using the appropriate HTTP methods. This isn’t just because RESTful API guidelines say so — it’s also because you never know what side effects might occur when your application (built without following RESTful guidelines) communicates with other applications that do follow them. (Web browsers alone are heavily designed around HTTP methods and status codes.)

So the properly designed endpoint would use the DELETE HTTP method, which represents deletion:

DELETE /users/2Now that we’ve covered how to represent resources using URIs, let’s look at how to express API actions.

Using HTTP Methods to Express Actions

RESTful APIs recommend using HTTP methods to express the actions an API performs. HTTP methods are a standard defined in RFC-2616, so remember that using a method that doesn’t match the situation can cause your application to behave unexpectedly.

In practice, most API actions boil down to “CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete),” so aside from a few special cases, just 5 HTTP methods can define the vast majority of APIs:

| Method | Meaning |

|---|---|

| GET | Read a resource |

| PUT | Replace a resource |

| DELETE | Delete a resource |

| POST | Create a resource |

| PATCH | Partially modify a resource |

Methods like HEAD, OPTIONS, and TRACE also exist, but knowing just these five and their roles is more than enough for expressing correct actions and designing RESTful APIs.

One potentially confusing pair here is PUT and PATCH. Both are often interpreted as “modify a resource,” making it hard to know when to use which.

What’s the Difference Between PUT and PATCH?

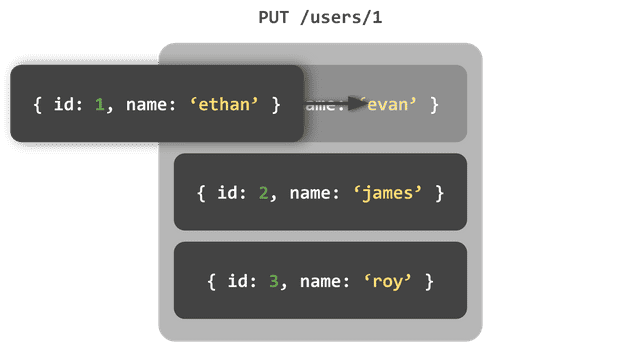

People commonly describe PUT as “modifying a resource,” but what PUT actually means is replacing a resource with whatever is in the request body — not modifying it.

Let’s say we need to change the name of a user resource { id: 1, name: 'evan' } to ethan. If we use PUT, we must include the entire user resource in the request body.

In other words, we have to send not just the changed fields, but the unchanged ones too.

PUT /users/1

{ id: 1, name: 'ethan' } PUT doesn't modify a resource — it replaces it

PUT doesn't modify a resource — it replaces it

Because PUT replaces the entire resource, if you accidentally send something like { id: null, name: 'ethan' }, this user permanently loses their ID — a tragic fate. (Admittedly, most developers handle this edge case.)

On the flip side, the simplicity of “just receive a resource and replace it” means neither the sender nor the receiver has to think too hard about it — which is convenient.

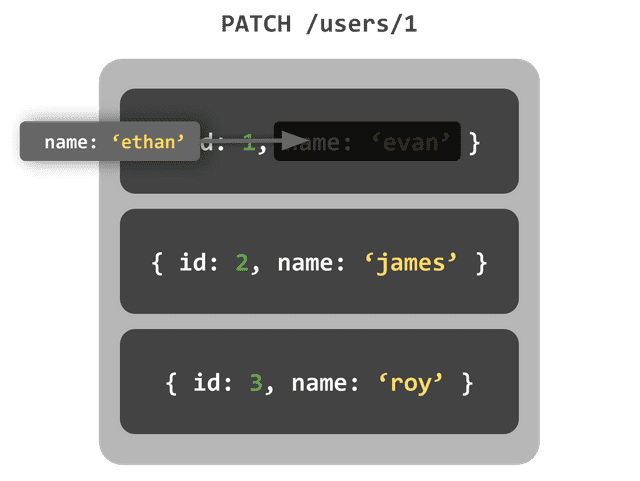

Now, what if we used PATCH for the same operation?

PATCH /users/1

{ name: 'ethan' } PATCH modifies part of a resource

PATCH modifies part of a resource

Unlike PUT, PATCH truly means modifying the currently stored resource, so there’s no need to include unchanged fields in the request body.

Since PATCH only requires sending what you actually want to change — unlike PUT which demands the full resource — you avoid unnecessarily large request bodies.

In practice, when performing update operations through APIs, people often think of it as equivalent to SQL’s UPDATE. In that sense, PATCH (which modifies part of a resource) is arguably a better semantic fit for “updating” than PUT (which replaces the entire resource).

While PUT is still more commonly used for update operations, the semantic difference between PUT and PATCH clearly exists, so I recommend choosing the method that matches your intended action — “replace a resource” or “modify a resource” — when designing endpoints.

However, the truly important difference between PUT and PATCH isn’t the semantic distinction — it’s that PUT always guarantees idempotency while PATCH may not.

Does the Method Guarantee Idempotency?

Idempotency, in mathematics and computer science, is the property that applying the same operation multiple times to a subject produces the same result. This isn’t specific to HTTP methods — it applies to all computer operations including reading and writing to databases or files.

The most classic example of an idempotent operation is multiplying a number by 1. A function like x => x * 1 returns x whether you apply it once or 10,000 times.

But a function that adds or subtracts 1 instead of multiplying would increase or decrease the given value with each call, so it doesn’t always return the same result. This is the textbook example of a non-idempotent operation.

Since HTTP methods represent CRUD operations on resources, understanding which operations are idempotent helps prevent applications from behaving unexpectedly. An error from calling GET multiple times and an error from calling POST multiple times can have completely different contexts.

| Method | Idempotent |

|---|---|

| GET | Yes |

| PUT | Yes |

| DELETE | Yes |

| POST | No |

| PATCH | No |

Let’s look at this table without overthinking it. GET simply reads a resource, so no matter how many times you call it, the result won’t change. Similarly, PUT replaces an existing resource with whatever is in the request — as long as the request body doesn’t change, the result stays the same no matter how many times you call it.

In other words, operations that read or replace resources are idempotent. So what about non-idempotent cases?

POST creates a new resource, so calling it multiple times creates a new resource each time — meaning the result of the operation changes with every call. Non-idempotent operations like POST can change the application’s state in completely different ways with each invocation.

Knowledge of HTTP method idempotency is also useful when debugging with limited error information. Even though both errors occur after network communication, an error from calling GET multiple times and an error from calling POST multiple times may have entirely different contexts.

Why Is PATCH Considered Non-Idempotent?

In the table above, PATCH is marked as non-idempotent just like POST. But to be precise, PATCH can be idempotent like PUT or non-idempotent — depending on how it’s implemented.

Since PATCH doesn’t replace a resource like PUT, there are no strict constraints on how the request should be structured. Per the RFC spec, PATCH simply means “modify part of a resource” — nothing more.

For example, when you use PATCH the way I described earlier — sending only the fields you want to modify — it’s naturally idempotent:

// Original resource

{

id: 1,

name: 'evan',

age: 30,

}PATCH users/1

{ age: 31 }// Updated resource

{

id: 1,

name: 'evan',

age: 31, // Changed!

}This PATCH request clearly means “set the age field to 31,” so no matter how many times you call it, age will always be 31. This is a very common implementation of PATCH, and it’s how I personally implement it too.

So why do people say PATCH might not be idempotent?

The nagging suspicion that maybe this isn't the only way to implement PATCH

The nagging suspicion that maybe this isn't the only way to implement PATCH

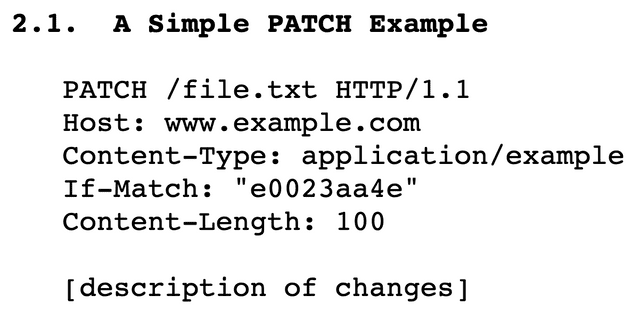

Origins matter, so let’s crack open RFC-5789 — the document that first defined the PATCH method. RFC documents usually include explanations and brief examples, so it should show the “correct” way to implement PATCH.

.

.

...nope, nothing there

...nope, nothing there

Surprisingly, the example request body in RFC-5789 simply says description of changes — no constraints whatsoever. This means developers are free to define the API interface however they want, making implementations like this perfectly valid:

PATCH users/1

{

$increase: 'age',

value: 1,

}Here, the $increase field specifies which property to increment, and value specifies by how much. In this case, Evan’s age increases by 1 every time the API is called (…sad), so this API is not idempotent.

I’ve personally never seen PATCH used this way in practice, but as I mentioned, RFC-5789 places no constraints on how to implement PATCH, so using it this way doesn’t violate any standard.

In short, because the spec places no constraints on implementation details, PATCH may or may not be idempotent depending on how the API is built.

Wrapping Up

REST is really a guideline for designing network architecture, so the “representational state” I discussed is just one piece of it. But since this post aimed to explain RESTful APIs specifically, I didn’t dive into the deeper details. If you’re curious about REST beyond what I’ve covered, I recommend reading the REST chapter from Roy Fielding’s dissertation.

RESTful APIs have been the topic I’ve discussed most frequently with backend developers throughout my career as a frontend developer. Those discussions stemmed partly from a desire to define clear APIs, and partly from wanting to make APIs so clear that new developers joining the team could get up to speed immediately. (I was having this exact conversation at the office today, in fact.)

Personally, I believe the best API isn’t one with the most features or one that’s free to use — it’s one so clear that someone with zero context can look at an endpoint and immediately understand what it does, without any additional explanation.

Sure, learning and following architectural guidelines like RESTful APIs can feel tedious. But the purpose of these standards and guidelines is to create a unified traffic system that millions of developers worldwide can communicate through. Perhaps it’s these small individual efforts to follow the guidelines that, collectively, keep the vast web architecture running smoothly.

That wraps up this post on RESTful APIs — the endpoint where frontend and backend communicate.