HTTP Status Codes: The Server's Way of Talking Back

The small numbers that keep the internet in order

Modern applications are practically programs that run entirely on the network — communication makes up a huge portion of a program’s business logic. Client applications communicate with backend servers to fetch logged-in user information, create new posts, and sometimes subscribe to server events through WebSockets to implement features like push notifications or chat.

In this process, the frontend and backend need to define many rules — from how they’ll communicate, to how resource creation and deletion are defined, to how the success or failure of backend operations requested by the frontend should be reported.

Several guidelines exist to help define these rules, and that’s where things like HTTP methods, status codes, and REST come in.

In this post, I want to dive into HTTP status codes — one of the essential elements for clearer communication between frontend and backend.

Do We Really Need to Follow These Guidelines?

Honestly, HTTP methods, status codes, and REST are just guidelines. Not following them won’t break your program or cause runtime errors for users.

In other words, you can write programs just fine without them.

So it doesn't matter if we don't follow them, right?

So it doesn't matter if we don't follow them, right?

Well, not following these rules is your choice, but considering the side effects that can result, I’d recommend following them whenever possible.

Think About Why Standard Interfaces Exist

Industry standards are established to ensure compatibility among products made by countless different producers and to facilitate communication between them. The set of standard specifications we define to make different entities compatible is what we call an “interface.”

The concept of an interface is quite broad — if it connects things, it’s an interface. HDMI connecting monitors to computers, SATA used in storage devices, USB — they’re all interfaces. UI (User Interface) even extends the concept to connecting humans with machines.

Among these, the interface most familiar to developers is the API (Application Programming Interface). An API provides the functionality needed to build applications as a set of interfaces.

The convenience of APIs is that users only need to know how to use them — they can completely ignore whatever massive logic lies beneath. A classic example is the Windows OS API provided through C:

#include <Windows.h>

#include <tchar.h>

int APIENTRY _tWinMain(

HINSTANCE hInstance,

HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

LPTSTR lpCmdLine,

int nCmdShow

) {

MessageBox(NULL, TEXT("Hello, Windows!"), TEXT("App"), MB_OK);

return 0;

}Developers can display a message box simply by calling the MessageBox API function without knowing how the Windows OS renders it. And this interaction is communication between two entirely different programs — a C application and the operating system.

In other words, an API is an interface for communication between programs. Similarly, when a client requests something from a server, it uses an API defined by specific rules to access server resources. In most modern applications that communicate via HTTP, these APIs are defined using specific URLs called endpoints, and the server must respond to client requests through these endpoints in a consistent manner.

HTTP status codes are a kind of agreement that conveys the result of the client’s request — and they’re a crucial component of an API.

The Frontend’s Sad Story That Backend Devs Don’t Know About

In this section, I want to briefly talk about something that frontend developers working with poorly designed APIs have likely experienced at least once. Backend developers rarely look at frontend application source code, so they might not even know this situation exists.

It’s the case where HTTP status codes are used incorrectly — the classic example being a server that returns 200 OK even when a request fails.

GET /api/users/123HTTP/1.1 200 OK

{ "success": false }APIs designed this way typically include success/failure status and failure reasons in the HTTP response body, which creates an awkward situation for the frontend application.

Frontends handle these async requests through Promises, and the problem is that most HTTP communication libraries and APIs determine success or failure based on the status code from the backend, throwing errors only when requests fail.

So normally, frontend communication code looks something like this:

async function fetchUsers () {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/users/123');

return response.json();

}

catch (e) {

alert('The request failed!');

}

}If a request to the server fails, the server should send a 400 or 500-level status code, which causes fetch to throw an error. With that, a simple try/catch around fetch is all you need to handle communication errors.

But when the backend returns a 200-level code even for failed requests, the frontend ends up in this sad situation:

async function fetchUsers () {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/users/123');

const { success } = await response.json();

if (!success) {

throw new Error();

}

} catch (e) {

alert('The request failed!');

}

}Notice the if (!success) that didn’t exist before. An unnecessary extra layer of error handling that hurts code readability, but the frontend has no choice. You can’t just ignore server errors and skip handling them.

On top of that, if the backend encounters an unhandled error or the server dies entirely, the response will come back with a 500 or 502 error code anyway — so you can’t skip try/catch either.

Every HTTP communication library on the client side is designed assuming correct HTTP status code usage. If the server uses incorrect status codes, these sad situations arise. And honestly, returning the correct status code for each situation isn’t even that hard on the backend side. (Just a bit tedious.)

Like client libraries, most server frameworks also provide HTTP status codes for every situation, so I recommend using the appropriate codes whenever possible.

Now let’s dive into what each of these HTTP status codes actually means.

HTTP Status Codes: Reporting the Result of Your Work

When a client requests work from a server, the server performs the work and sends back the result as a response. It uses HTTP status codes to indicate whether the work succeeded or failed, and if it failed, why. As we saw in the bad example above, some servers include failure information in the response body, but the better approach is to use the correct HTTP status codes.

HTTP status codes have standardized numbers for each situation — “200 = success,” “400 = client screwed up,” “500 = server screwed up.” Basic web program behavior and frontend/backend frameworks are all designed around these standards, so it’s best to follow them.

Web browsers — the quintessential HTTP programs — strictly follow these status code standards. Browsers actually distinguish between success and failure of their requests based on the status code the server returns, and they display this visually.

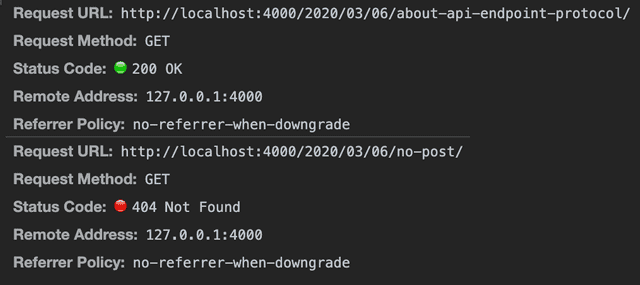

Browsers treat 200-level status codes very differently from 400 and 500-level ones

Browsers treat 200-level status codes very differently from 400 and 500-level ones

If a server returns status code 200 but expresses the error only in the response body, the browser thinks the request succeeded while it actually failed — a bizarre situation.

If the server returns a code like 301, the browser will automatically redirect the user to another page. So if the server doesn’t return proper status codes, the browser could exhibit unexpected behavior.

Now let’s look at what each HTTP status code means. Status codes range from 100 to 500-level and can define quite a variety of states, but you don’t need to know them all. I’ll cover just the ones I’ve personally used at least once.

100-Level

100-level codes carry informational states like “you may switch protocols” or “continue sending requests.” I’ve never actually encountered these in application development, so I’ll skip them.

200-Level

200-level codes indicate that the server successfully performed the work the client requested. Browsers display these with a clean green color in the network tab.

While “request succeeded” alone is often enough, if you need more detailed states, you can actively use 200-level codes to give the client more specific information.

200 OK

Status code 200 simply means the work succeeded. In most cases, the client knows exactly what it requested, so just knowing “your request succeeded” is sufficient — no additional detail needed. That’s why this single code is used for all successful API responses in the vast majority of cases.

201 Created

Status code 201 means the request was processed normally and a new resource was created as a result. Creating new resources through client requests is extremely common — the most representative case I’ve experienced is user registration. A registration request creates a new user row in the database, making it a perfect fit for 201.

204 No Content

Status code 204 means the request was processed normally and the content associated with this request no longer cleanly exists. This code can be used as a response to deletion requests. My experience with it was a post deletion API.

Note that whether the deletion is a soft delete or hard delete is completely irrelevant here. However the server represents resource deletion internally, the only information the client needs is “this resource has been deleted and is no longer available.”

300-Level

300-level codes relate to redirection. When a requested resource has been moved or deleted and can no longer be accessed normally, the server can tell the client “go here to find the resource you’re looking for” — and that’s what 300-level codes are for.

301 Moved Permanently

Status code 301 is also known as “301 Redirect” — the most commonly used redirection code. When a browser receives 301 in response, it checks the Location field in the HTTP header and automatically redirects to the URL specified there.

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Location: https://evan/moved-contents/1234Search engine bots like Google’s also automatically update page information when they receive a 301 response, making correct use of this status code very important from an SEO (Search Engine Optimization) perspective.

Redirection settings can typically be configured in the server engine’s configuration files or directly in the backend application. A common use case is redirecting users who connected via HTTP to the HTTPS-only port.

server {

listen 80;

server_name evan.com;

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

}

server {

listen 443 ssl;

server_name evan.com;

...

}In this case, when Nginx detects a user connecting to port 80, it redirects them to port 443 (which requires HTTPS), enforcing the secure protocol.

304 Not Modified

Status code 304 means the requested resource hasn’t changed at all compared to the previous request. Literally: Not Modified.

When the server responds with this code, the client doesn’t need the server to retransmit the resource — it uses its cached version instead, reducing unnecessary communication payload.

Since the client uses its cached resource rather than one received from the server, this is considered a redirection to the cached resource. That’s why 304 is sometimes called an implicit redirect.

Browsers have their own caching mechanisms for this response. If a 304 response is received but there’s no cached resource, a blank screen or error page appears. So if you encounter this situation, you might want to check whether the browser actually has a cached resource.

400-Level

400-level codes mean something was wrong with the client’s request. If you spot one, there’s a high probability the frontend developer didn’t handle edge cases properly or sent bad data with the request. (There’s a small chance it’s the backend’s fault too…)

400 Bad Request

Status code 400 is one of the most common 400-level codes, and it bluntly means “the client sent a bad request.” What exactly went wrong is sometimes included in the response body, but when it’s not, you might need to dig into the backend application logs.

401 Unauthorized

Status code 401 tells an unauthenticated user requesting a protected resource “you need to authenticate.” It’s commonly used when a non-logged-in user calls an API that requires login.

When the client receives 401, it often interprets this as “login required” and redirects the user to the login page.

403 Forbidden

Status code 403 means the client requested a forbidden resource. This code is sometimes confused with 401 Unauthorized — the meanings seem ambiguous, but there’s one clear difference.

401 literally means unauthenticated — the backend can’t identify who the current requester is. The server is saying “identify yourself!”

With 403, however, the backend doesn’t care at all who the requester is. Whether the client identified themselves or not, authenticated or not — accessing this resource is unconditionally forbidden.

Servers may also return 403 when a resource requiring HTTPS is accessed via HTTP.

404 Not Found

Status code 404 simply means the requested resource doesn’t exist.

405 Method Not Allowed

Status code 405 means the wrong HTTP method was used for the current resource. Many backend frameworks automatically return 405 when a controller doesn’t have logic for the requested method.

406 Not Acceptable

Status code 406 means that even after server-driven content negotiation, no suitable content type was found.

When a client requests a resource, it uses the Accept header field to specify what content types it wants. If this field isn’t explicitly set, browsers typically fill in a few default types like text/html.

GET http://evan.com/

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml,*/*

...The server checks the Accept field from left to right, looking for a content type that matches the requested resource. If found, it specifies that type in the response’s Content-Type header.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/htmlSince the server decides which content type to return, this process is called “server-driven content negotiation.” In the example above, the first-priority text/html was returned. If text/html doesn’t exist, the server tries application/xhtml+xml, then application/xml, and so on.

If none of the listed types are available, the wildcard */* at the end catches everything, and the server responds with whatever content type it has. But if even after checking all requested types no matching resource exists, the server returns 406: “no resource matching your requested content types.”

408 Request Timeout

Status code 408 means the connection between client and server was established, but the request body never arrived.

HTTP communication first establishes a connection, then transmits the request body data. 408 occurs when the connection was properly established but the server never receives the request body no matter how long it waits.

429 Too Many Requests

Status code 429 occurs when the client sends too many requests to the server. “Too many” could mean firing off requests so rapidly that the server says “whoa, calm down.” For paid APIs, it can also mean “you’ve exceeded your allowed request count — pay more.”

The server can include a Retry-After header with the 429 response to tell the client “try again after this amount of time.”

500-Level

500-level codes mean something went wrong on the server side. If you spot one, something is broken on the server — time to have a word with the backend developer.

500 Internal Server Error

Status code 500 means some unknown error occurred in the backend application. It’s usually an unhandled error, which is why the error cause isn’t communicated to the client. (More like it can’t be communicated in most cases.)

Exposing unhandled error details to the client also poses a significant security risk, so 500 typically just signals that an error occurred. If you encounter this, I recommend checking server logs or leveraging error monitoring solutions like Sentry or Bugsnag.

502 Bad Gateway

The most common scenario for status code 502 is when the backend application has died. But why does it say “Bad Gateway” instead of something more direct like “Server Died”?

Because no matter how simple a backend architecture is, it’s never just a single application. The “gateway” here refers to an abstract connection point between applications, and as the name implies, backend architectures are typically composed of at least two or more applications.

In typical setups, client requests don’t go directly to the backend application. There’s usually a server engine like Apache or Nginx, or a load balancer, sitting in front to receive requests and forward them to the backend application.

server {

listen 80;

server_name evan.com;

location / {

proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:3000;

proxy_http_version 1.1;

proxy_set_header Upgrade $http_upgrade;

proxy_set_header Connection 'upgrade';

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_cache_bypass $http_upgrade;

}

}With a typical Nginx setup like this, Nginx listens on port 80, receives HTTP requests, and forwards them to the backend application running on port 3000.

This architecture exists for security and processing efficiency. Backend applications aren’t bulletproof, so you can’t blindly feed them all requests. And expecting clients to always send safe requests is equally unrealistic.

Plus, simple requests that just need to locate and serve files don’t need to bother the already-busy backend application — the server engine can handle those directly.

So the backend places a proxy server at the front to act as a gatekeeper. The abstract passage connecting this proxy server to the backend application is called the “gateway.” When the backend application dies, the gatekeeper proxy receives no response and sends 502 Bad Gateway to the client.

503 Service Unavailable

Status code 503 means the server isn’t ready to handle requests. It’s sometimes used similarly to 502 Bad Gateway, but 503 implies a temporary situation — typically when the server is under heavy load and doesn’t have the capacity to handle the current request.

In AWS Lambda, this can occur when processing a request requires more resources than the concurrent container execution limit, or when a task’s processing time exceeds the container’s maximum lifespan setting.

Since 503 indicates a temporary situation, it can also use the Retry-After response header — same as 429 Too Many Requests — to tell the client “try again after this amount of time.”

504 Gateway Timeout

Status code 504, like 408, indicates a request timeout. However, 504 isn’t caused by the client’s request timing out — it occurs within the backend architecture, between servers communicating with each other.

As I mentioned, backend architecture isn’t just a single application. Even after a client’s request reaches the server, internal communication between backend applications continues. If Nginx (acting as a proxy) forwards a client request to the backend application but receives no response within a set time, Nginx returns 504 Gateway Timeout to the client.

Wrapping Up

I originally planned to cover RESTful APIs alongside HTTP status codes in this post, but once again I failed spectacularly at controlling the length and had to split it into separate posts. (This is happening more and more frequently…)

As I mentioned, not following standards like status codes won’t cause program errors, so they’re easy to brush off. But defining clearer interfaces makes program behavior more predictable and greatly helps communication between frontend and backend developers — so I recommend following the standards whenever possible.

That wraps up this post on HTTP status codes — the server’s way of talking back.