How Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Functors and monads: the magic that solves the problems ruining function composition

Writing code in functional programming means expressing the various tasks a program needs to perform as functions, then skillfully composing those functions to build a large program.

Function composition is the very foundation of this paradigm, which makes it enormously important. The problem is that all sorts of practical issues pop up during the process of composing functions.

The biggest reason these issues arise is simple. No matter how much we use pure functions, they can never be perfectly identical to mathematical functions. Programming and mathematics are similar but fundamentally different disciplines.

So brilliant minds around the world started bringing in mathematical concepts like functors and monads to solve these problems. The catch? These concepts are far too abstract and arcane to understand intuitively.

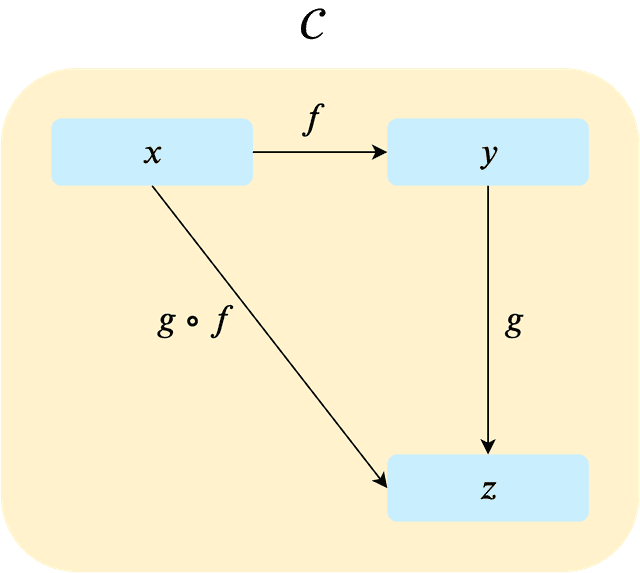

A functor explanation diagram that makes you want to cry just looking at it...

A functor explanation diagram that makes you want to cry just looking at it...

When I was studying functors and monads, the resources I found through Google fell into roughly two categories: “terrifyingly difficult mathematical explanations” and “code examples.”

The problem was that there were very few resources bridging the gap between the two. In other words, I couldn’t find many resources that clearly explained exactly which programming problems functors and monads were introduced to solve. (Or maybe everyone else understood and I was just too dense to get it.)

But I didn’t want to use functors and monads without properly understanding why, so I decided to investigate and figure it out myself.

In this post, I want to talk about what problems arise when you carelessly combine functions in functional programming, and how those problems can be solved.

Everything Is Built from Function Composition

Let me say it again: functional programming is a paradigm where you express a program’s tasks as functions, then compose those functions to build a large program.

The most important keyword in this definition is “function composition.” The reason functional programming is so vigilant about side effects is ultimately because you need to be able to predict a function’s inputs and outputs in order to compose functions safely.

In the world of functional programming, every action inside a program is expressed as a function — even assigning a value to a variable or performing simple arithmetic.

// Imperative programming

const foo: number = 1;

foo + 2;

// Functional programming

const foo = ((): number => 1)();

const add2 = (x: number): number => x + 2;

add2(foo);This program simply declares a number variable and adds 2 to it.

In the imperative version, variable assignment could be expressed as simply as foo = 1, and the operation as foo + 2. In the functional version, the assignment becomes a function that returns 1, and the operation becomes add2(foo).

The part we should focus on is the very last line: add2(foo).

add2(foo) means using the output of the anonymous function assigned to foo — the value 1 — as the input to add2. This act is function composition.

// A more simplified version looks like this

const add2 = x => x + 2;

add2( (() => 1)() );In a world where even simple operations like assigning values and adding numbers must be expressed as functions, building a robust large-scale program hinges on how well you can compose various complex functions.

This might seem like a simple concept, but you can’t just compose any functions willy-nilly. There’s one critically important rule for function composition: the domain and range of the functions being composed must match.

Domains and Ranges Must Match for Composition

As I discussed in Pure Functions – A Programming Paradigm Rooted in Mathematics, functional programming uses pure functions to minimize side effects.

The two key characteristics of pure functions are:

- Don’t modify or reference state outside the function!

- Given the same input, always return the same output!

Using pure functions makes it easier for developers to predict function behavior, which helps with debugging. But more fundamentally, if these rules aren’t followed, functions can’t be composed at all — making it impossible to build programs by expressing everything as functions and combining them.

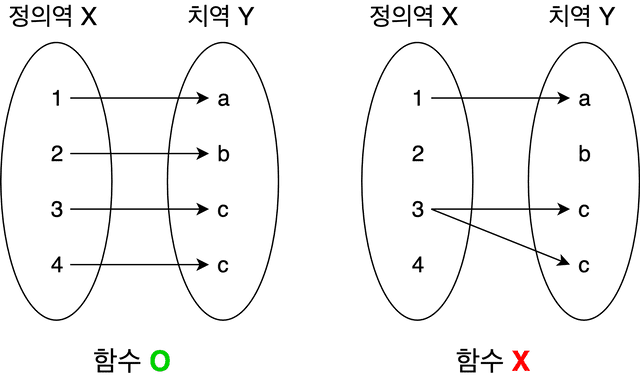

Why do these rules need to be followed for composition to work? Since pure functions are a programming implementation of mathematical functions, let’s first look at how mathematical functions behave.

Mathematical functions have a domain — the set of possible input values — and a range — the set of possible output values.

Each element in the domain must map to exactly one element in the range. In other words, the same input must always produce the same output. If this rule breaks, it’s no longer a function — it becomes something else entirely.

Simply put: pick one value from the designated set of possible inputs and throw it into the function, and exactly one value from the designated set of possible outputs will come out.

If that’s true of mathematical functions, then pure functions — their programming counterparts — must also have something equivalent to a domain and range. What would those be in the programming world?

.

.

They’re types.

If you think about it, types in programming are really a kind of set. The number set contains elements like {-1, 0, 0.1, 1, 2, NaN, Infinity...}, the boolean set contains {true, false}, and the string set contains every string that can be created programmatically.

Looking at the add2 function from earlier, we can see it takes a number type value and returns a number type value.

const add2 = (x: number): number => x + 2;We can say that add2 has number as both its domain and range. We can define the domain and range of other function types using the same rules.

type f = (): number => string; // Domain: number, Range: string

type g = (): Array<string> => boolean; // Domain: Array<string>, Range: boolean

type h = (): string => boolean; // Domain: string, Range: booleanThe commonalities between mathematical functions and programming pure functions are starting to become clearer.

Now let’s get to the main topic: function composition. In mathematics, composing functions is extremely common — there’s even a dedicated symbol for it.

The composite function of functions and can be expressed with this simple formula:

If the sudden math gives you a headache, just think of as “eating a meal,” as “clearing the dishes,” and the composite function as “eating a meal and clearing the dishes.” Functions are inherently that abstract.

In this formula, functions execute from right to left. Using the composite function as is actually identical to composing functions as .

But if we keep nesting functions to represent composition, any formula with many composed functions would be nothing but parentheses. That’s why we use the circle operator to lay out the composed functions in a readable way. (Think of the difference between callbacks and async/await.)

// Without a composition operator, it would look something like this...

foo(b(a(h(f(g(x))))));When composing functions, there’s an important principle: the range of the first function must match the domain of the next function .

Since we said that a pure function’s domain and range are types, we can also say that the first function’s output type must match the next function’s input type.

// Composition is possible!

f: number => number

g: number => number

// This can't be composed...

f: number => string

g: number => numberThe domain-and-range talk might have sounded complicated, but translating it to types makes it blindingly obvious. So if we use pure functions and follow this rule, are we free from problems?

Well, in most cases yes — but sadly, not all. The programming world has cases that don’t exist in mathematics, like errors and uncertainty.

Even pure functions — programming implementations of mathematical functions — can’t escape these cases as long as they exist in the programming world.

Because these problems persist even with pure functions, brilliant minds around the world started wondering “how can we safely compose functions?” — and the concepts they introduced to answer that question were mathematical ideas like functors and monads.

Side Effects Exist Even in Pure Functions

“Side effect” literally means “secondary effect.”

Any secondary effect that occurs beyond what we expect from a function is a side effect. A function being affected by external state is just one representative example.

Compared to mathematical functions, pure functions are actually quite flimsy beyond the guarantee that “the same input always produces the same output.” Consider a function that takes a string and returns its first character:

function getFirstLetter (s: string): string {

return s[0];

}This is a pure function. Its output depends only on its argument, it always returns the same output for the same input, and it’s not affected by any external state.

getFirstLetter is a pure function that returns the first character of a given string — but if an empty string is passed as an argument, it will return undefined instead of a string.

Can we really guarantee that this function will always return a string type?

If we assumed getFirstLetter would definitely return a string and composed functions accordingly, we’d run into a type error like this:

function getStringLength (s: string): number {

return s.length;

}

getStringLength(getFirstLetter(''));Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'length' of undefinedEven this error is a side effect. It’s a secondary effect occurring beyond what we expected from our pure function.

When multiple functions are composed and even a single one throws an error, the entire composed operation falls apart. That’s why we must manage these side effects.

In truth, getFirstLetter’s range isn’t just string — it’s a string|undefined union. So we could solve this by redefining both functions’ domains and ranges and adding error handling:

function getFirstLetter (s: string): string|undefined {

return s[0];

}

function getStringLength (s: string|undefined): number {

if (!s) {

return -1;

}

return s.length;

}But once a function starts having a range that’s a union of multiple types, every function that composes with it also needs a domain that’s a union — resulting in cancerous types like type|undefined spreading across every function.

On top of that, checking for value existence inside every function with conditional logic is tedious, and duplicating the same code everywhere means this isn’t a fundamental solution.

This uncertainty about what type a function might return ultimately hinders clear type usage during composition — where domains and ranges must match — making it a side effect we absolutely must address.

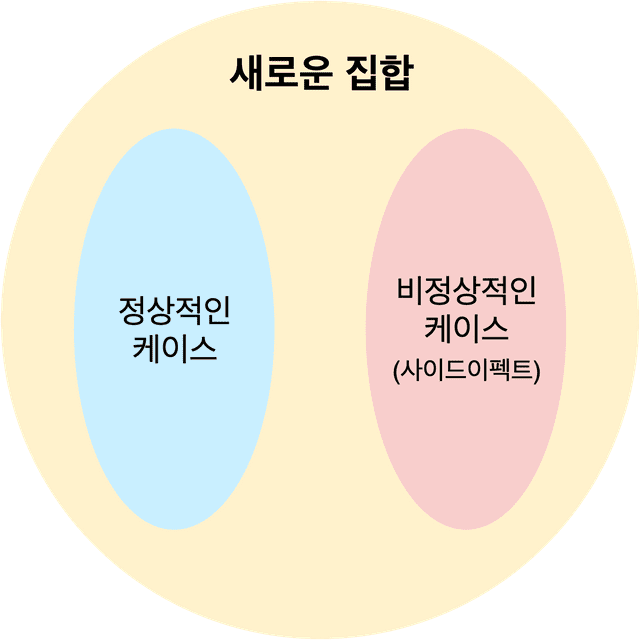

How Should We Manage Side Effects?

The reason this happens is simply that “computers aren’t math.” Every function running in a program has these issues. Even pure functions.

Fundamentally, the question is: how can we manage the unavoidable side effects that arise during function composition?

Can we safely complete a composed operation even if a function in the middle throws an error? Can we make uncertain function outputs clear before passing them to the next function?

What if we wrap the function in another function that safely handles exceptions, or skip the next function if a weird value comes out?

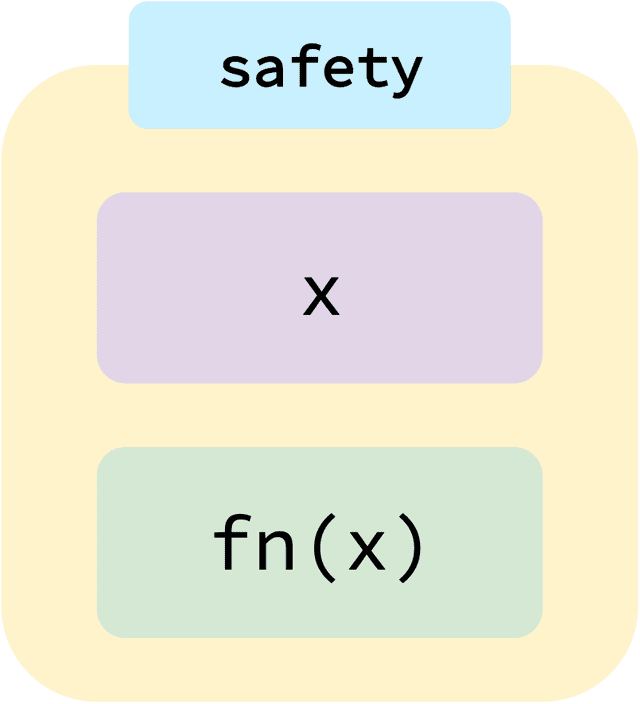

type StringFunction = (s: string) => number;

function safety (x: string|undefined, fn: StringFunction) {

return x ? fn(x) : x;

}

safety(getFirstLetter('Hi'), getStringLength);

safety(getFirstLetter(''), getStringLength);1

undefinedBut this approach seems hard to apply to functions with all sorts of input/output types, so let’s make it more flexible with generics.

function safety <T, U>(x: T|undefined, fn: (x: T) => U) {

return x ? fn(x) : x;

}

safety<string, number>(getFirstLetter('Hi'), getStringLength);

safety<string, number>(getFirstLetter(''), getStringLength);1

undefinedNow we’re getting somewhere. Essentially, the safety function takes a value of T or undefined. If the value is undefined, it returns undefined as-is. Otherwise, it passes the value to a function that takes T and returns U, and returns that function’s result.

Has value: T -> fn<U>

No value: T -> undefinedInstead of directly connecting getFirstLetter’s range to getStringLength’s domain, we’ve safely composed the functions by wrapping the side effect with x ? fn(x) : x logic.

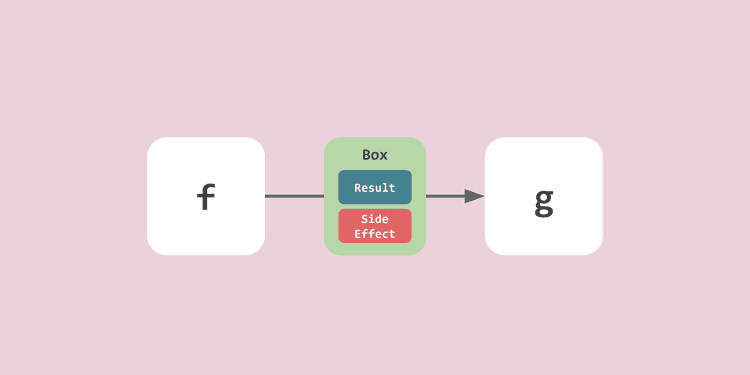

What if we extended this concept — what if some kind of safety wrapper always surrounded a function’s output value? If we could create something that wraps both a function’s normal result and its side effects, couldn’t we solve this problem?

If that abstract something could manage function side effects while enabling composition with other functions, we could compose freely without handling exceptions at every step — maintaining type safety for function inputs and outputs.

// Something like this!

f: Something<number> -> Something<number>

g: Something<number> -> Something<number>A function might return a proper value from its range, or it might return a value like null or undefined that could cause side effects. But as long as that Something can handle exceptions on its own, we can compose functions without worrying about those details.

And with this approach, beyond just managing null or undefined, we could wrap various kinds of logic around values — making it a reasonably extensible concept. Something like:

Maybe<T> = The value may or may not exist

Promise<T> = No value right now, but you'll get one when it's ready

List<T> = May contain multiple values of the same kindAnd to use this value-wrapping something effectively, we’d need to freely transform the internal value — so we’d also need something capable of operations like Maybe<T> -> Maybe<U>.

After this kind of deliberation, developers borrowed a mathematical concept that serves a similar role. That concept is the functor.

What Is a Functor?

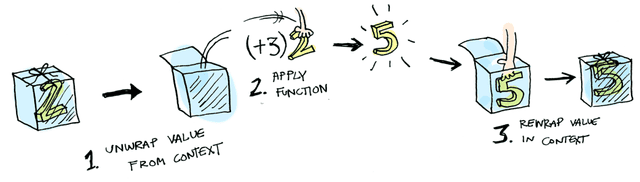

Functors are commonly explained as some kind of box that holds a value. As I described above, a box is an apt metaphor for something that can wrap and handle both a function’s normal results and its side effects.

[Source] http://adit.io/posts/2013-04-17-functors,_applicatives,_and_monads_in_pictures.html

[Source] http://adit.io/posts/2013-04-17-functors,_applicatives,_and_monads_in_pictures.html

This box might contain logic that helps you use values safely, logic that can process multiple values, logic that makes values available once they’re determined in the future — it’s a magical box containing various kinds of logic that assist in using values.

Since this box isn’t limited to a fixed role and can have various capabilities like Maybe or Promise, it’s also called a “context.”

The safety function we created earlier can be thought of as a kind of box wrapping values.

function safety <T, U>(x: T|undefined, fn: (x: T) => U) {

return x ? fn(x) : x;

}The point is that instead of using the value x directly, we’re putting x into the safety function — so we can think of the safety function as a kind of box.

Conceptually, that’s really all there is to functors. From here, you just need to learn how to implement them and you’re good to go. But since this post aims to dig deeper into what functors really are, I want to talk about the more fundamental concept behind them.

Categories

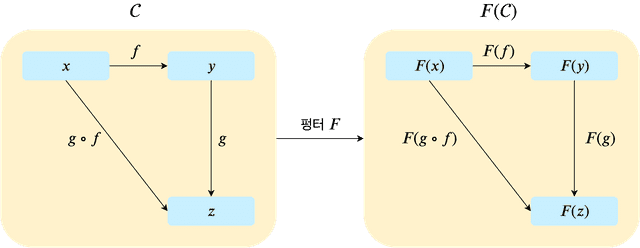

A functor is a concept from Category Theory in mathematics, defined as a structure that can define relationships between categories that share the same structure.

To understand what a functor fundamentally is — and why we need functors for safe function composition through Something<type> — you need to know what a category is.

The mathematical concept of a category isn’t actually that different from how we use the word “category” in everyday life. It’s roughly… a grouping of similar things.

With that relaxed mindset, if you search for Category Theory on Wikipedia, you’ll find something like this:

A category consists of the following data:

- A collection of objects. Elements of this collection are called “objects” of .

- For any two objects , a collection of morphisms from to . The collection of all morphisms in is denoted .

- For any three objects , a binary operation , called composition of morphisms. The composition of and is denoted or .

…

Wikipedia Category (mathematics)

Huh...?

Huh...?

The general idea of category theory is actually something anyone can understand. It’s just that mathematics is inherently abstract, and explaining things in everyday language would be too long and complex, so mathematicians use condensed words and symbols. (This is honestly one of the reasons people give up on math.)

As I mentioned, a category in math is basically the same concept as categories on a shopping site. The difference is that mathematical categories are more abstract — they could be categories of objects, of natural numbers, or even of functions.

According to the definition above, a category consists of “objects” and “morphisms.”

An object is simply an item within a category. In a fashion shopping site’s product category, the objects would be shirts, sweatshirts, outerwear, and coats. In a category of natural numbers, the objects would be 1, 2, 3, and so on. So far, this feels similar to how we use “category” in everyday life.

But a mathematical category also has morphisms.

Looking at the definition again, a morphism is something with a domain and a codomain for any two objects . The notation just means objects and are in category , so we can skip that. The keywords we should focus on are “domain” and “codomain.”

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear “domain” and “codomain”? That’s right — functions. Saying that is the domain and is the codomain means that applying some morphism (function) to object produces .

const objectA = 1;

const morphismAdd1 = x => x + 1;

// Applying the morphism add1 to object A...

morphismAdd1(objectA);2 // Produces object BIn other words, a morphism is essentially a function that represents the relationship between objects. That’s why we can express it mathematically as and programmatically as the lambda (a) => b. (There are cases where morphisms aren’t functions depending on the type of objects, but let’s not go there.)

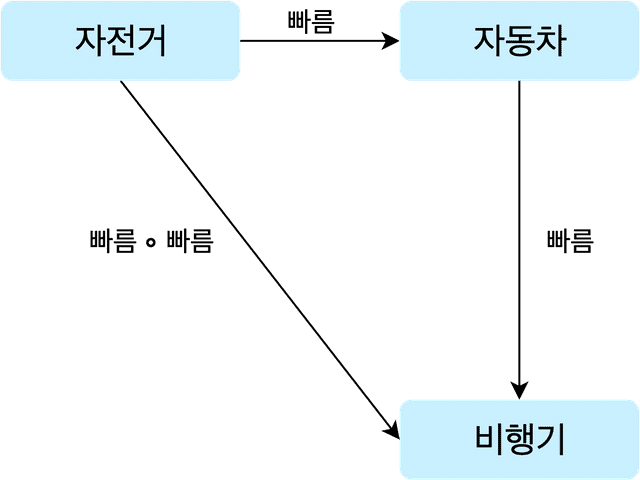

Now that we understand this much, let’s grab a simple category and play with it.

Imagine a category with this structure. The objects are bicycle, car, and airplane, and the morphisms are the faster arrows between them.

In this category, applying the faster morphism to bicycle produces car, and applying faster to car produces airplane. When we say morphisms express relationships between objects, this is what we mean. A bicycle made faster becomes a car, and a car made faster becomes an airplane.

And since applying a morphism is the same as applying a function, we can express this category’s structure in simple code.

const category = ['bicycle', 'car', 'airplane'];

function faster (category, object) {

const index = category.findIndex(v => v === object);

return category[index + 1];

}

faster(category, 'bicycle');

faster(category, 'car');'car'

'airplane'And the faster faster morphism drawn directly from bicycle to airplane represents the composition of two faster morphisms. In code, that’s faster(faster('bicycle')) === 'airplane' — two composed function calls.

Expressing morphism composition in programming is nothing more and nothing less than composing functions. This simple idea looks like this when stated in mathematical terms:

For any three objects , a binary operation , called composition of morphisms. The composition of and is denoted or .

The three objects in this definition correspond to bicycle, car, and airplane from our category. And the in refers to a collection of morphisms — a set of morphisms.

The reason there can be multiple morphisms is straightforward. Even in our category, the relationship between bicycle and car isn’t limited to just faster:

- bicycle -faster-> car

- bicycle -more expensive-> car

- bicycle -larger-> car

- bicycle -has an engine-> car

Multiple morphisms can exist between any two objects, so mathematicians lump their collection together and call it .

You might wonder why we need to care about all these details, but mathematics is a discipline where answers must be definitive and exceptions are never allowed, so definitions must account for every possible case.

And refers to applying just one morphism from the collection to objects and . We don’t know which morphism will be applied, but only one can be applied at a time. (Applying multiple simultaneously would require a quantum computer.)

Finally, just as we applied the faster morphism twice to bicycle, composing morphisms and is denoted — morphism composition.

In other words, applying morphism to the object “bicycle,” then applying morphism , produces the object “airplane.” In code: g(f('bicycle')) === 'airplane'.

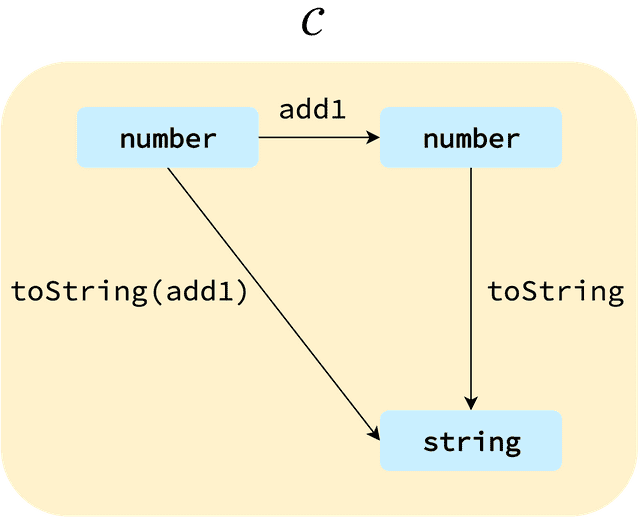

Category theory is such an abstract theory that everything happening inside a program can be expressed as category models. Likewise, the process of applying functions to values and composing them in functional programming can also be represented as a category model.

Personally, I believe this is all you need to know about category theory to understand functors more easily. Once you accept that things happening in a program can be defined as categories, understanding functors becomes straightforward.

Functors

Now let’s transform our simple category into a more abstract model. Replace the names bicycle, car, and airplane with variables x, y, z, and replace the morphism faster with variables f and g.

After abstracting our category this way, it feels like there should be other categories with the same structure — not just category .

And that makes sense, because categories with this structure of objects and morphisms are extremely common — frankly, it’s a universal pattern that can be fitted to almost any definition.

So if we can apply morphisms to objects to transform them into other objects, couldn’t we apply something to a category to transform it into another category?

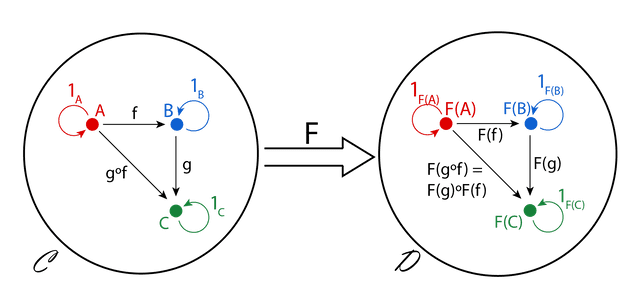

That’s exactly where the functor comes in. A functor is a morphism (function) that can transform one category into another.

No matter how complex category is, we can simply wrap the category with a functor like and use it. Then all objects and morphisms inside the functor-applied category are wrapped in the function .

The most important point is that wrapping with a functor never changes the category’s structure itself. In the diagram above, you can see that while has been applied to the objects and morphisms, the shape of the arrows hasn’t changed.

const objectX = 1;

const objectY = 2;

const morphismF = x => x + 1;

morphismF(objectX) === objectY; // trueconst objectX = functor(1);

const objectY = functor(2);

const morphismF = functor(x => x + 1);

morphismF(objectX) === objectY; // trueEven when using a functor, the rules the category has are never changed. Put simply, it safely wraps objects and morphisms without causing any other side effects.

Remember when I said everything in programming can be expressed as a category?

No matter how complex a category is, simply wrapping it with a functor transforms it into another category without touching the original category’s structure. This fits perfectly with the need we identified: “wrap values to use them safely.”

Let’s Build a Functor!

A functor isn’t a grand concept. Simply put, if something can transform one category into another, it’s a functor.

The act of a functor transforming a category is called “mapping” — more precisely, applying a function to a category to transform it into another category.

Because functors are such an abstract concept, everyone describes them differently — “I use functors for this,” “I use functors for that.” A functor is merely something capable of mapping, so the possibilities are endless depending on how you apply it.

Since the concept of a functor just needs to allow transforming the internal value through a specific method, expressing it in code isn’t that hard.

interface Functor<T> {

map<U>(f: (x: T) => U): Functor<U>

}

Functor<T>: This functor holds a value of typeT.map<U>: Applying this functor’s morphism yields a new functor holding a value of typeU.f: (x: T) => U: The morphism works by taking a value of typeTand outputting a value of typeU.

The map method applies the (x: T) => U function passed as an argument to the functor’s internal value, and returns a new functor wrapping the transformed value.

The function passed to map is what actually transforms the functor’s internal value. This function is called a “transform” function.

The reason mapping returns a functor wrapping the transformed value — rather than the raw value itself — is that a functor is fundamentally a structure that transforms one category into another. It doesn’t destroy the category and extract the objects inside.

And since a functor merely represents a new category, it must not modify the original category’s objects. That’s why instead of updating the existing functor’s value, it creates and returns a new functor containing the transformed value.

If this feels confusing, think about Array.prototype.map. When you think about it, an array is a kind of functor too — a box holding values.

// Functor<number>

const array: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3];

// Transform function: (x: number) => string

const toString = v => v.toString();

// Mapping!

array.map(toString);// New functor Functor<string>

['1', '2', '3']We can use the transform function toString to change the values inside the array functor, but we don’t destroy the box (the array) itself.

Because the map method we commonly use is attached to Array, it’s easy to associate mapping with iteration. But mapping isn’t that specific an operation.

Whether map internally iterates, bangs a drum, or does a breakdance — as long as it ultimately performs the transformation Functor<T> -> Functor<U>, it qualifies. You should now have a sense of how functors work.

Time to implement a functor ourselves. Since functors are such an abstract concept, the possibilities are endless depending on how you apply them. But this post is already quite long, so I can’t showcase many. Other developers have written great posts with functor implementations, so check those out if you’re curious.

In this post, I’ll build the simplest functors — Just and Nothing — then combine them into a Maybe functor that manages side effects caused by the presence or absence of values.

Just

The Just functor simply wraps a value with no additional functionality, and allows that value to be transformed through its map method.

class Just<T> implements Functor<T> {

value: T;

constructor (value: T) {

this.value = value;

}

map<U> (f: (x: T) => U) {

return new Just<U>(f(this.value));

}

}Just is a simple functor that holds a value internally. Using its map method means transforming the functor’s T type value into a U type value and wrapping it in a new Just functor.

new Just(3)

.map(v => v + 1000)

.map(v => v.toString)

.map(v => v.length);Just { value: 4 }Nothing

The Nothing functor, as the name suggests, holds no value internally. Since there’s no value to apply a transform function to, its map method does nothing and simply returns a Nothing functor.

class Nothing implements Functor<null> {

map () {

return new Nothing();

}

}

new Nothing().map().map().map();Nothing {}Why do we need a functor that explicitly represents the absence of a value?

Because once you start composing functions with functors, all values in the operation must also be wrapped in functors. If you try to apply a plain function to a functor-wrapped value, you’ll naturally get an error.

const foo = new Just(3);

foo + 2;Operator '+' cannot be applied to types 'Just<number>' and 'number'.So once you start composing functions with functors, you must keep using functors until the composition is complete. The whole point of using functors is to maintain type safety and manage side effects during composition — if even one non-functor sneaks in, the entire composed operation’s safety can’t be guaranteed. (One bad apple spoils the bunch.)

This might sound inconvenient, but think about how we use Array — which I described as a representative functor. It’s not such a strange concept.

If you have new Array(3) and want to add 2 to the value it holds, how would you do it? Remember, in functional programming, state mutation isn’t allowed, so you can’t use an approach like new Array(3)[0] += 2.

In functional programming, where immutability is paramount, if you want to change a value inside an array, the only way is to create “a new array with the changed value.”

That’s why we must use the map method to change array values while preserving immutability. Now you can probably see why a functor’s map method creates and returns a new functor after transforming the value.

Maybe

If you’ve followed along this far, let’s build a more complex functor. The Maybe functor’s map method applies the given function to the internal value if it exists, and returns a Nothing functor if it doesn’t.

class Maybe<T> implements Functor<T> {

value: Just<T> | Nothing;

constructor (value?: T) {

if (value) {

this.value = new Just<T>(value);

}

else {

this.value = new Nothing();

}

}

map<U> (f: (x: T|null) => U) {

if (this.value instanceof Just) {

return this.value.map<U>(f);

}

else {

return new Nothing();

}

}

}const getFirstLetter = s => s[0];

const getStringLength = s => s.length;

const foo = new Maybe('hi')

.map(getFirstLetter)

.map(getStringLength);

const bar = new Maybe('')

.map(getFirstLetter)

.map(getStringLength);

console.log(foo); // Just { value: 1 }

console.log(bar); // Nothing {}With the Maybe functor, we can compose functions with confidence, without worrying about null or undefined breaking the composition chain.

Of course, you’ll eventually need an if statement to distinguish whether the final result is Just or Nothing. But at least you don’t need to check at every step during composition. In other words, when composing functions, you can focus solely on the composition.

// Without functors, you can't freely compose functions

const firstLetter = getFirstLetter('');

if (firstLetter) {

console.log(getStringLength(firstLetter));

}

else {

console.log('Composition failed');

}// With the Maybe functor, you can compose with peace of mind

const result =

new Maybe('')

.map(getFirstLetter)

.map(getStringLength);

if (result instanceof Just) {

console.log(result);

}

else {

console.log('Composition failed');

}With just the simple concept of wrapping a value and being able to transform its contents, we’ve achieved safe function composition.

In this post, I only used the Maybe functor as an example for managing side effects from value presence/absence. But as I’ve said multiple times, a functor is just a box wrapping a value — depending on what logic you implement, you can create wildly different functors.

For instance, Promise — which guarantees a future value even though there’s no value right now — can be seen as a kind of functor. And Array — which can store multiple values sequentially — is also a kind of functor.

A functor is an abstract concept, not a concrete implementation performing specific logic. It’s so versatile that with just the concept of wrapping a value and transforming it, you can let your imagination run wild and create all sorts of functor implementations.

Closing Thoughts

Some readers may have thought while reading about functors: “Wait, isn’t this a monad?”

To be precise, that’s half right and half wrong. A monad is ultimately a type of functor designed for safe function composition. Simply put, a monad is a morphism between two functors that satisfies certain special mathematical conditions.

I didn’t cover applicative functors or monads in this post, but setting aside the theoretical details, the reason these additional concepts exist boils down to exactly one thing:

Huh…? Functors alone can’t solve this either…?

We used functors to achieve safe function composition, but in practice, there are plenty of cases where functors fall short. Like when you need to map over a value wrapped in multiple layers of functors. In such cases, functor mapping alone can’t compose functions.

Think of applicative functors and monads as more abstract and powerful versions of functors, designed to cover even the edge cases that basic functors can’t handle.

I actually wanted to explain monads in this post too, but explaining monads the same way I explained functors here would require diving deeper into category theory beyond the overview level, so I gave up. (I’ll tackle monads in the next post.)

Understanding the relationship between function composition and functors is admittedly quite abstract and not easy to grasp. Some developers just learn how to use functors and monads and move on with their programming. But personally, I think knowing why these concepts are used and where the ideas came from makes programming a lot more fun.

This concludes my post: How Can We Safely Compose Functions?

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Beyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingWhy Do Type Systems Behave Like Proofs?

ProgrammingFrom State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingMisconceptions About Declarative Programming

ProgrammingHow to Keep State from Changing – Immutability

Programming/Architecture