How to Keep State from Changing – Immutability

Programming that protects state: the meaning and value of immutability

In this post, I want to talk about immutability — a concept that functional programming values highly, following up on pure functions.

Whenever you explain pure functions, immutability inevitably comes up at least once. Most explanations either define it briefly as “not changing state,” or list behaviors that violate immutability and frame them as forbidden practices.

But personally, I think this style of explanation may not resonate with people who don’t have a solid understanding of state and memory. So in this post, I want to talk about what “immutable” actually means.

What’s the Relationship Between Pure Functions and Immutability?

As I discussed in my previous post, Pure Functions – A Programming Paradigm Rooted in Mathematics, pure functions are a model that brings mathematical functions into the programming world.

The programming world has the concept of state — values that can be stored, modified, and retrieved — but in mathematics, no such concept exists. Every function exists independently, completely unaffected by anything outside itself.

Because pure functions are a programming implementation of mathematical functions — which have no concept of state — they naturally carry the rule that they must not be affected by external state.

And since mathematics has no concept of state, there obviously can’t be a concept of changing state either. We call this “immutability.”

But in the programming world, not changing state requires quite a bit of care. So we establish rules like “don’t reassign values to variables” and program while maintaining immutability.

However, if you understand the fundamental causes of mutation in programs and can uphold immutability on your own, you’ll be able to handle even edge cases that rules alone can’t cover. That’s why we need to understand what immutability actually means.

What Is Immutability?

Immutability is usually defined simply as “not changing state.”

But most explanations only go as far as listing prohibited behaviors — “don’t access or reassign external variables,” “don’t modify function arguments” — without explaining in detail what “changing state” actually means.

So this kind of explanation may not land well for someone who doesn’t know precisely what it means to change state.

What exactly does the “state change” that immutability refers to mean? Is it simply not modifying or reassigning program variables?

In fact, the “state change” that immutability talks about isn’t just about reassigning variables. More precisely, it means any act of modifying a value already stored in memory — and variable reassignment is just one example of that.

In other words, to properly understand state change, you need some basic knowledge of how computers store values in memory and access them.

We Access Memory Through Variables

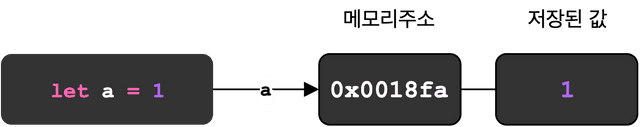

Most programming languages provide variables — a feature that makes it easier to access values stored at specific locations in memory.

Since variables are the very first thing you learn when studying programming, every developer knows this concept. Let’s declare a simple variable.

let a;

a = 1;

console.log(a);1I “declared” a variable called a, and on the next line, “assigned” the value 1 to it.

Normally we’d write let a = 1; to declare and assign simultaneously, but since declaration and assignment are technically different operations, I split them for clarity.

When you declare a variable with let a;, JavaScript allocates a memory space accessible through the variable a. Since I only declared the variable without assigning a value, accessing a at this point would return undefined — meaning “nothing has been defined.”

Then I used a = 1 to store the value 1 in that allocated memory space. From that point on, whenever I access that memory space through the variable a, I get back the stored value 1.

In other words, a variable is essentially a shortcut for accessing a value stored in memory. Without variables, we’d have to use raw memory addresses like 0x0018fa to allocate space, store values, and access them.

If I reassign the variable with a = 2, I’m changing the value stored at memory address 0x0018fa — and that constitutes a state change.

JavaScript provides the let keyword for declaring reassignable variables and the const keyword for non-reassignable ones, giving developers a way to guard against accidentally changing values stored in memory.

So can we maintain immutability simply by never reassigning variables?

Unfortunately not. The way a program loads and uses values from the memory space a variable points to isn’t that simple.

This is where the famous “call by value” and “call by reference” come into play.

Call by Value and Call by Reference

Call by value and call by reference are methods for how variables are passed from one context to another.

This situation of passing variables between contexts is most commonly represented as passing arguments from an outer scope into a function — and in practice, that’s usually the case.

Let’s declare a simple function to explore this further.

function foo (s) {

return str.substring(0, 2);

};The foo function is a pure function that takes a string argument and returns only its first two characters. In other words, foo uses the value it receives as an argument to produce its return value.

Let’s try using foo.

const str = 'Hello, World!';

foo(str);HeSince foo slices the string it receives as an argument, it might look like it’s directly modifying the str variable.

But if you print the str variable that was used as foo’s argument, you’ll find the original value Hello, World! is still intact.

console.log(foo(str));

console.log(str);He

Hello, World!How is this possible? The answer is that the String type — the data type of str — uses “call by value.”

In JavaScript, variables of primitive types like string, number, and boolean all use call by value.

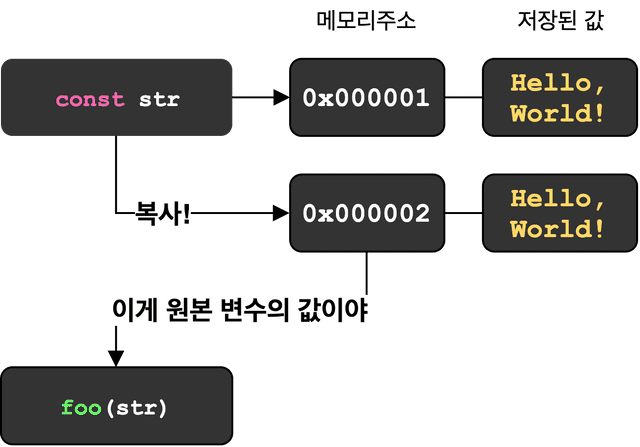

Call by value means that when you pass a variable as a function argument, the value it holds is copied and the copy is given to the function. So instead of passing the value in the memory space that str points to, JavaScript copies that value into a new memory space and passes that instead.

So the value held by str when we called foo(str) and the value accessed through s inside the foo function are stored in completely different memory locations — they’re separate values.

That’s why no matter what foo does to its argument, the original variable is never affected. Even if s is reassigned inside foo, the value in the original variable doesn’t change.

const str = 'Hello, World!';

function foo (s) {

s = 'Reassigned';

return s.substring(0, 2);

}

foo(str);

console.log(str);Hello, World!Even though foo reassigned its argument, the external str variable remained unchanged.

In other words, maintaining immutability isn’t simply about “not modifying function arguments” or “not reassigning variables.” The point is not changing values that are already stored in memory.

On the other hand, objects like Array and Object — which don’t use call by value — behave differently.

This time, let’s declare a simple function that takes an array and pushes the string 'hi' into it, and see what happens.

function bar (a) {

a.push('hi');

return arr;

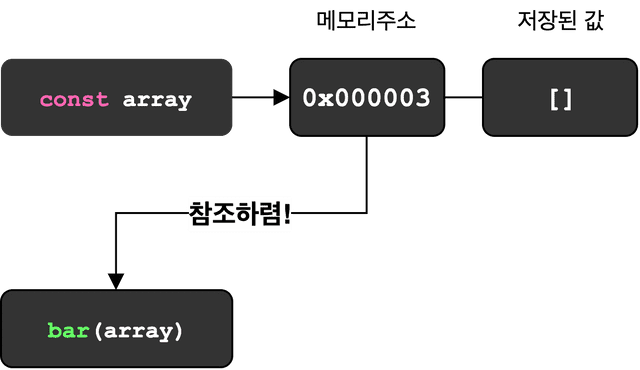

};The primitive str variable uses call by value, but Array — an object — uses “call by reference.” Let’s use the function and check what happens to the original variable.

const array = [];

bar(array);

console.log(array);['hi']Unlike foo, where the original variable was unaffected no matter what the function did to its argument, bar actually changed the array variable’s value.

Unlike call by value — which copies the value into a new space before passing it — call by reference passes “the memory address that the variable points to.”

In other words, the array stored in the memory space that array points to and the array received as bar’s argument are the exact same array stored in the exact same memory space.

Since the array received as bar’s argument is an object that uses call by reference, any modifications to it inside the function modify the original array itself.

In this case, the array stored in memory is directly changed, so we can say state has been mutated — immutability has been broken.

The same act of modifying an argument inside a function leads to vastly different outcomes depending on whether the data type uses call by value or call by reference. If you want to preserve immutability, you must always keep this distinction in mind when writing code.

What Are the Benefits of Preserving Immutability?

Programming while preserving state immutability inevitably means more things to watch out for. But the fact remains that immutability is widely embraced by developers today.

What exactly do we gain by preventing state from changing, and why is everyone so obsessed with immutability?

Preventing Indiscriminate State Changes

State plays a useful role in representing a program’s current situation. But when code everywhere references or modifies state indiscriminately, even the developer can lose track of how the program is behaving.

That’s why developers prefer to impose specific rules and constraints on state mutations — minimizing indiscriminate changes and keeping them trackable.

The most classic situation where indiscriminate state changes cause programs to break is “global variable abuse.” This is exactly why JavaScript conventions recommend banning global variable usage entirely.

let greeting = 'Hi';

function setName () {

name = 'Evan';

}

setTimeout(() => {

greeting = 'Hello';

}, 0);

setName();

console.log(`${greeting}, ${name}`);The greeting variable is a global variable declared in the global scope. The setName function implicitly declares a global variable too, and the setTimeout callback also reassigns the global greeting variable.

In a situation like this, tracking which piece of code changed the global greeting state is nearly impossible. If the console suddenly printed Get out, Evan instead of Hi, Evan, it wouldn’t be surprising at all.

The reason developers end up working overtime in situations like this is, sadly, that it’s not a bug. These are perfectly valid, error-free logic as far as the console is concerned. (An actual error would honestly make debugging easier.)

Using pure functions while maintaining immutability means not accessing external state to modify values already allocated in memory — which defends against these unexpected state changes.

Tracking State Changes Becomes Easy

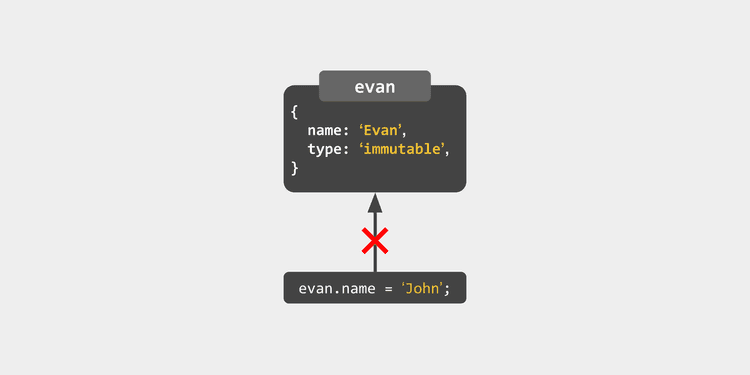

In general, when you need to change an object’s property or an array’s element in JavaScript, immutability inevitably breaks.

After all, when arrays and objects were first conceived, their purpose was to store structured data and maintain and modify state.

const evan = { name: 'Evan' };

evan.name = 'Not Evan'; // State change!But directly modifying values already stored in memory violates the principle of immutability. So a developer who wants to maintain immutability can’t modify object properties or array elements this way.

On top of that — just like the indiscriminate global variable usage we saw — state changes to objects and arrays are equally untraceable. If some rogue code changes an object’s or array’s state and causes a bug, debugging it is no easy task.

But you can’t just ban modifying object properties or array elements either. So how do we solve this?

Let’s look at a simple function that changes an object’s property to understand how state changes occur and how to address them.

function convertToJohn(person, name) {

person.name = 'John';

return person;

}The convertToJohn function takes an object as an argument and assigns the string 'John' to its name property. In other words, this function changes the object’s state.

To state the conclusion upfront: this is not a pure function, because when a function directly modifies a property of an object passed by reference, it also changes the original object outside the function.

const evan = { name: 'Evan' };

const john = convertToJohn(evan);

console.log(evan);

console.log(john);{ name: 'John' } // ?

{ name: 'John' }Someone using convertToJohn might look at the name and think “Oh, this function converts an object into a John object.” But this function was secretly modifying the original object passed as its argument.

The unintended property change is a problem, but the bigger issue is that this state change is completely untraceable. If you compare the evan and john objects above, JavaScript evaluates them as the same object.

The two objects merely have different variable names pointing to the same memory space — they’re actually the same object stored in the same location.

console.log(evan === john);trueIn this situation, the developer is stuck with two nasty problems: “unintended state change” and “untraceable state change.” How can we solve this?

The solution is simpler than you might think — just create a brand new object with name set to 'John'.

function convertToJohn (person) {

const newPerson = Object.assign({}, person);

newPerson.name = 'John';

return newPerson;

}

const evan = { name: 'Evan' };

const john = convertToJohn(evan);

console.log(evan);

console.log(john);{ name: 'Evan' }

{ name: 'John' }The updated convertToJohn no longer directly modifies the person object it receives. Instead, it creates a new object with the same structure using Object.assign, changes the name property to 'John', and returns it.

If this feels too cumbersome, you can use ES6’s spread operator for a more concise syntax.

function convertToJohn (person) {

return {

...person,

name: 'John',

};

}By creating a new object this way, you can prevent unintended state changes and track state changes. Because the object returned by convertToJohn is an entirely new object, separate from evan.

console.log(evan === john);falseWhen changing an object’s state, if you create a “new object with the changed state,” you can use the fact that comparing the previous and next state objects yields false to detect that the object’s state has changed.

This principle is used in React — a UI library for web frontends — to detect state changes. When a developer changes state using methods like setState, React compares the previous and next state using Object.is. If the two objects are evaluated as different, React determines that state has mutated and re-renders the component.

Redux, a state management library, also uses the same principle to detect state changes. That’s why when writing reducers, you shouldn’t directly modify the existing state object’s properties — you must create and return a new object.

function reducer (state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case SET_NAME:

return {

...state,

name: action.payload,

};

// ...

}

}These characteristics of immutability make it easy to detect state changes in reference types, which helps prevent bugs that developers wouldn’t anticipate.

Immutability is also extremely useful in multi-threading scenarios. When multiple threads frantically read and modify a single piece of state, it quickly becomes impossible to tell what value a thread is actually referencing.

It’s like having multiple painters applying paint to a single canvas while trying to complete a picture together. But with proper immutability, it’s more like giving each thread its own canvas, having them paint, and then submit their work.

The developer can detect state changes each time a thread submits its work and can even build logs tracking those changes. How to consolidate the results, or discard unnecessary ones — that becomes a separate concern.

Immutability in Practice

Programming while maintaining immutability is undeniably great for easily tracking and managing state changes. But that doesn’t mean it’s all upside.

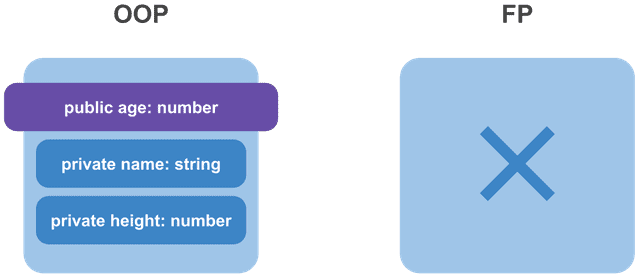

The biggest challenge with immutability is that it’s difficult to integrate with traditional object-oriented programming.

Functional programming’s emphasis on immutability is quite different from the object-oriented programming we’re accustomed to.

OOP uses access modifiers like private to hide state from the outside, giving users a simple interface. Functional programming, by contrast, pursues immutability — not changing program state at all — making program behavior easy to predict and simple.

OOP creates simplicity by hiding mutable state,

OOP creates simplicity by hiding mutable state,while FP creates simplicity by eliminating mutable state entirely

In other words, OOP and functional programming have fundamentally different perspectives on state. OOP is a paradigm focused on “changing state well,” which puts it at some distance from immutability.

Moreover, most APIs and libraries we use today are still designed around OOP, so we can’t fully break free from object-oriented programming.

The problem is that managing OOP-based constructs with immutable principles can be quite costly.

For easier understanding, let’s look at a situation where we create an object using the Web Audio API and need to change its state.

const context = new AudioContext();

let state = {

node: context.createGain(),

};I created a simple object to represent state and assigned a GainNode to it. A GainNode has a gain property that controls audio signal volume, and developers can manipulate the audio signal simply by changing this property’s value.

state.node.gain = 1.2;But directly accessing an object and changing its property violates immutability. To satisfy immutability here, you’d need to create a new gain node object every time you change the gain property.

const setGain = (value) => {

const newGain = context.createGain();

newGain.gain = value;

return newGain;

};

state = {

...state,

node: setGain(value),

};While this preserves immutability and lets you track gain node state changes, it can cause problems when object creation is expensive.

The gain node object provided by the Web Audio API is a full-fledged instance with member variables and methods — it’s not a simple object like { gain: 1 }.

If an instance has many member variables and methods, or if heavy operations are involved in object creation, creating a new object every time a property changes can put significant strain on performance.

You could try copying the existing object, but objects created through constructors require re-linking all prototype chains after copying — which isn’t exactly lightweight compared to copying plain objects. (I’ve actually tried this several times, and the performance was worse than expected.)

Carelessly writing code like this in the name of immutability can severely degrade your entire program’s performance, so wise judgment for each situation is necessary.

Closing Thoughts

Originally, I planned to cover not just immutability but also technical topics like currying using the concept of first-class citizens. But once again, I failed at controlling the length.

It seems that when I write about topics I’m currently passionate about, the content just keeps growing.

While immutability has been getting a lot of attention on the frontend lately, it’s actually not a frontend-exclusive keyword. Immutability originally gained attention as a way to solve the various problems that arise when mutable state is shared across multiple locations.

These problems commonly occurred in concurrent programming scenarios like multi-threading. The traditional approach was to use locks — essentially permissions to access state — where threads could only access state when the lock was released.

But state isn’t limited to one or two variables, and if a lock is set incorrectly and state gets tangled, it’s just as hard for developers to notice. That’s why the concept of immutability — eliminating mutable state entirely — gained traction.

Languages like Erlang and Rust actually enforce immutability far more strictly than JavaScript. If you’re interested in this topic, experiencing those languages might be worthwhile. (I’m thinking about giving Rust a try myself.)

But JavaScript too — due to its characteristically permissive nature — has caused many developers to suffer from unchecked state management since the ES5 era. As web frontend applications grew more sophisticated and demanded complex state management, these concepts became increasingly relevant.

I personally have struggled countless times debugging bugs caused by untraceable state changes, so when I first learned about immutability, I remember following the concept with keen interest.

But as I mentioned, programming with immutability isn’t the right answer for every situation.

I myself naively attached Redux to my toy project — a Web Audio editor — and have been struggling with performance issues due to the object creation costs I described above. (The example I used earlier was from my own experience.)

As I always say, there’s no absolute technology that fits every situation. Rather than claiming immutability is unconditionally good, I believe the right approach is to use immutability through wise decision-making that fits each situation.

This concludes my post: How to Keep State from Changing — Immutability.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Pure Functions – A Programming Paradigm Rooted in Mathematics

Programming/ArchitectureBeyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingFrom State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingMisconceptions About Declarative Programming

ProgrammingHow Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/Architecture