Pure Functions – A Programming Paradigm Rooted in Mathematics

Pure functions: the power to make complex code simple

Following up on my previous post, Functional Thinking – Breaking Free from Old Mental Models, this time I want to talk about “pure functions” — one of the essential concepts you need to understand in order to translate functional programming’s philosophy into actual programs.

Around 2017, as the functional programming paradigm rose to prominence, the concept of pure functions gained attention along with it. Even today, if you search for “pure functions” you’ll find countless posts by developers describing their characteristics.

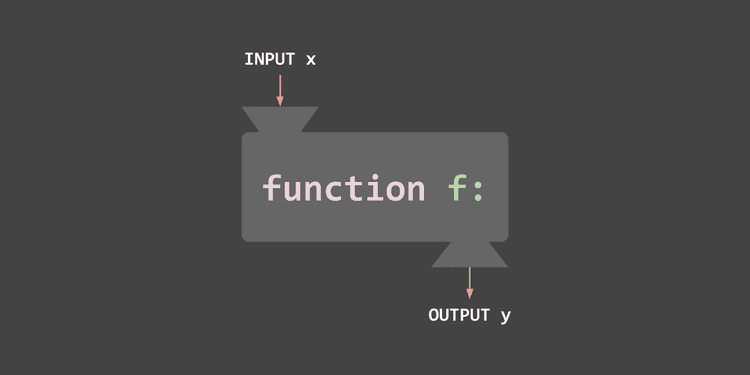

Generally, when studying pure functions, you’ll encounter a definition like this:

- Given the same input (arguments), it must always produce the same output.

- It must not modify external state, nor be affected by external state.

But learning it this way makes it easy to just memorize “pure functions are functions with these characteristics” — when in reality, pure functions are a much simpler concept that doesn’t need to be approached this way.

Sure, just memorizing these traits is perfectly fine for understanding and using pure functions. But I want to dig a bit deeper into where these characteristics come from and what pure functions actually mean at a fundamental level.

Pure Functions Are Just Mathematical Functions

We give them the special name “pure functions” and study their characteristics as if they’re something novel, but pure functions are really nothing more than mathematical functions faithfully implemented in the programming world.

The Wikipedia definition of functional programming gives a more detailed explanation of this concept:

Functional programming is a programming paradigm that treats computation as the evaluation of mathematical functions and avoids changing-state and mutable data. In contrast to imperative programming, which emphasizes changes in state, functional programming emphasizes the application of functions.

Functional programming - Wikipedia source

The most important keyword in this definition is “mathematical functions.” The thing we study by memorizing various characteristics is literally a pure function — that is, a function as used in mathematics.

Because we use the concept of “function” in both mathematics and programming, we sometimes forget that programming functions are actually quite different from their mathematical counterparts.

So let’s revisit the definition of mathematical functions to understand the differences between mathematical and programming functions.

Functions in Mathematics

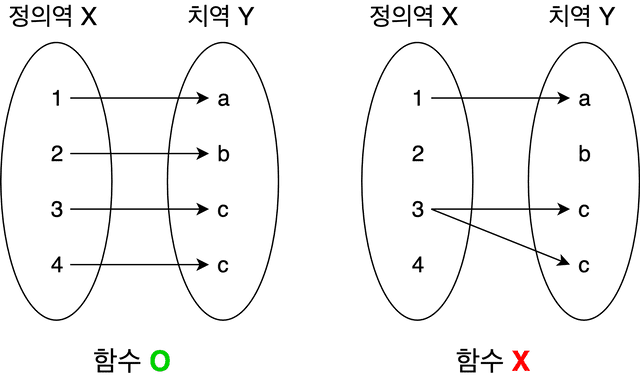

The concept of a function that we learned in middle school has roughly the following definition:

For any , there uniquely exists a corresponding

It uses the intimidating syntax typical of mathematics, but it’s really not complicated. In this definition, is called the domain and is called the range — think of the domain as the set of possible inputs to the function and the range as the set of possible outputs.

In other words, the domain contains the values used as function arguments, and the range contains the values produced as results.

But the most important part of this definition isn’t the domain or range — it’s the concept that for each input value, the corresponding output value uniquely exists.

When you give a value to a function, it must return exactly one value. That is the original definition of a function.

As shown in the right diagram, if a domain element has no corresponding range element

As shown in the right diagram, if a domain element has no corresponding range elementor has two or more, it no longer satisfies the definition of a function

For easier understanding, consider a simple function that multiplies its argument by 2. We express this as .

If we set to 1, we get . If one day suddenly equaled 3, then the function would no longer have a unique range element corresponding to a specific domain element — and it could no longer be called a function.

The characteristics commonly attributed to pure functions originate from these very properties of mathematical functions.

Functions in Programming

But functions in programming have no such constraints. Without even getting into elaborate examples — don’t we have void functions that return nothing at all?

function foo (x: number): void {

const y = x * 2;

alert(y);

}

console.log(foo(1));undefinedFrom the perspective of mathematical functions, a void function is not a function. There’s no range element corresponding to the domain element x. That’s why we say the concept of a function in programming differs somewhat from its mathematical counterpart.

In truth, programming functions merely borrowed the idea of “you give it a value and it computes something” from mathematical functions. From a mathematical standpoint, programming functions are more often not functions than they are.

Most importantly, the biggest difference between mathematical functions and programming functions is that a programming function’s behavior can be inconsistent.

The mathematical function from earlier is guaranteed to always return 2 when given 1 as input, regardless of its internal implementation. But in programming, you can easily create functions that don’t behave this way.

Think of functions that use methods like Math.random or Date.prototype.getTime. These methods produce values that have nothing to do with the function’s logic, so if a function’s computation depends on them, the developer can never predict what value the function will return.

function sum (x: number): number {

return x + Math.random();

}

sum(1);

sum(1);

sum(1);5 // ?

4 // ?

9 // ?These kinds of concepts exist only in the programming world, where values with specific meanings can be stored, assigned, and retrieved. In mathematics, such concepts simply don’t exist.

We call these values with specific meanings “state.” State plays a useful role in representing a program’s current situation, but when code everywhere references or modifies state indiscriminately, even the developer can lose track of how the program is behaving.

That’s why developers prefer to impose specific rules and constraints on state mutations — minimizing indiscriminate state changes and making changes trackable.

The problem is that programming functions frequently develop entanglements with state — more precisely, with state outside the function. Here’s a simple function called addState that takes a number and adds it to a variable declared outside the function.

let state = 3;

function addState (x: number): number {

return state + x;

}

addState(1);4The addState function references an external value called state and adds it to its argument. In other words, this function’s return value is dependent on the external state variable state — a situation that can make it impossible for developers to predict the function’s behavior.

If state gets modified somewhere else, things get even messier.

state = 10;

addState(1);11We called the same function with the same argument, but got a completely different result. Because this function’s return value changes with external state, the developer simply cannot predict its behavior.

When a function is affected by external state or directly modifies external state, we call this a “side effect.” Functions that produce side effects are one of the risk factors that cause bugs developers can’t anticipate.

For this reason, languages like JavaScript have conventions that discourage declaring and assigning global variables, and React Hooks provides a useEffect hook specifically to separate side-effect-producing operations.

function TestComponent () {

useEffect(() => {

localStorage.setItem('greeting', 'Hi');

return () => {

localStorage.removeItme('greeting');

};

});

return <div>TestComponent</div>;

}This is a simple function in a contrived scenario, so it might look artificial. But in real applications, there are plenty of functions doing far more complex and bizarre things.

For instance, a simple function that returns the result of communicating with an API server is also a type of impure function.

async function getUsers () {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/users');

return response.json();

}

catch (e) {

throw e;

}

}It’s obvious that getUsers won’t return the same value every time it’s called. The user list can change depending on the current database state.

Because impure functions make it impossible for developers to predict results, writing tests to verify their behavior is also impossible. How do you test something when you can’t even guess what it’ll output?

As you can see, functions in the programming world have far more variables than mathematical functions and are much harder to predict.

Returning to Pure Mathematical Functions

Now that we’ve examined the differences between mathematical functions and programming functions, let’s revisit the definition of pure functions:

- Given the same input (arguments), it must always produce the same output.

- It must not modify external state, nor be affected by external state.

As I discussed, in mathematics, a function simply takes an input, performs some calculation, and produces exactly one result.

And since mathematics has no concept of state — values that can be stored, assigned, and retrieved — there can obviously be no such thing as a side effect where a function interacts with external state.

In other words, when you apply mathematical functions directly to programming, the pure function properties — “a function’s result is determined only by its arguments” and “a function must not modify or be affected by external state” — are naturally satisfied.

And the immutability that functional programming talks about is also rooted in mathematics. Since pure functions implement mathematical functions — which have no concept of state — the concept of mutating state shouldn’t exist either.

But because state undeniably exists in the programming world, we explicitly define and uphold constraints like “you must not directly modify a function’s arguments.”

The advantages that come with using pure functions — “testing becomes easier” and “referential transparency is guaranteed” — are also completely obvious when you think about mathematical functions.

As I briefly mentioned, writing unit tests for a function that returns different values each time is truly hopeless. Since the developer can’t predict the function’s behavior, they can’t provide a correct answer to test against — making test writing impossible.

And the claim that pure functions guarantee referential transparency is really nothing special once you consider what the = sign means in mathematics.

doesn't change the computation's outcome — and we've been using this concept in math all along

Pure functions let you predict what result you’ll get for any given arguments, and because they eliminate the concept of state entirely, they make it easier for developers to build predictable applications.

Furthermore, since a pure function focuses solely on its own computation regardless of external state, a pure function declared in one application is guaranteed to behave identically when transplanted to another. This aligns with one of the key conditions for good modularization: “high cohesion.”

Applications built with pure functions are easier for developers to understand in terms of both structure and behavior. So even outside the functional programming paradigm, pure functions are a concept that meaningfully benefits overall application design.

Closing Thoughts

When I first encountered the concept of pure functions, I learned about their characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages through Google searches and blog posts by other developers. At the time, my reaction was “Great, yet another thing to study.”

When you first encounter a paradigm like pure functions, you instinctively turn to Google to gather information. Most of the time, you end up studying from posts that other people have written.

But studying this way, I found that I often learned a few characteristics and pros and cons first, without deeply understanding the fundamental reason or principle behind the paradigm.

So I initially received pure functions as “something new I need to study.” But when I later thought about it carefully and realized it was simply the mathematical concept of a function — something I’d learned as a kid — implemented in programming, I remember feeling a bit anticlimactic.

That’s exactly why I didn’t explain pure functions in this post as “functions with such-and-such characteristics.” This is just my personal view, but since most people already learned the definition and concept of functions in school, I thought approaching it through the lens of “mathematical functions” would actually lead to faster understanding.

Anyway, what I wanted to convey through this post is that pure functions are not a novel concept at all — they’re something anyone who went through basic math education should find familiar.

Of course, how to design programs using pure functions isn’t covered in school curriculum and requires separate study. But at least understanding pure functions and immutability — key concepts in functional programming — shouldn’t be all that difficult.

In the next post, I plan to discuss “immutability” — another important concept in functional programming alongside pure functions.

This concludes my post: Pure Functions — A Programming Paradigm Rooted in Mathematics.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

How to Keep State from Changing – Immutability

Programming/ArchitectureBeyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingFrom State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingMisconceptions About Declarative Programming

ProgrammingHow Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/Architecture