Functional Thinking – Breaking Free from Old Mental Models

From imperative to declarative: how to shift the way you think about programming

Recently, more and more languages have been adopting the functional programming paradigm, and developer interest has been rising steadily along with it. I remember becoming deeply curious about functional programming — a paradigm that felt so different from what I was used to — after reading the book Functional Thinking.

A cute little squirrel book I've read multiple times because it's so enjoyable

A cute little squirrel book I've read multiple times because it's so enjoyable

Of course, reading this book alone doesn’t make you fluent in functional programming. Concepts and techniques like currying, monads, and higher-order functions can become familiar with dedicated study and practice, but as I mentioned, truly designing programs with any paradigm requires fundamentally changing the way you think.

For that reason, this post won’t focus on specific functional programming skills. Instead, I want to talk about why functional programming has gained so much attention, and what concepts this paradigm uses to view and structure programs.

Why Should I Learn Functional Programming?

Honestly, object-oriented thinking and imperative programming are more than enough to design and write most programs. We’ve been building massive programs with these approaches for decades, haven’t we?

But functional programming is attracting so much attention because it clearly differs from those approaches — and those differences allow developers to be more productive.

So what exactly about functional programming has won developers over?

Different developers will have different reasons, but the key advantages I’ve personally felt are these:

- It provides a high level of abstraction

- Code reuse at the function level is easier

- By favoring immutability, program behavior becomes more predictable

You’ll likely find similar points highlighted in other blog posts and books on functional programming.

Among these advantages, immutability is less a benefit of functional programming itself and more a natural consequence of using pure functions. I’ll save that discussion for when I cover pure functions in detail. For this post, I want to focus on the keywords “high-level abstraction” and “function-level reuse.”

A High Level of Abstraction

Fundamentally, functional programming is a paradigm that implements the characteristics of declarative programming through compositions of functions. And one of the hallmark advantages of declarative programming is that it provides a higher level of abstraction than the methods used in imperative or object-oriented programming — allowing developers to focus solely on solving the problem at hand.

To understand what this “high level of abstraction” that declarative programming offers really means, and what its pros and cons are, we first need a clear understanding of the concept of abstraction itself.

What Abstraction Really Means

If you’re familiar with object-oriented programming, you might describe abstraction as the act of extracting and organizing the characteristics of something that exists in the real world. That’s not wrong, and when you’re first learning OOP, thinking about it this way is perfectly fine.

But the fundamental meaning of the word “abstraction” covers a much broader range of concepts than simply defining a class from an object’s characteristics.

At its core, abstraction is about making the complex things that underlie some task appear simple. The act of abstracting an object into a class definition in OOP is, fundamentally, consistent with this definition.

Consider a Human class that has a name and can introduce itself. Let’s create an object from it and call its method.

class Human {

private name: string = '';

constructor(name: string) {

this.name = name;

}

public say(): string {

return `Hello, I am ${this.name}.`;

}

}

const me = new Human('Evan');

console.log(me.say());Hello, I am Evan.There’s an important fact here. Because we usually create both the class and the object ourselves, it’s easy to overlook — but even if you had no idea how the Human class was implemented, you could still create an object from it and use its methods without any problem.

As long as you know what functionality the class exposes to the outside world, you can create objects and call methods to get the behavior you want.

interface {

constructor: (string) => Human;

say: () => string;

}In object-oriented programming, we use access modifiers like public and private to expose only what we want to — a technique called encapsulation — in order to provide users with a high level of abstraction.

Beyond classes, the libraries we commonly use are also a form of abstracted modules.

If we had to fully understand the implementation source of a library like React or RxJS before we could use it, things would be incredibly difficult. But we don’t need to examine every line of a library’s source code — as long as we read the official documentation to understand its features, we can use it just fine. (The catch is that using it well does require reading the source.)

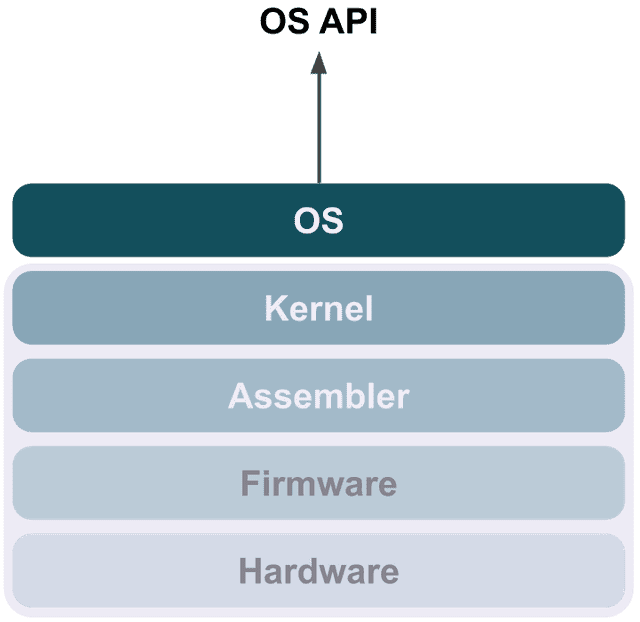

And the OS APIs and browser APIs we use when writing programs are also a kind of abstracted feature list. Thanks to these abstracted lists, as long as we know what each API does, we can comfortably issue commands to the computer without dealing with low-level operations directly.

If you’re not a developer, think about the everyday programs you use.

For example, imagine you’re using Photoshop to convert a color photo to black and white. Photoshop performs complex image processing operations under the hood, but thanks to its various features, we can focus solely on the act of editing the photo.

In reality, converting a color photo to black and white requires iterating through the pixel data — a matrix of values — and averaging the RGB values, among other steps. But because all that complex, tedious work is abstracted away, the user simply needs to click “Image > Adjustments > Desaturate.”

In short, abstraction means taking something complex and distilling it down to its core concepts or features to make it simple. When a program is well-abstracted, the user can comfortably use its features without knowing what lies beneath their layer of abstraction or how it works.

Is a Higher Level of Abstraction Always Better?

As we just discussed, abstraction is the act of making something complex appear simple. A higher level of abstraction means the act of simplification itself has become more sophisticated.

In that sense, a higher level of abstraction is certainly more convenient for users. For those who aren’t sure what “more convenient” means here, let me use programming languages as an example.

When building a program, we could use machine code made of 0s and 1s, or assembly, or a high-level language close to natural language like Java.

If you grabbed a random developer off the street and asked “Would you rather code in machine code or assembly?”, almost no one would pick machine code. Machine code is barely abstracted at all — practically raw — making it extremely difficult for humans to understand.

And if you asked “Assembly or Java?”, very few would choose assembly either. In this case, assembly has a much lower level of abstraction compared to Java, so coding in Java is simply more comfortable for humans. This is a textbook example of the difference in abstraction levels.

Writing a large program in assembly means the developer has to manage an enormous number of details, but with Java, you can use syntax like for and if along with various APIs, programming more comfortably than in assembly. All the tedious work of allocating values to memory, gathering them in registers, and pulling them back out is handled by the JRE (Java Runtime).

This pattern of newer technologies providing higher levels of abstraction and greater convenience isn’t something that started with functional programming — it’s been an extremely common occurrence throughout the history of computer science. As technology advances and raises the level of abstraction, we become capable of building increasingly complex programs.

However, a high level of abstraction isn’t all upside. Whenever a technology touts high abstraction as an advantage, there’s a strong chance it will face criticism like “the performance is bad” or “how are you supposed to optimize when everything’s abstracted away?” The poster children for this kind of controversy are Java and garbage collectors. (And assembly, for that matter…)

John von Neumann (1903–1957)

John von Neumann (1903–1957)The man who said we shouldn't waste computer performance on things like assembly

Java’s great strength was that using bytecode and the JVM (Java Virtual Machine), you could write code once and have it run on any OS. Compared to earlier languages that were tied to specific operating systems or CPUs, the level of abstraction had risen significantly. But when Java first came out, it was heavily criticized for being too slow compared to C to be practical.

Garbage collectors, too, provide the convenience of not having to manually allocate and free memory. But they come with their own issues: performance costs from constantly tracking when to free objects, the difficulty of knowing exactly when an object is freed from memory, and problems like the inability to free circular references when using reference counting. They don’t always work perfectly.

That said, not many people would actually prefer to use C and manually manage memory in an environment where Java and garbage collection are available. These high-abstraction technologies exist and thrive precisely because modern machines can cover the performance costs to a reasonable degree.

Functional programming, as a paradigm that pursues a high level of abstraction, does come with some performance trade-offs. In fact, the concept of abstracting programs at the function level has been around since LISP was introduced in 1958, but back then, such concepts probably felt like a luxury. When memory was so scarce that even a single task was a struggle, who had room for abstraction?

But today’s machines are performant enough to comfortably handle the level of abstraction that functional programming demands, so performance concerns feel largely irrelevant.

And if you’re writing a program where performance truly matters, you don’t have to insist on functional programming. There’s no single “correct” paradigm anyway. Just as people still use C or assembly for optimization today, functional programming is best used judiciously, in the right situations.

Now, to see what form functional programming’s high-level abstraction actually takes, let’s compare imperative programming — the paradigm we’re already familiar with — against declarative programming, the parent concept of functional programming.

Imperative and Declarative Thinking Are Fundamentally Different

Imperative programming means explicitly telling the computer how to solve a problem, step by step. Declarative programming means focusing on what to solve, and delegating the how to the computer.

From the earliest days of programming until relatively recently, we’ve primarily used imperative programming — explicitly commanding the computer. Functional programming, however, is a form of declarative programming: it focuses more on the problem to solve and hands the mundane details off to the computer.

Because declarative programming delegates trivial tasks to the computer, the keyword “high-level abstraction” inevitably follows. If the abstraction level were low, the developer would have to manually control every one of those trivial tasks.

Let’s compare how imperative and declarative programming solve a problem, and examine the difference in abstraction levels between the two paradigms. Here’s our problem:

const arr = ['evan', 'joel', 'mina', ''];Iterate through the array, filter out empty strings, and capitalize the first letter of each element.

How Do We Solve It? (Imperative Programming)

Imperative programming is literally about giving the computer detailed instructions on how to perform the task. More precisely, it’s about issuing step-by-step commands to build your way toward the result you want.

Since most working developers today started learning to code with the traditional imperative paradigm, this approach feels natural to many of us — myself included.

When most developers encounter this kind of problem, they’ll think of using a loop like for to sequentially traverse and process the array elements.

const newArr = [];

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i].length !== 0) {

newArr.push(arr[i].charAt(0).toUpperCase() + arr[i].substring(1));

}

}Writing code that repeats an action using a for loop is so familiar to developers that we could do it with our eyes closed — but that very familiarity makes us overlook just how many instructions are packed into this short piece of code.

Here’s roughly what I was thinking when I wrote the code above:

- Initialize variable

ito0- If

iis less than the length ofarr, execute the loop body- After each iteration, increment

iby1- Access the

ith element ofarr- If the element’s length isn’t

0, capitalize its first letter- Push the resulting string into the

newArrarray

My thought process while writing the code maps exactly to the commands I need to give the computer.

In other words, I have to manually manage the state of i, keep track of which index I’ve traversed by incrementing i each loop, access array elements directly using i, and check whether each element is an empty string.

This approach — issuing granular commands to the computer to build toward your desired result — is what we call imperative programming.

Now let’s revisit the problem we need to solve:

Iterate through the array, filter out empty strings, and capitalize the first letter of each element.

Can you read through those commands and immediately picture this problem? Since this particular problem is simple, you might. But for something more complex, you’d probably need to read through it several times and maybe sketch a diagram.

In other words, imperative programming is closer to how computers think than how humans think, so it’s not exactly human-friendly. That’s why developers practice this kind of thinking through exercises like algorithm problems.

So what does the same task look like in declarative programming?

What Are We Solving? (Declarative Programming)

Declarative programming, by contrast, feels more like telling the computer “I want to do this!” You delegate the tedious work to the computer and focus only on what needs to be done to solve the problem.

Functional programming, then, is a paradigm that implements this declarative approach through functions. Let’s solve the same problem using declarative programming.

Iterate through the array, filter out empty strings, and capitalize the first letter of each element.

function convert(s) {

return s.charAt(0).toUpperCase() + s.substring(1);

}

const newArr2 = arr.filter(v => v.length !== 0).map(v => convert(v));The filter method here iterates through the array and produces a new array containing only the elements for which the callback returns true. The map method iterates through the array and produces a new array using the callback’s return values.

Here’s what I was thinking when I wrote this code:

- Declare a function that capitalizes only the first letter of a given string

- Filter

arrto keep only elements whose length isn’t 0- Iterate through the filtered array and use the function from step 1 to capitalize each element’s first letter

We wrote code that performs the same task, but the flow of thought is noticeably different. Internally, it’s handled similarly to the imperative approach, but at least I no longer have to think about declaring and managing an index variable.

And more importantly, my thought process now closely mirrors the problem itself:

Iterate through the array, filter out empty strings (filter), and capitalize the first letter of each element (convert + map).

Declarative programming focuses on letting the developer concentrate on the essence of the problem. And functional programming is simply the implementation of this declarative paradigm through functions.

But delegating trivial control to the computer isn’t all upside. The classic trade-off here is the “performance” issue I mentioned when discussing abstraction.

When I used imperative programming to perform these tasks, I did everything inside a single loop. But the declarative version has filter and map each iterating through the entire array, which can result in a performance penalty.

Even though modern machines are powerful enough to handle this level of abstraction, if you had a billion elements to process, this kind of difference could have a significant impact on overall program performance. That’s why I said functional programming should be used judiciously, in the right situations.

Programs Made of Objects vs. Programs Made of Functions

So far, we’ve looked at the difference in thinking between imperative and declarative programming.

As I mentioned, functional programming implements the declarative paradigm through collections of functions and their composition, so it’s frequently compared not just to imperative programming but also to object-oriented programming, which defines programs as collections of objects and their relationships.

Just as I said when discussing imperative and declarative programming, there’s no hierarchy between OOP and functional programming. Each simply has different strengths and weaknesses.

So what advantages does functional programming offer over object-oriented programming?

There are many pros and cons, of course, but I personally believe the biggest advantage is that code reuse at the function level becomes much easier.

Thinking in Smaller Pieces

A developer accustomed to object-oriented programming will, upon hearing a set of requirements, immediately picture object blueprints in their head. They then define the relationships between these objects to lay the foundation for a large program.

In OOP, an object — composed of member variables (state) and methods (behavior) — is the smallest unit of a program. When using OOP, we can’t design with anything smaller than an object.

When we use OOP, we define an object’s state and behavior through a class — a kind of blueprint that serves as an abstraction of the object.

class Queue<T> {

private queue: T[] = []; // Internal state

// Queue behavior expressed as methods

public enqueue(value: T): T[] {

this.queue[this.queue.length] = value;

return this.queue;

}

public dequeue(): T {

const head = this.queue[0];

const length = this.queue.length;

for (let i = 0; i < length - 1; i++) {

this.queue[i] = this.queue[i + 1];

}

this.queue.length = length - 1;

return head;

}

}const myQueue = new Queue<number>();

myQueue.enqueue(1);The Queue class holds an internal array as its state and implements queue operations — adding and removing elements. The private access modifier prevents external code from directly accessing and modifying the internal queue array, bypassing the class’s methods.

This works perfectly fine for everyday programming. But what if I now want to create a Stack class?

Intuitively, it seems like I could reuse the dequeue operation as-is and just reverse the enqueue behavior to get a working stack. But the only way to take a method already implemented inside one class and use it in another class as if it were its own is through inheritance — and creating a Stack that inherits from Queue would start tangling the relationships between objects.

In other words, because the smallest unit of abstraction and reuse in OOP is the “object,” it becomes difficult to break things down any further. But in functional programming, instead of focusing on objects representing queues or stacks, we focus solely on the operations these structures use to handle data.

- An operation that adds an element to the tail of an array (push)

- An operation that removes an element from the head and shifts the remaining elements forward (shift)

Using JavaScript’s built-in methods push and shift, we can perfectly implement queue behavior without declaring any classes or objects, and without writing out queue operations imperatively as I did above.

And if we want to additionally implement a stack, we can use shift to remove elements and unshift instead of push to add them.

const queue: number[] = [1, 2, 3];

queue.push(4);

const head = queue.shift();

const stack: number[] = [1, 2, 3];

stack.unshift(0);

stack.shift();This might seem obvious, but this is the fundamental advantage of composing programs from functions rather than objects. The scope over which you can reuse elements becomes much wider.

However, when you reuse small functions across a wide scope, program complexity can grow quickly. To defend against this, functional programming imposes several constraints: functions shouldn’t modify values outside themselves, and a function given the same arguments should always return the same result.

Functions with these constraints are called “pure functions.” When explaining pure functions, the description usually ends up as “functions with a few constraints” — but fundamentally, they’re nearly identical to the concept of functions in mathematics.

Functions in computer science did originate from mathematical functions, but because the two disciplines have pursued different goals and evolved along different paths, the concept of “function” shares only the name — they’re actually quite different in practice. Pure functions, then, are about returning to the original essence of mathematical functions to reclaim simplicity.

For that reason, I personally find it easier and faster to understand pure functions from a mathematical perspective rather than a programming perspective.

Since the topic of this post is more about the advantages and characteristics of thinking in functions rather than functional programming itself, I’ll save the discussion of pure functions and immutability for a future post where I cover functional programming’s features and techniques in more detail. (That topic is surprisingly fun, too.)

Closing Thoughts

Until recently, I wasn’t deeply interested in functional programming. I thought imperative programming and object-oriented thinking were sufficient to design most applications.

But that was simply because the first paradigms I learned in school were imperative and object-oriented programming — they were ingrained in my muscle memory. Being able to wield any paradigm freely means you’ve already internalized its way of thinking, so adopting a new design pattern or paradigm means breaking those existing mental models.

Personally, I find changing the way you think far more difficult than learning techniques like currying, higher-order functions, or monads. To be honest, even now — after studying functional programming and opening my mind to it — when I hear a set of requirements, I still instinctively reach for imperative and object-oriented approaches first.

But as I’ve said multiple times in this post, functional programming doesn’t replace object-oriented or imperative programming, nor is there any hierarchy among these paradigms. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and you simply pick the right one for the situation.

Moreover, many libraries are still designed around object-oriented concepts, and their usage patterns involve creating objects with member variables and methods. Integrating these libraries with your program often makes it more convenient to design the overall architecture in an object-oriented style — and that’s a perfectly valid consideration.

For example, Redux — a popular state management library in the JavaScript ecosystem — detects state changes based on pure functions and immutability. I’ve personally struggled quite a bit trying to manage AudioNode object states with Redux in a toy project using the Web Audio API.

That said, the advantages functional programming brings — its high level of abstraction and finer-grained code reuse — clearly help when building complex programs. Ultimately, being good at functional programming isn’t just about deeply understanding the paradigm — it also means being able to judge which situations it’s best suited for.

In the next post, I plan to cover essential functional programming concepts like pure functions, immutability, and lazy evaluation, along with various techniques used to reduce program complexity.

This concludes my post: Functional Thinking — Breaking Free from Old Mental Models.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

From State to Relationships: The Declarative Overlay Pattern

ProgrammingMisconceptions About Declarative Programming

ProgrammingBeyond Functors, All the Way to Monads

ProgrammingHow Can We Safely Compose Functions?

Programming/ArchitectureHow to Keep State from Changing – Immutability

Programming/Architecture