TCP's Flow Control and Error Control

How TCP delivers packets safely — a guide to flow control and error control

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) has built-in features for controlling the flow of transmitted data and detecting and responding to network congestion.

If TCP didn’t provide these features, developers would have to manually define what units to send data in, and handle exceptions when packets are lost. Thanks to TCP handling all of this, we can focus entirely on application-layer behavior.

TCP’s transmission control methods are generally divided into three categories: flow control (regulating the amount of data being transmitted), error control (handling lost or corrupted data during communication), and congestion control (responding to network congestion).

Of course, application-layer developers rarely need to touch transport-layer protocols like TCP directly. But if something goes wrong at this level, not understanding how TCP works means you won’t even be able to identify the cause, let alone fix it. (And overtime will inevitably follow.)

With that in mind, this post covers TCP’s flow control and error control techniques.

TCP’s Flow Control

When a sender and receiver exchange data, various factors can cause their processing speeds to differ. If the receiver processes data faster than the sender transmits it, there’s really no problem.

It handles everything as fast as it comes in. The issue arises when the sender is faster than the receiver.

Both the sender and receiver have buffers for storing data. If the sender transmits data faster than the receiver can process what’s in its buffer, the receiver’s buffer will eventually fill up.

It's like pouring water into an already full glass

It's like pouring water into an already full glass

Data that arrives when the receiver’s buffer is full gets discarded — there’s simply no room left. The sender would of course resend the data, but since data transmission is highly variable depending on network conditions, it’s best to minimize this kind of retransmission whenever possible.

So the sender needs to gauge the receiver’s processing speed and decide how fast and how much data to transmit. This is TCP’s flow control.

The receiver includes its window size — representing how much data it can handle — in its response header and sends it to the sender. The sender then references this window size and current network conditions to send an appropriate amount of data, thereby controlling the overall flow.

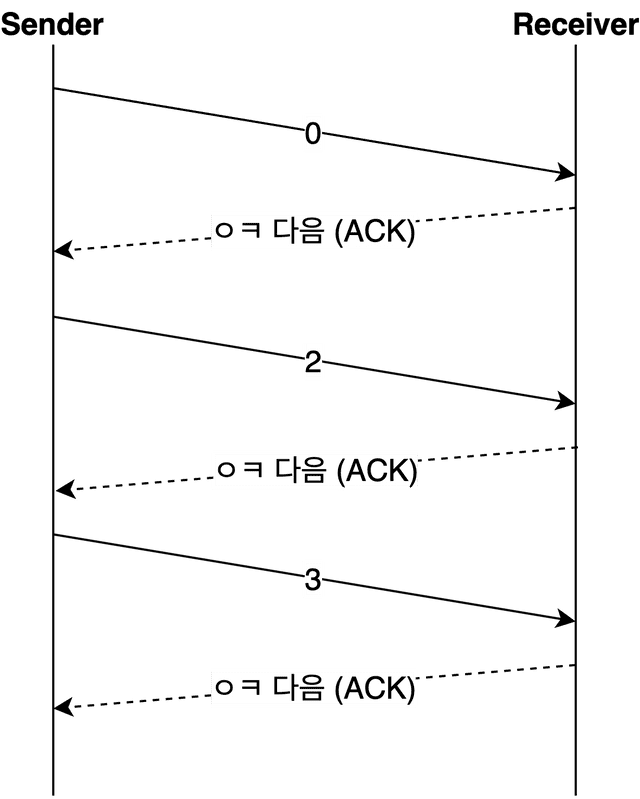

Stop and Wait

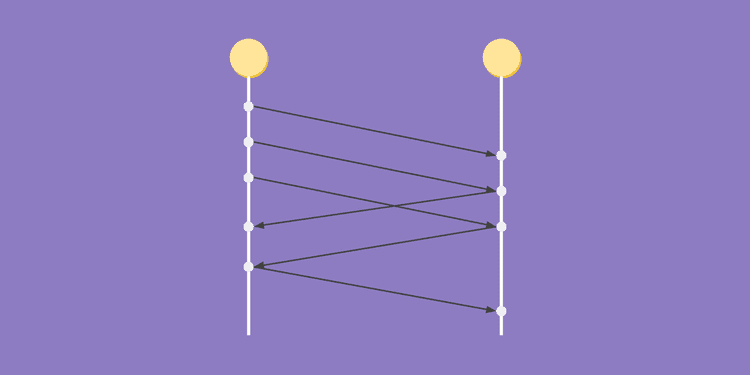

Stop and Wait is a general term for any approach where, after sending data, you wait for a confirmation response before sending more. The receiver can reply with things like “got it!” or “didn’t get it…” — and the type of response determines which error control methods can be used.

The core principle of Stop and Wait flow control is simply “send data when the other party responds,” making it straightforward to implement and easy for developers to understand.

If you think about implementing basic ARQ (Automatic Repeat Request), you could set the receiver’s window size to 1 byte and use something like can process = 1, cannot process = 0 — a rough implementation that would still work.

But an approach that only exchanges “can process” or “cannot process” signals is as inefficient as it is simple. The sender can only find out whether the receiver can handle data by actually sending it. In other words, this basic Stop and Wait approach essentially amounts to just keep sending until it works.

For this reason, when using Stop and Wait for flow control, various error control methods are introduced alongside it to compensate for this inefficiency.

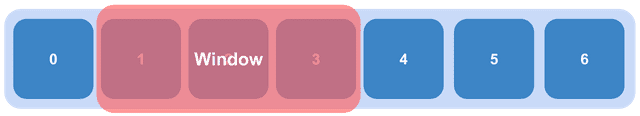

Sliding Window

As we just saw, Stop and Wait has efficiency issues, so modern TCP uses the sliding window approach in almost all cases unless there are special circumstances.

Sliding window works by having the receiver define how much data it can process at once, and continuously informing the sender of its current processing status to control the data flow.

While there are many differences from Stop and Wait, the biggest one is that the sender knows how much data the receiver can handle. With this information, the sender can roughly predict whether data will be processed without the receiver having to explicitly respond “can process” to each piece.

Both the sender and receiver have buffers for storing data, plus a separate masking tool called a window. The sender can continuously transmit data within this window without waiting for the receiver’s response.

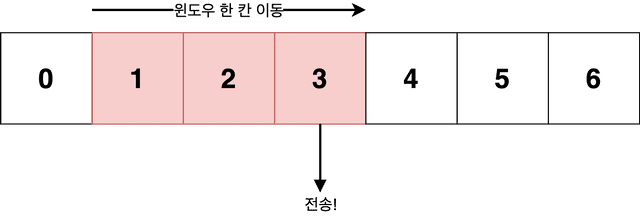

Frames within the window can be sent continuously without waiting for the receiver's response

Frames within the window can be sent continuously without waiting for the receiver's response

The sender’s window size is determined during the 3-way handshake when the TCP connection is first established. During this process, both sides inform each other of their current buffer sizes, and the sender uses the receiver’s buffer size to determine its own window size through a process of “hmm, they can probably handle about this much.”

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [S], seq 1487079775, win 65535

localhost.receiver > localhost.initiator: Flags [S.], seq 3886578796, ack 1487079776, win 65535

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [.], ack 1, win 6379Observing the 3-way handshake via tcpdump, you can see that the initial SYN and SYN+ACK packets each report their own buffer sizes, and in the final ACK packet the sender announces its chosen window size.

Both sides reported their buffer size as 65535, but the sender’s final window size is 6379. Why did the sender set its window to one-tenth of the receiver’s buffer?

The sender’s window size isn’t determined by the receiver’s buffer size alone — it considers various other factors as well. The network is too unpredictable to simply trust the buffer size the other party reported. A key value used here is RTT (Round Trip Time), representing the round-trip time of packets.

The sender measures the time between sending its initial SYN packet and receiving the SYN+ACK response, using this to infer the current network conditions. If this value is too large, it means the round trip is slow, suggesting poor network conditions, so the sender reduces its window size.

This window size isn’t fixed — it can change dynamically throughout the communication based on network congestion and the window sizes the receiver reports. By adjusting the window size (the amount of data sent continuously), TCP can flexibly control the flow.

Now that you have a general understanding of windows, let’s see why this technique is called sliding window.

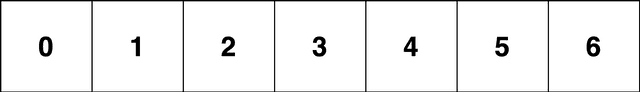

Imagine the sender wants to transmit data with sequence numbers 0 through 6. The sender’s buffer would contain the data to be transmitted like this:

The sender considers the receiver’s window size and current network conditions, sets its window size to 3, and starts transmitting the data within the window.

What state is the data in the window? It’s been sent, but the sender hasn’t yet received confirmation from the receiver.

In other words, data in the window is always in a state of “sent, but don’t know if the other party has processed it.” There could also be situations where data is placed in the window but blocked and can’t be processed, but let’s keep things simple and not worry about those cases.

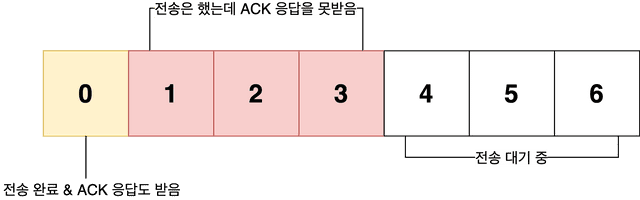

The receiver then processes data at its own speed and responds with the amount of remaining space in its buffer. If the receiver sends back Window Size: 1, it means “I have 1 byte of buffer space left, so only send that much more.”

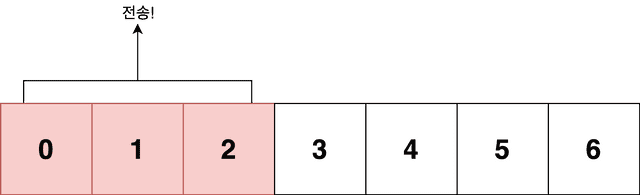

Now the sender knows it can send one more piece of data, so it slides its window one position over and transmits the newly included data (number 3) to the receiver.

Because the window moves sideways to include new data for transmission, it’s called a sliding window. If the receiver had sent a window size larger than 1, the sender would slide its window further and send more data continuously.

However, since the sender’s window size is 3, even if the receiver reports 4, it won’t slide 4 positions — only up to its own window size of 3. But in this case, the sender would recognize that the receiver’s performance has improved and could respond by increasing its own window size.

The sender’s buffer can be roughly divided into three states:

In short, the sliding window approach repeats the cycle of “send → receive response → slide window,” continuously transmitting as much data as currently possible.

This simplified diagram with only numbers 0 through 6 might not seem impressive, but TCP’s maximum window size without any options is 65,535 bytes, and with the WSCALE option maxed out, it can be set to 1 GB.

Plus, the data sent continuously in one batch isn’t just one or two pieces — it’s often hundreds of bytes at a time. In real-world environments, this delivers significantly better efficiency compared to Stop and Wait flow control. Theoretically, up to 1 GB can be transmitted continuously without a single ACK response from the receiver.

Because the sliding window approach is clearly faster in terms of transmission speed compared to Stop and Wait’s one-at-a-time send-and-wait cycle, and because the window size can be flexibly adjusted through ongoing communication between sender and receiver, modern TCP uses sliding window for flow control by default.

TCP’s Error Control

TCP fundamentally uses ARQ (Automatic Repeat Request) — retransmission-based error control. In plain terms, if something goes wrong during communication, the sender must retransmit the affected data to the receiver.

But since retransmission means redoing work that’s already been done, various methods are used to minimize this retransmission overhead.

How Do We Know an Error Occurred?

There are broadly two ways for TCP endpoints to detect errors.

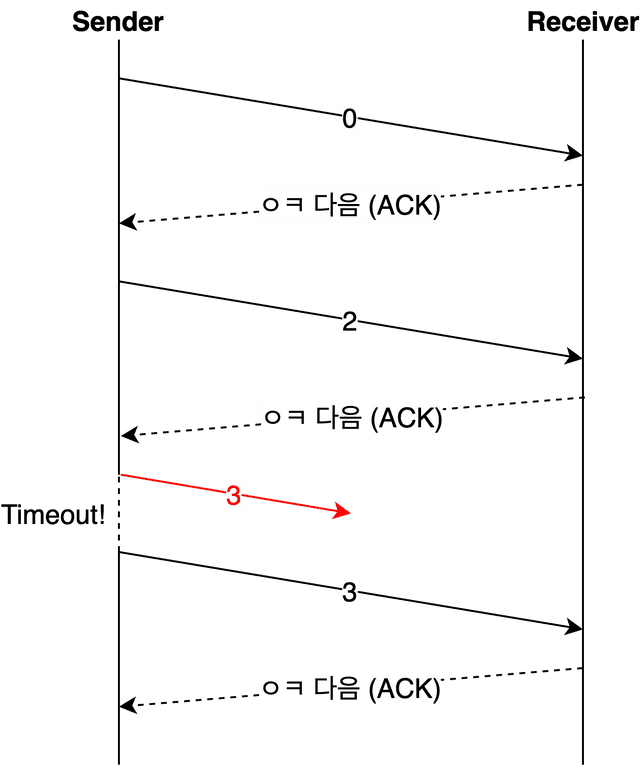

The first is the receiver explicitly sending a NACK (negative acknowledgment) to the sender. The second is inferring an error when the sender doesn’t receive an ACK (positive acknowledgment), or keeps receiving duplicate ACKs.

At first glance, NACK might seem more straightforward, but using NACK requires additional logic on the receiver’s side to decide whether to send an ACK or NACK. So in practice, inferring errors using only ACKs is the more common approach.

A timeout occurs when data sent by the sender is lost in transit (so the receiver never received it and therefore never sent an ACK), or when the receiver responded correctly but the ACK packet itself was lost.

In both cases, from the sender’s perspective, it sent data and the receiver didn’t respond within a certain time period.

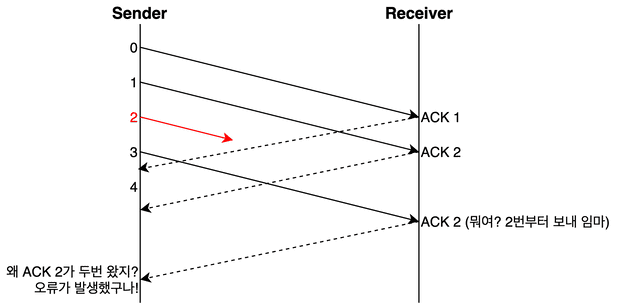

The second method — detecting errors through duplicate ACKs — works roughly like this:

To put this more simply: the sender has already sent SEQ 2, but the receiver keeps saying “hey, it’s time to send me number 2.” The sender can then infer that something went wrong with its data number 2.

However, since TCP uses packet-based transmission where arrival order isn’t guaranteed, receiving one or two duplicate ACKs doesn’t immediately trigger an error determination. Typically, it takes three duplicate ACKs before an error is declared.

Stop and Wait

Stop and Wait is the same approach we looked at in flow control — send data, wait for a positive response, then send the next piece.

It appears again in error control because it inherently provides basic error control. Two birds with one stone, if you will. Since data keeps being retransmitted until a positive response arrives, it handles both flow control and error control.

However, when using sliding window for flow control, data within the window needs to be sent continuously. Using Stop and Wait for error control would negate the benefits of sliding window.

For this reason, more efficient and smarter ARQ methods are generally used instead.

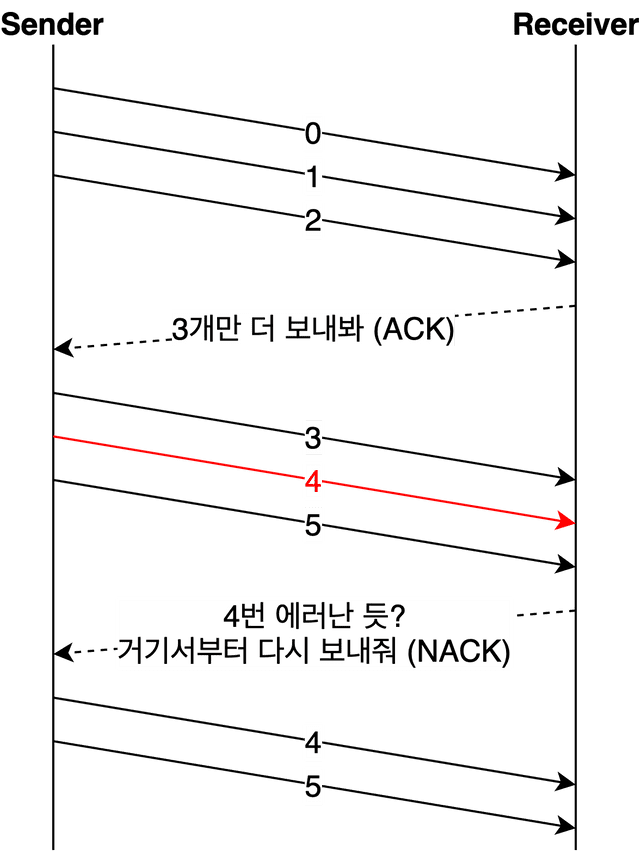

Go Back N

Go Back N sends data continuously and then checks which piece of data first caused an error.

As mentioned above, detecting errors through ACK anomalies is more commonly used in practice, but assuming the receiver uses NACK makes the diagrams easier to follow. So for explaining error control techniques, I’ll assume the receiver uses NACK.

Since this section focuses on explaining error control techniques, let’s concentrate on how errors are controlled rather than how they’re detected.

With Go Back N, after sending data continuously, a single ACK or NACK is enough to understand the receiver’s processing status, which makes it a great fit with sliding window flow control.

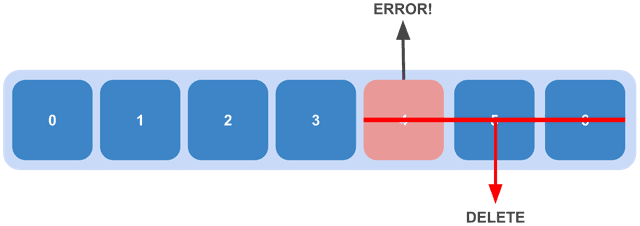

In the diagram above, the receiver detects an error starting from data number 4 and tells the sender “resend everything from number 4.”

In Go Back N, when the receiver detects an error in data number 4, it discards all data it received after number 4 and sends a NACK to the sender.

A ruthlessly cool approach — when an error occurs, perfectly good data after it gets tossed too

A ruthlessly cool approach — when an error occurs, perfectly good data after it gets tossed too

This means the sender, upon receiving the NACK, must retransmit the errored data number 4 and everything it sent after it. Even though the sender had transmitted up to number 5, it has to go back to number 4 and retransmit from there — hence the name Go Back N.

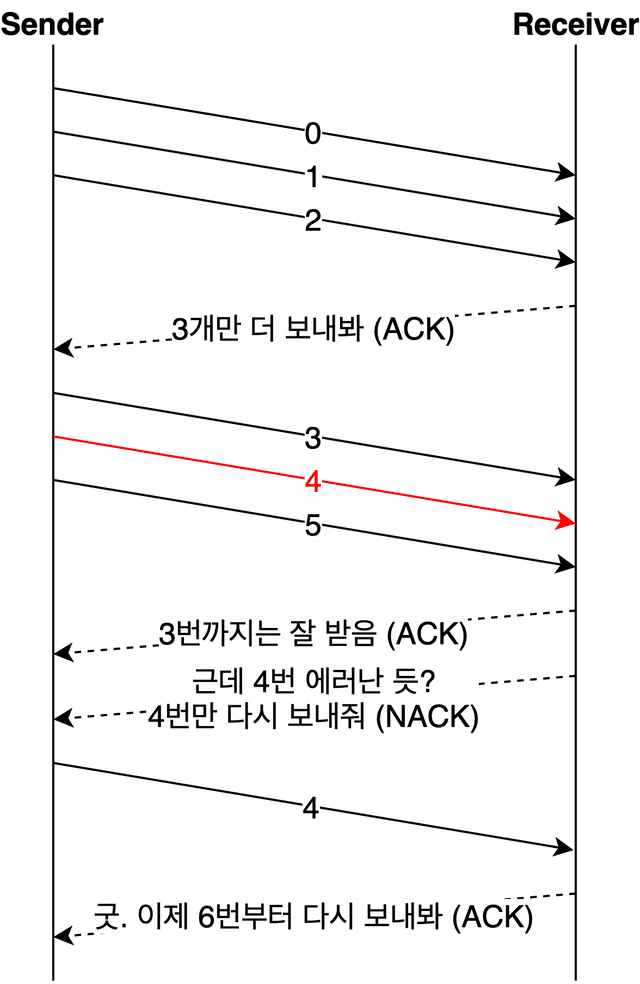

Selective Repeat

Selective Repeat means exactly what it sounds like — selective retransmission. While Go Back N is much more efficient than Stop and Wait, it still has the inefficiency of discarding and retransmitting data that was successfully delivered after the error point.

So the approach of “just retransmit the errored data” was born.

At first glance this seems nothing but efficient and wonderful, but unlike Stop and Wait and Go Back N, there’s a drawback: the data in the receiver’s buffer is no longer sequential.

Looking at the example above, the receiver’s buffer wouldn’t contain 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 in order — it would have 0, 1, 2, 3, 5 with the discarded 4 missing. When the sender retransmits 4, the receiver needs to insert it somewhere in the middle of the buffer and sort the data.

Since you can’t sort data in place within the same buffer, a separate buffer is needed.

In the end, the retransmission step was eliminated but a reordering step was added. When retransmission is more advantageous, use Go Back N; when reordering is more advantageous, use Selective Repeat.

If you want to use Selective Repeat in TCP communication, set the SACK option to 1 — though in practice it’s usually enabled by default.

$ sysctl net.inet.tcp | grep sack:

net.inet.tcp.sack: 1On macOS, using the sysctl command to check TCP-related kernel variables shows net.inet.tcp.sack set to 1.

Given that in most cases it’s more beneficial for the receiver to handle reordering than to traverse the jungle of the network again, it makes sense that Selective Repeat is the default.

Wrapping Up

The hardest part about studying TCP recently has been how many different concepts are intertwined within this single topic.

Being a nearly 50-year-old protocol, TCP has accumulated a massive number of improvements and options compared to its early versions. So whenever you try to dig into any single TCP behavior, everything else comes along for the ride like a chain of sausages.

For example, the window size discussed in the sliding window section isn’t simply set to whatever the receiver reported. It’s determined by comprehensively considering various network-related variables like RTT, MTU, and MSS. To be precise, the sender’s final window size is the smaller of two values: the window size reported by the receiver and the window size the sender determined based on network congestion.

Additionally, the error detection techniques discussed in the error control section are also an important part of congestion control. They feed into the logic that resets the sender’s window size, followed by retransmission using whichever error control technique both sides agreed upon.

In other words, even though this post didn’t cover it, congestion control content is mixed into the topic of flow control.

Personally, I feel like splitting things into topics like flow, congestion, and error sometimes makes it more confusing. I considered writing a post that ignored these distinctions, but since everyone is used to this categorization, I decided to go along with it.

I actually intended to include congestion control in this post, but when the line count exceeded 500, I decided to split it out. Long posts are exhausting for readers.

In the next post, I’ll cover TCP’s congestion control.

That concludes this post on TCP’s flow control and error control.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Sharing the Network Nicely: TCP's Congestion Control

Programming/NetworkHow TCP Creates and Terminates Connections: The Handshake

Programming/NetworkWhat Information Is Stored in TCP's Header?

Programming/NetworkWhy Did HTTP/3 Choose UDP?

Programming/NetworkThe Path from My Home to Google

Programming/Network