How TCP Creates and Terminates Connections: The Handshake

How does TCP guarantee reliable connections?

Following up on my previous post, What Information Is Stored in TCP’s Header?, this time I want to explore TCP’s handshake process and the TCP states that change throughout it.

Because TCP pursues reliable connections, it goes through a special process called a handshake even when creating and terminating connections — all in the name of ensuring reliability. The endpoints communicating via TCP use this handshake to exchange information needed for communication, such as which TCP options to use and synchronization of packet sequence numbers.

But explaining with words alone isn’t much fun, so I wrote a simple client and server in C, and I’ll include snippets of the packets they exchange during the handshake — captured by secretly eavesdropping on them.

What “Connection-Oriented” Really Means

Before discussing handshakes, I want to talk about the concept of a “connection” that TCP creates and terminates. If you’ve studied TCP, you’ve probably heard of one of its key characteristics: being connection-oriented.

Connection-oriented literally means it aims to maintain a connected state. “Connected” and “connectionless” are terms you encounter repeatedly when studying networking. Personally, I found these terms a bit confusing at first.

Common sense tells you that two devices need some kind of connection — whether a cable or otherwise — to communicate. So I didn’t understand why they bothered distinguishing between connection-oriented and connectionless.

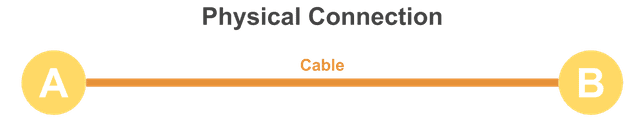

The confusion arises from the difference between physical connections and logical connections.

When we normally think of connecting one device to another, we picture scenarios like connecting a computer to a monitor or plugging a USB into a computer. That is, physical connections between devices.

Using a cable to physically connect two devices

Using a cable to physically connect two devices

In contrast, the “connection” in “connection-oriented” refers to a logical connection. Of course, devices still need physical connections to communicate with each other.

To put it more simply, it means two devices maintain an ongoing state of being connected to each other.

Using a phone as an example: the phone being connected to the phone line is a physical connection, while actually being on a call with another phone is a logical connection — a connected state.

So why does TCP maintain this connected state? The reason is simple: to ensure the reliability of continuous data transmission.

TCP uses packet switching, so it splits data into multiple packets before sending them. Rather than blasting all the data through the network at once, it bundles them into units and streams them to the other party.

Now think from the receiver’s perspective. One advantage of packet switching is that it doesn’t monopolize the circuit — multiple simultaneous communications can happen over limited bandwidth.

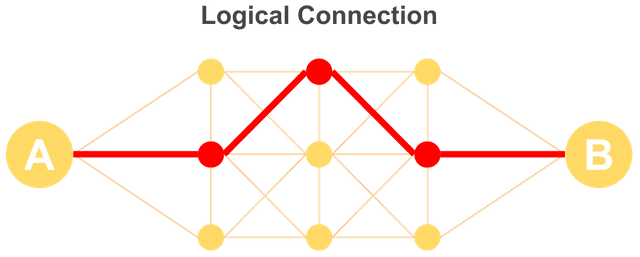

This means each endpoint is simultaneously exchanging packets with multiple devices. Without information like “who sent this” and “which packet number is this,” the receiver would be extremely confused.

Trying to distinguish connectionless packets is like trying to tell apart water mixed in a single bucket

Trying to distinguish connectionless packets is like trying to tell apart water mixed in a single bucket

In the diagram above, think of the pipes as physical connections, the openings at the end of each pipe as ports, and the bucket as the process that handles packets. Trying to distinguish packets without connection state is like trying to identify which pipe opening a particular bit of water in the bucket came from.

That’s why TCP maintains separate connection states — A’s connection with B, A’s connection with C, and so on. To create or release these connection states, TCP goes through a special process called a handshake.

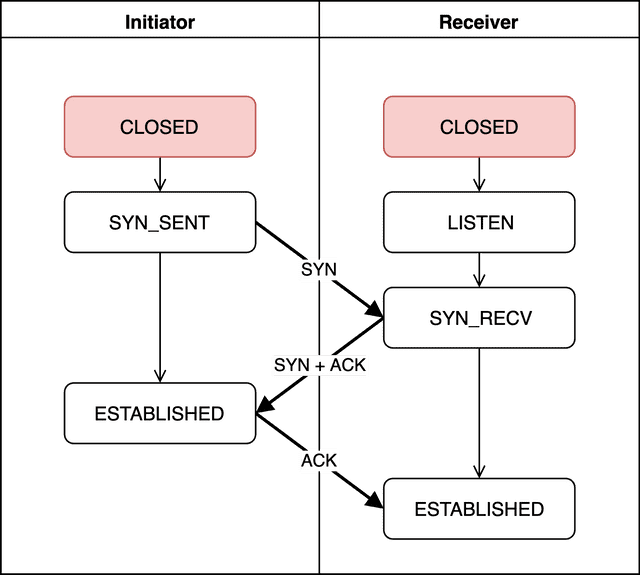

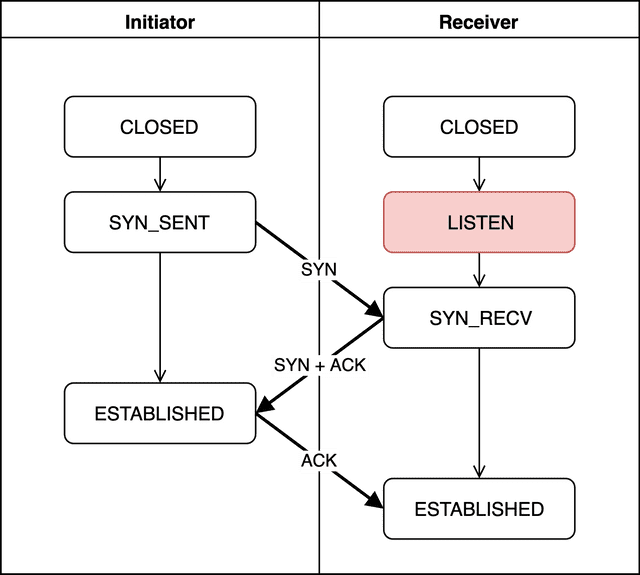

3-Way Handshake

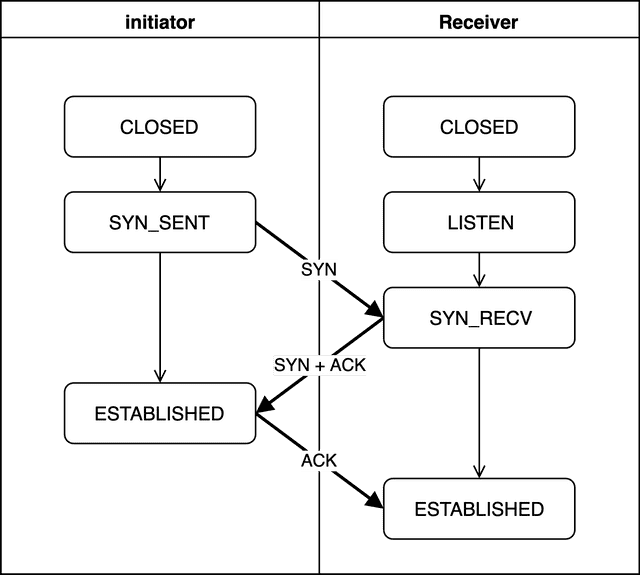

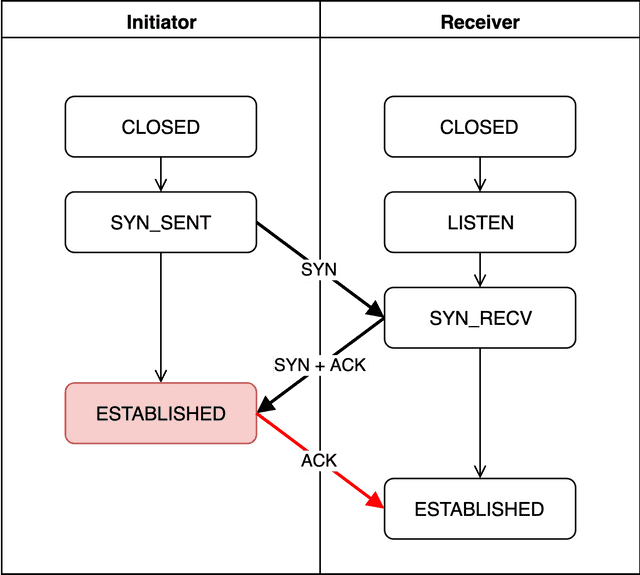

Let’s start by looking at how connections are created. The handshake for creating a connection is called the 3-Way Handshake — as the name suggests, it involves exactly 3 rounds of communication.

Through this process, both endpoints exchange information like who they’re communicating with and what sequence number to expect for incoming data, establishing the connection state.

Here, the initiator is the side that sends the connection request first, and the receiver is the side that receives it. I use these terms because either the client or the server can freely initiate the connection request.

Let’s examine what each state means and what the SYN and ACK being exchanged represent.

CLOSED

No connection request has been initiated yet, so there’s no connection at all.

LISTEN

The receiver is waiting for a connection request from the initiator.

The receiver stays in this state until the initiator sends a request. Since it doesn’t actively reach out, this state is called Passive Open, and the receiver is also known as the Passive Opener.

In socket programming, after socket binding, calling the listen function puts the receiver into the LISTEN state.

if ((listen(sockfd, 5)) != 0) {

printf("Listen failed...\n");

exit(0);

}

else {

printf("Server listening..\n");

}Once the receiver detects a connection request from the initiator, it calls the accept function to proceed to the next step.

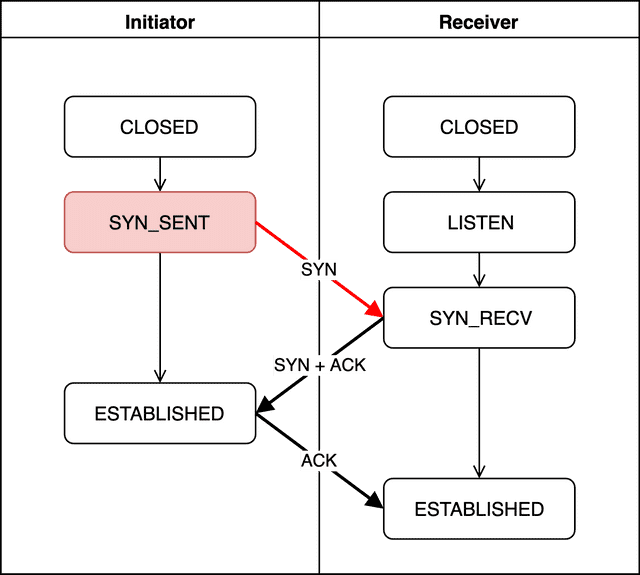

SYN_SENT

The initiator sends a connection request to the receiver, generating a random sequence number and including it in the SYN packet. From this point on, both sides will use this sequence number to create new values, verifying the connection state and packet order through mutual confirmation.

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [S], seq 3414207244, win 65535Capturing this with tcpdump — a utility that can capture TCP segments — we can see the initiator setting the packet flag to S (meaning SYN) and sending the sequence number 3414207244 to the receiver.

Since the initiator is actively reaching out to create a connection, this state is called Active Open, and the initiator is also known as the Active Opener.

SYN_RECV

SYN_RECV means the receiver has properly received the initiator’s SYN packet.

The receiver then creates an acknowledgment number — confirming it received a valid sequence number — and sends it back to the initiator. This acknowledgment number is initiator's sequence number + 1.

Creating this acknowledgment number isn’t complicated. As I discussed in the previous post, when actually exchanging data over TCP, the acknowledgment number is calculated as peer's sequence number + bytes of data sent by peer. It’s essentially a marker saying “I’ve received up to here, so send from here next time.”

But during the handshake, no actual data is being exchanged yet, so there’s nothing to add to the sequence number. However, using the same sequence number back and forth would make it impossible to distinguish packet order. So they simply add 1.

We can verify this with tcpdump as well:

localhost.receiver > localhost.initiator: Flags [S.], seq 435597555, ack 3414207245, win 65535The receiver’s packet has the flag set to S.. The . means the ACK flag field in the header is set to 1, indicating this packet contains a valid acknowledgment number.

The receiver is sending the acknowledgment number 3414207245 — which is the initiator’s sequence number 3414207244 plus 1.

We can also see the receiver generating its own random sequence number, 435597555, and sending it along to the initiator.

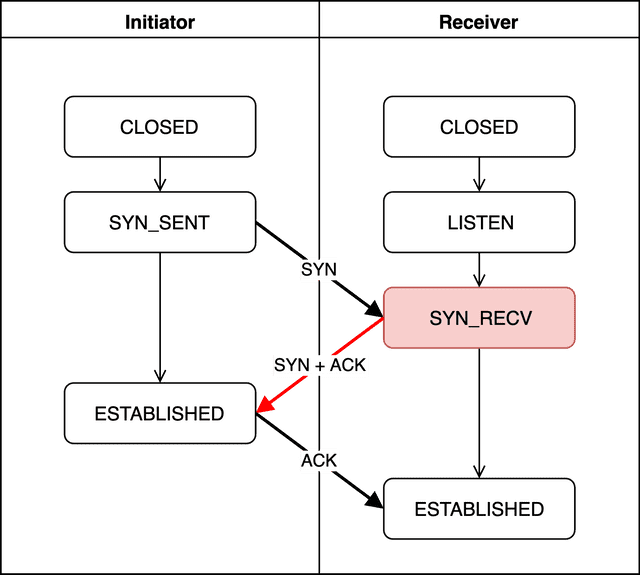

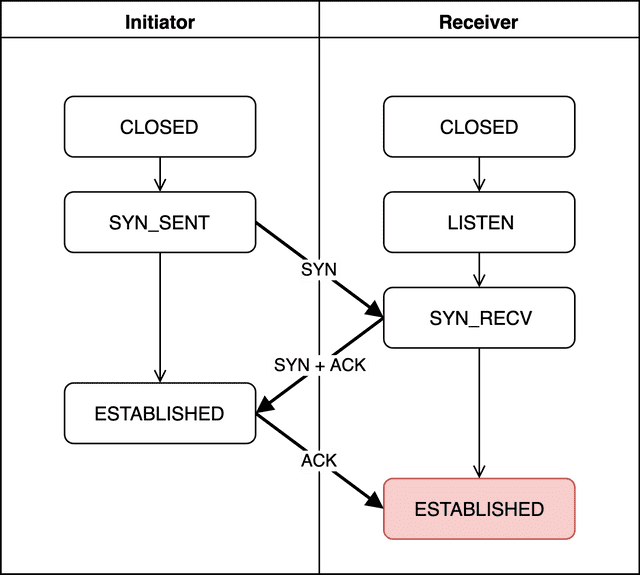

ESTABLISHED (Initiator)

The initiator can verify the connection was properly established by comparing its original sequence number with the acknowledgment number from the receiver (my sequence number + 1). If the difference between its sent sequence number and the received acknowledgment number is 1, it confirms the connection is valid.

The initiator then enters the ESTABLISHED state. It takes the receiver’s newly generated sequence number, adds 1, uses that as its acknowledgment number, and sends it back to the receiver.

So the initiator’s acknowledgment number should be 435597555 + 1 = 435597556… but tcpdump showed something different from what I expected.

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [.], ack 1, win 6379 Why is it showing 1...?

Why is it showing 1...?

The initiator’s final acknowledgment number, which should have been 435597556, somehow became 1. (Confused…)

This is actually not TCP’s own behavior but a tcpdump feature. tcpdump shows sequence numbers as “relative positions” to make them easier to read. Capturing data exchanged between the two endpoints afterward makes this clearer:

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [P.], seq 1:81, ack 1, win 6379, length 80: HTTPThe real acknowledgment number would be 435597556, so the first data packet’s sequence range should be 435597556:435597637.

But since it’s hard for humans to keep analyzing such large numbers, tcpdump shows the acknowledgment as 1 and starts subsequent sequence numbers from 1 for readability. 1:81 is certainly easier to read than 435597556:435597637.

But this is just tcpdump being helpful — the actual values haven’t changed. Using tcpdump’s -S option disables this feature and shows the original numbers:

$ sudo tcpdump -S

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [.], ack 435597556, win 6379ESTABLISHED (Receiver)

Just like the initiator, the receiver checks that the difference between its sent sequence number and the received acknowledgment number is 1. If so, it considers the connection properly established and enters the ESTABLISHED state. At this point, both sides consider the connection safe and reliable, and full communication can begin.

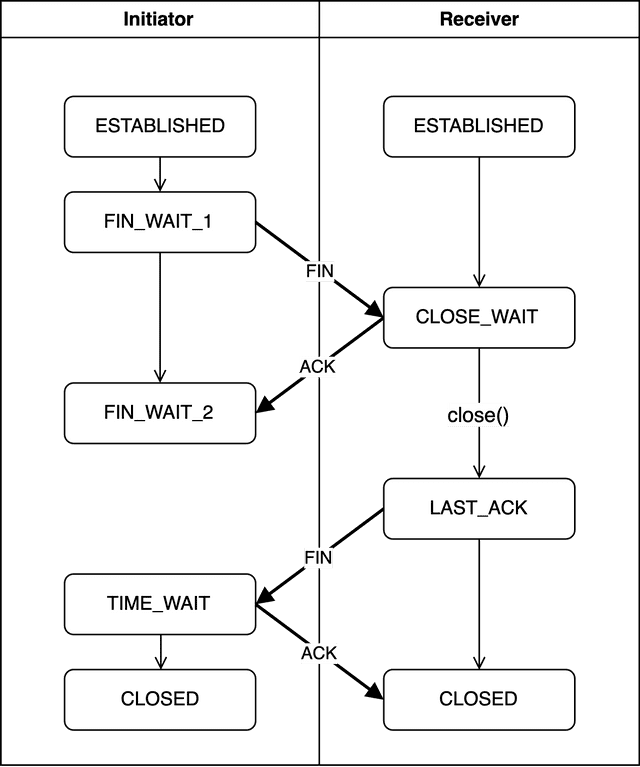

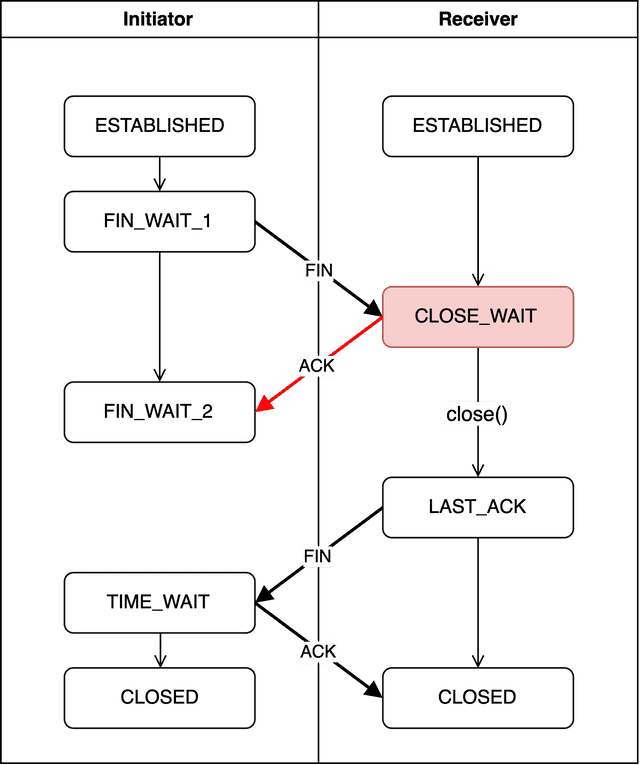

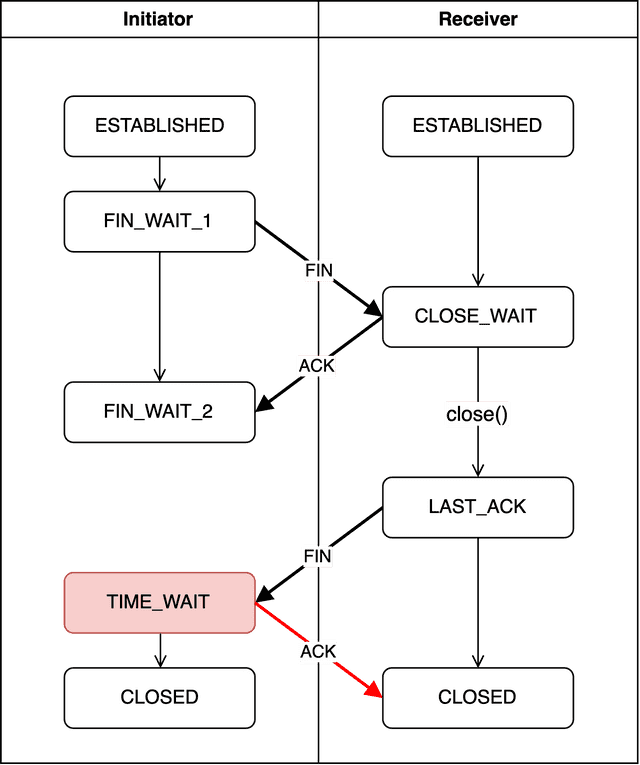

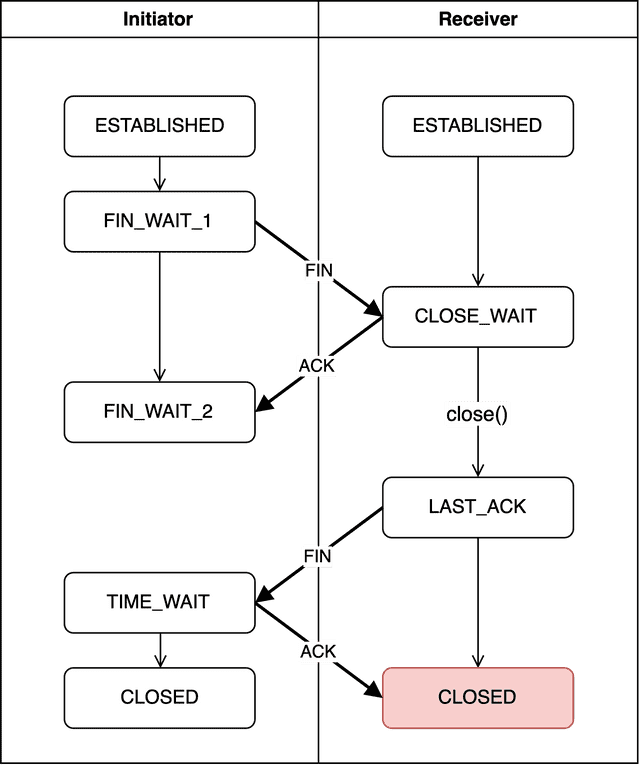

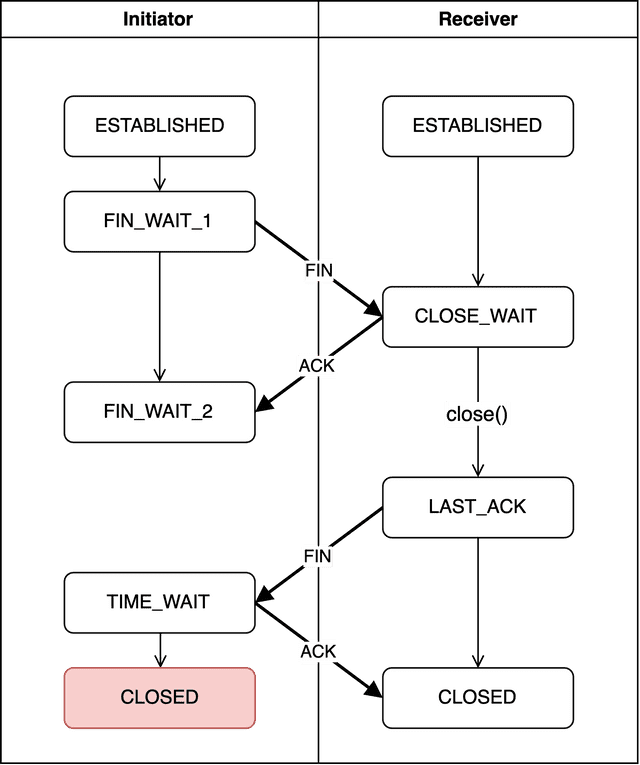

4-Way Handshake

Just as creating a connection requires a special process, terminating one does too.

You might ask “can’t we just cut the connection?” — but if one side unilaterally disconnects, the other side has no way of knowing whether the connection was terminated or is still alive.

There might also be unprocessed data before the connection is terminated, so a process is needed to confirm both sides are ready to properly close the connection.

This process involves 4 rounds of communication, which is why it’s called the 4-Way Handshake.

Again I’m using the terms initiator and receiver — just like with the 3-Way Handshake, either the client or server can initiate the disconnection.

The side that originally requested the connection might initiate the termination, or the side that originally received the connection request might be the one to initiate termination this time.

Developers tend to be more sensitive about the 4-Way Handshake than the 3-Way Handshake. If something goes wrong during connection creation, you can just retry. But if something goes wrong during the 4-Way Handshake — which terminates an already-established connection — the connection remains stuck.

Moreover, unlike the sequential back-and-forth of the 3-Way Handshake, the 4-Way Handshake includes waiting periods where one side waits for the other to respond. If anything goes wrong in between, both sides can end up just waiting for each other — a deadlock.

Of course, depending on configuration, a timeout might kick in after a certain period, forcing the connection closed or advancing to the next step. But during that time, the process is still occupying memory and a port, so for high-traffic servers, this can always cause bottlenecks.

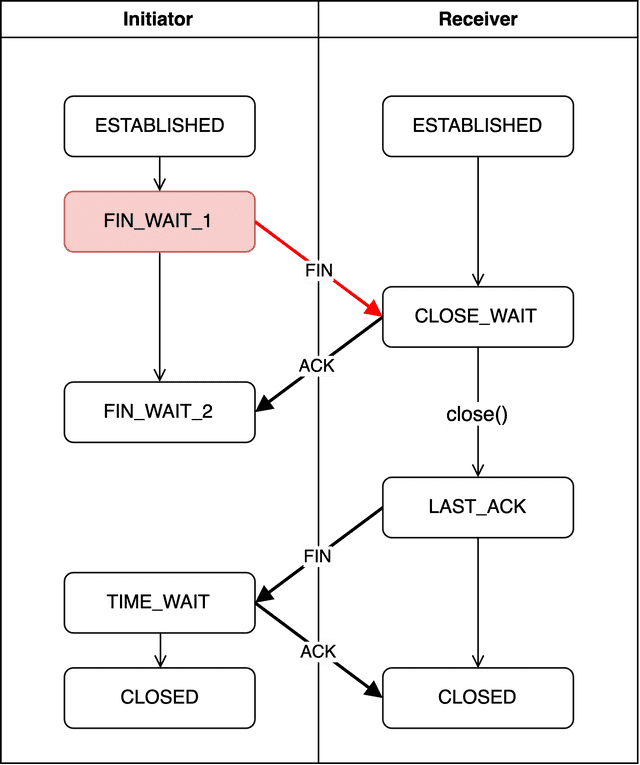

FIN_WAIT_1

The initiator — the side wanting to terminate the connection — sends a FIN packet to the other side and enters the FIN_WAIT1 state.

The FIN packet does include a sequence number, but this time it’s not randomly generated. The 3-Way Handshake needed random initialization because there was no existing sequence number. This time, since sequence numbers already exist, the initiator simply uses whatever sequence number is next in order.

- Initiator ---SEQ: 1---> Receiver

- Initiator <---ACK: 2--- Receiver

- Initiator ---FIN: 2---> Receiver

Think of it as just changing the FIN flag to 1 and sending. The meaning of this flag is basically: “I have nothing more to say.”

Since the initiator is actively initiating the disconnection, it’s called the Active Closer, and this state is called Active Close.

localhost.initiator > localhost.receiver: Flags [F.], seq 701384376, ack 4101704148, win 6378But when I captured the initiator’s termination request, the flag wasn’t F but F. — meaning FIN+ACK. Looking at other blogs that captured packets with tcpdump, I could see most people encountered the same situation.

Theoretically it should be a FIN packet, so why is it being sent as FIN+ACK with an acknowledgment number bundled in?

The Half-Close Technique

The reason the initiator sends a FIN+ACK packet is the Half-Close technique. As the name suggests, instead of fully closing the connection when terminating, you only close half of it.

When using Half-Close, the initiator includes an acknowledgment number in its initial FIN packet. The meaning is: “I’m going to close the connection, but I’ll keep my ears open. I’ve processed up to this acknowledgment number, so if you still have data to send, go ahead.”

In other words, “closing half” means closing only one of the two streams — the send stream — while keeping the receive stream alive.

The receiver can then send any remaining data, and the initiator can process it using its still-alive receive stream and respond with ACK packets. Once the receiver finishes sending all data, it sends a FIN packet back to the initiator, signaling that all data has been processed.

Then the initiator closes the remaining half, terminating the connection more safely.

In socket programming, you can use close() or shutdown() to terminate a connection. Using shutdown() enables Half-Close.

shutdown(sockfd, SHUT_WR);If the initiator uses close(), all streams are destroyed immediately as the socket’s resources are returned to the OS. So even if the receiver belatedly sends unsent data after receiving the FIN packet, there’s no way to process it.

In the example above, passing SHUT_WR as the second argument declares that only the send stream will be closed first.

For more details, search for “Half-Close” or “graceful shutdown” — there’s plenty of material available.

CLOSE_WAIT

After receiving the FIN packet from the initiator, the receiver creates an acknowledgment number using initiator's sequence number + 1 and responds to the initiator, entering the CLOSE_WAIT state.

localhost.receiver > localhost.initiator: Flags [.], ack 701384377, win 6378Since the initiator sent 701384376 as the FIN packet’s sequence number, the receiver’s acknowledgment number becomes 701384377.

The receiver will then continue sending any remaining data, and once everything is sent, it explicitly calls close() or shutdown() to proceed to the next step.

This means the initiator doesn’t know when the receiver will finish processing data, so it must wait until the receiver completes its work and sends back a FIN packet signaling agreement to close.

If the receiver finishes processing data but the termination function isn’t explicitly called at this stage, the connection can’t advance to the next state — creating the potential for deadlock.

Google's autocomplete suggestions speak to the pain of developers caught in deadlocks

Google's autocomplete suggestions speak to the pain of developers caught in deadlocks

Since the receiver only passively prepares to close after receiving a termination request, it’s called the Passive Closer, and this state is called Passive Close.

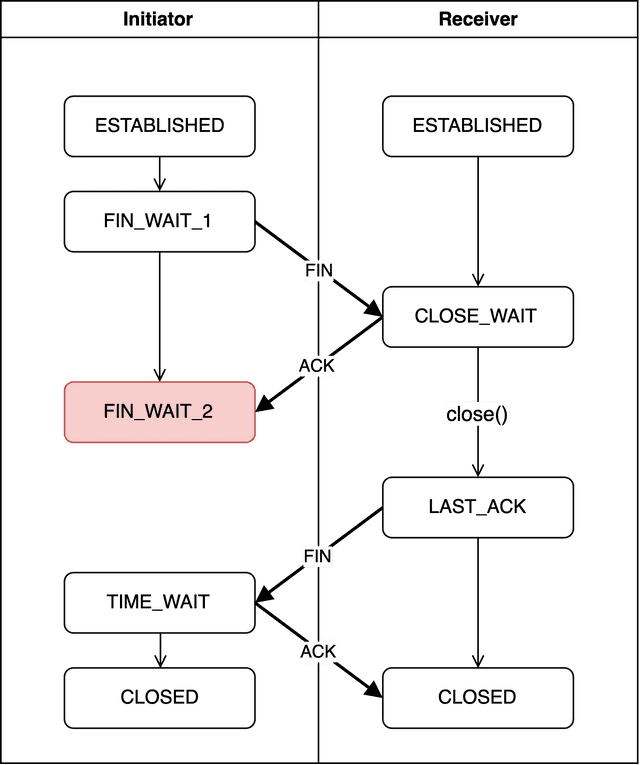

FIN_WAIT_2

The initiator receives the acknowledgment number from the receiver and verifies that the difference between its sent sequence number and the acknowledgment is 1. But since the receiver might not have finished sending all its data, the initiator enters FIN_WAIT2 and waits for the receiver to send a FIN packet granting permission to close.

As I explained in the CLOSE_WAIT section, from this point on the initiator keeps waiting until the receiver sends a FIN packet.

Unlike CLOSE_WAIT, however, it doesn’t wait indefinitely. If a timeout is configured via kernel parameters, the connection can automatically advance to the next step after a certain period.

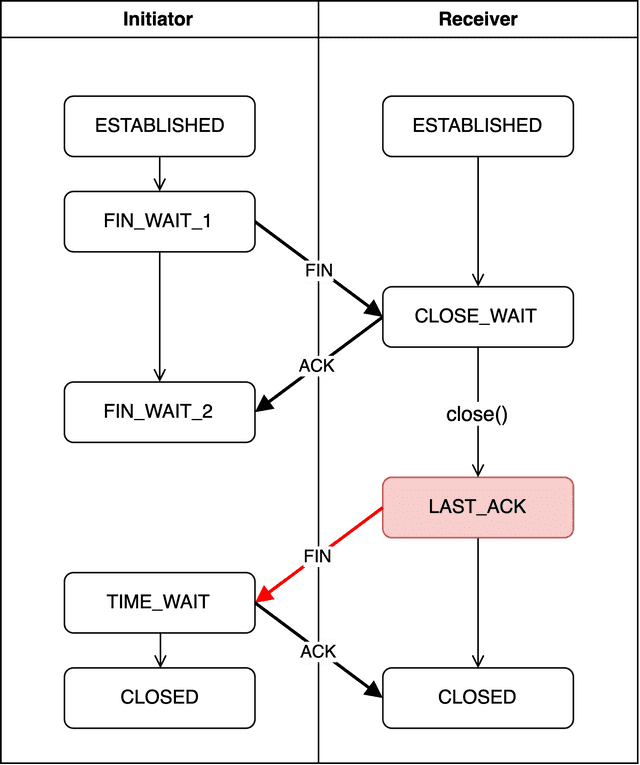

LAST_ACK

Once the receiver has no more data to process, it explicitly calls a termination function and sends another FIN packet to the initiator — signaling agreement to the initiator’s earlier termination request.

The sequence number in this FIN packet uses whatever sequence number the receiver is supposed to send next, and the acknowledgment number reuses the last one it responded with.

The receiver then enters the LAST_ACK state and waits for the initiator to send back an acknowledgment number.

TIME_WAIT

Upon receiving the receiver’s FIN packet, the initiator creates an acknowledgment number using receiver's sequence number + 1 and responds with an ACK packet. The initiator then enters TIME_WAIT, beginning the actual connection termination process. The role of TIME_WAIT is to prevent the connection from falling into deadlock due to unintended errors.

The wait time in TIME_WAIT is defined as 2MSL (Maximum Segment Lifetime), and the exact MSL value is defined by kernel parameters.

$ sysctl net.inet.tcp | grep msl

net.inet.tcp.msl: 15000On my machine (macOS), MSL is set to 15 seconds. So my computer waits about 30 seconds in TIME_WAIT. Note that this value cannot be changed, so the time spent in TIME_WAIT is fixed.

The commonly mentioned TCP timeout parameter net.ipv4.tcp_fin_timeout controls the FIN_WAIT2 timeout and doesn’t apply to TIME_WAIT.

But just like CLOSE_WAIT, deadlocks can occur here too. That’s why many network engineers use various methods — like adjusting the tcp_tw_reuse kernel parameter — to reduce time spent here or eliminate deadlocks caused by bad luck. (A state designed to prevent deadlocks that itself causes deadlocks — the irony.)

But as they say, leaving it alone is usually the best approach.

CLOSED (Receiver)

After receiving the initiator’s ACK packet, the receiver enters the CLOSED state and fully terminates the connection.

CLOSED (Initiator)

After 2MSL has elapsed in TIME_WAIT, the initiator also transitions to CLOSED. As mentioned, this time is fixed by kernel parameters — about 30 seconds on my macOS machine.

Closing Thoughts

And that wraps up my second TCP topic: the handshake. I studied TCP in school, but I’d never examined each state in this much detail, so it was a fresh experience.

Writing this post, I could see just how much work TCP does to ensure reliability even for the simple acts of creating and terminating connections. (Which also made it clear why Google chose UDP for HTTP/3…)

Originally I tried capturing the handshake between my blog’s local server and the browser, but they don’t just exchange a few simple messages — they transfer massive amounts of data, making it difficult to track the specific parts I wanted.

So I ended up doing some socket programming for the first time in a while. Using C after so long was a bit rough on the hands, but it was fun in its own way. C is the kind of thing that’s fun precisely because you only do it occasionally.

If you’d like to try running the example application I used, you can clone it from my GitHub repository. It’s a simple app that just exchanges messages, so it should be easy to peek at packets using tcpdump.

This concludes my post: How TCP Creates and Terminates Connections — The Handshake.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

What Information Is Stored in TCP's Header?

Programming/NetworkSharing the Network Nicely: TCP's Congestion Control

Programming/NetworkTCP's Flow Control and Error Control

Programming/NetworkWhy Did HTTP/3 Choose UDP?

Programming/NetworkThe Path from My Home to Google

Programming/Network