[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes

The real way to implement inheritance in JavaScript — everything about the prototype chain

![[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes [JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes](/static/ffc88c93a54f1c5d1783f61478e57588/01fb2/thumbnail.png)

In this post, continuing from the previous one, I want to talk about various inheritance patterns using prototypes.

JavaScript doesn’t have explicit concepts like inheritance or encapsulation, which is why developers coming from class-based languages like Java or C++ are often confused by the absence of classes in JavaScript.

In other words, inheritance and encapsulation in JavaScript are essentially design patterns — implemented by OOP-minded developers using prototypes to approximate these concepts in JavaScript.

Inheritance in JavaScript is implemented using the prototype chain, and encapsulation is implemented using closures. In this post, I’ll focus on explaining inheritance patterns using prototypes.

Properties and Methods Can Be Shared Through the Original Object

Before diving into object inheritance, let’s look at how to assign properties and methods when creating objects. In the previous post, I explained that JavaScript uses functions, not classes, to create objects.

function User () {}

const evan = new User();The evan object created by calling User as a constructor is a clone of the User.prototype object — the original object.

There are two ways to assign properties or methods to newly created objects. The first is declaring them using this inside the constructor function. The second is declaring them on the prototype object — the original object that new objects are cloned from.

Let’s first look at defining properties and methods using this.

Using this Inside the Constructor Function

In JavaScript, you can assign properties and methods to objects using this inside a constructor function, similar to other languages.

function User (name) {

'use strict';

this.say = function () {

console.log('Hello, World!');

};

}

const evan = new User();

console.log(evan.say());Hello, World!The reason I used strict mode inside the constructor function is to prevent this from being evaluated as the global object if the constructor is accidentally called without the new keyword. (This isn’t directly related to prototypes, so I won’t go into detail.)

This approach is intuitive because it resembles how constructors work in other languages. Since this inside the constructor refers to the newly created object, properties and methods defined through this are freshly created every time an object is instantiated using this constructor.

To see what that means more concretely, let’s create two objects using the constructor and compare their methods.

const evan = new User();

const john = new User();

console.log(evan.say === john.say);falseWhen the constructor was called, this referred to the evan object and the john object respectively, and say was directly assigned to each. Since JavaScript’s strict equality operator (===) considers objects in different memory locations as different, these two methods are completely separate functions stored in different memory.

If you print the evan object, you can see the say method defined directly inside it.

console.log(evan);User {say: function}The reason I’m emphasizing something so obvious is to clearly contrast it with the approach I’m about to describe — defining methods on the prototype object. Using the prototype object produces an entirely different result.

Defining on the Prototype Object

This time, let’s define a method on User.prototype — the prototype object of the User constructor. How does this differ from defining with this?

function User (name) {}

User.prototype.say = function () {

console.log('Hello, World!');

}

const evan = new User();

console.log(evan.say());Hello, World!It seems to work the same as the method defined with this. You might think it’s identical, but there’s an important difference between the two approaches.

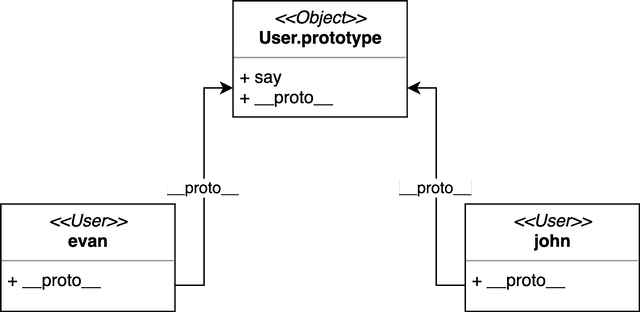

The difference is whether all objects created through the constructor share the method or not. Let’s create two objects again and compare their methods.

const evan = new User();

const john = new User();

console.log(evan.say === john.say);trueThis time, unlike before, the two objects’ methods are the same. That’s because evan.say and john.say aren’t methods defined separately on each object — they’re sharing the method from the original object.

If you print the evan object, you can see what “sharing the original object’s properties and methods” means.

console.log(evan);User {}The evan object is completely empty — no methods or properties at all.

In other words, when you define methods or properties on the original object instead of using this inside the constructor, the created objects don’t have those properties themselves — they reference the original object’s properties and methods.

If you don’t properly understand this distinction, you can end up in situations like this:

User.prototype.name = 'Evan';

console.log(evan.name);

console.log(john.name);Evan

EvanSo if you want each object to have its own unique properties, you should define them using this inside the constructor, not on the original object. To repeat: properties and methods defined on the original object are shared among all created objects.

One curious thing is that the evan object had no properties or methods, yet I was able to access the say method through evan.say. How is that possible?

Prototype Lookup

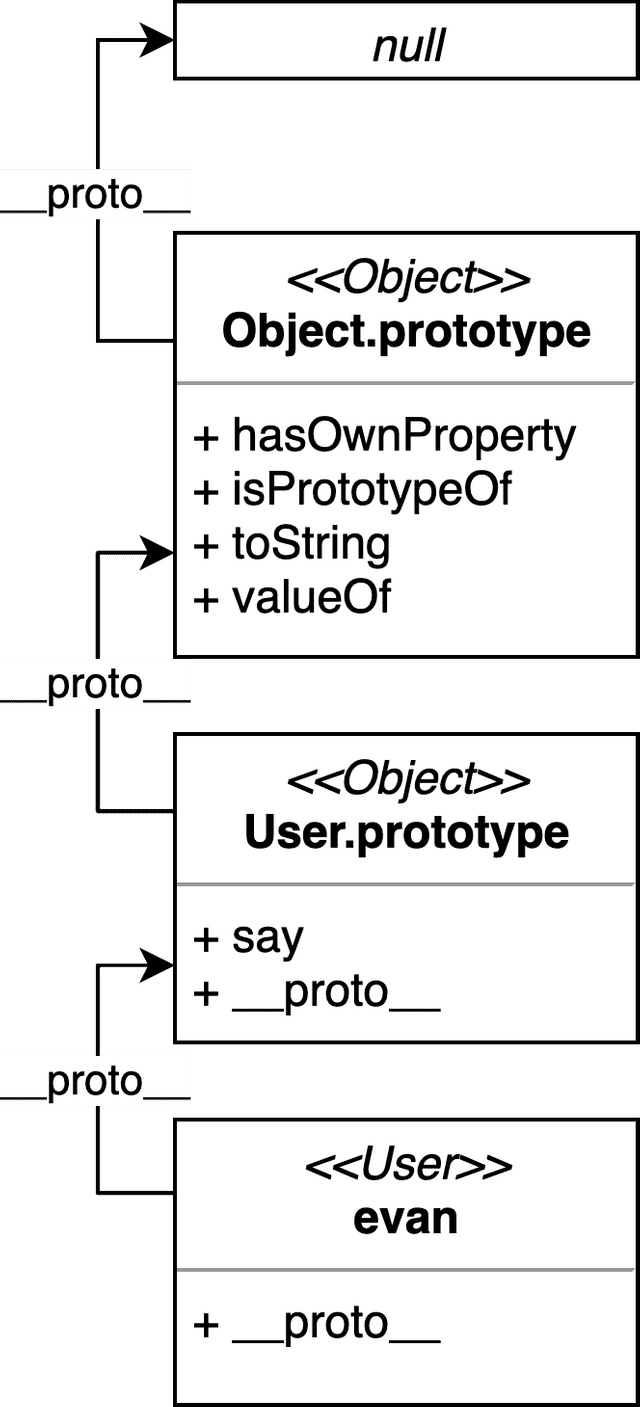

The answer lies in prototype lookup — one of the ways JavaScript searches for properties within an object. Here’s what happened when JavaScript found the say method on the evan object:

- Attempt to access

evan.say- Hmm, no

sayproperty here? Let’s follow__proto__up to the original object!User.prototype, do you have asayproperty?- You do? Profit!

When you try to access a property on an object, JavaScript first checks whether that object has the property. If it doesn’t, it follows the prototype link up to the original object and checks again.

This persistent search continues all the way up to Object.prototype — the ancestor of all objects. If the property doesn’t exist even there, only then does it return undefined.

This means every object can access the properties and methods of all original objects in its prototype chain.

Put simply, the evan object we just created has no properties or methods of its own, but it can use the say method defined on User.prototype (its original) as well as methods like toString or hasOwnProperty from Object.prototype.

Prototype lookup is performed every time you access a property or method, which makes it feel a bit different from inheritance in class-based languages where all inheritance relationships are evaluated when the class is defined.

But abstractly speaking, since it’s inheriting the parent (original) object’s attributes, we can implement inheritance based on prototype lookup.

Inheritance Using Prototypes

There are broadly two ways to implement inheritance using prototypes in JavaScript: using the Object.create method, and without it (the ugly way).

In practice, Object.create alone is more than enough for prototype-based inheritance. The reason I mention both is that Object.create is only supported from Internet Explorer 9 onwards.

But since this post is written for my own happiness, I’d rather not go into detail about IE 8 and below environments. I’ll simply attach a link to my GitHub Gist with the code for the non-Object.create approach.

Use Object.create

The Object.create method takes as its first argument the object that will serve as the new object’s original, and as an optional second argument, properties to add to the new object.

Object.create(proto: Object, properties?: Object);The second argument is optional, and rather than simply passing something like { test: 1 }, you need to specify data descriptors and accessor descriptors, like you would with Object.defineProperties.

Object.create(User.prototype, {

foo: {

configurable: false,

enumerable: true,

value: 'I am Foo!',

}

});For the detailed meaning of each property, check MDN Web Docs: Object.defineProperties.

The key point of this method is that you can specify an object’s prototype object, which means you can manipulate the prototype chain however you want. You can even change it dynamically. (This is honestly one of JS’s more wild aspects…)

Now let’s implement inheritance using Object.create and prototypes.

function SuperClass (name) {

this.name = name;

}

SuperClass.prototype.say = function () {

console.log(`I am ${this.name}`);

}First, I created a SuperClass constructor function to serve as the parent class and defined a say method on its prototype object. Now let’s implement the child class constructor and define the inheritance relationship.

function SubClass (name) {

SuperClass.call(this, name);

}

SubClass.prototype = Object.create(SuperClass.prototype);

SubClass.prototype.constructor = SubClass;

SubClass.prototype.run = function () {

console.log(`${this.name} is running`);

}It might look like a lot, but when you break it down piece by piece, it’s fairly straightforward.

SuperClass.call(this)

The Function.prototype.call method changes the execution context of the called function to whatever is passed as the first argument. In other words, it changes the target of this.

So SuperClass.call(this, name) means: call the parent constructor, but change the execution context to the child constructor. Think of it as the JavaScript equivalent of calling super in Java.

I used call here, but anything that changes the parent constructor’s execution context works fine — apply or bind would do the job equally well.

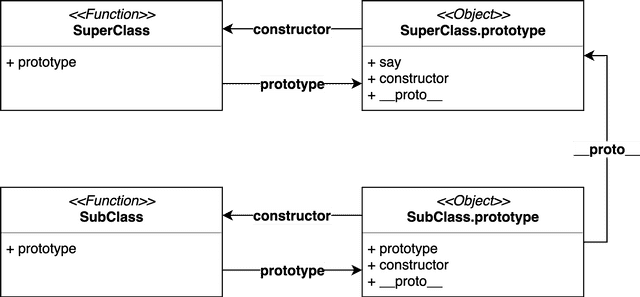

Changing SubClass.prototype

Next, I used Object.create to create a new object with SuperClass.prototype as its original, and assigned it as SubClass’s prototype object. This creates a prototype chain — in other words, a parent-child relationship — between the child constructor’s prototype object and the parent constructor’s prototype object.

Changing SubClass.prototype.constructor

Since we cloned the parent constructor’s prototype object verbatim, the new child constructor’s prototype object still has its constructor property pointing to the parent constructor SuperClass.

But objects created through SubClass shouldn’t appear as if they were created using SuperClass, so we need to reassign the constructor property to SubClass.

After all these steps, the following relationship is established:

Now let’s create an object using the SubClass constructor and verify that it properly inherits the parent constructor’s attributes.

const evan = new SubClass('Evan');

console.log(evan);

console.log(evan.__proto__);

console.log(evan.__proto__.__proto__)SubClass { name: 'Evan' } // The evan object

SubClass { constructor: [Function: SubClass], run: [Function] } // evan's original object

SuperClass { say: [Function] } // The original of evan's original objectThe evan object was properly created by cloning SubClass’s prototype object, and the chain of original objects is correctly linked.

In other words, the prototype chain evan → SubClass.prototype → SuperClass.prototype is complete. When you call run or say on the evan object, prototype lookup kicks in to find and call the method from the original objects.

Wrapping Up

Continuing from the previous post, I’ve covered inheritance patterns using prototypes in JavaScript.

Honestly, I’ve rarely had to implement inheritance using these patterns in production. ES6 came out shortly after I started working as a developer, and since I was more familiar with Java at the time, I was completely absorbed by the new class keyword.

But after a few years on the job, I encountered these inheritance patterns fairly often in legacy code, and they sometimes came up in interviews too, so they’re definitely worth studying.

Even though ES5 is rarely used these days, these inheritance patterns are still foundational to JavaScript program architecture.

That wraps up this post on implementing inheritance with prototypes.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Beyond Classes: A Complete Guide to JavaScript Prototypes

Programming/JavaScriptHow Does the V8 Engine Execute My Code?

Programming/JavaScriptJavaScript's let, const, and the TDZ

Programming/JavaScriptHeaps: Finding Min and Max Values Fast

Programming/Algorithm[Making JavaScript Audio Effectors] Creating Your Own Sound with Audio Effectors

Programming/Audio