Beyond Classes: A Complete Guide to JavaScript Prototypes

The real object creation mechanism hidden behind class syntax

In this post, I want to talk about prototypes — a concept you can’t ignore when discussing JavaScript.

Prototypes are very familiar to those who’ve been using JavaScript since the ES5 days, but for developers who started with ES6, classes are the norm, so prototypes might feel like unfamiliar territory.

When I first started frontend development, JavaScript was in the midst of transitioning from ES5 to ES6. Having primarily used Java before switching to frontend development, the concept that gave me the most trouble was prototypes. (And it still does, to be honest.)

Of course, JavaScript’s stature has risen significantly since then, and interest in the prototype pattern has grown with it. Still, the mainstream approach to object creation — both then and now — remains class-based, as seen in C-family languages and Java.

That’s why prototype-based programming feels relatively unfamiliar to developers coming to JavaScript for the first time. This difficulty in transitioning is precisely why the class keyword was introduced in ES6.

Honestly, I’m still more comfortable with class-based object creation myself, so I need to keep studying prototypes too.

That’s why in this post, I want to focus on what the prototype pattern is and how prototypes are used within JavaScript.

Do I Really Need to Know About Prototypes When ES6 Has Classes?

JavaScript has supported classes using the class keyword since ES6. To be precise, it would be more accurate to say classes are implemented by mimicking them with prototypes under the hood.

Many developers call JavaScript’s classes mere “syntactic sugar,” but personally, I think JavaScript’s classes impose stricter constraints than the ES5 prototype-based approach to object creation. So rather than simple syntactic sugar, I’d say they’re more of a superset.

So if we can just use classes, why bother learning about prototypes?

Because even though ES6 supports classes via the class keyword, that doesn’t mean JavaScript has become a class-based language. At the end of the day, classes in JavaScript are prototypes wearing a class costume.

On top of that, a lot of legacy frontend code was written in ES5, so frontend developers still have to work with ES5 fairly often. And even if you want to migrate ES5 code to ES6 or later, you can’t do that migration if you don’t understand the prototype-based object creation and inheritance in the existing code.

Prototype Is a Design Pattern

When people hear “prototype,” they usually think of JavaScript, but prototypes aren’t exclusive to JavaScript — they’re simply a design pattern. Besides JavaScript, many other languages support prototype-based programming, including ActionScript, Lua, and Perl.

So before diving deep into JavaScript’s prototypes, let’s first look at prototype as a design pattern.

The prototype pattern is one of several patterns for efficiently creating objects, primarily used to avoid the high cost of object creation.

When we say object creation is expensive, we literally mean a lot of work has to be done every time an object is created.

For example, imagine you’re implementing a character for an RPG game. This character can equip various items. Since players would be unhappy starting with nothing, you want characters to spawn with some basic equipment.

// Player.java

class Weapon {}

class Armor {}

class BasicSword extends Weapon {}

class BasicArmor extends Armor {}

class Player {

public Weapon weapon;

public Armor armor;

public Player() {

this.weapon = new BasicSword(); // Beginner's wooden sword

this.armor = new BasicArmor(); // Beginner's armor

}

}Here’s a rough sketch. The Player object has to create both a BasicSword and a BasicArmor object when it’s instantiated.

In this case, the creation cost is higher than just creating a Player object alone. And the more items you add to the initial loadout, the higher the creation cost climbs.

Hmm… but thinking about it, if every new character always starts with the same items, we could just create one expensive Player object and clone it from then on.

// This is too expensive...

Player evan = new Player();

Player john = new Player();

Player wilson = new Player();

// What about this approach instead?

Player player = new Player();

Player evan = player.clone();

Player john = player.clone();

Player wilson = player.clone();This is essentially the prototype pattern. There’s a prototype — an original object — and you clone it to create new objects.

In Java, classes that serve as clone targets typically implement the Cloneable interface. Since the Cloneable interface defines a clone method, any class using it must override and implement clone.

class Player implements Cloneable {

//...

@Override

public Player clone () throws CloneNotSupportedException {

return (Player)super.clone();

}

}Once you implement clone, the Player object becomes cloneable — it now has the ability to serve as the original for other objects.

From now on, whenever you need another Player object, you can simply clone an existing one, avoiding the high creation cost.

Player evan = new Player();

Player evanClone = evan.clone();Also, the Player object is copied to a new memory location, but unless you perform a deep copy, the BasicSword and BasicArmor objects it holds aren’t newly created — they just reference the same memory where the originals are stored.

In other words, used wisely, this can save memory. It’s the same principle as how JavaScript uses call by value for primitives and call by reference for everything else.

As some of you might have guessed, this means if you’re not careful, you can end up in this unfortunate situation:

Player evan = new Player();

try {

Player evanClone = evan.clone();

evanClone.weapon.attackPoint = 40;

System.out.println("Evan's weapon attack -> " + evan.weapon.attackPoint);

System.out.println("Clone's weapon attack -> " + evanClone.weapon.attackPoint);

}

catch (Exception e) {

System.err.println(e);

}Evan's weapon attack -> 40

Clone's weapon attack -> 40 Welcome to debugging hell...

Welcome to debugging hell...

To summarize, the prototype pattern is about creating new objects by cloning an original object.

Of course, JavaScript’s prototype system isn’t just about a few objects having clone relationships — every single object in JavaScript is woven into a web of clone relationships, making it a bit more complex. But the fundamental principle still follows the prototype pattern.

Now let’s look at how JavaScript actually uses the prototype pattern when creating objects.

JavaScript’s Prototype

As I explained earlier, the prototype pattern is used for object creation. Java, the language I used for the examples above, supports class-based programming, so you need a special pattern to use the concept of prototypes.

But JavaScript natively supports prototype-based programming, meaning the prototype pattern is applied every time an object is created, automatically.

For that reason, we need to understand what JavaScript means by “object” and what it means for an object to be “created.”

How JavaScript Creates Objects

In computer science, an object is “a real-world entity modeled in a program” — something with properties (characteristics) and methods (behaviors) that mimics something in the real world.

In class-based languages, you create a class and then use it to create objects. But JavaScript can create objects with simple syntax:

const evan = {

name: 'Evan',

age: 29,

say: function () {

console.log(`Hi, I am ${this.name}!`);

}

};This approach is called “declaring an object with a literal.” Since a literal is essentially a shorthand for fixed values in source code, it feels like we’re creating objects with minimal syntax, but internally a whole mechanism for object creation is at work.

For example, in other languages, when you create an object using literal syntax, classes are used internally. In Python, if you declare a dictionary with a literal and check its type, you’ll see the dict class:

my_dict = {

'name': 'Evan',

'age': 29

}

type(my_dict)<class 'dict'>We didn’t explicitly write dict({ 'name': 'Evan', 'age': 29 }) — we used a literal — but internally, it properly used the dict class to create the object.

Similarly, in Java, if you declare an array using literal syntax and print it, you can see it’s ultimately creating the array object based on a class:

String[] array = {"Evan", "29"};

System.out.println(array);[Ljava.lang.String;@7852e922The point is, just like in other languages, JavaScript objects don’t just magically pop into existence — something is being used to create them.

But JavaScript doesn’t have a concept of classes, so what is it using to create objects?

The answer is functions.

To dig deeper into how JavaScript creates objects, let’s declare the evan object from earlier using a different method:

const evan = new Object({

name: 'Evan',

age: 29,

});This looks suspiciously like creating an object using a class in a class-based language. This approach is called creating an object using a constructor.

In a class-based language, Object would be a class, but in JavaScript, it’s a function.

In other words, constructors in JavaScript belong to functions. Let’s verify this by printing Object in the browser console:

console.log(Object);

console.log(typeof Object);ƒ Object() { [native code] }

"function"Yep, Object is unmistakably a function.

This was one of the hardest things for me to accept when I first started using JavaScript.

Coming from class-based programming, new and constructors were things only classes could have. Having a function pop up out of nowhere was hard to wrap my head around. (My brain gets it, but my heart…)

Anyway, now we know that JavaScript uses functions to create objects. Let’s recap what we’ve learned so far:

- The prototype pattern creates objects by cloning an original object.

- JavaScript uses the prototype pattern when creating objects.

- JavaScript uses functions to create objects.

This means that when JavaScript uses a function to create an object, it references and clones something. It’s time to find out what that “something” is.

So What Exactly Gets Cloned?

The prototype pattern as a design concept isn’t that complicated. It’s just about cloning an original object to create a new one.

JavaScript works the same way — it clones something to create new objects. To figure out what that something is, let’s declare a simple function:

function User () {}

const evan = new User();

console.log(evan);

console.log(typeof evan);User { __proto__: Object }

objectAs I mentioned, JavaScript uses functions to create objects, so you can create objects in a way that feels similar to using classes.

So what was evan cloned from? You might think it was cloned from the User function itself, but it was actually cloned from “the prototype object of the User function.”

Wait, prototype just appeared out of nowhere...?

Wait, prototype just appeared out of nowhere...?

This might seem abrupt, but think about it simply. If the function itself were cloned, wouldn’t the resulting object be of type Function rather than Object?

But evan is of type Object. That means something of object type was cloned — not the function itself — and that original object is the User function’s prototype object.

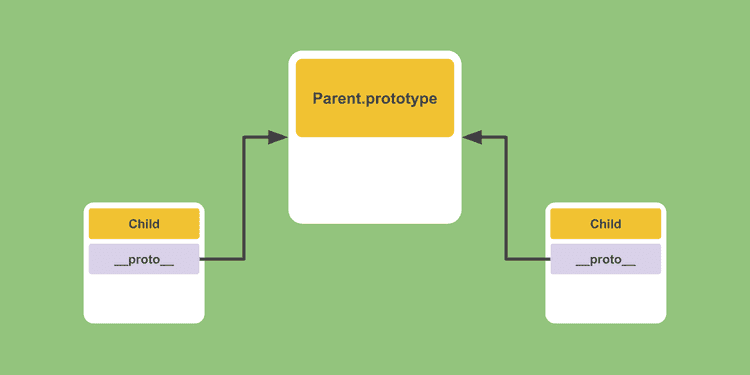

I never explicitly declared a prototype for User, but JavaScript automatically creates a prototype object (Prototype Object) whenever a function is created and links it to the function’s prototype property.

function User () {}

console.log(User.prototype);

console.log(typeof User.prototype);{ constructor: f User(), __proto__: Object }

objectI only declared a function, yet User.prototype has a fully-formed object attached to it like a buy-one-get-one-free deal. The key point is: whenever a function is created, its prototype object is automatically created along with it.

This prototype object serves as the original that gets cloned when you use the function to create new objects.

In other words, when you use new User(), it doesn’t clone the User function itself — it clones the prototype object assigned to User.prototype.

Dear evan object, clone my prototype object, not me

Dear evan object, clone my prototype object, not me

This prototype object, created alongside the User function, is called the prototype property.

So what do the constructor and __proto__ properties inside this prototype object mean?

constructor

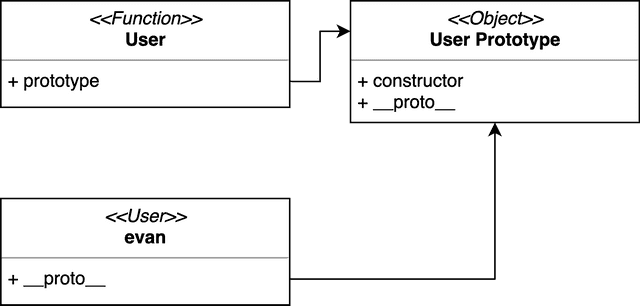

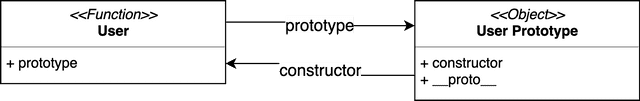

Every prototype object that’s created alongside a function has a constructor property. This property holds a reference to the function that was declared when the prototype object was created.

console.log(User.prototype);{

constructor: f User(),

__proto__: Object

}When you declare a function, both the function and its prototype object are created and linked to each other. The function is linked via the prototype object’s constructor property, and the prototype object is linked via the function’s prototype property.

The function and prototype object are linked to each other

The function and prototype object are linked to each other

console.log(User.prototype.constructor === User);trueFrom the perspective of an object created through this function, the constructor property answers the question: “Which function was called to create me?” Without this link, a newly created object would have no way of knowing which constructor function was used.

A newly created object has a link to which original object it was cloned from, but not to which constructor was called — so it accesses the original object’s constructor property to find out.

const evan = new User();

console.log(evan.__proto__.constructor === User);trueThe property that lets a created object access its original object is the __proto__ property.

__proto__

When I explained the constructor, I mentioned that objects created through a function have a link to their original object. This link is called the prototype link.

Every object in JavaScript — except Object.prototype — was created by cloning an original object, so every object has a prototype link pointing to its original. That link is stored in the __proto__ property.

I’ll explain why Object.prototype.__proto__ doesn’t exist later. For now, just focus on the fact that objects have prototype links to their originals.

This post uses the

__proto__property for clarity. However, while it was standard in ECMAScript 2015, it is no longer standard, so usingObject.getPrototypeOf()is recommended.

Objects created using the User function are cloned from the User.prototype object, so they store User.prototype in their __proto__ property.

function User () {}

const evan = new User();

console.log(evan.__proto__ === User.prototype);trueSo if we keep following the prototype links to trace back to the original objects, shouldn’t we eventually find out which ultimate original object every JavaScript object was cloned from?

Prototype Chain

Every object used in JavaScript is defined and created through this prototype-based approach. That means built-in objects like String, Boolean, and Array were all created the same way.

So what prototype objects were they cloned from?

Whether it’s String, Boolean, Array, or anything else — everything in JavaScript is cloned starting from Object.prototype, the prototype of the Object function.

When I explained __proto__ earlier, I mentioned that Object.prototype has no prototype link — no link to an original object. That’s because Object.prototype is the ancestor of all objects.

To verify this, pick any object and follow its __proto__ chain upward.

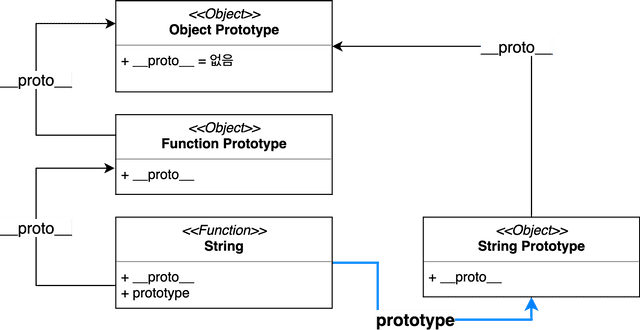

Let’s use String since it’s an easy target. Note that depending on whether you start from the String constructor function or a String object, the path to the ancestor differs — because they obviously have different originals. I chose the String constructor function.

const first = String.__proto__;

const second = first.__proto__;

console.log('First ancestor -> ', first.constructor.name);

console.log('Second ancestor -> ', second.constructor.name);First ancestor -> Function

Second ancestor -> ObjectEvery function in JavaScript has Function.prototype as its original. And since Function.prototype is itself an object, it naturally has Object.prototype as its original.

What happens if we go one more level up?

const third = second.__proto__;

console.log(third.constructor.name);Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'constructor' of null at <anonymous>:1:28A TypeError. The error message tells us that Object.prototype.__proto__ is null.

In other words, there’s nothing above Object. Here’s a simple diagram of this relationship:

It looks complex, but it’s straightforward. The String constructor function’s original object is Function.prototype. A String object declared like const a = 'evan' has String.prototype — the prototype of the String constructor — as its original. And since String.prototype is an object, it naturally has Object.prototype as its original.

This web of prototype relationships is called the prototype chain.

Wrapping Up

The reason I decided to write about prototypes was that I recently got a question in a job interview asking me to implement a Private Static method using JavaScript prototypes — and I couldn’t solve it.

It was a problem that required combining closures and prototypes, but my fundamentals weren’t strong enough to pull it off.

I originally wanted to cover various inheritance techniques using prototypes and member encapsulation with closures as well, but as always, the post got longer than planned, so those topics will have to wait for a separate post.

Honestly, I never think about length control when I start writing

Honestly, I never think about length control when I start writing

For developers like me who are used to class-based object creation, JavaScript’s prototypes feel quite complex. The prototype pattern as a design concept is simply “clone an object to create a new one,” but JavaScript’s prototype chain is far more intricately connected than that.

That said, while prototype chains and various inheritance techniques can feel daunting, the core skeleton of prototypes isn’t that hard:

- Objects are created using functions, and they’re created by cloning the function’s prototype object.

- Every object has information about which original object it was cloned from.

Of course, you can do wild things like dynamically changing the reference to the original object at runtime, and there are various techniques built on top of that. But at the end of the day, it comes down to those two principles. In the next post, I’ll cover inheritance techniques using prototypes and prototype lookup — the mechanism for searching an object’s properties.

That wraps up this overview of JavaScript prototypes.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

[JS Prototypes] Implementing Inheritance with Prototypes

Programming/JavaScriptHow Does the V8 Engine Execute My Code?

Programming/JavaScriptJavaScript's let, const, and the TDZ

Programming/JavaScriptHeaps: Finding Min and Max Values Fast

Programming/Algorithm[Making JavaScript Audio Effectors] Creating Your Own Sound with Audio Effectors

Programming/Audio