Let's Keep Our Commit History Clean

Merge vs. Squash vs. Rebase — when and how to use each

In this post, I want to discuss the differences between three common Git merge strategies: Merge, Squash and merge, and Rebase and merge. I briefly touched on these in a previous post about Git basics, but this time I’ll go into more detail.

All three strategies share the same goal of merging branches, but the way commit history gets recorded differs depending on which one you choose.

These three strategies are supported by both GitHub and Atlassian’s Bitbucket — which speaks to how important it is to be able to choose how your commit history is preserved when merging.

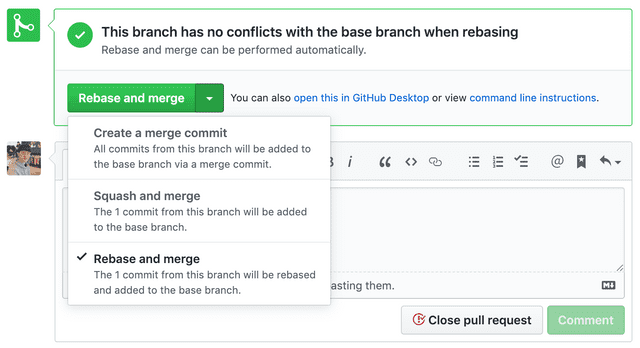

GitHub lets you choose a merge strategy when merging a Pull Request.

GitHub lets you choose a merge strategy when merging a Pull Request.

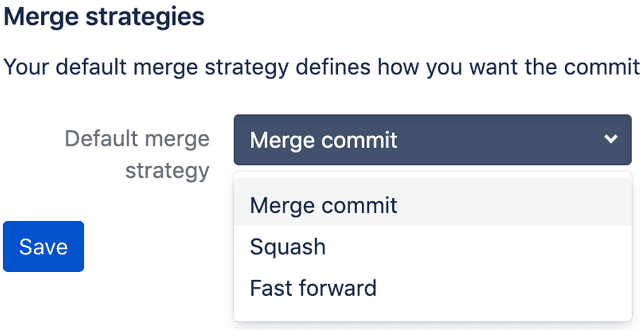

Bitbucket lets you set a default merge strategy in repository settings.

Bitbucket lets you set a default merge strategy in repository settings.

The merge strategy names differ slightly between GitHub and Bitbucket, but they mean the same thing. GitHub’s Create a merge commit corresponds to Bitbucket’s Merge commit, Squash and merge maps to Squash, and Rebase and merge maps to Fast forward.

Each strategy has its own pros and cons, so using them appropriately is key. For example, when using Git Flow, you might use Squash and merge when merging a feature branch into develop, and Merge when merging develop into master — flexibly combining strategies.

But to use them appropriately, you need to understand how each one actually merges branches. So let’s take a closer look at what makes these three strategies different.

Why Does Commit History Matter?

Before diving into merge strategies, let me briefly explain why Git commit history is important. The three strategies I mentioned are essentially about choosing how to record commit history when merging, so it helps to understand why developers care so much about it.

As we all know, a commit is one of Git’s fundamental building blocks. In principle, a single commit represents “one meaningful change.”

This means you should be able to look at a commit message and quickly understand what changed and why. The reason so many developers emphasize meaningful commit messages is that they want to know when and how code was modified just by reading a short message.

A collection of these commits arranged chronologically is called commit history. As the word “history” suggests, it’s literally the story of your program. There are many reasons developers say it’s important to record meaningful history, but here are two major ones.

Easier to Track Down When a Bug Was Introduced

When using Git for version control, we sometimes work alone, but usually we collaborate with multiple developers. The more changes there are — or the larger the program — the higher the chance someone introduces a bug through a minor mistake.

If developers can look at the commit history and quickly understand what code was changed and why, finding the cause of a bug becomes much faster.

For example, imagine a payment-related bug surfaces after a new version release. Developers will naturally start examining payment-related code. But most programs have complex internal dependency chains between modules, making it far from easy to trace everything and find the root cause in a short time. With a well-maintained commit history, you can find the commit that modified payment-related code in this version and quickly see what changed.

If the previous version had no issues and the problem appeared in the current release, the bug is likely caused by code changed in that commit — enabling a faster response.

When You Need to Modify Legacy Code

The second reason is a somewhat sadder scenario: when you need to fix legacy code but the person who wrote it is gone. The reason they’re gone could be… they left the company, or they left the company, or maybe they left the company.

What makes legacy code scary isn’t that the code itself is too complex to understand — it’s that there’s no guarantee modifying it won’t break something else. And since legacy code exists at every company, having to modify it is hardly a rare situation.

If the code has clear separation of concerns or is simple enough, you might modify it without too much worry. But the code we hesitate to touch is usually not just legacy — it’s legacy that’s been aging for a long time. Especially code written during a company’s early days, where you can practically feel how frantically the original developer was coding just by reading it.

A tiger leaves its hide when it dies; a developer leaves legacy code...

A tiger leaves its hide when it dies; a developer leaves legacy code...

Making reckless changes to such code can trigger a domino effect of unexpected breakages elsewhere. Developers who’ve experienced this a few times learn to approach legacy code modifications very carefully. In this situation, you roughly have four options:

- It’s too scary to touch, so just leave it alone.

- Somehow track down the person who left and ask them.

- Grab a nearby developer and ask them.

- Just analyze it yourself.

Option 1 has a low success rate unless you can talk the PO or CTO into it. And you probably won’t earn any points for it either. You’re getting paid as a developer, so you should earn your keep.

Messaging someone who’s already left the company to ask about their code intentions feels awkward at best. Option 3 is more reasonable, but your colleagues are busy too — you can’t keep pulling them aside every time. So ultimately, analyzing it yourself is the cleanest approach.

But analysis is easier said than done. In a large application, identifying every single dependency without missing anything is genuinely difficult. Moreover, this kind of analysis is often closely tied to business context, so it helps to also understand the business history behind the feature’s development.

If a teammate who knows the history is still around, great. But if not, the only thing you can rely on is the commit history — the record of what the original developer intended when they made each change.

Of course, developers rarely include business intent in commit messages when they’re coding under pressure. But if commits are made in meaningful units, you can at least figure out the developer’s intent behind each code change.

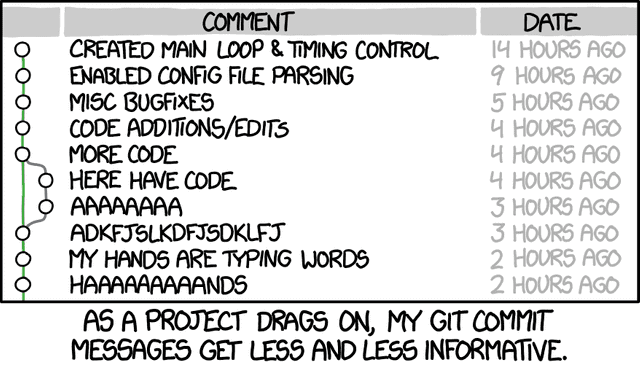

You’re literally reading history. But if the commit history is unnecessarily complex or the commit messages are a mess, reading it becomes a real struggle.

With commit messages like these, you can't tell what was changed.

With commit messages like these, you can't tell what was changed.[Source] https://xkcd.com/

This is why developers emphasize meaningful commit units, meaningful commit messages, and on top of that, using appropriate merge strategies to maintain a readable and meaningful commit history graph. What I want to explain here is how to create a clean history graph — and that starts with choosing the right branch merge strategy.

Three Merge Strategies for a Clean History

As I mentioned above, Merge, Squash and merge, and Rebase all merge two branches, but they differ in how they perform the merge and how they record commit history. Let’s look at how each strategy merges branches, how the commit history is recorded, and the pros and cons of each.

Create a merge commit

Merge is the standard merge strategy that most developers are familiar with. Its advantage is that even after a merged branch is deleted, it still appears as a separate branch in the history graph — so you can see “what commits happened on which branch and how they were merged.”

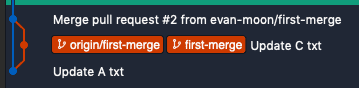

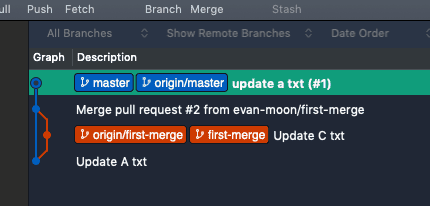

History showing first-merge branch merged into master

History showing first-merge branch merged into master

Even after deleting the first-merge branch, the history and branch lines remain

Even after deleting the first-merge branch, the history and branch lines remain

The downside is that the history is so detailed that as the number of branches and merges increases, the history graph becomes harder to read.

In principle, a commit should be the smallest meaningful unit of change, but in practice we often make trivial commits like fixing typos. These small commits don’t carry much information, and when they pile up, they actually hurt the readability of the history.

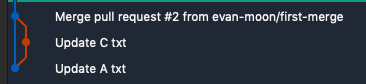

Larger applications tend to produce complex histories like this

Larger applications tend to produce complex histories like this

As shown above, merge commits that appear when a merge is performed provide valuable information about when and what was merged. But when many branches are being developed simultaneously, all these merge commits plus every commit from those branches get recorded, making the graph so complex that tracking history actually becomes harder.

The graph above shows an older history where the head has moved forward, so master is at the bottom as the latest version. Reading from master as the baseline, you can follow the flow reasonably well. But during active development when master’s head gets pushed back, it ends up somewhere in the middle of the graph rather than at the bottom — and tracking the history can become genuinely painful. (If you’ve tried this, you know your eyes start to hurt.)

Squash and merge

In Squash and merge, “squash” means combining multiple commits into one. This strategy takes all commits from the branch being merged, squashes them into a single commit, and commits it to the target branch. So the merge commit from Squash and merge isn’t really a merge commit in the traditional sense — it’s more like a single commit that bundles all changes from another branch.

The advantage is that since a merge commit is still created, you can tell at a glance from the history that a merge occurred and what changed in each version. Since the granular commits from the merged branch aren’t preserved, the record focuses purely on the fact that the merge happened — making it much easier to read through the program’s change history.

The disadvantage is less granular information compared to a regular merge commit. A regular merge shows who made which commits and which lines they changed, but Squash and merge consolidates everything into one commit, so that level of detail is lost.

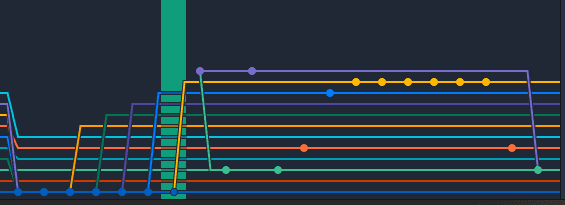

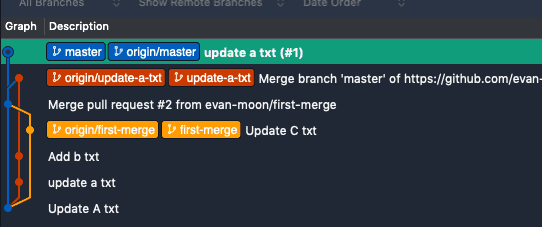

History graph before merging

History graph before merging

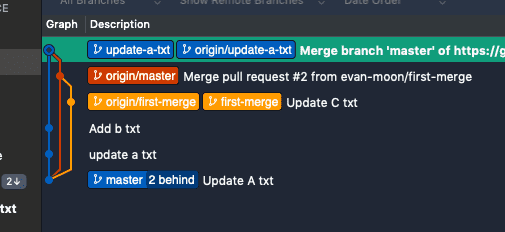

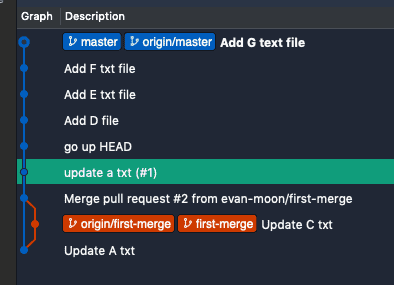

Here, the update-a-txt branch’s head is one commit ahead of master. Looking at the update-a-txt branch, it has two commits — update a txt and Add b txt — and has recently pulled in the latest changes from master. When we use Squash and merge to merge into master, all commits in this branch get combined into a single commit on master.

After merging update-a-txt into master using Squash and merge

After merging update-a-txt into master using Squash and merge

As you can see, unlike a regular merge, the update-a-txt branch line doesn’t flow into master. Instead, a new commit called update a txt(#1) is simply added to the master branch. This commit contains all the changes from the update-a-txt branch, combined into one.

After deleting the now-unnecessary update-a-txt branch, the squashed commit remains on master, but the detailed commit history from that branch is no longer visible. In other words, Squash and merge lets you see that a merge happened, but you can’t see the specific contexts in which individual code changes were made.

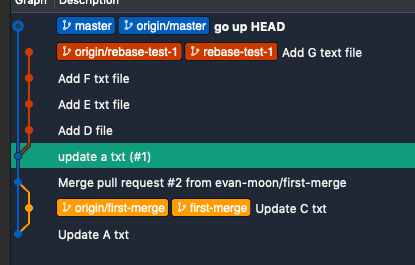

Rebase and merge

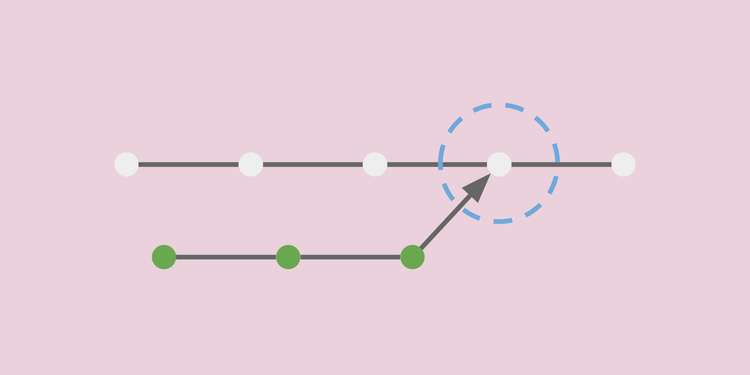

Rebase and merge uses Git’s rebase feature to merge branches. Rebase literally changes the base of a branch’s history. In simpler terms, it makes the changes from branch a look as if they were made on branch b.

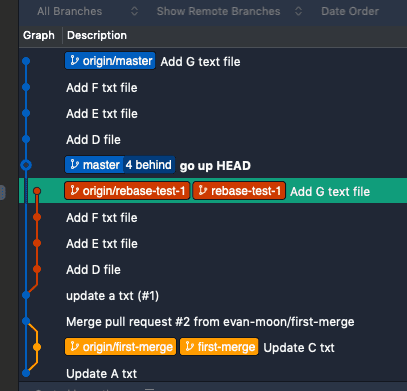

Rebase preserves all commits from the merged branch, so you retain full information about who changed what and when. However, you can’t tell at which point the branch was merged. That’s why when using rebase, you need to pay more attention to tagging than with other strategies.

The graph above shows the rebase-test-1 branch with 4 commits, ready to be merged into master. Using rebase to merge makes all changes from rebase-test-1 appear as if they were committed directly on master.

After the rebase, all commits from rebase-test-1 have been transplanted onto master. Deleting the now-unnecessary rebase-test-1 branch gives you a clean history graph that looks as if all development happened on master from the start.

As shown above, rebasing doesn’t create a merge commit, so there’s no way to tell when a branch was merged. That’s why I recommend using the tag feature to mark the point where the branch was merged. (Let’s use semantic versioning!)

One critical downside of rebase is what happens when a merge conflict occurs. Since rebase copies the branch’s history commit by commit onto the target branch, conflicts don’t happen once like with Merge commit or Squash and merge — they happen on each individual commit.

This might be manageable when the branch only has a few commits. But if you’re rebasing a large feature branch with hundreds of commits and conflicts start popping up, just accept your fate and go make some coffee.

Wrapping Up

Maintaining a clean commit history might benefit your future self, but it’s really more about being considerate to whoever will someday need to modify the code you’ve written.

As you can tell from reading through this, each of the three merge strategies has clear pros and cons — none is objectively superior. You simply choose the right one based on the situation or your team’s strategy. Some people argue that Squash and merge or Rebase are unnecessary and that regular merges are perfectly sufficient for version control.

Still, if you understand how these three strategies merge branches and how they record history, you can produce readable history graphs even in complex collaborative development scenarios. Clean history brings real benefits, so if you’ve only been using regular merges, I’d recommend experimenting with the other strategies.

That wraps up this post on keeping your commit history clean.