Object-Oriented Programming Is Actually Fun: A Quick Tour of OOP

Classes, inheritance, polymorphism — let's sort out the core concepts of OOP

In this post, I want to talk about Object-Oriented Programming — commonly known as OOP — one of the most widely used design methodologies in software.

OOP is a design paradigm based on the concept of modeling the real world in program design. It rose to prominence in the early 1990s and remains one of the most prevalent design approaches used by developers worldwide, so it’s well worth understanding.

Why Should I Learn OOP?

It’s true that OOP has enjoyed decades of popularity, but in recent years, critics have pointed out its shortcomings and paradigms like Functional Programming have gained significant traction. (FP is actually quite old itself.) At the end of the day, OOP and FP are both approaches to the question “How should I design my program?” — each with its own strengths and weaknesses. It’s only natural for improved paradigms to emerge over time.

Personally, I still think OOP is a solid design paradigm. But you might find Functional Programming more efficient and appealing — and that’s completely fine.

Choosing which paradigm you prefer is a matter of personal freedom. But making good choices requires understanding the trade-offs — what you gain and what you lose — which means even if you choose FP, you still need to understand what OOP is.

Moreover, OOP has played a crucial role in modern program design from the early 1990s through today. No matter how much attention newer paradigms receive, the fact remains that OOP underpins the design of most programs out there — and that’s one very practical reason to learn it, whether you love it or not. (Major languages like Java, Python, and C++ all support OOP.)

So in this post, let’s take a quick look at what OOP aims to achieve and what concepts make it tick.

What Does “Object-Oriented” Mean?

If you translate “Object-Oriented” literally, you get something like “directed toward objects.” The “objects” here refer to independent entities that exist in the real world. This is usually the very first concept you encounter when learning OOP. It’s actually quite simple once you understand it, but since it’s not something we consciously think about in daily life, it can feel confusing at first.

To explain objects, we need to introduce the concept of classes as well. The terminology isn’t the most intuitive, but the underlying idea is something anyone can grasp. Most tutorials use the cookie-cutter-and-cookie analogy, but instead of starting with “a class is X, an object is Y,” I’d rather begin with OOP’s broader design concept and let things fall into place naturally.

Let’s set aside the dry terminology for now and just follow along with an example.

Classes and Objects

At the top of this post, I said OOP is about reflecting the real world in program design. Once you understand what that means, concepts like classes and objects will click naturally. So let’s first explore why OOP is called a design approach that mirrors reality.

There are plenty of examples we could use, but everyday objects tend to resonate best. I’ll use smartphones as my example. Since I use an iPhone 7 made by Apple, let’s start there.

If we wanted to model the iPhone 7 as a program, we’d first need to define what an iPhone 7 actually is. Don’t overthink it — we’re not writing real code, so a rough definition is perfectly fine.

Off the top of my head: the iPhone 7 has a rounded body, a home button with a built-in haptic engine, and was the first iPhone to drop the 3.5mm headphone jack. (Personally, I wish they’d bring the headphone jack back…)

We can go a step further and define the higher-level concept of iPhone itself. After all, the iPhone 7 is just an extension of the broader iPhone concept.

So what is an iPhone? It’s a smartphone series manufactured by Apple that runs iOS. The concept of “iPhone” encompasses not just the iPhone 7 but also the iPhone X, iPhone 8, iPhone SE, and many other models.

Think about it this way: when you ask a friend “What phone do you use?” and they answer “iPhone” or “Galaxy,” they’re unconsciously grouping all the sub-models under a broader concept. That’s how natural and intuitive this kind of thinking already is. Don’t make it harder than it needs to be.

iPhone, as a higher-level concept, encompasses all iPhone series models.

iPhone, as a higher-level concept, encompasses all iPhone series models.

The key point: the lower-level concept (iPhone 7) has all the characteristics of the higher-level concept (iPhone). Similarly, other sub-concepts like iPhone X or iPhone SE also carry all of iPhone’s traits. Let’s push this one level further.

What’s the higher-level concept above iPhone? An iPhone is a smartphone made by Apple that runs iOS — so iPhone’s parent concept is smartphone. The smartphone concept encompasses not just iPhones but also Galaxy, Xiaomi, and other brands. And just as before, all these sub-concepts inherit the characteristics of “smartphone” while adding their own unique traits.

The concept of "smartphone" encompasses iPhones, Galaxy devices, Xiaomi, and all other smartphones.

The concept of "smartphone" encompasses iPhones, Galaxy devices, Xiaomi, and all other smartphones.

We can keep tracing upward from iPhone 7:

iPhone 7 → iPhone → Smartphone → Mobile Phone → Wireless Phone → Telephone → Communication Device → Machine…

This process of tracing and designing higher-level concepts is the foundation of OOP. The concepts like iPhone 7 and iPhone are what we call classes.

And the act of creating these higher-level concepts? That’s called abstraction. I’ll explain abstraction in more detail shortly — for now, just remember the concept of classes.

So what’s an object? Notice how many times I used the word “concept” when explaining classes. That’s exactly what a class is — it represents a concept. But a concept alone can’t become a tangible thing in reality.

Think about it: “iPhone 7” is just the name of a product line. It’s not a specific, unique physical item. By “unique,” I mean unique at the level of “only one exists in the entire world.” My iPhone 7 and your iPhone 7 are actually different iPhone 7s, aren’t they?

In other words, the iPhone 7 class has no tangible existence on its own. The class defines specs like CPU, display resolution, and memory. A factory uses these specs to produce an actual iPhone 7, assigns it a serial number, and ships it. Only then do we have a physical iPhone 7 we can hold in our hands.

That produced iPhone 7 has a unique serial number, so we know there’s only one iPhone 7 in the world with serial number 1234.

These produced iPhone 7s are what we call objects.

In short, a class is a blueprint, and you need to use it to create an actual, usable thing. An object is the real thing created from a class.

This OOP design approach lets us abstract most concepts from our daily lives. It’s actually fun to practice abstracting everything you see around you. A few examples:

- Sonata → Midsize Sedan → Sedan → Car → Vehicle

- Evan Moon → Male → Human → Primate → Mammal → Animal

- Overwatch → FPS Game → Game → Software

Almost every concept in our daily lives can be organized through this kind of abstraction. Practicing this with everyday objects is a great exercise you can do anytime — once you get the hang of it, you can sit in a café drinking coffee and mentally model the entire café as a program.

Ultimately, “object-oriented” means starting from the ability to represent everything in the real world by defining abstract concepts as classes and creating usable objects from those classes.

Let’s Think About Abstraction More Deeply

We just walked through a simple abstraction exercise starting from iPhone 7 and working upward. But you probably didn’t have to think very hard, because concepts like iPhone and smartphone are already deeply familiar. They were already somewhat abstracted and organized in your mind.

In real program design, however, you often need to define the concepts from scratch — they’re not always familiar everyday things. If you don’t precisely understand what abstraction is, you risk designing classes in strange directions. So let’s nail this down.

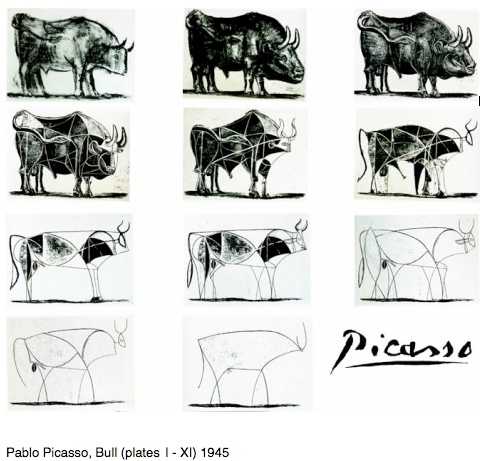

Let’s start with the word “abstraction” itself. Abstraction means identifying and capturing specific attributes from the many attributes an entity possesses. Looking at how Picasso progressively abstracted a bull in his famous series of lithographs gives a nice visual of what abstraction is:

Picasso's progressive abstraction of a bull

Picasso's progressive abstraction of a bull

Abstraction is about identifying the most characteristic attributes of something.

When we derived “iPhone” from “iPhone 7,” the process felt quite intuitive. But if you always approach abstraction that intuitively, it actually becomes harder to stay on track. The proper approach is to look at all the iPhone models and identify their common traits first, then use those to create the parent concept. The attributes of a properly abstracted parent concept will be universally applicable to all its children.

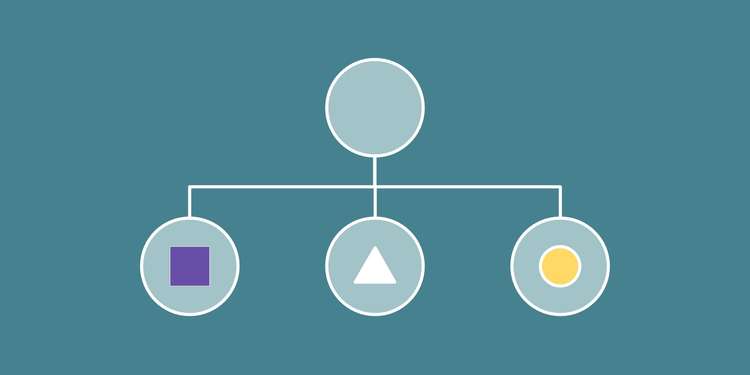

Parent concept

iPhone: An iOS-based smartphone made by Apple

Child concepts based on the iPhone class

iPhone X: An iOS-based smartphone made by Apple, with no home button and a bezel-less design.

iPhone 7: An iOS-based smartphone made by Apple, with a home button featuring a built-in haptic engine.

iPhone SE: An iOS-based smartphone made by Apple, compact enough to hold comfortably in one hand.

As this example shows, child concepts inherit all the attributes of the parent concept — which is why this process is called inheritance. I’ll cover inheritance in more detail below.

The Big Three of OOP

The concepts of classes, objects, and abstraction that we just covered are the foundations of OOP. Now I want to go a step further and explain a few more concepts that OOP-supporting languages provide. OOP programs are designed by assembling classes and objects, and these additional concepts exist to make that assembly smoother.

Some of these concepts aren’t implemented in JavaScript, so I’ll use Java for the examples. The syntax differences are minor enough at a glance that JavaScript developers should have no trouble following along. TypeScript does support OOP as well, but setting it up is more hassle than just compiling Java, so Java it is.

Let’s take a quick look at the “Big Three” of OOP: inheritance, encapsulation, and polymorphism.

Inheritance

Inheritance is the concept I briefly touched on when explaining abstraction. In many OOP languages, inheritance is expressed with the extends keyword. From the child’s perspective, it’s inheriting the parent’s attributes; from the parent’s perspective, its attributes are being extended into the child — hence extends. Let’s see how it works in code.

class IPhone {

String manufacturer = "apple";

String os = "iOS";

}

class IPhone7 extends IPhone {

int version = 7;

}

class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

IPhone7 myIPhone7 = new IPhone7();

System.out.println(myIPhone7.manufacturer);

System.out.println(myIPhone7.os);

System.out.println(myIPhone7.version);

}

}apple

iOS

7When creating the IPhone7 class, we used extends to inherit from IPhone. Even though IPhone7 doesn’t explicitly declare manufacturer or os, it inherits those attributes from its parent class IPhone.

Similarly, if we need to create an IPhoneX class, we can reuse the IPhone class directly:

class IPhoneX extends IPhone {

int version = 10;

}In other words, if you’ve built a well-abstracted class, you can reuse it whenever you need another class with similar attributes. And if a change applies across the entire iPhone series, you only need to modify the IPhone class — all child classes inherit the change automatically. This shortens development time and reduces the chance of human error.

But what if requirements change and you now need to model the Galaxy series? Galaxy phones use Android instead of iOS and are made by Samsung, not Apple — so we can’t reuse the IPhone class. We could just create a separate Galaxy class, but we could also go one level higher and create a SmartPhone class:

class SmartPhone {

SmartPhone (String manufacturer, String os) {

this.manufacturer = manufacturer;

this.os = os;

}

}

class IPhone extends SmartPhone {

IPhone () {

super("apple", "iOS");

}

}

class Galaxy extends SmartPhone {

Galaxy () {

super("samsung", "android");

}

}

class IPhone7 extends IPhone {

int version = 7;

}

class GalaxyS10 extends Galaxy {

String version = "s10";

}The super method calls the parent class’s constructor. Parent classes are also called “super classes” and child classes “sub classes” — hence the super keyword.

Child classes like IPhone7 or GalaxyS10 can also override the parent’s manufacturer or os attributes — this is called overriding. If you’ve done Android development, you’ve seen the @Override decorator constantly — it’s the same mechanism.

This class dependency structure improves class reusability, but if inheritance hierarchies become too complex, they become difficult to understand. It’s important to design inheritance with clear intent and reasonable depth. (Though what counts as “reasonable” varies from developer to developer — that’s the catch.)

Encapsulation

Encapsulation means hiding a class’s internal workings so that users of the class only need to know how to use it, not how it works inside.

By encapsulating a class, consumers don’t need to puzzle over internal logic. You can also hide internal variables and methods as needed, preventing unnecessary exposure and improving security.

Hiding a class’s internal data is called information hiding, typically achieved through access modifiers like public, private, and protected.

// Capsulation.java

class Person {

public String name;

private int age;

protected String address;

public Person (String name, int age, String address) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.address = address;

}

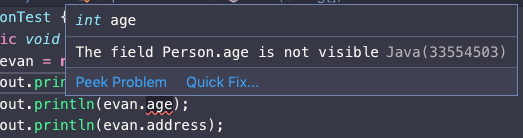

}Here’s a simple class. Person assigns constructor arguments to its member variables, each with a different access modifier: public, private, and protected.

Let’s create an object and see which members we can access:

// Capsulation.java

class CapsulationTest {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Person evan = new Person("Evan", 29, "Seoul");

System.out.println(evan.name);

System.out.println(evan.age);

System.out.println(evan.address);

}

}If you’ve typed this out, you already know: since Java is a compiled language, the IDE will have analyzed everything and drawn red squiggles before you even run it.

The error is on age — the member variable declared with the private access modifier. Variables and methods declared private can only be used within the class itself and are completely hidden from the outside. The public member name and protected member address are accessible.

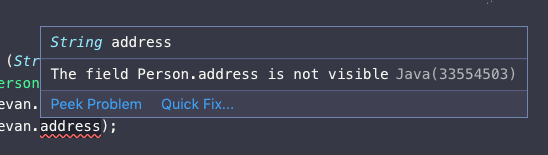

public clearly allows unrestricted external access, but protected being accessible might seem odd. You’d expect it to behave like private — so why is external access allowed?

The protected modifier blocks access from everything except subclasses and classes in the same package. In this example, Person and CapsulationTest are declared in the same file, so they’re in the same package — hence the access works.

What happens if we separate Person into a different package? Let’s create a MyPacks directory and move Person.java there:

// MyPacks/Person.java

package MyPacks;

public class Person {

public String name;

private int age;

protected String address;

public Person (String name, int age, String address) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.address = address;

}

}// Capsulation.java

import MyPacks.Person;

class CapsulationTest {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Person evan = new Person("Evan", 29, "Seoul");

System.out.println(evan.name);

System.out.println(evan.address);

}

}Now evan.address also gets the red squiggle treatment.

A protected member from an external package can’t be accessed directly. However, if you inherit the Person class, the child class can access protected members regardless of package:

// Capsulation.java

import MyPacks.Person;

class CapsulationTest {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Evan evan = new Evan();

}

}

class Evan extends Person {

Evan () {

super("Evan", 29, "Seoul");

System.out.println(this.address);

System.out.println(super.address);

}

}Seoul

SeoulAccess modifiers exist not only in Java but also in TypeScript, Ruby, C++, and many other OOP languages. Understanding them well lets you expose only the information you want, hide what you don’t, and save class consumers from unnecessary headaches.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism means that a single variable name or method name can be interpreted differently depending on the context. Since polymorphism is a concept rather than a single feature, it can be expressed in multiple ways.

Java’s key tools for polymorphism are abstract classes, interfaces, and overloading.

Abstract classes and interfaces serve somewhat different purposes, but the difference is hard to appreciate in a simple example — and since this is an OOP post, not a Java post, I’ll stick to abstract classes.

Let’s explore how these features work and develop a deeper understanding of polymorphism. Even if you’ve never heard the term, you may have been using this design pattern without realizing it.

Polymorphism with Abstract Classes

Abstract classes are one of Java’s go-to features for achieving polymorphism. Explaining purely in words is boring, so let’s look at code. I like Overwatch, so I’ll use it as my example.

The beloved hero shooter

The beloved hero shooter

I’m going to model several Overwatch heroes as classes. All Overwatch heroes share one common feature: “When your ultimate gauge is full, press Q to activate your ultimate ability.”

But each hero has a different ultimate: Reinhardt slams his hammer to stun enemies, McCree locks onto multiple enemies for simultaneous headshots, and Mei throws a robot that freezes enemies in an area.

Without polymorphism, hero classes might look like this:

class Hero {

public String name;

Hero (String name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

class Reinhardt extends Hero {

Reinhardt () {

super("reinhardt");

}

public void attackHammer () {

System.out.println("Hammer down!");

}

}

class McCree extends Hero {

McCree () {

super("mccree");

}

public void attackGun () {

System.out.println("It's high noon. Bang bang.");

}

}

class Mei extends Hero {

Mei () {

super("mei");

}

public void throwRobot () {

System.out.println("Freeze! Don't move!");

}

}If we want to activate each hero’s ultimate, what happens? Predictably, a miserable cascade of if or switch statements:

Since every hero’s ultimate method has a different name, there’s no alternative. And because Hero itself has no ultimate method, we also need to cast each object to its specific hero class — an annoying extra step.

class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Mei myMei = new Mei();

Reinhardt myReinhardt = new Reinhardt();

McCree myMcCree = new McCree();

Main.doUltimate(myMei);

Main.doUltimate(myReinhardt);

Main.doUltimate(myMcCree);

}

public static void doUltimate (Hero hero) {

if (hero instanceof Reinhardt) {

Reinhardt myHero = (Reinhardt)hero;

myHero.attackHammer();

}

else if (hero instanceof McCree) {

McCree myHero = (McCree)hero;

myHero.attackGun();

}

else if (hero instanceof Mei) {

Mei myHero = (Mei)hero;

myHero.throwRobot();

}

}

}Freeze! Don't move!

Hammer down!

It's high noon. Bang bang.Adding more heroes means more branches, and the sight of Mei myHero = (Mei)hero is enough to make your heart sink. Polymorphism is the concept that rescues us from exactly this kind of situation.

Remember: I defined polymorphism as “a single variable or method name being interpreted differently depending on the context.” So if we unify all hero ultimate methods under the name ultimate but have each hero execute different code when it’s called — that’s polymorphism.

We could manually add an ultimate method to each hero class that extends Hero, but that leaves room for developer error. (Typos being the most common offender.) So Java provides features that force developers to implement certain methods.

Those features are abstract classes and interfaces. As I mentioned, I’ll only use abstract classes here.

For the curious: in brief, abstract classes are for extending an existing class’s functionality, while interfaces define a pure contract with no implementation. Interfaces can’t contain method implementations, but abstract classes can. (Since Java 8, interfaces can have default methods with implementations — blurring the distinction further.)

Our Hero class receives a name from the constructor and stores it — so an abstract class is the better fit. Let’s use it to enforce the ultimate method:

abstract class Hero {

public String name;

Hero (String name) {

this.name = name;

}

// Declare an abstract method with no implementation

public abstract void ultimate ();

}

class Reinhardt extends Hero {

Reinhardt () {

super("reinhardt");

}

public void ultimate () {

System.out.println("Hammer down!");

}

}

class McCree extends Hero {

McCree () {

super("mccree");

}

public void ultimate () {

System.out.println("It's high noon. Bang bang.");

}

}

class Mei extends Hero {

Mei () {

super("mei");

}

public void ultimate () {

System.out.println("Freeze! Don't move!");

}

}Every hero class extending the abstract Hero is now required to implement the ultimate method. With unified method names, the consumer no longer has to guess which method to call:

class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Mei myMei = new Mei();

Reinhardt myReinhardt = new Reinhardt();

McCree myMcCree = new McCree();

Main.doUltimate(myMei);

Main.doUltimate(myReinhardt);

Main.doUltimate(myMcCree);

}

public static void doUltimate (Hero hero) {

// Any class extending Hero is guaranteed

// to have the ultimate method.

hero.ultimate();

}

}See how much simpler the code is? Since the abstract method enforces the presence of ultimate, there’s zero chance a hero class extending Hero lacks that method. Consumers can call ultimate with complete confidence.

And even though every hero class has a method named ultimate, the internal implementations are all different — so each hero activates a different skill. That’s polymorphism.

Polymorphism with Overloading

Now let’s look at an example of polymorphism through overloading. Don’t confuse this with overriding, which I mentioned briefly in the inheritance section.

Overriding replaces a parent class’s member variable or method. Overloading lets you use the same method name for different behaviors depending on the arguments — it’s a polymorphism feature. (I used to mix these up on exams all the time.)

Overloading is a straightforward concept, but it can be surprising for developers who primarily use languages like JavaScript or Python that don’t support it. The reason: overloading means “calling a completely different method based on what arguments you pass — even though the method name is identical.”

Wait, what?

Wait, what?

Imagine a class with a sum method that takes two arguments and returns their sum. What if you want to add three values? In JavaScript, which doesn’t support overloading, you’d have to use a workaround:

class Calculator {

sum (...args) {

return args.reduce((prev, current) => prev + current);

}

}

const c = new Calculator();

c.sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5);15Sure, it works — but this is just a JavaScript language trick, not true polymorphism. This approach turns “a method that adds two arguments” into “a method that adds n arguments,” but it can’t change the fundamental behavior of the method. True polymorphism requires the ability to change the operation itself, not just the argument count.

Java and C++, on the other hand, support proper overloading:

class Overloading {

public int sum (int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

public int sum (int a, int b, int c) {

return a + b + c;

}

public String sum (String a, String b) {

return a + b + " it is.";

}

}We’ve declared multiple sum methods with the same name. In JavaScript, the first two would be silently overwritten by the last one — no overloading possible.

The String version of sum even appends " it is." — a nice touch. In JavaScript, you’d need explicit type-checking conditionals to achieve this, but Java’s overloading handles it natively.

Let’s test these methods:

class Main {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Overloading o = new Overloading();

System.out.println(o.sum(1, 2));

System.out.println(o.sum(1, 2, 3));

System.out.println(o.sum("Ja", "va"));

}

}3

6

Java it is.The Overloading class has multiple sum methods, and depending on the arguments, a different method with the same name gets called. That’s overloading — one of Java’s key polymorphism features. (Don’t mix it up with overriding!)

Wrapping Up

The target audience I had in mind when writing this post wasn’t CS majors. If you studied computer science — or even took a CS elective — you’ve almost certainly encountered OOP in a university course.

The audience I’m writing for is people who recently learned to code at a bootcamp or similar program. From what I’ve seen, unless the curriculum is Java-based, bootcamps rarely cover OOP in any meaningful way.

It’s understandable — bootcamps aim to get students job-ready in a short time, which means prioritizing practical skills. But OOP isn’t a Java-only concept; it’s a universal programming paradigm applicable to any language, so it’s a shame when it gets skipped.

To be clear: I’m not saying “OOP is great, therefore you must learn it.” As I mentioned at the top, the world’s most popular languages — Java, Python, C++ — are either designed around OOP or fully support it. If you’re writing code today, you need to understand OOP whether you personally love it or not.

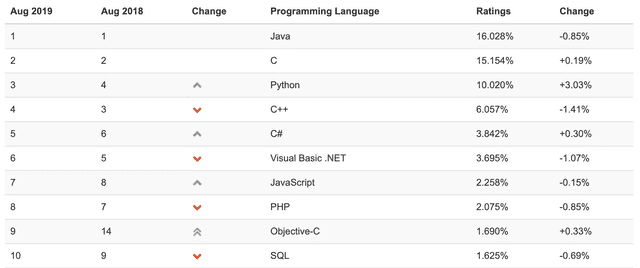

TIOBE language rankings, August 2019

TIOBE language rankings, August 2019Every language in the top ranks except C, JavaScript, and SQL uses OOP.

There’s no single right answer among programming paradigms. Just as you can’t easily answer whether declarative or imperative programming is “better,” the answer depends on context. We simply learn what each paradigm pursues, understand the concepts that emerge from it, and apply the right one for each situation.

In any case, I hope this post helps those who were unfamiliar with OOP — or found it intimidating — see it in a more approachable light.

That’s all for this quick tour of Object-Oriented Programming.