Basic Git for Newbies - Getting Started

For those who find Git difficult, the easiest first step

In this post I want to post about Git basics that you use, I use, and we all use. I first encountered Git in college and remember initially understanding it as just “uploading source code to some weird cloud.” But Git’s functionality doesn’t stop at simply code sharing - it’s a version management tool, so using Git well lets you flexibly handle dynamic situations unfolding at work.

But covering all Git features in this post would take too much space, so this time I’ll only explain basic commands for using Git: add, commit, push, pull, fetch.

Who Made Git and Why?

Git is a distributed version control system that Linus Torvalds made in 2005 for his own use. First, this Finnish guy Linus Torvalds is famous enough that most developers know him.

Those in the know will know, but this guy created the open-source kernel Linux. Famous operating systems made with the Linux kernel include Debian-based Ubuntu, Red Hat-based CentOS, etc. These operating systems are widely used on servers and have robust terminal basic features making them developer-friendly, so most developers know these operating systems. By the way, Android OS is also an operating system built on the Linux kernel.

Well anyway, this guy is quite famous in this industry - famous for programming well or creating the Linux kernel, but more famous for things like this:

The guts to flip off the world's #1 graphics card market share company

The guts to flip off the world's #1 graphics card market share company

This was around 2012, when he actually flipped off Nvidia like this during some forum speech. At the time there was an issue where OS made with Linux didn’t work properly on computers using Nvidia Optimus chips, and because Nvidia didn’t release open-source drivers citing intellectual property rights, installing Linux was difficult. The conversation then went roughly like this:

[Audience]

Uh dude… installing Linux on laptops with Nvidia Optimus chips is so hard ㅜㅜ Any good methods?[Linus]

…

I’m so happy to publicly point out that one of the worst problems we’ve had with hardware manufacturers has been Nvidia! This is a bit sad because Nvidia sells many chips in the Android market, but this company is truly the worst we’ve experienced.So Nvidia… go fuck yourself

That’s the kind of guy Linus is. By the way, if you carelessly commit to the Linux kernel just because it’s open source, this guy might curse you out and give you reality check, so brace yourself. This guy is this industry’s Gordon Ramsay.

But why did this guy make Git?

Linus used a distributed version control system called BitKeeper when making the Linux kernel, and this BitKeeper service was originally paid but provided free to the Linux community. But when one developer in this community reverse-engineered and hacked BitKeeper’s communication protocol, BitKeeper withdrew providing the service free to the Linux community.

But they didn’t block using it - just turned it from free to paid. But this guy didn’t want to pay money so he just made his own distributed version control system in 2 weeks! That’s Git. (2 weeks not 2 months…)

You can check Linus’s first commit to Git in Github’s Git mirror repository, where Linus’s personality also shows:

GIT - the stupid content tracker

“git” can mean anything, depending on your mood.

- random three-letter combination that is pronounceable, and not

actually used by any common UNIX command. The fact that it is a mispronounciation of “get” may or may not be relevant.

- stupid. contemptible and despicable. simple. Take your pick from the

dictionary of slang.

- “global information tracker”: you’re in a good mood, and it actually

works for you. Angels sing, and a light suddenly fills the room.

- “goddamn idiotic truckload of sh*t”: when it breaksLinus Torvalds git/git/README.md

Well, this is part of the README.md file from Linus’s first commit - Git is just a meaningless three-letter alphabet. He just decided it because there was no git command among Unix commands. When you’re in a good mood call it “global information tracker,” when in a bad mood call it “goddamn idiotic truckload of sh*t.” (Seriously not worldly cool.)

In summary, Git is a system that some Finnish genius guy made in 2 weeks because his version management tool suddenly became paid, and it’s now a widely used distributed version control system worldwide.

Understanding Basic Concepts

Since Git is a distributed version control system, modifying source on remote servers requires cloning the source to your local environment. Literally copying all source and receiving it to your computer.

After that, Git tracks files in your local environment and detects when you modify source. Then you select files or source code lines you want to reflect changes to the remote server and upload to the remote server.

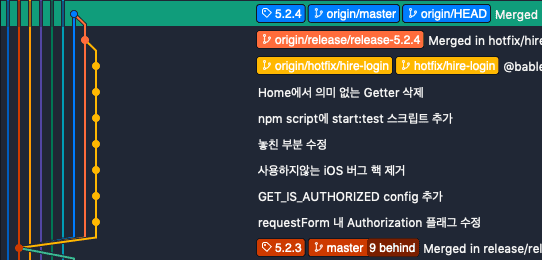

Top `origin/master` means remote server version, bottom `master` means my computer version.

Top `origin/master` means remote server version, bottom `master` means my computer version.

Okay, that’s the end of basic concepts about Git. Copy-paste files from remote server to my computer, modify them, then update back to remote server. Here, uploading your locally changed source to server source - in other words, pushing up to server - is called Push, and bringing server source to your client is called Pull or Fetch. Easy right?

But when first encountering Git, you might get confused because unfamiliar terms like remote, origin, repository pop up. So let’s simply understand what these terms mean first.

Remote / Origin

First, Remote literally means the remote server itself. If you don’t understand this remote server concept, think of using cloud storage we often use like Google Drive or N Drive. We’re storing our source on servers somewhere in the world.

Representative companies providing these servers are companies like Github, Bitbucket, GitLab. These companies didn’t create Git - they provide remote servers needed for the Git system and features making Git more convenient to use.

When using Git, you must decide which remote server to upload changes to, and since you don’t necessarily use just one remote server, you must name the remote servers you use. The conventional name mainly used here is Origin.

Usually most cases operate just one remote server, so many people use Remote and Origin interchangeably.

Repository

Repository (Repo) means storage, and you can think of it as project units distinguished within remote servers. Just like when using Google Drive we don’t throw all files into one directory but make several directories and divide files by purpose.

Generally one repository means one project, but depending on cases, one repository may contain multiple projects.

https://github.com/user/repository.git

https://user@bitbucket.org/group-name/repository.gitWhen cloning repositories, you need URLs pointing to those repositories, and repository names are expressed with .git extensions at the very end of URLs.

Branch

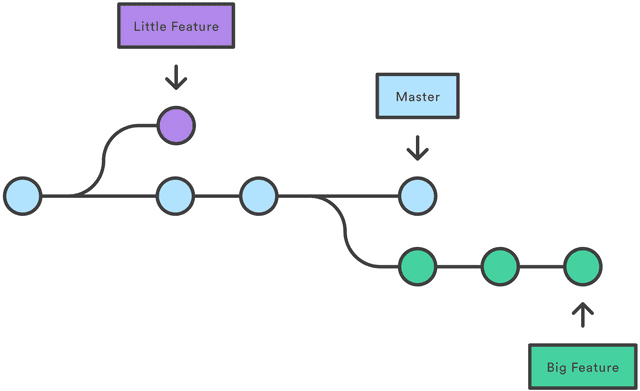

Branch is a workspace concept for proceeding with kind of independent work. When first initializing Git, a branch named master is created by default. Then you create new branches according to developing features or bug fixes, work there, then later merge back to master.

Separating other branches from master branch

Separating other branches from master branch

This branch concept might not be intuitively understandable for those unfamiliar with Git to briefly explain and pass, so I’ll explain again in another post later. For now let’s just remember these three points:

- Initializing Git basically creates a

masterbranch. This friend plays the main branch role.- Branches separate from some branch, and separated branches have the parent branch state as it was when separated.

- Developers proceed with development in each branch, then later merge changes back to the

masterbranch.

Let’s Learn Essential Commands

If you’re managing project versions alone, simply receiving source from remote server repository, changing it, then uploading back to remote server is actually no problem for proceeding with projects.

But since Git was made assuming collaboration situations where multiple people modify source together rather than solo development situations, it has many features to overcome various difficult situations that can arise in collaboration.

Git is basically used through CLI (Command Line Tools) and lets you use these features using various commands like commit, fetch, branch.

So this time let’s look at some commands you basically need to know to manage versions using Git.

Linking with Remote Server

clone

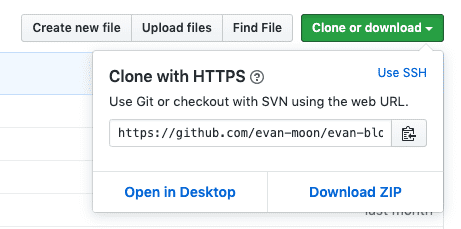

clone literally means copy-pasting files from remote server repository to client. Here, cloning requires information about which repository to get files from, and this information is expressed as URLs as explained above. You can clone source using HTTPS protocol or SSH protocol, usually using HTTPS.

Usually remote server providers like Github often make prominent buttons for easily cloning repositories and provide that repository’s URL. Users just need to copy that URL then use Git’s clone command to clone the repository.

$ cd ~/dev/evan # Move to desired working directory

$ git clone https://github.com/evan-moon/test-repo.gitAfter moving to your desired working directory and using the clone command to clone the repository, a directory with the same name as the repository is created at the current location and all remote server source is copied inside. In the above example case, a test-repo directory will be created inside the ~/dev/evan directory and that repository’s source will be copied.

Now even if you freely modify or destroy this copied source, as long as you don’t upload to the remote server, other people looking at the same remote server will absolutely not be affected, so feel safe to fiddle around.

pull

The pull command brings latest source from remote server and merges it into local source. Even if someone updated the remote server state after we first cloned source, the remote server doesn’t notify us of those changes, so we must directly query the server.

Also, pull isn’t simply the concept of “bringing from remote server to local” but rather “bringing and merging,” so branches can also merge source through pull.

$ git pull # Target is remote server branch with same name as my current local branch

$ git pull origin master # Target is origin remote server's master branchIf you’re interested in open source, you’ve probably heard the term Pull Request. This Pull Request means “take my working branch and merge it~”

I initially didn’t understand why it’s Pull Request not Merge Request, but thinking about it later, since the subject ultimately performing the act of merging two branches’ source isn’t the requester but the request receiver, from the perspective of the request receiver taking and merging the branch, I thought it seemed like appropriate naming.

fetch

fetch is a command that brings latest history from remote server to my client but doesn’t merge.

$ git fetchUsing the fetch command, you can receive all history that other people newly updated to the remote server. Now looking at that history, if my local version is an earlier version than the remote server version, just use the pull command to update my computer’s source code.

So you might think this command is a downgrade of pull, but pull and fetch have slightly different uses. pull is a bit dangerous because it immediately brings latest remote server source and merges into my local source without asking questions. For example, the remote server’s current latest source might be in a buggy state, right?

So I usually use fetch when I want to preview and compare changes between local and remote source. And using fetch well enables tricks like this:

#!/bin/bash

git fetch --all -p; git branch -vv | grep ": gone]" | awk '{ print $1 }' | xargs -n 1 git branch -dThis shell script is one I made before. After receiving latest content from remote server through fetch, it uses the branch command to find branches deleted on remote server but remaining locally and deletes them all. By the way, branches existing locally but deleted on remote have : gone text after the branch name so they’re distinguishable.

$ git branch -vv

* master fa0cec5 [origin/master] This is master branch

test 1f3578f [origin/test: gone] Branch dead on remote

test2 fa0cec5 Branch created locally and not updated to remoteUsing fetch command and branch command characteristics well lets you make such sweet scripts.

Updating Changes to Remote Server

Okay, so far we’ve looked at commands linking remote server content with local, now it’s time to look at commands uploading locally changed source to remote server. When explaining this process I usually give delivery examples, so in this post I’ll explain by comparing to packaging and delivering parcels.

add

add command selecting only desired changes

add command selecting only desired changes

Okay, think you did a used goods transaction on peaceful Joongongnara. Of course there might be generous people sending all items at home, but normal people wouldn’t, so before sending items to the other person we must first decide which items to send. Here the add command handles the process of selecting which items to package.

$ git add . # Stage all changes in current directory

$ git add ./src/components # Stage all changes in components directory

$ git add ./src/components/Test.vue # Stage only specific file changes

$ git add -p # Examine changes one by one while stagingHere selected changes move to a temporary space called Stage. Here the git add <path> command stages all changes inside that path, and if this feels unsafe, you can use the -p option to check changes one by one while staging.

Changes in stage like this can be checked using the git status command, and additionally using the -v option with the status command lets you see which parts of which files changed.

$ git add ./soruce

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: source/_drafts/git-tutorial.mdcommit

commit command packaging changes

commit command packaging changes

After using add to stage desired changes, now it’s time to package changes in stage. This packaging act is called commit. Committing is quite important in Git because Git defines one commit as one version. So naturally the criterion for “changing application to specific version” also becomes this commit.

$ git log --graph

* commit 20f1ea9 (HEAD -> master, origin/master, origin/HEAD)

| Author: Evan Moon <bboydart91@gmail.com>

|

| Finished signup feature development!

|

* commit ca693fd

| Author: Evan Moon <bboydart91@gmail.com>

|

| Add signup password input form

|

* commit f9b6e2d

| Author: Evan Moon <bboydart91@gmail.com>

|

| Add signup email input form

|In the above graph, what commit is my application’s current state?

Since HEAD is positioned at commit 20f1ea9 Finished signup feature development! on the graph, you can see my application’s current state has signup feature development completed.

And looking carefully at the graph, each commit has a unique hash value like 20f1ea9, and using this hash value you can freely move to any commit. For example, using the 회원가입 비밀번호 입력 폼 추가 commit’s hash value, you can move to the point when signup password input form was added with the git checkout ca693fd command. In other words, time travel is possible!

To properly utilize this commit feature, commits must be made in executable units. More simply, when changing versions to a specific commit, the application shouldn’t fail to execute properly and generate errors.

And as you can see in the above example, commits can contain messages. This message is the only means directly expressing what changes this commit caused, so pondering how to write good commit messages is essential. Fortunately many developers have already posted about how to write good commit messages, so Googling finds tons.

By the way, commit messages don’t necessarily have to be in English. Depending on organization there might be rules forcing commit messages written only in English, but actually commit messages are ultimately communication means, so just write them easily understandable for anyone anytime. So if you’re not comfortable with English, there’s no need to insist on English. Rather, if collaborating teammates aren’t comfortable with English, that can also be unnecessary communication cost.

Also, committing isn’t yet transmitting files to remote server but a process performed within user’s client, so committing changes has no issues even without internet connection. (Even coding on airplanes allows committing!)

Actually when I was a Git newbie this word commit was a bit confusing, because many developers use commit and push with the same meaning. But these two commands play distinctly different roles, so try distinguishing them.

push

push command delivering changes to remote server

push command delivering changes to remote server

Changes packaged through commit are uploaded to remote server using the push command. Since this actually transmits committed changes to the actual remote server, you must be connected to network. Conversely, you don’t need network connection until committing, so in environments with restricted internet like inside airplanes, you can proceed only until committing then push to remote server after arriving at destination.

And since there’s no rule that local branch A must only push to remote branch A, when pushing commits to remote server you must also tell Git “which branch of which remote server to push to.”

$ git push origin master # Push to origin remote server's master branch!But if the branch name is just master then typing the branch name each time is manageable, but something like feature/SD-0000-request-api-refactoring makes typing the branch name each time annoying.

So Git also provides features for automatically tracking branches.

$ git push --set-upstream origin masterUsing the --set-upstream option and entering the branch name just once at first, after that you can push changes to the initially entered branch automatically by just entering the git push command.

Like this we’ve looked at all processes of clone, add, commit, push - receiving source from remote server repository to my computer, changing files, then updating those changes back to remote server.

Wrapping Up

Actually explaining everything about Git in one blog post is difficult, so in the next post I want to post about commands actually used for managing versions like branch, checkout, merge, revert and their concepts.

Git is widely used in actual work but seems to get somewhat sidelined treatment at educational institutions like universities or academies. Well, actually universities teach more fundamental engineering not coding, and for academies teaching coding instead of version control systems is more advantageous for employment. (I hear nowadays instructors come to universities to lecture about Git.)

Anyway, using Git well lets you handle sad situations occurring when proceeding with projects, like needing to bring just one module another developer developed to my branch, or source getting deleted because commits got tangled, so you can become a developer loved by teammates.

That’s all for this post on basic Git for newbies - getting started.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Basic Git for Newbies - Version Management

Programming/TutorialLet's Keep Our Commit History Clean

Programming/TutorialCustomizing Jira Project Issues

Soft Skills/TutorialSimply Applying HTTP/2 with AWS

Programming/Network[Deep Learning Series] Understanding Backpropagation

Programming/Machine Learning