The Path from My Home to Google

Let's look inside the internet we use daily

In this post I want to briefly talk about what process our home goes through to communicate with Google. Among things I learned at university that I thought were interesting, one representative thing was the fact that all computers connected to the internet are actually connected through cables.

Some might think this fact obvious, but it seemed quite amazing back then. Though I use internet daily, it’s an element so naturally melted into life that I didn’t care much about its principles.

Then as I learned more detail about networks at school, I realized “these benefits I’m using matter-of-factly are actually a very systematic and complex system.”

So in this post I want to simply unpack that system through the process of accessing Google servers from my home. Of course, since I’m making rough estimates based on IP addresses, it won’t be exact information, but I’ll focus on roughly what processes enable accessing servers overseas.

IP, Internet Protocol

First, to know the path from my home to Google, let’s briefly learn about IP, inseparable from internet. The term IP address is a very familiar term even for non-computer majors.

In typical environments, you can think of this IP address playing our home address’s role when we access internet. Likewise, points along the path from my home to Google all have IP addresses, and we can roughly guess where these points are based on those IP addresses.

I’ll explain very basic content about IP, so those who already know can just skip.

IPv4 Structure

Generally the form we can encounter like 192.168.0.1 is IPv4. IPv4 consists of four fields composed of 8 bits, and each of these fields is called an octet. (By the way, terms starting with Oct often mean 8).

For example, 192.168.0.1 can be represented in binary like this:

Decimal: 192.168.0.1

Binary: 11000000.10101000.00000000.00000001Since one octet can only have 8 bits, octets have 00000000-11111111, i.e. 0-255 in decimal. So the number of addresses IPv4 can create is , about 4.3 billion. 4.3 billion… seems like quite a big number. When first making this address system, they probably thought:

Eh, 4.3 billion should last somewhat, right?

.

.

.

As worldwide internet users grew faster than expected, all addresses were ultimately exhausted as of February 4, 2011, and currently IPv4 allocation is stopped. Fortunately they weren’t just sitting idle during that time, and smart people worldwide already prepared countermeasures, so don’t worry too much.

IPv4 Classes

Like this, IP addresses aren’t resources you can just freely distribute but finite resources, so they manage by dividing usage by specific ranges. These divided ranges are called classes, managing by dividing into total 5 classes A-E.

Each class creates restrictions on the 8 bits in the first field of IPv4 expressed in binary 00000000.00000000.00000000.00000000, so just looking at the first field’s number, you can know which class that IPv4 address belongs to.

This restriction forces the first field’s most significant bits. For example, A class must always start with bit 0, so can use first fields between 00000000(0) and 01111111(127), and C class must always start with bits 110, so can use first fields from 11000000(192) to 11011111(223).

| Class | First Field | Address Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0xxxxxxx | 0.0.0.0 ~ 127.255.255.255 | Large-scale networks |

| B | 10xxxxxx | 128.0.0.0 ~ 191.255.255.255 | Medium-scale networks |

| C | 110xxxxx | 192.0.0.0 ~ 223.255.255.255 | Small-scale networks |

| D | 1110xxxx | 224.0.0.0 ~ 239.255.255.255 | Multicast |

| E | 1111xxxx | 240.0.0.0 ~ 255.255.255.255 | Reserved for research/development or future |

Special Purpose IPv4 Addresses

Like this, dividing classes and even within those classes, there are IPv4 addresses pre-reserved for special purposes. These reserved addresses are defined by RFC 5735 and cannot be allocated for purposes beyond their intended use. In this post I’ll briefly explain just some representative ones.

| Class | Address | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| A | 0.0.0.0 ~ 0.255.255.255 | Unallocated meta addresses |

| A | 10.0.0.0 ~ 10.255.255.255 | Large-scale private networks |

| A | 100.64.0.0 ~ 100.127.255.255 | Addresses for Carrier-grade NAT |

| A | 127.0.0.0 ~ 127.255.255.255 | Self. A.k.a. Loopback |

| C | 192.168.0.0 ~ 192.168.255.255 | Small-scale private networks. Often seen using routers. |

Let’s Look at the Path from My Home to Google

Okay, finally I can start this post’s main content.

Opening MacBook at home and entering google.com in web browser, the web browser will send a request to Google servers somewhere in the world to send pages. But my MacBook isn’t directly connected to Google servers.

So the request I sent goes through a rough journey, stopping here and there to reach Google servers. So now let’s find out where my request sent from home stops before reaching Google servers.

Using traceroute

Since I use Unix-based MacOS, I’ll explain based on MacOS. Using the traceroute utility, I can find out what path packets I sent take to reach Google servers.

$ traceroute -q 1 google.com

traceroute to google.com (172.217.25.196), 64 hops max, 52 byte packets

1 192.168.25.1 (192.168.25.1) 3.077 ms

2 211.0.0.0 (211.0.0.0) 5.928 ms

3 100.71.51.17 (100.71.51.17) 4.693 ms

4 10.44.255.240 (10.44.255.240) 4.328 ms

5 10.222.18.10 (10.222.18.10) 7.319 ms

6 10.222.16.201 (10.222.16.201) 4.883 ms

7 10.222.16.41 (10.222.16.41) 3.853 ms

8 72.14.204.124 (72.14.204.124) 34.784 ms

9 108.170.242.193 (108.170.242.193) 37.751 ms

10 108.170.233.79 (108.170.233.79) 36.643 ms

11 nrt13s50-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.25.68) 35.416 msThe second hop outputs public IP that could expose my detailed location, so I masked it for security. Actually the ISP (Internet Service Provider) I use, SK Broadband, has IP address lease period within managed areas of 1 hour, and I reside in a high population density area, so even if that IP address is exposed, location isn’t easy to know, but I’ll cover it because I’m still anxious.

What if someone finds my home...

What if someone finds my home...

One row output from traceroute results is called a hop, meaning the path my packets went through from my home to Google servers. The time output to the right of the hop’s IP address means the time the hop responded. Interestingly, from hop 8 the response time suddenly jumps from single digits to double digits - from here packets left the country and went overseas.

So what do these IP addresses mean?

Let’s Learn More Detail!

Now I want to learn more detail about what each of these IP addresses means, what company owns what device. A simple method is using the whois utility.

$ whois 172.217.25.68

NetRange: 172.217.0.0 - 172.217.255.255

CIDR: 172.217.0.0/16

NetName: GOOGLE

NetHandle: NET-172-217-0-0-1

Parent: NET172 (NET-172-0-0-0-0)

NetType: Direct AllocationMacOS’s whois utility sends requests to 5 whois services and outputs received results. By the way, South Korea’s whois service is provided at KISA’s (Korea Internet & Security Agency) Whois Search.

| whois Domain | Responsible Area |

|---|---|

| whois.arin.net | Americas |

| whois.nic.mil | USA (currently not working) |

| whois.ripe.net | Europe |

| whois.apnic.net | Asia Pacific |

| whois.jprs.jp | Japan |

However, whois service basically shows information about owners of IP addresses where domains are registered, so information about gateways or routers without registered domains doesn’t appear. So I’ll try searching using a site called IP2Location. (But this also doesn’t seem likely to show well)

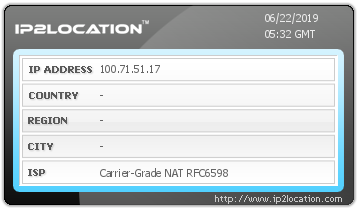

First, the first hop 192.168.25.* is private IP allocated by my home router, and the second hop is public IP the ISP gave me but masked for security, so let’s start examining from the third hop 100.71.51.17.

100.71.51.17

Ah, indeed not much information came out. Instead it output information that that IP address is used for Carrier Grade NAT. As explained above, A class 100.64.0.0 - 100.127.255.255 range being used for Carrier Grade NAT is already defined as standard, so it actually output an obvious result. So what is Carrier Grade NAT that my packets stopped by?

First, NAT is abbreviation for Network Address Translation, technology mainly for multiple hosts belonging to private networks to access internet using one public IP.

I’m using multiple SK Broadband services like IPTV and Wi-Fi. But giving separate IP addresses per subscribed service is very insufficient, so SK Broadband allocated me just one public IP address and installed a router with NAT function at home, building a Private Network at my home.

Carrier Grade NAT (CGN) can be thought of as NAT’s large-scale version. The router installed at my home only configures private network inside my home, but CGN is NAT configured on backbone network. Simply put, like a giant router…?

As I know, originally they operate CGN on backbone networks to manage wireless internet devices directly connected to mobile networks like smartphone LTE with NAT, but I don’t quite understand why my packets using home router are riding CGN. SK Broadband doesn’t have many IPv4… are they so lacking they attached CGN even to wired internet…? (If anyone knows, please tell me…I’m curious…)

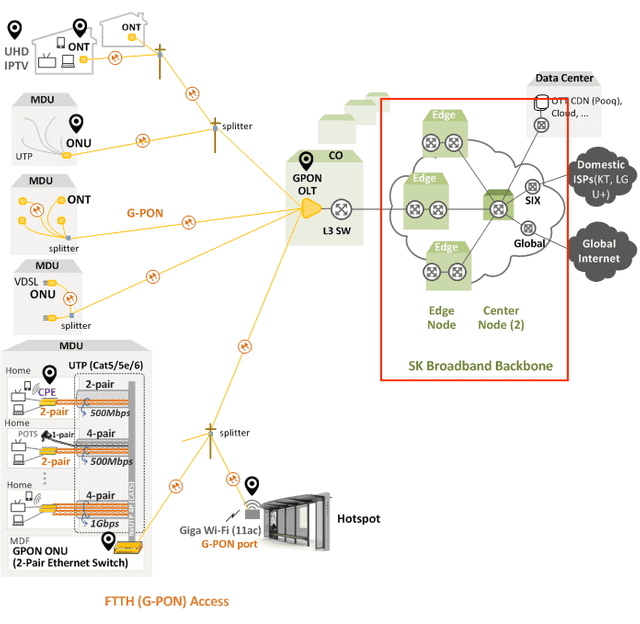

10.44.255.240 ~ 10.222.16.41

From here it’s IP allocated to A class private network, so guessing, it seems inside SK Broadband’s backbone network. Since ISPs don’t detail their network structure, I can’t know exactly where the node is located, but it seems roughly around here in SK Broadband’s network structure.

From here connects to other domestic ISPs or overseas networks

From here connects to other domestic ISPs or overseas networks

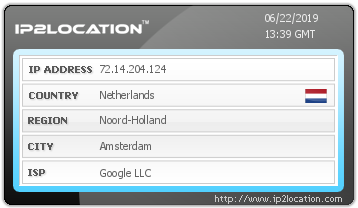

72.14.204.124 ~ 108.170.233.79

Finally devices Google owns appeared! But the location is Amsterdam, Netherlands. Google is a company in California, USA, but I don’t understand why Amsterdam suddenly appeared. Something seems strange, so I should ask whois.ripe.net, the whois service responsible for Europe.

whois -h whois.ripe.net 72.14.204.124

inetnum: 69.194.128.0 - 76.255.255.255

netname: NON-RIPE-NCC-MANAGED-ADDRESS-BLOCK

descr: IPv4 address block not managed by the RIPE NCCIndeed they say it’s not an address managed here. Then let’s ask whois.arin.net responsible for Americas.

whois -h whois.arin.net 72.14.204.124

NetRange: 72.14.192.0 - 72.14.255.255

CIDR: 72.14.192.0/18

NetName: GOOGLE

NetHandle: NET-72-14-192-0-1

Parent: NET72 (NET-72-0-0-0-0)

NetType: Direct Allocation

OriginAS:

Organization: Google LLC (GOGL)

RegDate: 2004-11-10

Updated: 2012-02-24

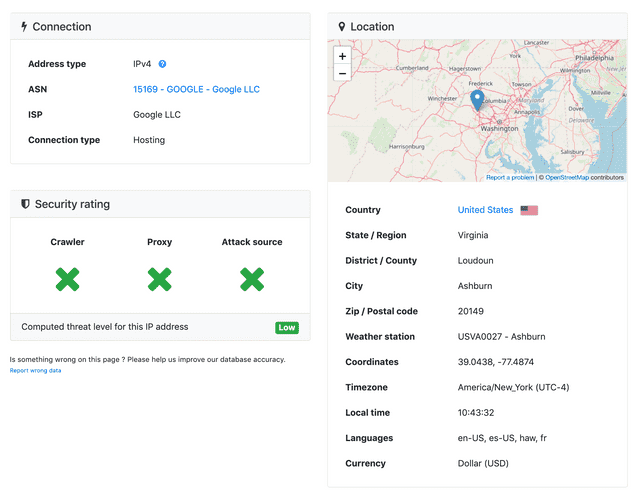

Ref: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/ip/72.14.192.0Oh, proper information came out this time. The device with address 72.14.204.124 seems to be something Google owns. Since IP2Location lost my trust now, I’ll ruthlessly discard it and use a new solution called DB IP.

Searching using DB IP, the location shows as Ashburn, Loudoun, Virginia, United States and Connection Type is Hosting.

After that, hop 9 108.170.242.193 and hop 10 108.170.233.79 also displayed as hosting servers located in Virginia. What on earth is there that they’re all gathered cozily here…?

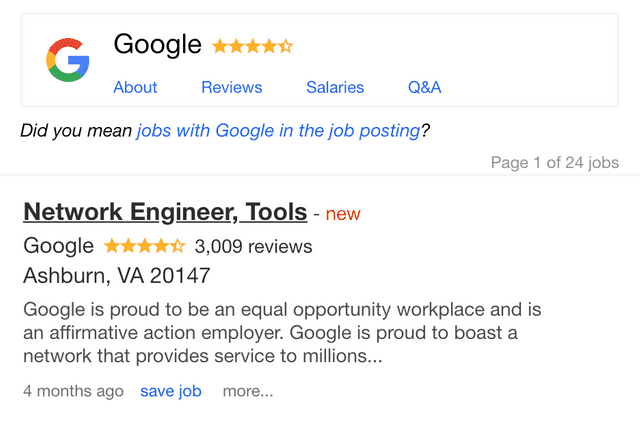

Googling a bit, I found announcements of Google hiring people to work in Ashburn. Also many job postings uploaded to neighboring towns Sterling and Reston in the same Virginia state.

Hire me...sob

Hire me...sob

Scanning the announcements, keywords like Network Engineer, Administrative Business Partner, Data Center, Google Cloud appear a lot, so it seems there’s a Google data center here. Searching more information, an article about Google doubling its Virginia workforce was also written in February this year.

It seems certain there’s a Google data center here.

172.217.25.68(google.com)

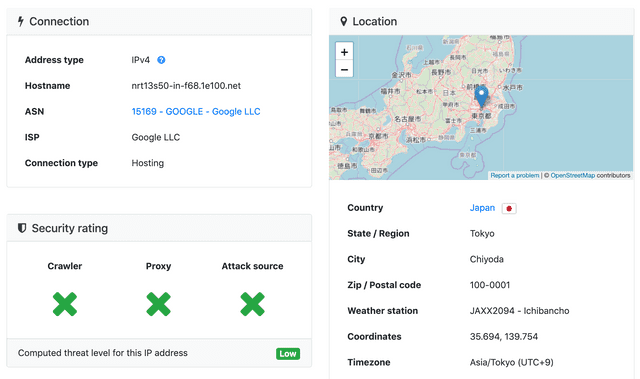

Okay, finally the server with address 172.217.25.68, the final destination of google.com domain. Searching this address through DB IP also says it’s a server in Japan.

Actually, it’s obviously much faster for me in Korea to receive information from servers in nearby Japan rather than continuously receiving information from servers in America. My packets were drawing a strange route crossing the Pacific to America then crossing again to Japan…

Digging deeper I could know why it draws such a route, but the post seems too long so I’ll dig only up to here. (Dig deeper next time…) Even Google I always accessed without thought, looking closely, gets delivered to me through such various paths. It’s a newly amazing fact.

That’s all for this post on the path from my home to Google.

관련 포스팅 보러가기

Why Did HTTP/3 Choose UDP?

Programming/NetworkWhy we need to know about CORS?

Programming/Network/WebSharing the Network Nicely: TCP's Congestion Control

Programming/NetworkTCP's Flow Control and Error Control

Programming/NetworkHow TCP Creates and Terminates Connections: The Handshake

Programming/Network